A beautiful and densely packed show, the Smart Museum’s exhibition not all realisms: photography, Africa, and the long 1960s deftly illustrates photography’s use in everyday African life from the mid-century to the present day. Through magazines, pamphlets, and other printed materials, alongside, art photography and contemporary collage, the show focuses on the post-colonial years in Ghana, Mali, and South Africa. The collection of works leads viewers through a timeline of essential dates, photographers, and movements to broadly illustrate the role of photography in disseminating information and provoking emotions.

The show consists of preserved cultural ephemera and artworks divided by temporary walls and perforated partitions. While there is some content overlap between the four thematic sections of the show, the exhibition guides viewers to separate the media visually and mentally. The element that connects everything is collage, an artistic style that is able to transcend any mode of communication. Anti-colonial parties use it to lay bare injustice, contemporary artists use it to blend the past and present, and international organizations use it to bring support to movements. These collages are a high point of the show that captures how an image moves from a camera roll to a newspaper to an art form.

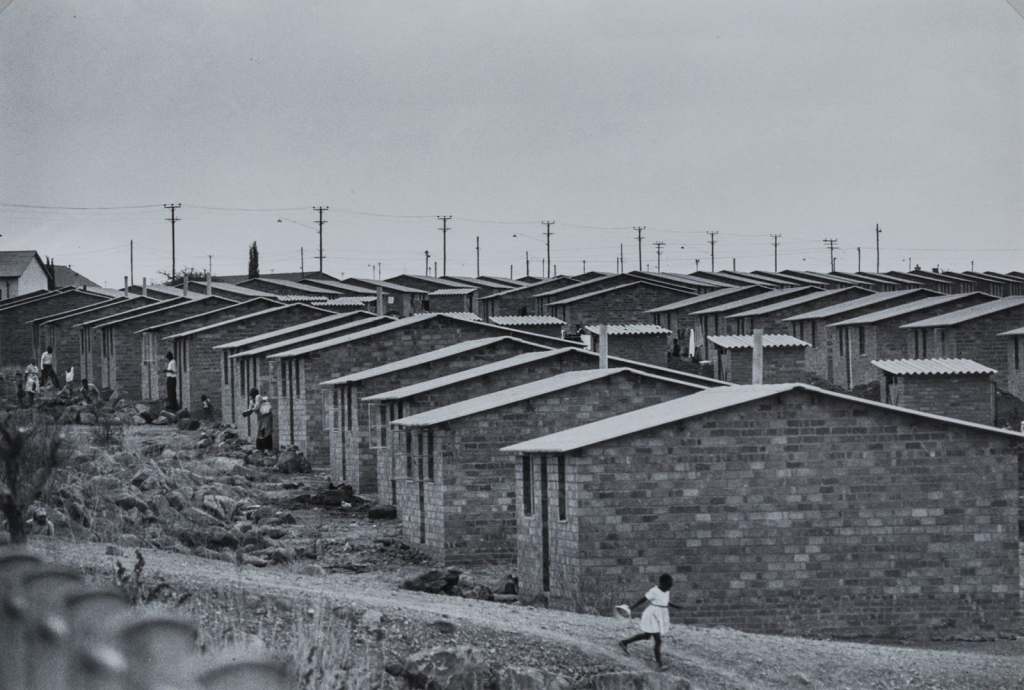

In the historical ephemera-driven sections, the curators touch on a variety of subjects and formats. By incorporating local media like the South African magazine Drum, photographs from and physical editions of Ernest Cole’s banned book House of Bondage, and many governmental and non-governmental pamphlets, show the illusion of political progress claimed on all sides. The show’s thesis comes to fruition in its display of photographs, perfectly matted and framed alongside their publication in printed materials. In particular, one section pairs Cole’s photographs with open copies of House of Bondage. This photo book from 1967 captured the state-sanctioned violence against Black South Africans during apartheid. Each image stands alone formally beautiful in shades of black and white as they capture everyday people and places. It is only when the images of people are put on the printed page that Cole’s captions address the subjects’ often harsh reality. These juxtapositions drag the photographs out of their fine art context and force viewers to confront inhumane conditions brought upon Black South Africans during apartheid that Cole paid careful attention to capture.

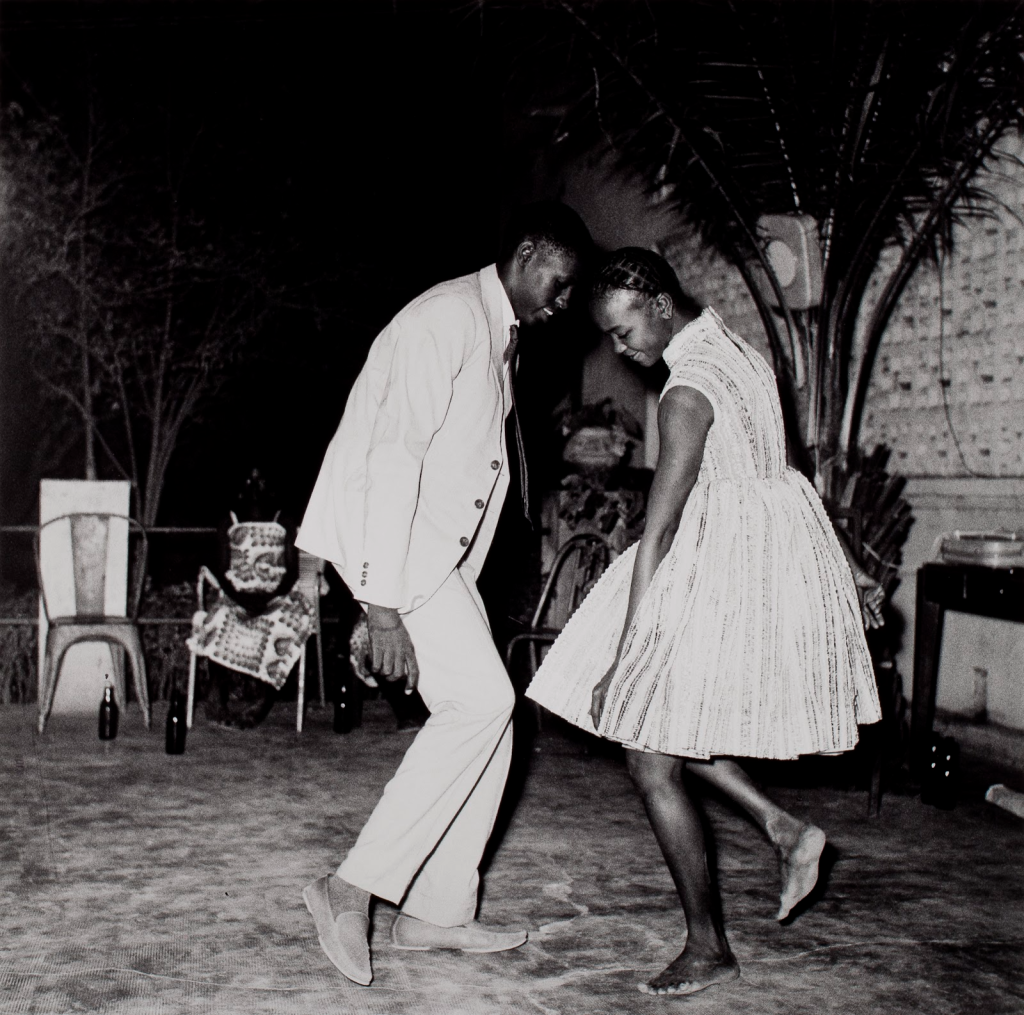

As a counterargument to Cole’s beautiful, yet tragic photographs, the show abruptly transitions to the joyful photography of Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé, photographers who went beyond simply capturing the likeness of their subjects. Their images also captured a moment in time with the fabrics, patterns, and poses of the 1950s and 1960s in Bamako, Mali. Keïta’s photos on view are inescapable with their layers of swirling, vegetal backdrops contrasting the striking vestments of his sitters. In one lovely image, Keïta turns the lens on himself; he brings the florals from background to foreground, while caressing flowers gently against his slight, soft smile, his eyes letting the viewer know he got the shot.

The show’s narrative approaches the 21st century with the inclusion of two contemporary artists, Njideka Akunyili Crosby and Sam Nhlengethwa. The Nigerian and South African artists, respectively, create massive collages that hang on walls opposite each other. Crosby’s multi-media work lifts inspiration from Malick Sidibé’s celebrated photograph Nuit de Noël (Happy Club), which the curators placed on display next to the piece. The brother and sister duo in Sidibé’s original image become at once larger than life and in color in Crosby’s collage. Their lockstep dancing time travels from 1963 to 2017, as the siblings dance next to Crosby and her husband who take center stage on the dance floor. Neatly tiled photographs arranged up and down, left and right comprise a good portion of the scene. Repurposing the transferred image from their previous lives as magazine covers, street photographs, and advertisements, they now live on as a dance floor, men’s suit, and even as photographs decorating a wall in painted frames. The scene has a palpable feeling of joy as lovers, friends, and family intertwine to the music. The unheard playlist includes the electro-funk sound of Nigerian musician William Onyeabor, whose song “When the Going is Smooth & Good” lends its name to the artwork. Crosby permanently entangles herself with dancers of the past, blurring lines of time and space to let loose on her fictional dance floor.

Inspired by Romare Bearden and Ernest Cole by Sam Nhlengethwa similarly uses pre-existing images of people, but he takes a radically different approach for his looming, 120 x 220 cm canvas. The setting is a cityscape that at first glance looks like a singular, blown-up photo with smaller figures and objects collaged together in the foreground. But upon further inspection, the mismatched layers of the city reveal themselves through the slightly skewed and leaning angles of skyscrapers and mismatched fields of depth. Nhlengethwa’s rather large collage elements create a busy background of steel and glass that seems to exist infinitely. The people populating the foreground are miniature in scale to the daunting infinitesimal cityscape behind them.

While Nhlengethwa’s style is messier and less precious than Crosby’s rectangular grid of collaged photos, they both take inspiration from artists also featured in the show. Nhlengethwa goes as far as naming his visual artist forebears in the title of his work. By alluding to inspiring artists in their titles, they honor the creatives who came before them and continue to inspire them. Their work is not possible without those who paved the way in previous decades. The generational conversations could fly back and forth forever, it is only a matter of time before we start to see artists referencing Nhlengethwa and Crosby by name.

By including contemporary and historical pieces in the show, the curators refuse to let the older photographs and ephemera languish in history and archives. The images and printed matter from the 1950s and 1960s take on a new life as they come alive in the 2010s through Crosby’s and Nhlengethwa’s interpretations, and again in the 2020s as the works find new context with one another in this show. Even if someone were to come just to see the beloved photographs by Malick Sidibé, it is impossible to leave without soaking in the historical contexts of his work and the photographers working alongside him.

not all realisms: photography, Africa, and the long 1960s is on view at The Smart Museum of Art from February 23 – June 4, 2023.

About the author: Elizabeth Upenieks is a Chicago-based curator, writer, and art historian. She earned a BA in Art History from the University of Texas and an MA in the History of Art & Architecture from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Her most recent projects include What We Do in the Shadows and PLATFORM 26: Myoung Ho Lee, Tree…#2 at deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, Lincoln, MA.