The Chicago Archives + Artists Project (CA+AP) is an initiative that pairs Chicago artists with archives and special collections to spark new experiments in creative interpretation, to showcase the rich histories and materials being preserved in participating archives, and to share archival practices with local artists and their communities. The project explores archives across the city via online features, a series of public programs and new commissioned artwork by Chicago artists. However, due to the ongoing pandemic, this current iteration of the project looks a little different. We have reimagined the project to take the shape of a book to be launched in Spring 2023: The Chicago Archives + Artist Project: Case Studies in Collaboration, which you can pre-order now! In the book, along with the wider history of the project, you’ll find the newly commissioned work of this year’s archive and artist pairing: Shorefront Legacy Center + Ben Blount, and the DePaul Art Museum + Natasha Mijares.

This series of articles profiles these featured archives and artists over the course of their collaboration, exploring the vital role of the archive in preserving and interpreting the stories of our city as well as the ways in which they can be a resource for creatives in the community.

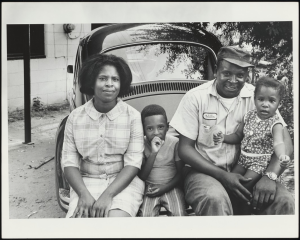

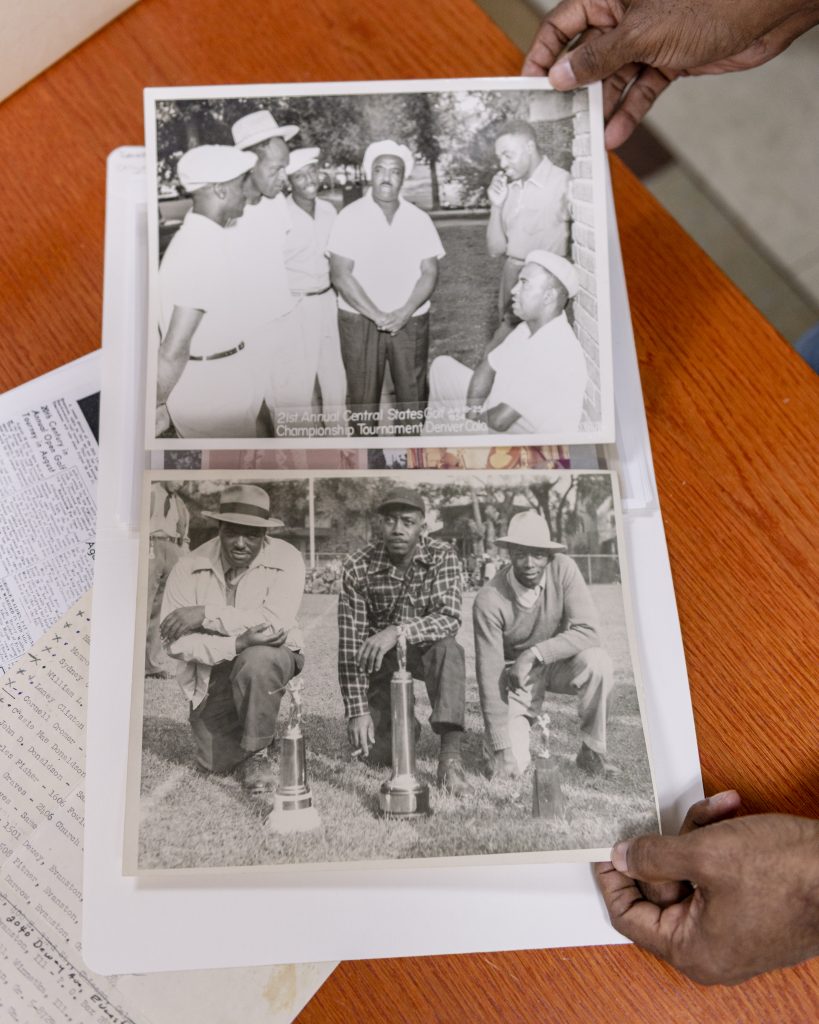

For this installment, we sat down with the founder and director of Shorefront Legacy Center, Dino Robinson. It has been his life’s mission to preserve and share the legacy of Black life on the North Shore and he has done so over the past two decades through Shorefront. The following interview has been edited.

Elizabeth Upenieks: In doing research on Shorefront Legacy Center, I saw that you were the main founder. As the main founder, what specific research brought you here and how have you built this amazing collection over time?

Dino Robinson: Shorefront was born out of a necessity [to fill a gap] that other local historical organizations were not [covering]. In the mid-90s I was doing my own family history that had nothing to do with Evanston or the North Shore. I was doing genealogy work that was handed over to me by my grandmother who was the family historian. I credit her for really getting me interested in doing genealogy work on families. Shorefront grew by wondering what our local history was like on the North Shore and not seeing much information. What I saw was that Blacks were in the North Shore; we were domestics and we went to church. That was a narrative that I witnessed growing up in this community. I thought it was imperative that members of the community control their narrative and share and archive their own stories so they were not written out of public history. I wasn’t sure what it was going to look like at the time. I think for me it [started as] a self-interest [project] and then as I talked to other people, they were interested, so we kind of formed a little group and started talking and researching together. Next thing you know we’re doing these projects and discussions. We became a nonprofit and have grown since then.

EU: That’s really amazing. I love when you have that personal tie. It just makes it so much more important and the passion and drive behind it fuels so much there. I saw a recent story about how Shorefront got a cotillion gown. Were you involved in that?

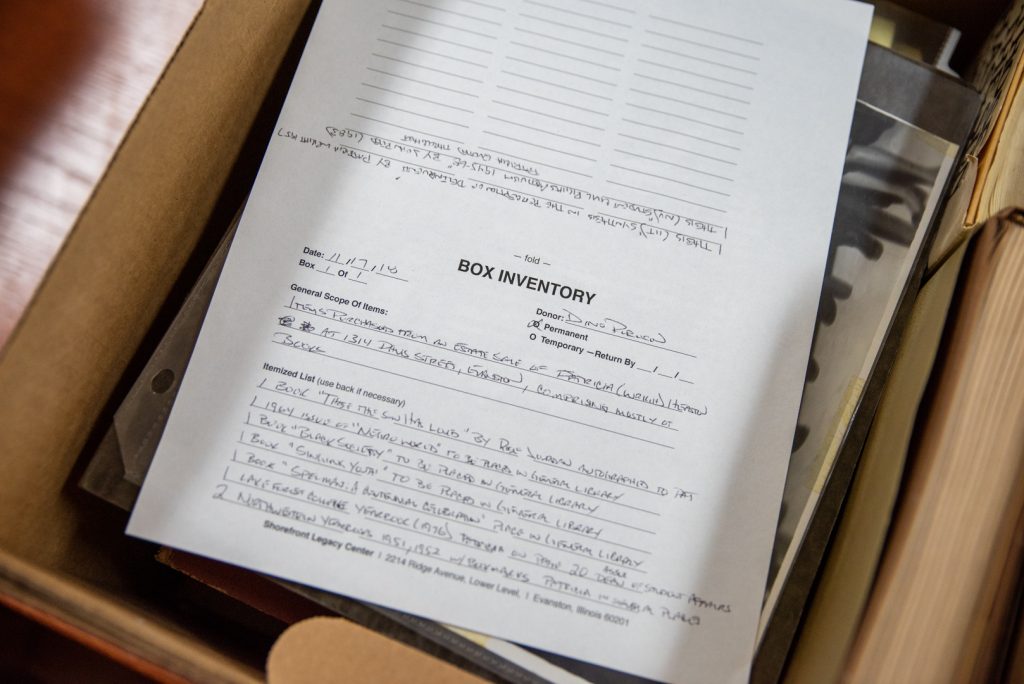

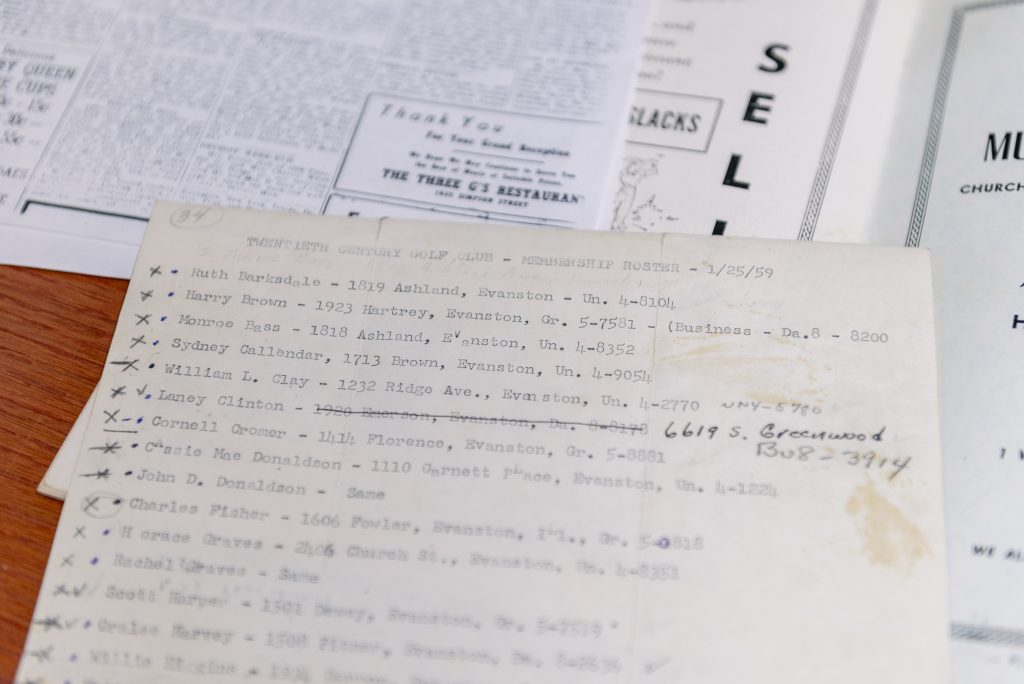

DR: That was me. Yeah, the collections basically were built by me. We have over 500 linear feet of material. Most of those were influenced or retrieved by me. I have a crew of interns that assist with processing the collection and creating finding aids. But I help guide the structure of the archive and the vocabulary [and metadata] that we’re using to hone it down to what’s relevant to our community.

That dress was one of those things I’ve been asking for the better part of 15 years. It is from the 1960s or 1970s, so the odds of it surviving were slim by any margin. Like 113 young women went to the cotillion and [I thought] maybe there’s a chance that somebody still has a dress, and they don’t know they have it. Many times I would talk to somebody and they would say, ”Oh, I just looked at it and it was damaged in the flood. It’s all moldy. I threw it away.” “It got lost in the fire.” “It got lost in a move.” [Or they just] don’t know what happened to it. All these little sad stories. I always have those stories in the back of my mind. So, when these opportunities arise, I jump on them. A cotillion member posted her dress that she just received from her mother, who had recently passed, and she didn’t know what to do with it. She was about to throw it away and she told me, “The dress doesn’t fit. What do I have it for? I’m trying to downsize. I can’t take it with me.” It was just a right time, right place situation. This woman was located in Georgia and I happened to be in Georgia at the same time, but I was leaving the next day.

EU: Oh my God.

DR: I’m looking at a map figuring out how much time I have and I’m 30 minutes away. So I hopped in a car, drove over, and picked up the dress and a few other items. In fact, I’m going down there to meet up with her again. She has some additional items that she wants to donate.

EU: That is such an incredible story. I can’t believe you were there in Georgia! I saw some other photos from your archives that show shirts or patches from a bowling league. I just love those parts of an archive, you know? Clothing is so emblematic of the time and they’re truly lived history. It’s really exciting that you’re able to [continually] build on that.

Drawing us back to the pairing of yourself and Ben Blount for this iteration of Chicago Archives + Artists Project, I’m curious to hear your point of view on what artists and archivists have to glean from each others’ philosophy, training, and creative processes.

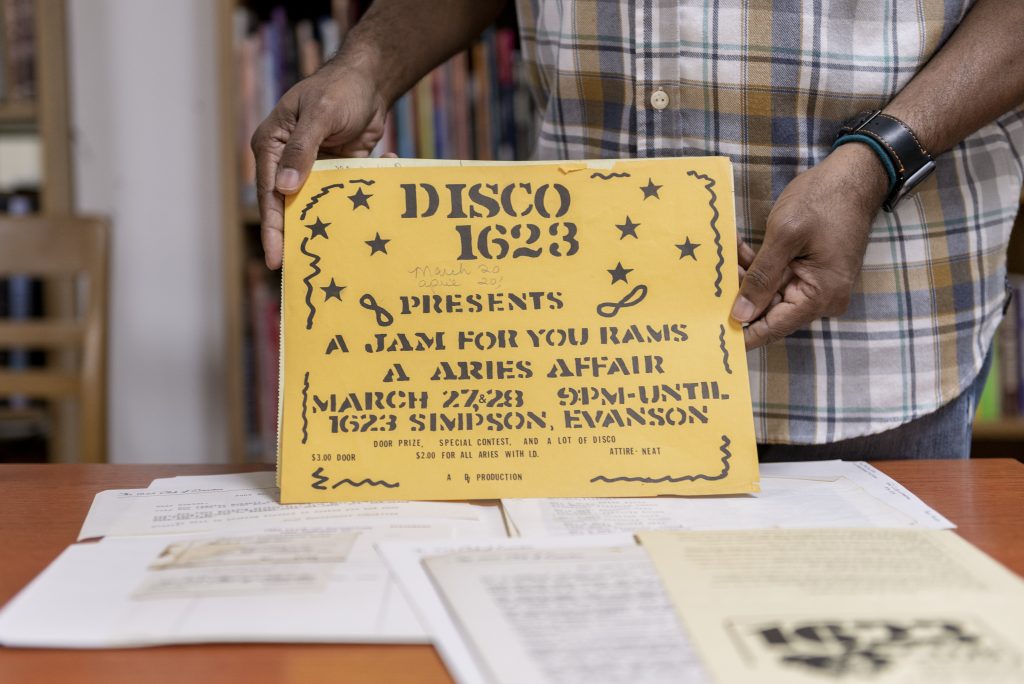

DR: It’s going to be a little unfair because by trade I am a graphic designer as well. I’ve known Ben [Blount] for a little while. He does work in advertising, I was formerly in advertising as an art director. We have the same language; we have the same ideas. I transferred some of my advertising, graphic design, and photography eye into what I do with archiving. What you’re trying to do with archives and art, is capture a moment. How do you illustrate a thought, a concept, [an] idea of movement, and an influence in a way that can relate to many people? The job of an artist is to interpret those things and bring the audience into that thought process and archives serve as the informant: here are the artifacts of things that help inform that movement in that visual representation and that’s, I think, what they share with each other.

EU: Yeah, I definitely agree. I imagine also from a design point of view, there’s so much to draw inspiration from through these archives. I know I love looking through archives personally. The fonts, the colors, and the textures that we just don’t see anymore…

DR: Yeah, I think sometimes it’s like, art is not new, it’s recycled.

EU: I completely agree. We’re constantly recycling the same ideas, but it’s exciting to see how everyone is building on and pushing against these older ideas.

Playing into what you were just saying, how do you see archives shaping artistic futures?

DR: Right. It’s all lived experience. Social services use…archives, performance artists use…archives. They all have to draw from somewhere. Where’s their influence coming from? And a lot of times, these [community] members, even the civic government, all tend to reflect back on history. They dive into the archives to see what was done before, and how should it guide us? If [we look to the] movement of Black Lives Matter, what was done before, in the past? What was it called 50 years ago or 100 years ago? There were radical movements [then too]. The new catchphrase today is Black Lives Matter.

EU: Yeah, and maybe this is with every generation, but we all feel like we have these new, avant-garde ideas, but really they’ve happened before. We have to really look back and take that in and reflect on those experiences.

I’m curious, have you worked with other artists in this archive before, or is working with Ben the first?

DR: I have actually. Shorefront had an artist a while ago who was a painter who was very influenced by the history that was there. He was inspired by four historic figures in the collection and made a painting of each one. We have one of them hanging in our office now. The intent was to switch them out every so often, but we’ve had one hanging for about four or five years now. That was the first time we worked with an artist that was inspired or influenced by Shorefront collections.

EU: How much have you collected yourself? You’re the only one [collecting], right?

DR: Yeah, the collection is all me. So when people ask, “What part of the collection did you acquire?” I say, ”All of it.”

EU: Do you have a favorite?

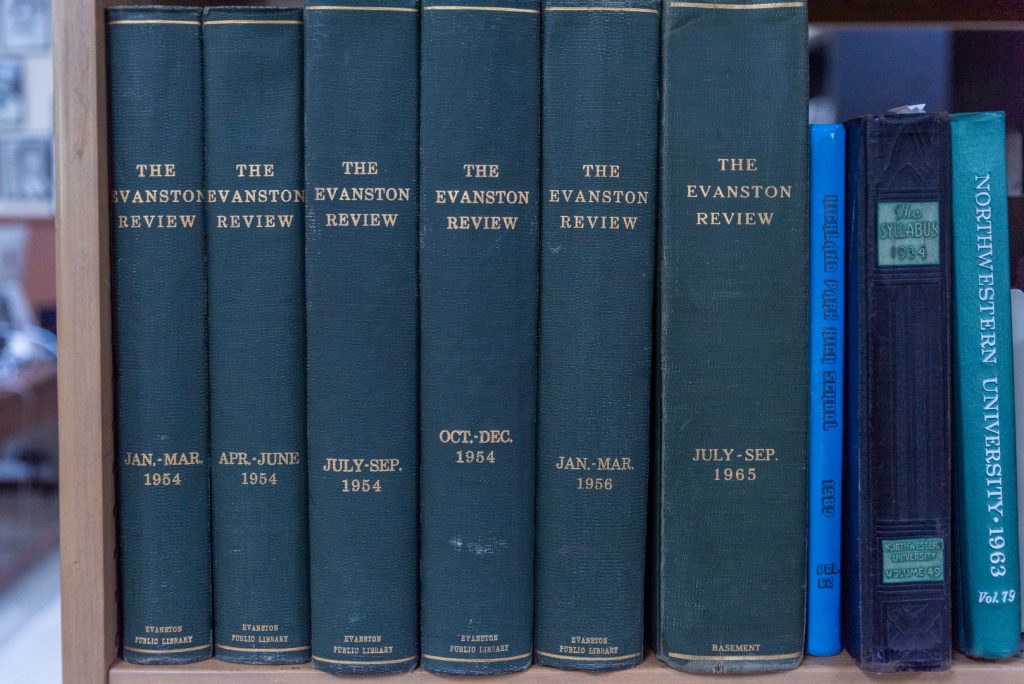

DR: I have lots of favorites. I think one that really excited me though was our first major acquisition. That was the files of Evanston’s first Black Alderman, Edwin Jourdain, who was elected in 1931. They were donated by his family. It was really inspiring… He was very possessive of his files and allowed no one to look through them. In 1971, there was a scholar that was working with him who was not allowed to touch any of the files. All he could do was visit and talk with Alderman Jourdain. [Jourdain] would go through his files and hold them up, but [the scholar] couldn’t touch them. So, over the years, Jourdain’s files stayed in his family home in the basement, and one by one, Jourdain’s children left and moved on. When the last sibling decided to sell the house they were vacating the space, but there was still the huge question of what to do with Dad’s files. One of the sisters advocated for the files to go to Shorefront. Believe it or not, when I got there, I was not allowed to go in the house to get [the files]. We actually had a contractor who was working on the house go down in the basement and bring them out to my car.

It was very interesting, but I didn’t argue about it either way. Then I was told not to look [in the files] until another family member went through and approved their release. I had them in my office for about a week, but I let the siblings know that I have to at least make sure there’s no water damage, mold, or infestation, but that I would not peruse the files. They allowed me to do an inspection and then about four months later, the youngest sibling came to go through the files and give the stamp of approval to archive and release them. I think that that epitomized our first major acquisition, established the trust that we have in the community, and it was a major piece of history that could have been easily lost with that move. His archives date back to 1880.

EU: That’s incredible. You know obviously, archives are about looking back, you are constantly reaching out about past histories that are lost or narratives that haven’t been brought to light. I’m interested in your take on the future. How do you incorporate the present and the future at Shorefront?

DR: One of the things that we focus on with Shorefront is actively collecting for the future. We not only look for things that are in the past, but we’re contemporary collectors as well. When events are happening now we go to them. We’ll photograph businesses that open up. When I look through the past histories of businesses, I’ll see a name but no images, no ephemera left [behind], only its listing in the phone book. I try to gather these now while people are here. I’m glad I do that because some of the businesses we have captured no longer exist. That proof that they were there means a lot.

We also talk to a lot of high school students and tell them, “Here’s your opportunity to make your mark and be part of the archive. Think about it this way: Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was once a teenager. He had no idea he would be famous, but wouldn’t it be cool to have his high school archives to see what his teenage years were like?” For a while, we had a program called The Legacy Keepers. It was a youth-based program and we had three different projects they could pick. We facilitated whatever they chose whether it was a blog site, a photography project, or a newspaper. The most popular one was a photography project, but the more interesting one was a group that one year made a blog site called “A Day in the Life of the Team.”

We would have sessions once a week and we talked for about 40 minutes, just, “How’s your week? What did you do?” The last 10 to 15 minutes were them blogging about what we just talked about and their perspectives. The stories took all kinds of directions. One [student] talked about a trip she was preparing to take to China and Japan. She did half a blog in English and the other half in Japanese.

EU: It’s important to let young kids and teens know that their lives are important and we want to hear their stories. Also, you know, it’s good for them [to record their lives]. I feel like I missed out on a lot by not journaling or having a diary when I was younger. There are so many things I wish I could reflect on now.

DR: I just could never stick with it [either]. I would do like four or five entries, and they’re like half-assed. I would let it sit there and then find it like five years later [and be] like, “Oh yeah, I have this journal, maybe I’ll do another entry.” And now it’s in storage [again].

EU: Waiting.

DR: I think I ripped out pages, you know? Like, “I don’t like that anymore.” I was like, “I’ll use it for scrap paper to take notes like on a phone call or something.” It’s not really a journal, it’s just stuff. Random stuff.

EU: I know. Maybe one day we’ll return to them.

DR: Well, I did something pretty creative when COVID hit. Because I’m a graphic designer, I like to create and ended up making a dimensional scrapbook.

EU: Oh, what is that?

DR: It’s like a case about three inches thick. It’s basically a shadow box I hinged together to make a fold-out box. I created this exterior design [with] many layers of pockets and cubbies that I put dimensional objects in like written words, a map of the United States, airline tickets, stickers, a family tree of sorts that has some historic documents, high school and college ephemera, and some photographs that I’ve taken. It’s a lot of different things. It [also holds] a flipbook of [my] high school and college years, my first job, family life, my marriage. So that was fun.

EU: Do you think that you were inspired by the archive to create this?

DR: I was, yeah. I was inspired by a couple of scrapbooks [we have]. I’m like, “I want to do a scrapbook.” So I did. That’s going to go into the archives, too. So, I guess that’s my journal [and contribution].

EU: I was also curious if there are archives that you looked to or are inspired by for the mission and work of Shorefront.

DR: I’m more focused on archives remaining independent and controlled by the community they originated from. That’s what is important to me. There could be some great collaborations, but I’m not necessarily fond of a major institution owning it. Then the onus goes to the institution and the community has to ask permission to see their own history. That doesn’t sit well with me.

EU: I totally understand that. These big institutions have so many archives that truthfully so many things [can] get lost.

DR: Right. And so many times these institutions argue they have the resources. Yes, of course, you have the resources. I think a better help would be to make sure [community archives] have the resources that we need to remain independent.

EU: That’s true, I completely agree. You’re in Evanston so, do you have ties to Northwestern at all?

DR: Full disclosure: I do work at Northwestern.

EU: So do I, actually.

DR: I work at University Press as the production manager.

There have been discussions. I had one colleague say that I should really consider giving [the Shorefront] archives to Northwestern. But why? Because Northwestern is suddenly interested in Black archives now? For the last century, they were not.

Shorefront was born because others were not interested, but now we’ve found relevance. Other communities thought there was nothing relevant about the Black community [in Evanston] until Shorefront came along and proved differently. There are a lot of hidden stories, hidden facts, and transformative movements that have happened here that regular history has ignored. So why do you want it now that the community has shared its stories? Now you think it’s relevant. Now you want it because now you can monetize it. You can write a grant, you can get [the grant]. You know, create a white paper around it, write a history book around it and say, look what we discovered. No, you did not discover it. Don’t Columbus us.

EU: [This is all] very important. I was inspired when you were talking about keeping it in the community. There are two branches of Shorefront: the press and the center itself. I see the archival work happening outside of the storage [of materials] in your attempts to help local sites gain historical landmark status. I’m curious about your relationship to these historical buildings and sites, and how you started to help them gain official status.

DR: A lot of communities across the nation have historic districts, conservation districts, or the oldest house in the town they’re saving. What was interesting about a lot of those criteria is that they’re really based on history and the further back you go, the more relevant it is. [Also helpful is] if it’s designed by an important architect. Homes that were mostly in Black communities did not have the age or architectural status. The criteria were designed to keep a lot of [those] communities out. There was a group in the 90s called Preserving Integrity Through Culture and History (PITCH). It came around the same time I started doing research [on the history of Black Communities on the North Shore] and they were interested in what I was doing. It was led by the alderman at the time but it was community residents that really liked what I was doing. They encouraged me to get involved in PITCH and I started doing early bus tours learning history, engaging, and getting a dialogue going. The work was a two-member assessment of the entire Black community, block by block, house by house. We figured out the style of the houses, who lived there, and the historic significance of the structures in these areas. The idea was to create a conservation district, but it got more and more complicated. The community didn’t buy into it full-heartedly because they were concerned about how it would affect the value of their homes and if it would restrict home renovations. Those questions put a stall on a lot of things. It kind of got shelved.

DR: I pursued it again in a different way with historic markers like kiosks saying this is now a historic district. That proved to be costly. We didn’t know what those communities were gonna say and what the pushback would be, and we didn’t have the money. But then former Alderman Robin Lee Simmons was really looking at re-energizing the community. She came to me when they wanted to create a historic district and asked me to lead the way. I said, “Hey, that work has already been done. And in fact, let’s get some of the members who founded PITCH involved in this and hash out some ideas.” The two members of PITCH, myself, and the alderwoman met…Sorry for being long on this…

EU: No, no, this is what I’m here for.

DR: Later, walking on the sidewalk I saw a brass plaque embedded in the sidewalk [with the mark] of the manufacturer or the concrete craftsman that laid the sidewalk. And I thought, “Oh, that would be a good idea to put a mark on the sidewalk in front of properties.” So… the alderman and I went to the Preservation Council. There was a long wait list because people were talking about their buildings, they were architects and planners talking about the historic homes in the district. Before the meeting started, they said, “Dino, we know why you’re here, we’re gonna start an ad hoc committee. We would like you to head it and we’d like to see what you would get done.”

We were meeting on a monthly basis to envision what this could look like and it went back to [the idea of a] Conservation District with all the tasks focused on one area. I had to remind everyone that we used to live all over instead of just one area. We can’t really make multiple conservation districts, can we? How does that look? And the plan started getting complicated. So, when it got down to the sidewalk markers, I said, “Why not just say all of Evanston is the district, and we can mark [specific] areas with plaques embedded in the sidewalk?” The Preservation Council loved the idea. I wrote the ordinance, it was approved by the Preservation Council, then it was approved unanimously by the City Council. I had the markers fabricated and numbered, and now we’re starting to install them. We have about four of them installed now and what’s cool about this is that the community submits applications about why a structure is historically significant from their [own] lived experiences. Another group from the community will review the applications and approve them. Once they pass, the markers are set. All of this work has led to the formation of the African American Heritage Sites Program which now officially oversees the designation of these sites.

EU: That’s so lovely having the community come forward and pitch the reasons instead of an outside force doing it. I’m sure you’re also able to start to make connections between these community members and Shorefront and build a stronger community.

DR: Right, and we’re building our collection with it. The community members are doing the research and the application goes into the archive, so it captures another part of history that maybe would get lost.

EU: Amazing. What was the most recent one you installed?

DR: We installed two just last week. One was in front of the house of the first Black resident of Evanston, Maria Murray Robinson. She came [to Evanston] in 1855, and was living in her house by 1860. The other was the Evanston Sanitarium, which was a segregated hospital established by Isabella Maude Garnett and her husband, Arthur Dalliance Butler.

The two we did earlier in the summer were at the homes of Edwin Jourdain, who was the first Black Alderman, and Lorraine H Morton, the first Black Mayor of the city of Evanston.

EU: And then you said there’s still a few more that you’re planning to do for more.

DR: Yeah, we have four more located mostly in downtown Evanston. We purposely spread the first group of markers across Evanston so people would see where [Black Evanstonians] were living.

EU: Yeah, I imagine that’s really important. I’m new to Chicago and Evanston, I’ve only been here a year. You can still see traces of segregation throughout the city and I feel like this is maybe a way to point to how things were.

DR: Exactly, exactly. The mission is to display how diverse the community was before the 1900s, Jim Crow, and segregation.

EU: To tie it back to you, you said you came into archiving through your grandmother and genealogy. Is your family based on the North Shore?

DR: No, my family heritage is still in the South basically: Arkansas and South Carolina. During the Depression, a lot of my ancestors came to the Chicago area. For a long time, we had a huge presence in Chicago. Then in 1980, my parents moved to Evanston. Well, we actually moved to Glenview first. While I was in Glenview, I integrated my elementary school. We moved, and there were [around 20] Black people living in Glenview. [We were] the only Black family that was not associated with the Glenview Naval Air Station at the time.

EU: You [and your family] were clearly a part of Glenview’s history. I think that also speaks to your motivation to talk about, learn, and preserve history. It’s incredible. Is there a Glenview Historical Society that you’re in touch with about your experience?

DR: I haven’t been in touch with them. You know, it’s funny because as long as I lived there, I don’t think I’ve ever set foot in [the Historical Center there]. I had questions about history, though. I’ve always been interested in history.

My question, especially being the only Black kid in the school, was always who wrote this history? Why is the United States history course so long but there’s a small section on slavery that is exactly one paragraph long? So I started reading, questioning things in my mind, and rereading the chapter titles differently. Like, the expansion of the West, you mean, the slaughter of the Native Americans? And yeah, the Industrial Revolution is [actually just] child labor, you know?

EU: So [you were] really getting straight to the point.

DR: What has bothered me for a long time is whose stories are missing? What stories are missing?

EU: You’re really taking from that childhood interesting curiosity and putting it to work now. Thank you so much for your time. It’s been great.

Chicago Archives + Artists Project: Case Studies in Collaboration serves as a site for new archive-inspired explorations, a directory of Chicago-based archives and collections, and a printed space where past artists, archivists, librarians, curators, and other collaborators can reflect on 5+ years of the Chicago Archives + Artists Project.

The book features two new artist/archive pairings with printmaker Ben Blount who spent time in the archives of Shorefront Legacy Center, and artist/poet Natasha Mijares who explored the Latinx art collection at DePaul Art Museum. Edited by Kate Hadley Toftness, with support from Tempestt Hazel, Christina Nafziger, and Persephone Van Ort. Designed by Matthew Austin of For the Birds Trapped in Airports.

The book also features writings from Oscar Arriola (Zine Mercado/Chicago Public Library), Sara Chapman + Dan Erdman (Media Burn), Sky Cubacub (Rebirth Garments), Meg Duguid + Michael Thomas (Culture/Math), Marc Fischer (Public Collectors/Temporary Services), Kate Hadley Toftness (Sixty), Tempestt Hazel (Sixty), Ivan LOZANO (CA+AP Artist), David Maruzzella (DPAM), H. Melt (CA+AP Artist), On the Real Film (CA+AP Artists), Jennifer Patiño (Sixty), Jessica Pushor (Chicago History Museum), Morris “Dino” Robinson (Shorefront), Robert Sloane (Chicago Public Library), Nell Taylor (Read/Write Library), Lauren Shadford (Voices of Contemporary Art), Darryl DeAngelo Terrell (CA+AP Artist), and more.

About the author: Elizabeth Upenieks is a Chicago-based curator, writer, and art historian. She earned a BA in Art History from the University of Texas and an MA in the History of Art & Architecture from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Her most recent projects include What We Do in the Shadows and PLATFORM 26: Myoung Ho Lee, Tree…#2 at deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, Lincoln, MA.

About the photographer: Ryan Edmund Thiel (they/he) is an artist, photographer, and graphic designer living in Chicago. Their work across media explores healing, liberation, and empowerment for the individual and collective. Their mission is to support artists and organizations whose values align with care, social justice, and collective organizing. Ryan is also the lead graphic designer for Sixty Inches From Center and co-lead of Sixty Collective. View their work at ryanedmundthiel.com and @talldarkandryan on Instagram.

About the photographer: EdVetté Wilson Jones is a Chicago-born artist, photographer, poet, performer, and storyteller. During their childhood years living at the Cabrini Green housing projects, EdVetté was introduced to acting through the work of Chicago theater legends and veterans Jackie Taylor, actress and founder of Black Ensemble Theater, and the late Patrick Henry, founder of Free Street Theater. From there, EdVetté’s practice grew to include not only acting, but screenwriting, storytelling, poetry, journalism, fashion, and more. To learn more about their work, visit their website at edvette.com.