I had a basic sense of the urban history of St. Louis: deindustrialization, redlining, and white flight, all reflected in a downward sloping population chart and an interactive online map whose shaded regions shuffle along radial axes further and further apart over time. Nonetheless, I was surprised as I walked downtown. Tallish, newish buildings lined a wide boulevard dotted by tap rooms and cafes dealing overpriced salads to the only other pedestrians out and about: a small cluster of people in color-coordinated tee shirts (a school group, perhaps) and an occasional professional-looking person in a suit.

I had arrived that afternoon via the Amtrak Lincoln Service Train No. 301 from Chicago, sleepy and hungry, and after taking care of both concerns with overpriced salad and bottomless coffee, and while waiting for a friend to come pick me up after work, I sought the one place in the area recommended to me by people in Chicago, the City Museum. Sensory overload was sudden and overwhelming. I now understood the meaning of the tip to “bring knee pads”: here were probably no less than a thousand small people (children) with their respective big people (parents, grandparents, guardians, chaperones): members of the first set screaming and scrambling with members of the second in hot pursuit, crawling on protected knees inside the twists and turns of metal grating and salvaged industrial parts that make up a giant playground stuck on the side of a former shoe warehouse in what used to be St. Louis’s garment district. A long line of school buses hovered nearby, waiting to return their passengers to all corners of the city.

I was in St. Louis to write about a two-day festival called Dwell in Other Futures that took place April 27–28. I didn’t know what to expect from an event described as a “festival of art and ideas” but I was drawn to the questions put forward in its program: How do images of the future shape the city in the present? What competing futures are emerging in the urban fabric? The seeds, funding-wise, came from a Washington University initiative called the Divided City, which gives a clue to its sociological context. It was organized by Gavin Kroeber, Tim Portlock, and Rebecca Wanzo – Kroeber and Portlock are artists; Portlock and Wanzo are professors at Washington University (the former in Design and Visual Arts, and the latter in Women and Gender Studies).

The opening events didn’t start until evening, so after some more gawking at the City Museum’s cacophonous clamberers, I ambled on and plonked myself on a picnic table bench outside the Bootleggin’ BBQ Tavern to wait for my friend. It was hot and I was wearing too many layers. The street felt empty again.

Over the following two days, I wondered as much about St. Louis the city as Dwell in Other Futures the festival. I had only driven through St. Louis before and had little personal experience to go off of (my mom, uncle, and nana did live in St. Louis for three years, but at a less-than-best time in their lives). Images of the past more immediately colored my vision of St. Louis than images of its future did: how “post-industrial” sits at the tip of the tongue, the demolition footage of the Pruitt-Igoe housing projects, a mammoth statue of a Cherokee figure on Cherokee Street, the aforementioned map and chart. (A favorite image of the city’s past was one conjured for me by a Lyft driver who told me of the network of tunnels beneath the city that he had heard were possibly linked to the Underground Railroad. He told me that one had recently collapsed and swallowed up someone’s car. A cursory search online tells me that the former is probably not true, and I can’t find anything to confirm or deny the latter).

In trying to piece together an understanding of St. Louis, I found myself recalling times in Detroit, a city that has become emblematic of the post-industrial urban Midwest. The way images (of burnt-out houses and fallen-down factories) work to shape an outsiders’ knowledge of Detroit is so clear as to have formed a genre: “ruin porn.” As the name suggests, such images are seductive and untrustworthy. The image of the vacant city is a placeholder for a history (see: chart and map), and enables many things to happen – land speculation, and development, and displacement, and all kinds of complex things on the spectrum of good to bad. If I took away one thing from Dwell in Other Futures the festival, it would be a need to pivot attention away from what’s not there to what is.

On the whole, the participants in the festival mixed or avoided disciplinary categories, but there were three general tacks taken toward the two guiding questions: art (writing, sound, video, performance, installation, music), scholarship/education (as members of academia and otherwise), and community organizing/planning (activism, architecture, civic engagement). Most of the participants were based in St. Louis; a few people came from other mid-sized cities dealing in post-industrial futures (Newark, Detroit); several participants live or work in New York City, and one came from London. There were musical performances and video screenings. There was an art gallery. There were PowerPoint presentations, panel discussions, and a performative panel discussion. There was burlesque. There were children and adults and college students in attendance. There were two participants who couldn’t attend and therefore presented via “video postcard.” There was an activity in the grass involving spray paint and megaphones. There was dancing. There were snacks.

The opening night took place at .ZACK (pronounced “dot Zack,” after the grandchild of the Kranzbergs, of the Kranzberg Arts Foundation that funds it), a newly renovated four-story, Egyptian revival building that formerly housed a Cadillac dealership in what’s now the Grand Center Arts District, west and slightly north of downtown. At the time of its opening in 2016, the Riverfront Times reported that .ZACK was the first arts incubator in St. Louis. I arrived perspiring, having dressed for the 40-degree weather I had left in Chicago that morning (the sun was beating down in St. Louis). I took a seat in the cooled, proscenium-style theater on the first floor.

Though it was organized around superstructural themes (futurism, urbanism, and race), the festival began on a personal note. This had a lot to do with the reverence for its keynote speaker and thematic cornerstone Samuel Delany, who is the sort of writer that, depending on who you talk to, is either a total legend or totally obscure. (I first learned of him via P.Michael of the avant-gospel noise band ONO, which holds a similar status in Chicago). Gavin Kroeber told me that his and the other two organizers’ interests first intersected at Delany, who is claimed by science fiction, Afro-futurism, queer studies, urban studies, rural studies, and just about any field that exists in interstices and hyphens. The organizers, Kroeber told me, were interested in how Delany could draw people from many different scenes and fields and put local concerns in conversation with global themes. His novel Dhalgren (which tracks the communities of people living in an otherwise abandoned, dystopian, fictional Midwest town) and his essays in Times Square Red, Times Square Blue (a first-hand account of the non-fictional queer sex and interclass communion that took place in the porn theaters of pre-Disneyfied Times Square) were referenced throughout the festival. Both stories dwell in worlds left behind or displaced in the process of renewal. On this evening, however, the 76 year-old writer read from his last novel, Through the Valley of the Nest of Spiders, first quoting from a review that named it his worst novel: “Incest and glory holes do not a sci-fi make.” He seemed pleased. For roughly 40 minutes, he narrated an orgy that occurs between several men, young and old, in the back of a pickup truck in a mythical rural town. “I’m addressing rural futurism,” as he said.

Delany: “I hope we have a future.”

Three people had been invited to respond to Delany’s influence on their work and the questions posed by the festival: Treasure Shields Redmond, a metro St. Louis-based poet and social justice speaker; Terrance Wooten, a fellow at Wash U studying the intersections of gender, sexuality, and homelessness; and Sophia Al-Maria, a London-based artist and writer who grew up between Qatar and Washington State and whose work deals with strains of futurism in the Persian Gulf. They all presented in the form of personal narrative, and I noticed that each addressed a false utopia: images of the future that leave certain people out. During the Q&A portion of the night, I asked them to describe a future they each desire:

Al-Maria: “I come from a place where the future that was imagined by white men in the 20th century looks like it’s happening. The Gulf has a lot of shiny glass buildings and a lot of money and a lot of alienation and disjointment from, for example, the climate. But the future I’m more interested in is one that’s not around the ideas of infinite growth…more of a Delany universe, frankly, where there’s less structures around – there’s no patriarchy; there’s love and fluidity and nonbinary ways of being.”

The first to respond was Al-Maria, who was jet lagged and, I sensed, nervous to present in front of an idol. I had read about Al-Maria’s work on “Gulf futurism” while riding the train that morning – observations on the rapid erection of high-tech mega-cities in the desert landscapes of the Persian Gulf. I was surprised and touched by the more intimate experience of urban life that she described during the panel via a memoirish letter recounting a romance that began in Cairo and ended devastatingly in New York City. Along the way, she tried and failed to finish Dhalgren but, as she told it, found courage to keep creating in reading Delany’s The Motion of Light on Water.

Wootten: “I feel like as a black queer subject, I spend a lot of my time waiting for the tomorrow that never comes and having to imagine possibility as always future. And I’m in a moment in my life – now, tomorrow might change – where I’m really invested in now, and this now, right now, looking out, looks like the future I imagined was never possible. Where I would be standing here comfortably in my own skin as a black queer subject, with Samuel Delany on the end and red wine in my lap, and I just showed pictures of penises?!”

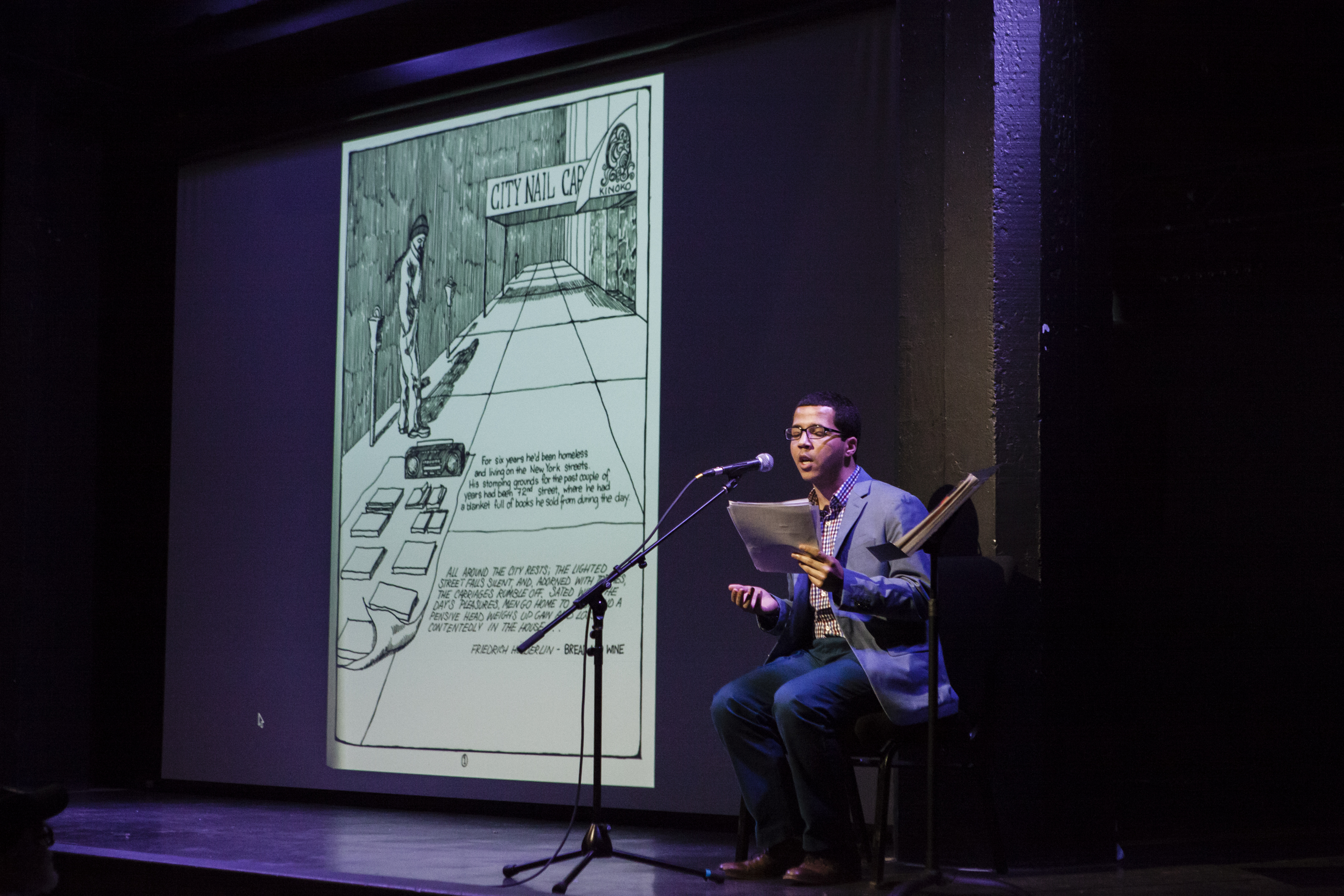

Terrance Wooten was second to respond. He had grown up, closeted, in rural West Virginia, dreaming of moving to the Big City in order “to spread my rainbow-colored wings, and publicly lust after and be in community with other men like me.” That opportunity came (in a fashion) by way of Columbus, OH, where in a queer bookstore (now replaced by an expensive restaurant) he bought Delany’s graphic memoir Bread and Wine: An Erotic Tale of New York in a flushed attempt to impress a gorgeous man and self-proclaimed Delany fan. That memoir describes Delany’s real-life romance with Dennis, a street-homeless man who was selling books off a blanket when they met. For Wooten, whose academic work addresses queerness and homelessness, this was a radical depiction of homelessness as liberatory and of homeless people as desirable, contradicting the hygienic euphemisms that often accompany urban change (“cleaning up,” “beautifying”).

Redmond: “I’m mothering a 17 year-old Black boy who is very bookish, and who I binge-watch Dr. Who with…and an 11 year-old Black girl who is very capable and brave. I imagine a future where I am not always making concessions for their bodies. It’s hard for me to imagine that place, and I know we have to imagine a place before we can actually be there.”

Treasure Shields Redmond grew up in Mississippi and spent summers in East St. Louis, IL, just on the other side of the Mississippi River from St. Louis. A dominant image of East St. Louis includes poverty, strip clubs, and vacant lots, and of Mississippi as “holding the patent on racism and homophobia,” but, through a series of poems, Redmond shared others: the queer teenagers who lived next door in the projects and the women who everyone knew to have a relationship beyond the suggestive “roommates.”

At the cocktail reception following the presentations, Gavin Kroeber told me: “St. Louis is a city that speaks loudly about its future.” (I’ve been feeling badly about the beer I spilled on the floor in my hustle to jot down that quote; if the .ZACK cleaning crew is reading this, I apologize.) Every announcement about potential construction – a new Rams stadium, the National Geospacial-Intelligence Agency – becomes a debate for the future of the city, he said. And ever since the uprising in Ferguson, a 20-minute drive from St. Louis, the area has become an icon in national media of police violence and the resistance. But: “It seems to us [the festival organizers] the most visionary and radical futures that are emerging in St. Louis are coming more bottom-up, and they are appearing in smaller, often more ephemeral spaces,” said Kroeber. “In activist movements, in queer club scenes, in different artist communities, in the very robust sort of poetry worlds that are emerging.”

In my notebook that evening, I wrote, “the seeds of liberation are among us.” I can’t remember if someone at the festival said that or if it was my own summary of the day’s themes. What stuck in my mind was the glimpse of Treasure Shield Redmonds’s teenage neighbors: a queerness that doesn’t often show up in images of urban queer life. “The archive is here,” she had said, just not fully recognized. This gave meaning to the “other” in the festival’s title and its question of “competing futures.” Though varied in their focus, the visions of the future put forward by the panelists shared a common competitor. Each sought an alternative to a narrative of development and progress that makes the mistake (often willfully) of neglecting what’s already present. That’s what Delany offers in his books: images of the already present, and of the left-behind or displaced. (It was ironic that Delany gave, in my mind, the least visionary vision of the future during the Q&A. Citing environmental catastrophe and overpopulation, he described a sci-fi-tinged future when our reproductive functions are reverse-engineered such that we have to take a pill in order to procreate. Even if the horrible histories of forced birth control as population control were forgiven, I’m skeptical of quick-fix solutions to the earth’s problems which always seem to forget the social and political problems that put the state of the earth in its emergency). Because people anywhere in any place need to survive and tend to find ways to do so, the best bet toward shaping a future is to extrapolate what is working in the midst of “blight” and poverty and homophobia and racism.

What does it take to raise those seeds?

On day two of the festival, the weather had graciously cooled and there was a friendly informality as we drifted from the installations outside to the presentations inside. The site was the Pulitzer Art Foundation, a beautiful, minimalist, and airy concrete building designed by the Japanese architect Tadao Ando, only ten minutes from .ZACK.

Autumn Knight: “Y’all don’t hear the music?”

Looking dead serious, as music blared, Autumn Knight danced her way down the bleacher-like steps on which a crowd of about 40 sat expectantly. At that point, we weren’t sure if the performance had started yet. It was a sharp calling-out of the performance setting: we all had to make a choice to dance or not, and almost everyone chose not to. I turned my recorder on.

Knight, a New York-based artist, locked eyes with three audience members and beckoned them down to join her at the long table at the foot of the stairs. She then welcomed us to the third convening of the La-a Consortium (“la-dash-ah”), a governing body cast in a “post-revolution” future. She introduced the Consortium’s purpose with phrases like, “equity and innovation,” “protect progress,” and “ritual of reinvention.” Dry and decorous, Knight coached the panelists (all Black, on purpose, she later said) through a ceremonious reading of the list of institutions in the Consortium, each one named for a “prominent and creative African-American”: “Their names are evidence of their royalty, their lineage, and thus they must be preserved.” The prickly formality was funny and so we laughed, but the laughter was prickly, too, because it’s not really funny. The joke that is not a joke is that the kind of power that institutional formality signifies is not held by Black people. I wasn’t sure what image of the future this performance projected: one where institutions are Black-led or one without formal institutions at all? I think necessarily both.

Mendi Obadike: “We’re particularly interested in the power of listening and how sound articulates space, and when we talk about that we mean both architectural space and social space.”

A shuffling and stacking of chairs cleared the La-a Consortium and made way for Mendi + Keith Obadike, who gave a more straightforward artist talk. The two artists have been working together for over twenty years across mediums, but are known especially for their sound art and early use of the internet as a creative space. Most striking to me in the context of the festival was their series of works called “Free/Phase.” For “Free/Phase Node 1: Beacon,” they placed parabolic speakers on the tops of the Chicago Cultural Center and Stony Island Art Bank and broadcast traditional liberation songs at morning, afternoon, and evening. For “Free/Phase Node 2: Overcome,” they visited the Edmund Pettus Bridge (site of the Bloody Sunday confrontation on the 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery). Wanting to liven an iconic image that they only know from static, black-and-white photographs, they recorded its contemporary sounds – honking cars, rumbling trucks – and stitched them together for a droning composition of “We Shall Overcome.” “Node 3: Dialogue with DJs” invited the public to sit for private listening sessions with Chicago DJs with deep knowledge of the histories of freedom songs. I took these as models for how to relate to place and to history: through focused listening, through excavation, through remix.

Al-Maria: “I have no faith whatsoever in human ability to engineer things to our advantage…I do have faith in our ability to change our behavior.”

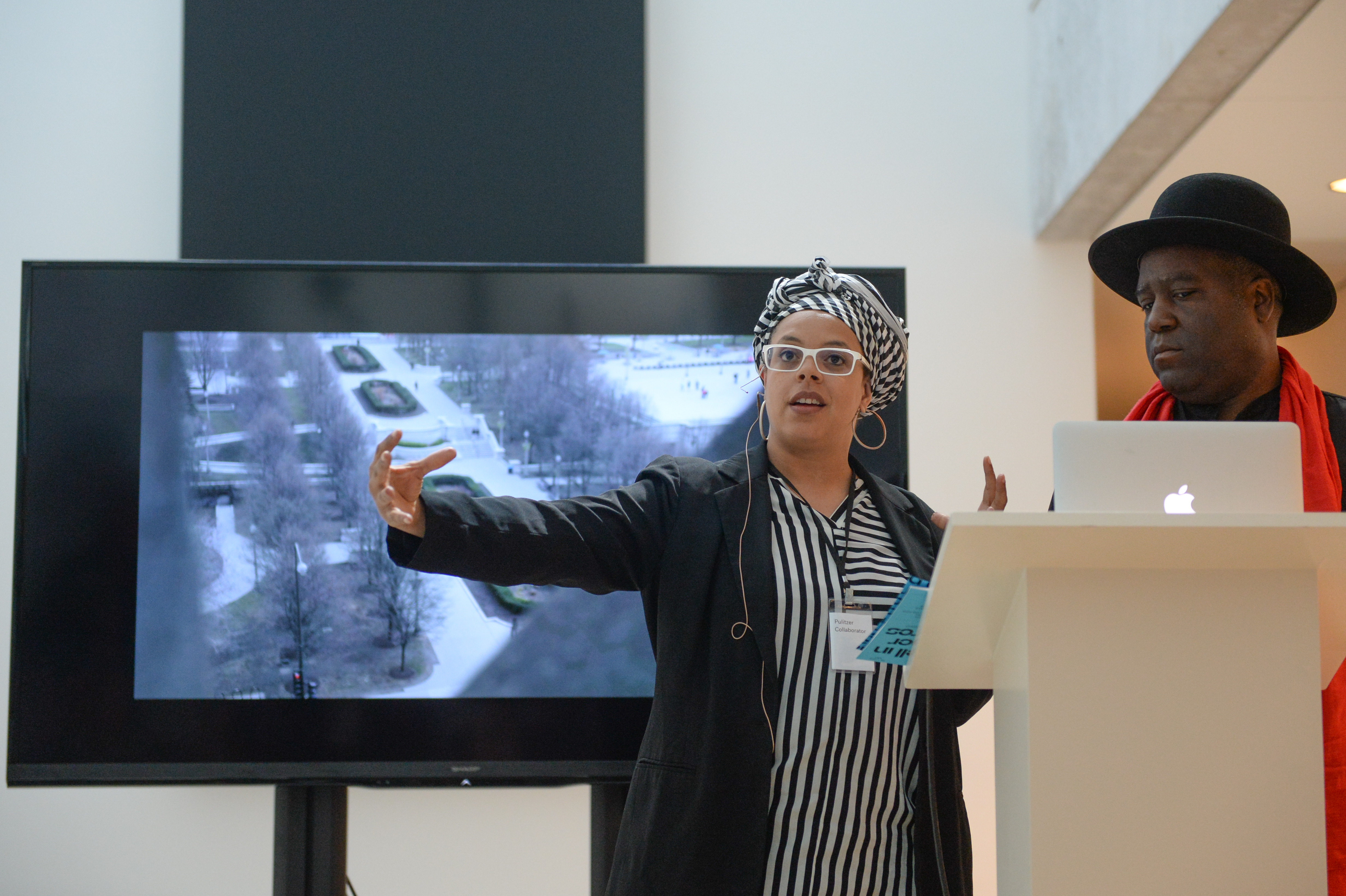

I don’t mean to pick on Delany, but when Al-Maria (who presented again on the second day) said this, it clarified the skepticism I felt of the kind of futurism that his reverse-birth control notion represented. For Al-Maria, this was in reference to a shift in focus in her own work. She had for about ten years been developing work on her observations of “Gulf futurism” (a term she seemed to resent at this point) to address the contradictions in the rapid development of master-planned cities, social inequality, and environmental crisis in the Persian Gulf. She shared an excerpt of her video “Black Friday,” a nightmarish, sort of psychedelic depiction of an opulent shopping mall in Doha, Qatar to illustrate this approach. Her more recent work points the lens at a different scale. “Mirror Cookie” is a collaboration with the movie star Bai Ling, who, shot in soft hazy light with her hair wrapped up in a towel, speaks directly into the camera about self-love and transformation. The tone and content are dramatically different. (“Black Friday” is currently on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago ahead of Al-Maria’s solo exhibition there in September 2019).

There was an hour break in the afternoon. I walked outside. In a field across the street I surveyed the remains of an earlier festival activity, when we had carted around colorful wooden sticks in odd-angled formation, shouted stories and fragments of stories through megaphones, and dragged spray paint across the grass as participants in Eric Ellingsen and Species of Space’s “The earth is blue like an orange.” These activities were billed as “landscape performances welcoming the future now Chouteau Greenway” in reference to the most recent debate for St. Louis’s future, which had just come to a head earlier that week. Three days prior, six design teams had presented plans for the Chouteau Greenway, a proposal for a massive string of parks, bike lanes, and elevated walkways cutting east-west to connect Washington University and Forest Park on the west end of the city to the Gateway Arch along the river. (The winning team, which was announced the following week, included two participants in the festival: De Nichols and Damon Davis).

During that afternoon’s interactive performance, Species of Space members had been dressed in white hazmat suits (another use of the symbols of institutional authority); when I inquired about the spray paint, one told me that the point was to “reappropriate the tools of public utility.” Observing the results, I found that in the hands of the public such tools were wielded for things much more fun than marking sewage lines: for painting flowers and giant fish and large lopsided circles (my poorly executed vision for a restorative justice peace circle-type arena). Alone now, I lingered in the grass and felt the sun and tried to listen like Mendi + Keith Obadike listen: I listened to a sprinkler spit and some birds talk to each other, I heard voices of people at the festival across the street and people just walking by, I heard sirens in the distance, and I looked at the skyline and at the spray paint on the grass and I wondered if it would cause the grass to die and what tomorrow’s people would think when they saw the painted flowers and giant fish and the lopsided circle. I was seized by a feeling of tenderness for this patch of grass in this city I barely know.

Field recording from site of Eric Ellingsen and Species of Space, “the earth is blue like an orange (landscape performances welcoming the future now Chouteau Greenway),” 2018, across the street from Pullitzer Art Foundation.

The festival rounded out with performances by people who work from the sort of ephemeral St. Louis spaces that Kroeber had described, who had each been commissioned to present a manifesto for a future St. Louis: drag performer Maxi Glamour, architectural historian Michael R. Allen, art collective ARTC, activist designer De Nichols, poet Alison C. Rollins, and electronic artist ICE. Ending in this way pushed the festival beyond the realm of interpretive questions into one of strategy and action. During the Q&A, Maxi Glamour pointed out the vast range of mediums used to interpret a manifesto, and I thought about what the flourishing of many futures could mean for a city as segregated as St. Louis, as Chicago. Where debates of the future so frequently coalesce around residential neighborhoods – who’s moving in and who’s being forced out by rent hikes – where you dwell matters. As for how to dwell, I took simple methods back to Chicago with me: pay attention, spend time, linger, learn the history, develop relationships, listen.

Featured Image: Participants in Eric Ellingsen and Species of Space, “the earth is blue like an orange (landscape performances welcoming the future now Chouteau Greenway),” 2018, presented as a part of Dwell In Other Futures: Art / Urbanism / Midwest. Pulitzer Arts Foundation, St. Louis. April 28, 2018. Photo by Michael Thomas.

Starting from the proposition that art-making is world-making, Sasha Tycko combines community organizing and curatorial work with writing, music, and performance. Tycko is a founding editor of The Sick Muse zine and an administrator of the F12 Network, a DIY collective that addresses sexual violence in arts communities. Find more on IG: @t_cko. Photo by ColectivoMultipolar.

Starting from the proposition that art-making is world-making, Sasha Tycko combines community organizing and curatorial work with writing, music, and performance. Tycko is a founding editor of The Sick Muse zine and an administrator of the F12 Network, a DIY collective that addresses sexual violence in arts communities. Find more on IG: @t_cko. Photo by ColectivoMultipolar.