Featured image: Darlene Blackburn in her living room on the South Side of Chicago, 2019. Photo by Wills Glasspiegel.

This essay provides context around Dancer of Time, scholar Wills Glasspiegel’s short film with dancer/choreographer Darlene Blackburn. Glasspiegel connected with Blackburn in early 2019 while doing research for Fleeting Monuments to the Wall of Respect, a new anthology edited by Dr. Romi Crawford. Glasspiegel’s contribution to the book, “Dancing the Wall of Respect,” was a photographic essay focused on Chicago Footwork, the improvisational dance he has been documenting since 2009. In this new piece for Sixty, he expands upon Dancer of Time with further discussion, imagery, and extended commentary from Blackburn.

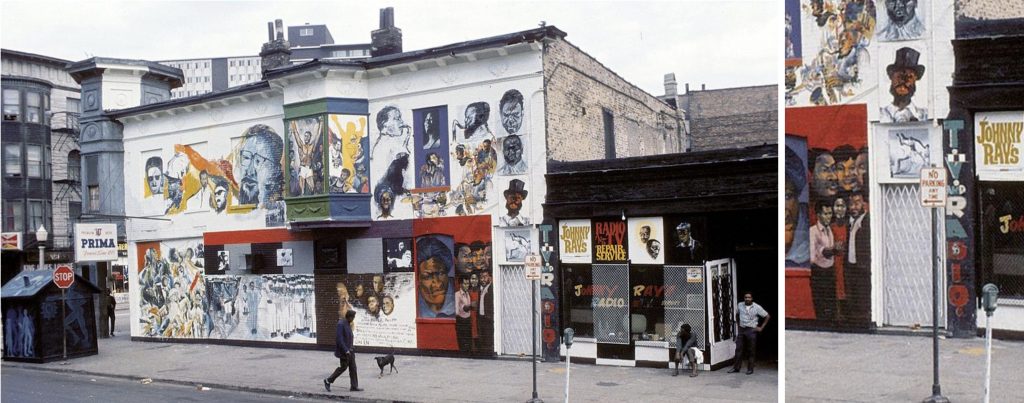

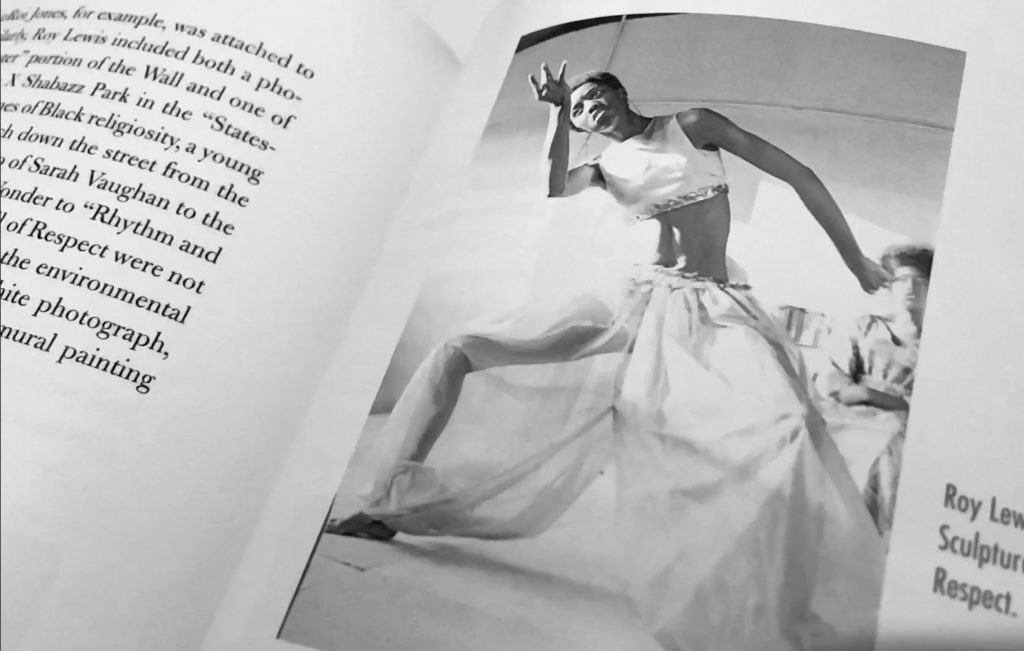

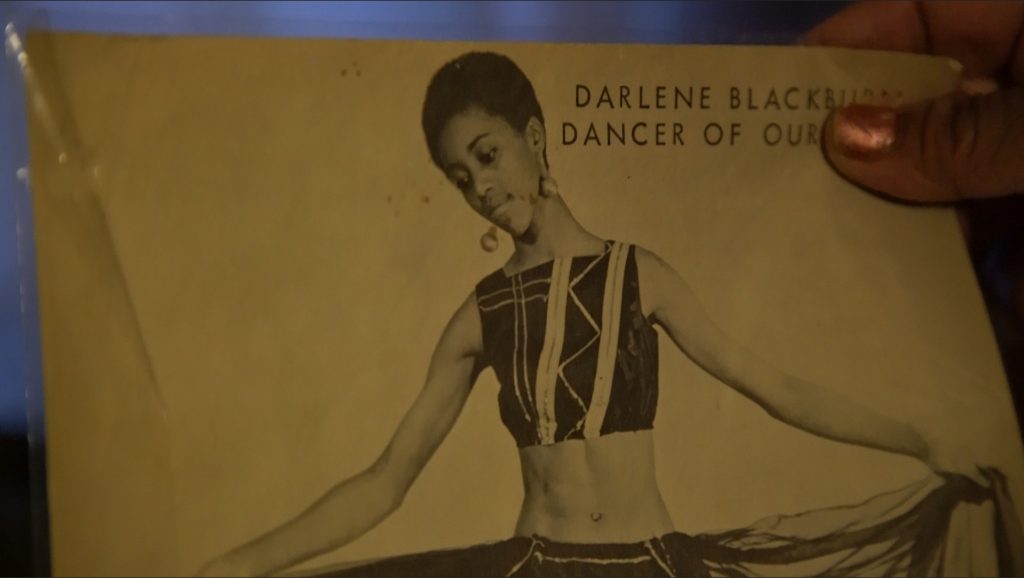

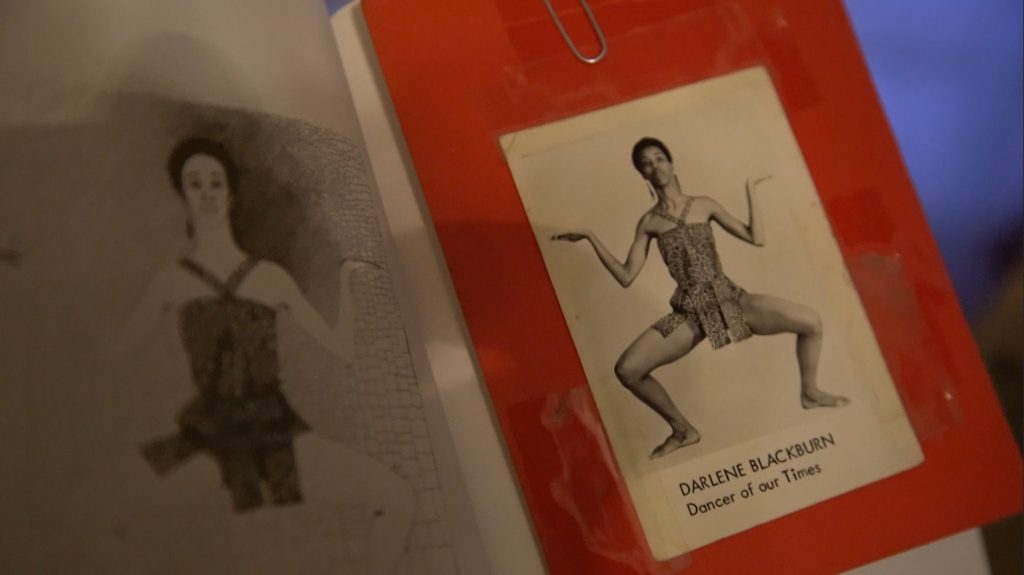

I first learned about dancer Darlene Blackburn’s work through The Wall of Respect, an iconic, long-demolished mural on the South Side of Chicago. Erected in 1968, The Wall featured an array of Black leaders, musicians, politicians, and sportsmen, including Mohammed Ali, Gwendolyn Brooks, Marcus Garvey, and Aretha Franklin. Darlene was the only dancer included, her black and white photograph pasted below a portrait of Ornette Coleman. She was also one of the few Chicagoans depicted on The Wall.

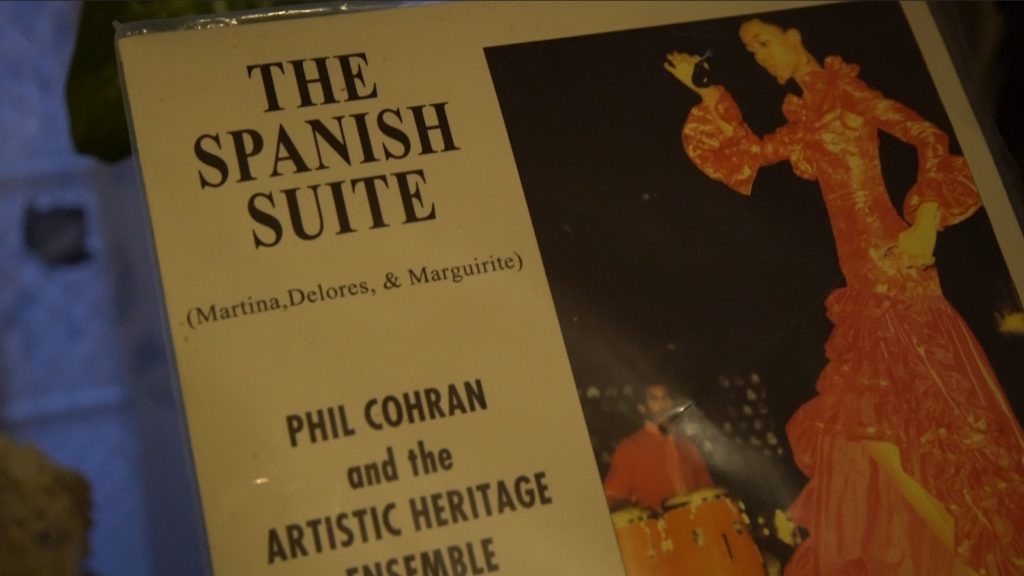

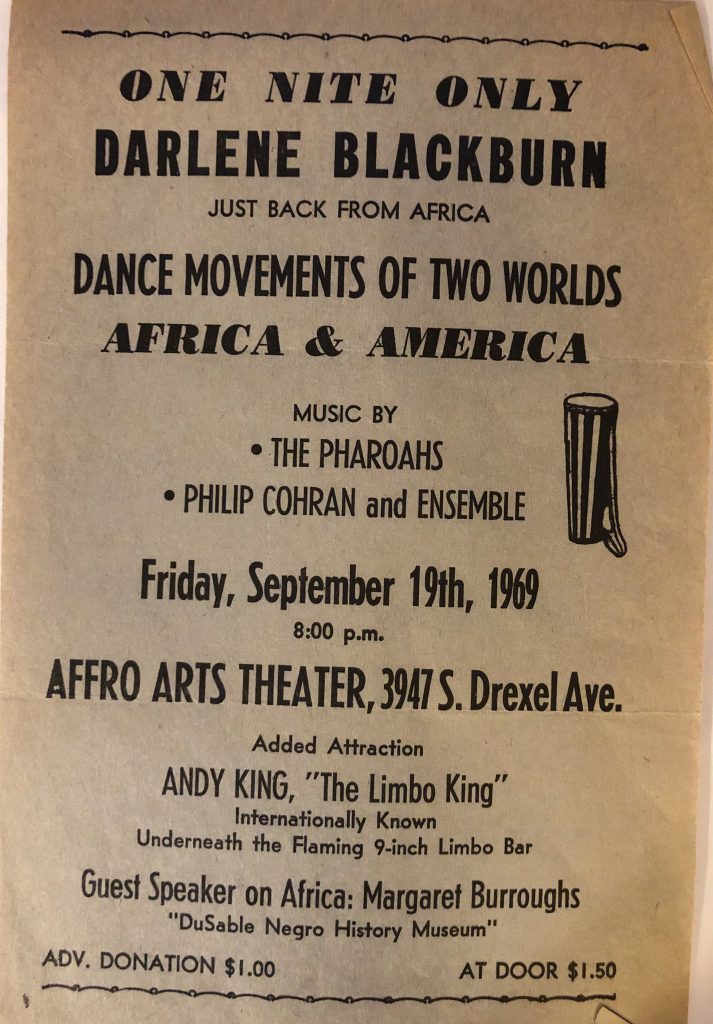

As a Chicagoan and filmmaker focused on dance history, I was drawn to Darlene’s story and perspective. I grew up listening to jazz music from the South Side, including records by multi-instrumentalist Phillip Cohran, but it wasn’t until recently that I realized Cohran and Darlene were lifelong collaborators. “I’m dancing to his music in the picture of me on The Wall,” she says. From art to life, Darlene also performed with Cohran in front of The Wall on several occasions, dancing to his piece “Black Beauty.”

Dr. Margaret Burroughs, artist, educator, and institution-building co-founder of the DuSable Museum and the South Side Community Art Center, was another important influence for Darlene. Burroughs met her at DuSable High School in the mid-1960s. After seeing her dance, Burroughs told her point blank: “You need to go to Africa.” With Burroughs’ support, Darlene traveled to Ghana in 1969: “I was included in the American Forum, a group comprising founders from the African Studies movement,” she explained.

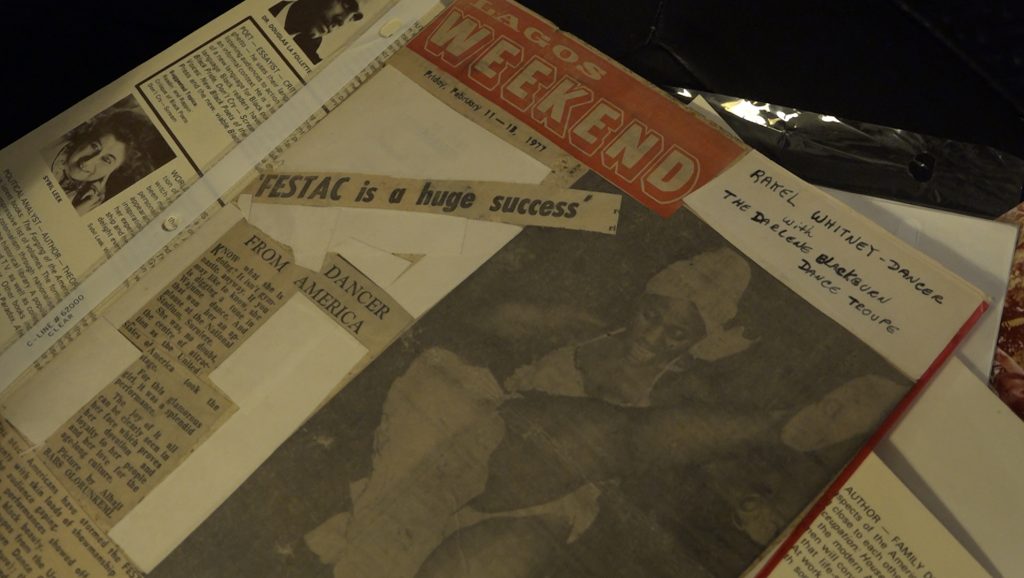

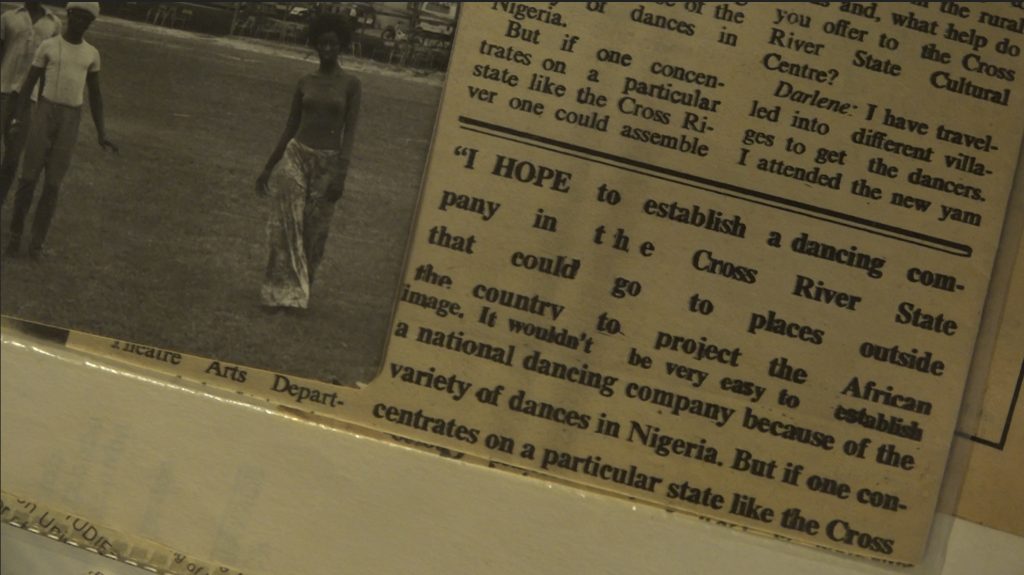

Starting in Ghana, Darlene set in motion a series of collaborations with African dancers and drummers that would guide her work and life for years to come, beginning with the Ghana Dance Ensemble. She returned throughout her career to West Africa, organizing dancers on both sides of the Atlantic, interfacing African dance history with the Black Arts Movement in Chicago. After Ghana, she traveled next to Nigeria in 1971, and then returned there in 1977 for the FESTAC festival on a bill that included luminaries like Miriam Makeba and Stevie Wonder. A few months after FESTAC, Darlene was invited back to Nigeria, spending three years in Cross River State, where she developed an influential dance program at the University of Calabar that continues through the present.

To document the overflow of images and histories Darlene shared with me, this essay includes selected still photos from the short film we created, which I have interspersed with longer-form oral histories from her. An array of publications have interviewed Ms. Blackburn across her long career, from Lagos newspapers to the History Makers Channel in Chicago. Artist and scholar Amira Millicent Davis is also writing a chapter about her influence on the Sun Drummers in the forthcoming anthology, Dancing on the Third Coast. I would like to thank Professor Crawford for inviting me to contribute to Fleeting Monuments, Brandon K. Calhoun for his work helping to edit Dancer of Time, and Tempestt Hazel for introducing this work to Sixty Inches from Center.

What follows is an excerpt from transcribed audio of Darlene Blackburn discussing her life and work with Wills Glasspiegel in her home on the South Side of Chicago.

* * *

I was born July 12, 1942, at home in the Morgan Park area of Chicago, and lived there until the family moved to Englewood. I got my start as a social dancer in Englewood when I was a teenager. I remember there was this young brother, we called him Poppa because he was smooth like an old man. He’s the one that took time with me and showed me how to groove into the music. If you danced with Poppa, you must could dance! I told him, “Teach me because I can have a party as soon as you teach me to dance.” My family had a really clean basement and I gave many parties as a kid, some great times, not realizing my family was just keeping me close by.

Everybody in our family could dance, that’s not no big deal. My mom didn’t want me to be a professional dancer because Black girls at that time were considered “exotic,” not concert dancers. But no big deal. Dance was something I loved doing. My first dance troupe started in 1963. I called them, “Those Who Want to Dance.”

At the time, I was working downtown at Illinois Bell Telephone Company. I would leave there and go to the library trying to find out more about Black dancers, and that’s how I started reading up on Katherine Dunham and all the things that she’d done, and I said, “I want to do that, too.” She definitely inspired me, and Pearl Primus, too. I was offered the opportunity later to be on scholarship at the Dunham School in New York, but I stayed in Chicago because of my job and the benefits I had at the telephone company.

I started out as a social dancer at a place called Budland—that’s where I used to win contests, on 64th and Cottage. Cottage Grove was known for all these awesome places. They had a place called the Persian Ballroom that was upstairs. People like Jackie Wilson would perform upstairs. And then downstairs in the basement was Budland. Basketball players that could really dance like Wilt Chamberlain, they would come there and dance with us. ‘Cause we could really dance. And they used to have this fellow named Gent. He just passed this year. He started with Don Cornelius [of Soul Train] in the studio here in Chicago. He was THE Dancer that inspired Soul Train. He would go down South and bring back all the different dances like “the uncle willy.” Of course he had his little clique and I was in it. Every summer, we’d be waiting to learn a new dance. He was what we would now call a “trendsetter.”

I danced down at Basin Street, a Latin place on Cottage Grove and 63rd. That’s where we did cha cha, mambo, merengue. Master Henry was down there playing the timbales and I was dancing to his rhythms. I was just dancing, and he said, “Look, you just what we looking for. I’m working with this band [Phil Cohran’s band] and they need an interpretive dancer. You need to come and audition.” I said, “I never danced nowhere like that. I’m just doing whatever I feel.” Henry said, “That’s what [Phil Cohran] wants. He wants someone to dance to his music. At least go to the audition.”

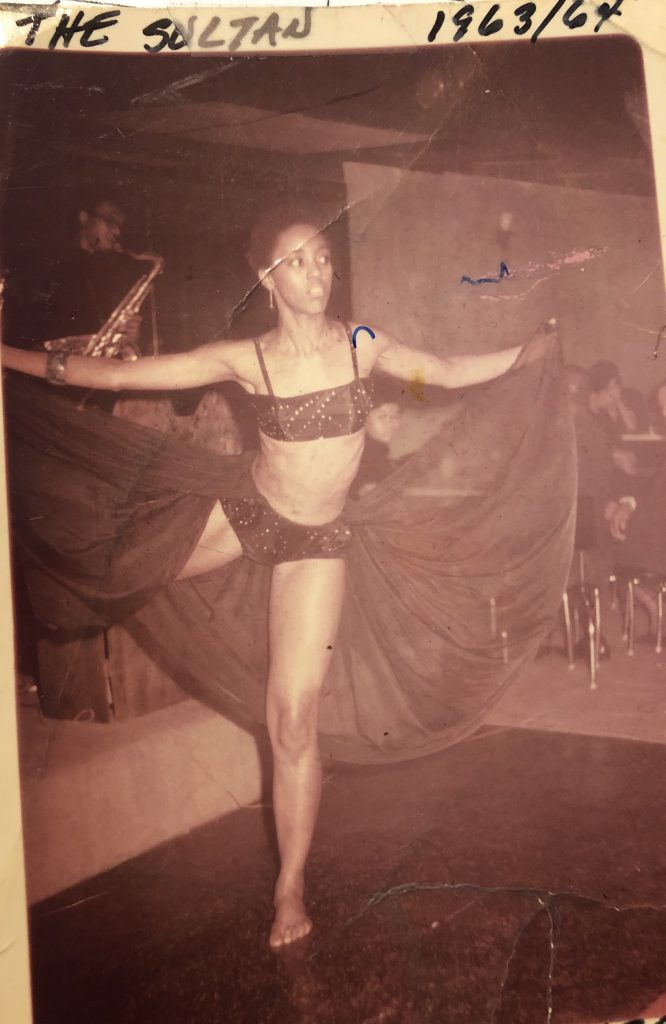

The audition was at his house. Phil said, “I want you to just listen to this music and I’ll be back and then you can show me what you can do to it.” So I listened to his music and then he came back. “Did you think of some things to do?” “Yes,” I said. After I danced, he said, “Okay, I’ll let you know.” Well, he called me back and I went into rehearsal at the Sultan club. I would just sit down on stage and anytime I felt like it, it was like being in church. His wife Delores [whose name later changed to Rael] made my costumes. She was a fashion designer and her work was superb. She made a lot of African fashions for ladies at that time. We did one song called the “African Look” where we would come out dressed in different African clothes to show the sisters how they should be dressing.

It all really jumped off in 1967 on the beach. That’s where we did Black Beauty. The dance was an interpretation of Black beauty, representing the Black woman. I did that in 1967 [pulls out an album cover]. That’s one of Phil Cohran’s albums [The Spanish Suite]. These are things I’m proud of. He thought enough of me to put me on one of his LPs and one of his CDs, too. That’s my lifetime mentor. No doubt about that.

I guess I was popular because I was never showing people, ‘‘Oh, I can dance.’’ I was trying to get all those Black people to get some pride in themselves. We was about pride. And I was trying to show all those Black girls: “Look at my hair, it’s short, and look at me, I’m dark.” I was trying to get them to relate to me. I remember being on the bus [in the 1960s] and I sat down with my little nappy hair and people would get up. They wasn’t too keen on looking at me. So my movement and my interpretation of Black Beauty was throwing it back to them. This is you. That’s what that dance was all about.

There wasn’t no ego involved in what I was doing. It was powerful because it was raw. Chicago is raw anyway. If they don’t like you, they throw things at you. I was glad they appreciated it. When you in front of your own, they think they can dance, too. When they appreciate what you do, that’s the best feeling. They got that attitude of: “Lemme see what you can do.” You had to be courageous. I didn’t have a stage. I was on that cement dancing. No stage uplifting. I had to dance around them, eye contact—you had to be courageous, not looking at the floor or the ground.

Phil Cohran was the one who told me I was on The Wall [in 1968]. I couldn’t even believe it myself. He was glad I was on there. But I think he was hurt that he wasn’t on there and I was hurt for him cause I could feel it. He had done so many free performances. He played for the people. He didn’t play for who asked him to play there. He was always for the people. Everything he did, he would tell me this is for the people. He didn’t tell me what to do. He would tell me what his compositions meant, and I would try to express it as much as I could. I was just trying to express his composition. Roy Lewis took the picture of me on The Wall. He caught me dancing at one of Brother Phil’s performances. In that pose from my picture on The Wall, I’m doing one of Phil Cohran’s dances. The music is called Cephus. So I’m dancing to this tune of his, but he’s not on there.

Phil was very outspoken. A lot of people didn’t like what he had to say. Not just whites—Blacks, too. He wasn’t in with the clique. Cause you know Chicago is a clique. Let’s deal with the reality of that. So he wasn’t in with the clique. He performed around town just like I did. They just didn’t take no pictures of him cause he wasn’t in the clique. Why? Because he was very outspoken. He would say people weren’t doing as much as they could do. He had done so much sacrifice for the community and the clique didn’t want to recognize him. We had a mobile unit that went to all the project areas, which was good. Ida B. Wells, Robert Taylor, Stateway Gardens, 12th Street. In the morning we would teach dance and in the evening we would host a performance.

Dr. Margaret Burroughs is my second inspiration and my mentor because she said to me, “Girl, you need to go to Africa.” She was still teaching at DuSable High School. That’s where we met and when she saw me dance, she said, “Oh, where did you learn those dances from?” I said, “Oh, these are dances I made up,” and she said, “Oh, well you need to go to Africa if you could make up dances like that, ’cause I done seen those dance movements.” I said, “Sure, I would like to go, but what do that mean?” She talking about, “need to go.” I don’t have no money. I‘m just a young struggling artist. She said, “You have to want to go.” I said, “Well, I want to go.” She said, “Well, then we gonna see about you going. Because I got a group that’s going this summer and if you believe you want to go, you will go. You just have to do affirmations.” I didn’t even know what the word “affirmations” meant. She started me doing affirmations. And it did come true.

I think that she would have liked to have been a dancer. She was just like Maya Angelou. You know Maya Angelou was a dancer? She loved dancing and so did Dr. Burroughs. She did everything she did from her heart. She would just give her pictures away and sign it. She gave so much. She would come do performances and bring all her African garb and dress the kids up. I thought that was so wonderful. She would come for nothing. Just for those kids to put on those clothes. She went to Ethiopia a lot and had a lot of Ethiopian garb. She definitely inspired me when she came to my class. I was teaching at Calumet High School and she came for Black History month, dressed up the students and we had an African fashion show.

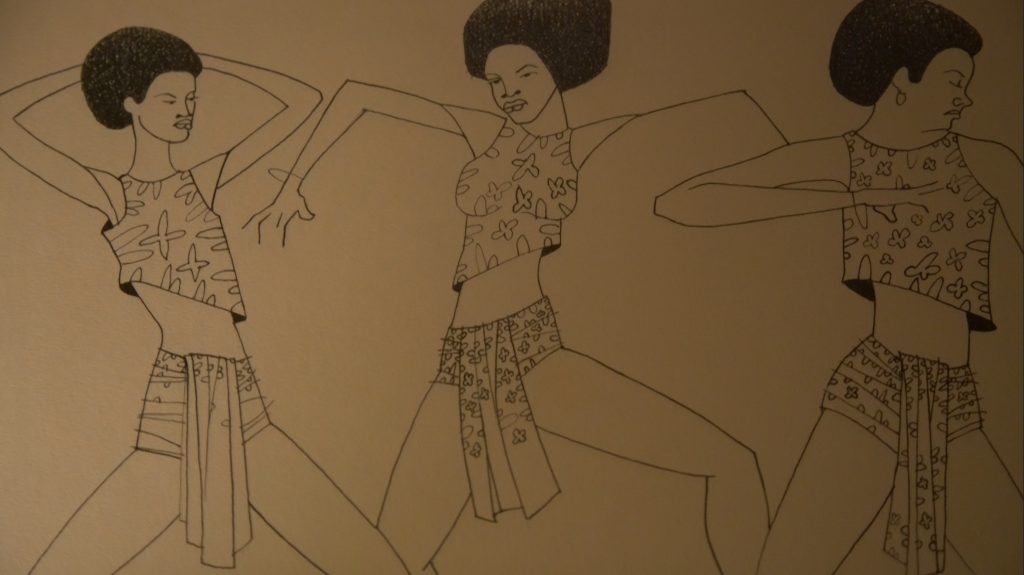

In 1969, I started doing a number called Africa to America. Every time I do it, I change the social dances of America, but I never change the traditional African dances. I just ask the kids [in Chicago], “What does this African dance look like?” I let them see the African movement and they’ll show me what social dance looks close to that. That went over really big; showing the comparison, that’s the whole idea.

The Pharaohs [a band that included former members of the Artistic Heritage Ensemble] were superb. They could play anything. It was really deep then. They were playing for lots of different artists. So I would say, “I want some music that looks like Uncle Willy,” and they would know the music that would go to Uncle Willy [one of the dances Gent brought to Chicago from the South] and they could play it eight bars, and then that eight bars would freeze while we transitioned to our African movements. Now we doing the African movement, then they would freeze after eight bars of Africa and come back in with African American sounds and movements, locking and other social dances of the day. It was a competition. I also did it in Nigeria. I did it with my dance troupe there, and they would compete. They would always say, “Why America gotta be last on stage?” Africa would do they movement, then here come the moonwalk, and they said, “Why can’t we be last?” I said, “Because y’all first, understand that!” They wanted to be last on stage. You can’t be last, you’re first, but it was a competition thing of everybody going back and forth from Africa to America. I have all that stuff on tapes, VHS.

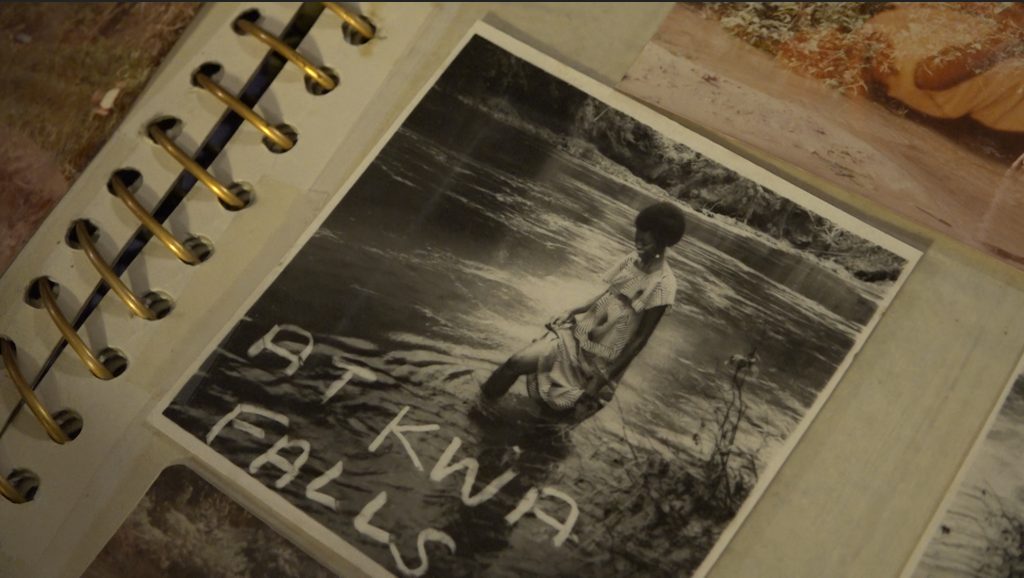

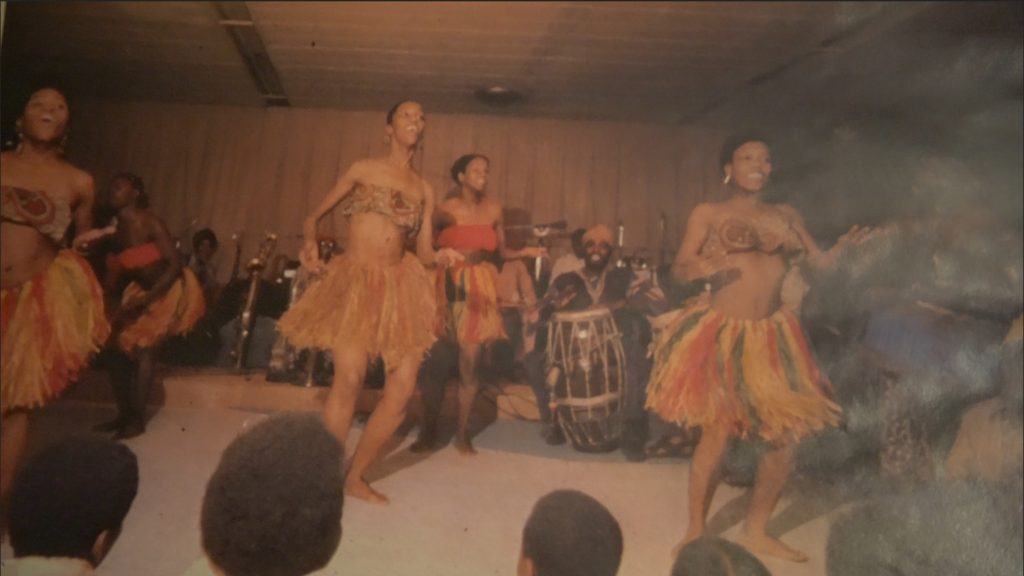

That’s me in 1969 at the University of Legon [pointing to photograph above], and this is Victor from the Ghana Dance Ensemble. Just enjoying what you’re doing. That’s the key. I was a social dancer before all of this. That social dancing is where I made up my so-called African movement.

When I got to Africa, I saw the Ghana Dance Ensemble was practicing. I’ll never forget this sister named Grace. She was doing African highlife and then she started doing what looked like “the mashed potato” and I said, “Oh girl, I could do that.” And I just jumped on stage right with her. She couldn’t believe it either. So I was in after that, you know that, I was in. A lot of times when I was in Africa, I could just feel the rhythms and I could just do the dance. No one taught me, I just jumped up there, I could do it. I came up in social dancing, I won contests, lots of them.

My first trip to Africa? It was like a dream come true. I wanted to kiss the earth, walk barefoot. They said, “Put on some shoes, you don’t used to this, get fungus and all that.” I wanted to be as native as possible, they said “You can’t do any of that.” Like when I went to the Kente cloth village in Kumasi—I went to where they make the Kente cloth. I was on the bus thinking, am I dreaming? Is this really a village? Do they really have all this cloth trying to get you to buy it for nothing?

That was in 1969, when they were just getting ready to start the African American Studies programs. So it was a group of American teachers and historians who were there in Ghana to study and discuss history. They weren’t into dancing like I was. They let me go off and do my own thing. So I hooked up right away with the Ghana Dance Ensemble because they were practicing out of University of Legon there. I would go into the villages ’cause that’s where the ensemble would learn the dances. They didn’t know them either. They would go into the villages to learn the dances from the traditional people and I would go with them.

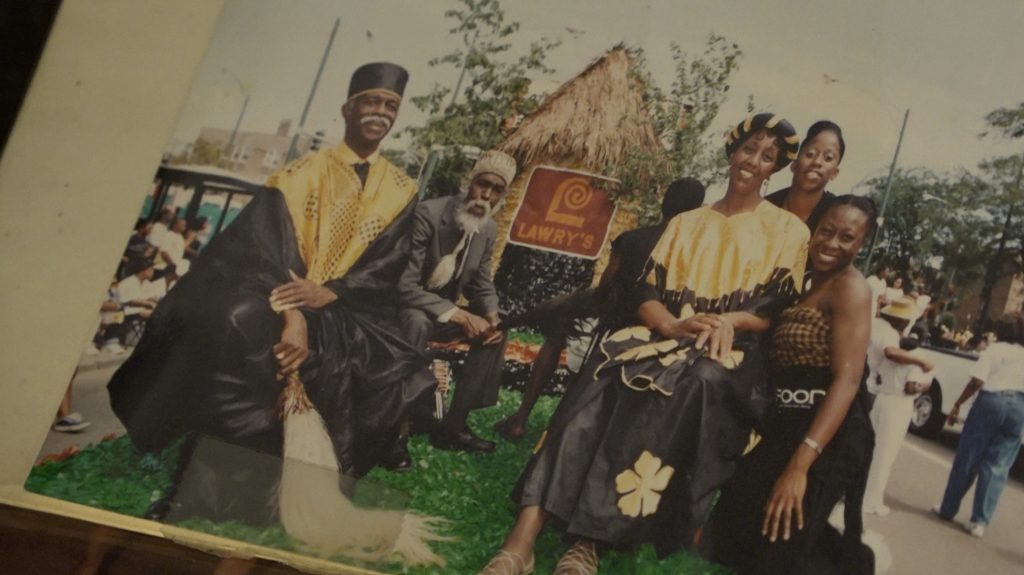

In 1971, we raised the money to take eight dancers and two drummers to Nigeria, West Africa. I had help fundraising from giant Chicago names like Oscar Brown Jr. and Jean Pace. Herb Kent and Yvonne Daniels were commentators at our events. Nigerians in Chicago hooked us up with this club in Nigeria to perform for about two weeks. People came to our show. That’s when we met Fela Kuti. He just liked to watch us social dance. It wasn’t no big deal to me. I wasn’t even aware of how important Fela was. Here’s Fela taking us back and forth to his Shrine. I’m just thinking he’s a regular guy being nice in Nigeria. Life is unbelievable.

In 1977, we were chosen to travel to FESTAC in Lagos, Nigeria, along with Julian Swayne’s Inner City Dancers. We performed at the festival, and we also performed at Fela’s shrine. Fela had been barred from the festival, but I didn’t know he was barred, I just knew we owed him after he had been nice to us in 1971. So we performed at the Shrine and Roy Lewis took photographs. Later that same year, I was invited back to Nigeria to be artist-in-residence at the University of Calabar in the Theater Department, to teach movement for actors, and to start a Calabar Dance Company. I stayed for three years. I didn’t start the company right away. It took a whole year because I went from village to village to bring all these dancers together, following the same protocol I developed in Ghana. And then I taught them modern dance, too. I had a television show there in Calabar. That’s them doing “Young Gifted and Black” [pulls out a picture]. All of them are Nigerian.

Later on, I taught at Calumet High School in Chicago for 18 years before it became a charter school. I loved every minute of it, and I would count my blessings every morning that I could go to school and teach what I love. I started a dance troupe at Calumet where I had male dancers that were in gangs. I didn’t even know they was in gangs. They would jump up on the stage dancing. All these kids would start screaming and hollering and cheering. And then they said to me, “You have the leader of the gang up on stage.” I said, “Oh no,” but hey, it’s better to have them dancing. That’s my point. A lot of times they would tell me, “I can’t believe you got them doing what you asking them to do.” ‘Cause some of them were dancers. They loved to dance. A lot of them tell me that they still alive because they was dancing and not in them streets, countless times I done heard that. I know that dancing works.

Now I’m teaching at the Englewood Senior Center and it’s a circle of coming back. I’ve got dancers who were with me in 1963, dancers who were with me in the 70s, 80s, 90s. When I stopped dancing, they were like, “You could at least have one class.” I was like, “My knees are too bad.” They were like, “Just teach one class.” That class used to be at 8:30 in the morning and they were all there. Then I got a job teaching yoga at 9 am. Chair yoga. I teach there everyday at Humana. They love to dance. Enjoyment. That is my whole point. I’ll turn 80 soon. Keep it moving, it has no age on it. All of them are in their 70s. That’s the idea. Keep it moving. Don’t never stop moving ‘till it’s over. It ain’t over ‘till it’s over.

Regarding technique, you need good technique so you can survive. Don’t end up like Pearl Primus and Katherine Dunham with bad knees where you can’t walk. So, good technique—nothing wrong with good technique. That’s why I took from [dancers] Maggie Kast and Neville Black. I took contemporary dance from them. It really did help me as I got older. I took classes from [Chicago dancers] Homer Bryant and Joel Hall. All of that saved me, allowed me to keep walking—my age group, not too many are walking good. If you’ve got good technique, you can almost do any form of dance. I studied with Lucille Ellis and Tommy Gomez. I studied Dunham technique, a lot of body rolls, contractions and releasing of the body. When I was in New York, I studied Horton technique, which Alvin Ailey used. I studied with James Truitt and Thelma Hill from Alvin Ailey. Horton technique deals with the parallel line, contractions and release. Technique really helps people with African dance, interpretive dance, whatever dance you wanna do.

I think that young people today really, really need help and guidance. When I started my dance troupe at the Englewood Urban Progress Center at 64th and Green [on the South Side of Chicago] in the 1980s, that was a grant. I was working there teaching dancing. Then the director there said, “Why don’t you start an apprentice program? You can have young teenagers teach pre-teens. Kids learning how to be teachers.” That was superb and I got good dancers out of there because they were practicing everyday. I would even take them down to Jimmy Payne and Neville Black dances. I would let them sit in on studio classes. That’s my thing, each one, teach one. Pass it on. If it’s gonna be a grant, it’s not just funding people to do a performance. That’s not enough. Teach someone and you’re passing information on, that’s what I’m into. I’m using dance as a vehicle. I’ve always used it as a vehicle. You can ask anyone who studied under me, they learn more than dancing. They learn how to act. My people’s got degrees ‘cause I taught them that you gotta make it out here. I got degrees. I taught and still teach that.

Regarding racism and sexism in my past, I faced it, but I was brought up with such power. I can just say it, no other way. Just a lot of power. I brushed it off. I was just told, Black is beautiful, So I would do things when we were at different universities. I would go in the washroom, take my pick out [picks hair]. I never allowed it to stop me. I’ll never forget one time we was at the Natural History museum downtown in Chicago. I had my little African garb on, raw silk and all that. And a little girl saw me prancing around. A little Caucasian girl, and she asked her father, “Why is she acting so grand?” I was paying attention and her father told her, “Oh, she just likes herself. That’s all.” And that was just the truth. I had been brought up to like myself. I really feel good about that. My family raised me that way. They liked me. I was the only child for a long time. Fourteen years between me and my brother. I was raised to like myself, stand up tall and be proud.

Darlene Blackburn continues to live, teach, and dance from her base on the South Side of Chicago. Since the 1960s, she has influenced the history of American and African dance in profound ways, spreading knowledge and the love of African dance in America. Her students have gone on to dance with the Harlem Ballet and Alvin Ailey. Here in Chicago, Blackburn’s work has inspired the African dance community. Both Joseph Holmes and Alyo Tolbert started with Darlene Blackburn before co-founding their own companies, Joseph Holmes Dance Theater and Muntu Dance Theater. Here is a recent video of Darlene Blackburn teaching African dance to the Chicago Humanities Festival in 2021, “keeping it moving” in theory and practice: https://vimeo.com/641326466/f48fafbcf7

Wills Glasspiegel is a filmmaker, scholar and organizer from Chicago. He recently directed Footnotes, a large-scale video projection for Art on theMART in Chicago, dubbed 2021’s “public art of the year,” (Time Out), “dance moment of the year,” (Chicago Tribune) and “pop music moment of the year” (Chicago Tribune). He co-directs Open the Circle, a nonprofit focused on Chicago footwork and education. Wills is a PhD candidate in African American Studies and American Studies at Yale University.