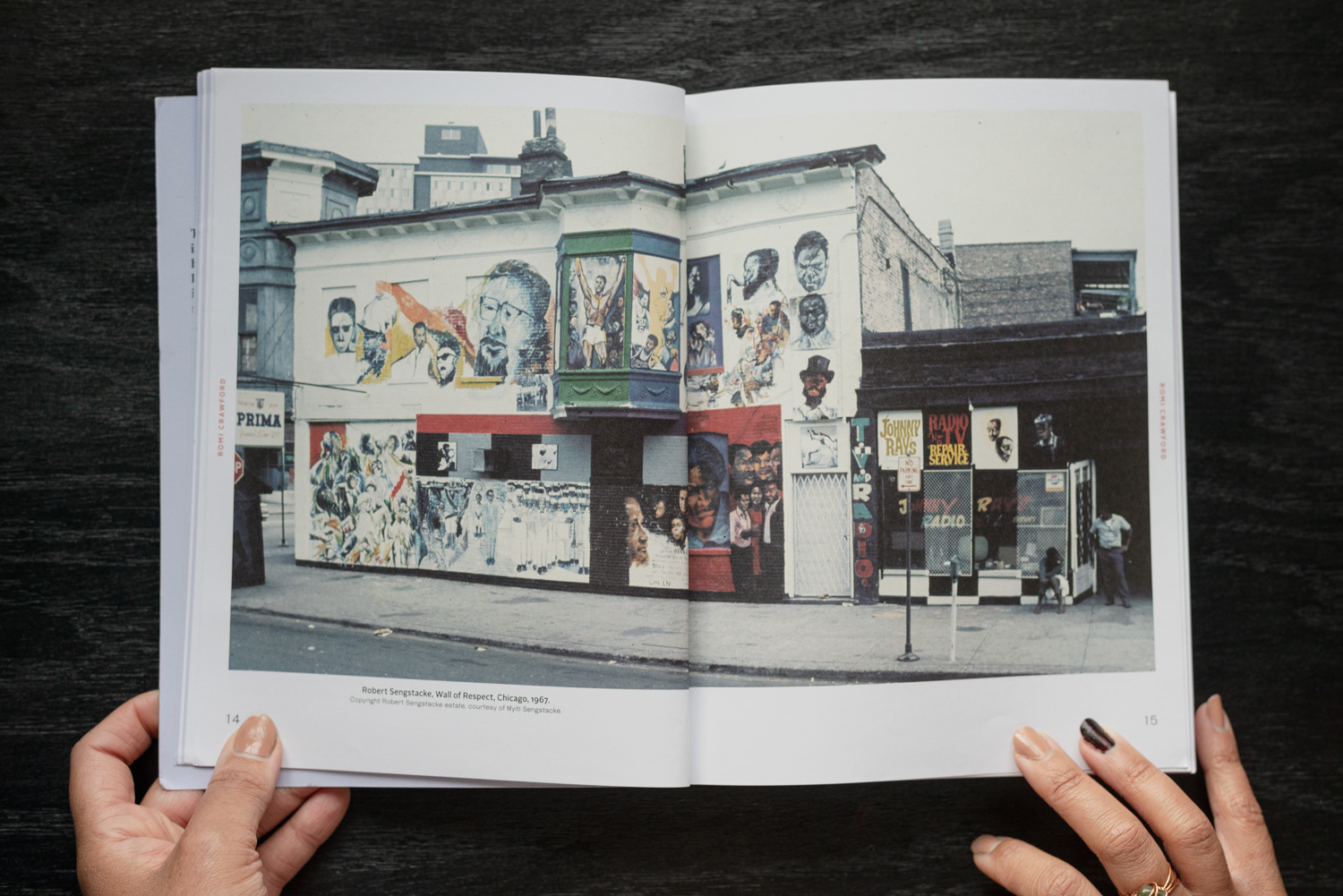

Featured image: The book Fleeting Monuments for the Wall of Respect is open to pages 14 and 15, showing a 1967 photo by Robert Sengstacke of The Wall of Respect in Chicago. You see a street-level view of a mural composed of over a dozen portraits of historic figures painted on the side of a two-story building. Photo by Ryan Edmund Thiel.

This article is presented in conjunction with Art Design Chicago Now, an initiative funded by the Terra Foundation for American Art that amplifies the voices of Chicago’s diverse creatives, past and present, and explores the essential role they play in shaping the now.

This review coincided with the event “Revisiting the Wall of Respect and the Black Arts Movement” that was presented by Chicago Humanities Festival and took place at Blanc Gallery on October 2, 2021, where Romi Crawford, Darlene Blackburn, Thabiti Lewis, and Robert E. Paige, who are each historians of or artists from the Black Arts Movement, led a reading and interactive session followed by the Chicago debut of BAM!, a documentary reflecting on the international influence of the movement.

Fleeting Monuments for the Wall of Respect is a 300-page meditation and offering. It is an expansive delineation in book form composed by editor and art historian Romi Crawford as an homage for the Wall of Respect, a legendary mural that has loomed large in the collective cultural memory of Chicago’s South Side since it was created at the corner of Langley Avenue and 43rd Street in 1967. Painted by members of the Visual Arts Workshop of the Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC), The Wall of Respect was a site and enduring symbol of the Black Arts Movement. Before it was destroyed in 1971 due to a fire, the wall made a mark on public art by signaling a turning point into a distinct era of mural-making and by becoming a site and destination of groundbreaking multidisciplinary artistic production.

Calling it a wall is somewhat of a misnomer. Although the most widely circulated visual documentation of the wall depicts it as a shapeshifting mural with many artists collaging it with words, paintings, and photographs over its years, the memories and oral histories that have been carried forward after the building was demolished let us know that it was much more than a canvas for a mural. It was a stage and a rallying point. It was a celebration and articulation of liberatory and radically imaginative agendas and expressions. It was, and is, a provocation and a source for memory and material. It is one of the many legacies that can be tapped into when artists, particularly Black artists, want to be reminded of the artistic strategies and methodologies that are available to (re)activate within a contemporary context, as our current times hold many of the same social and political grievances and also the markers of a cultural renaissance and golden era.

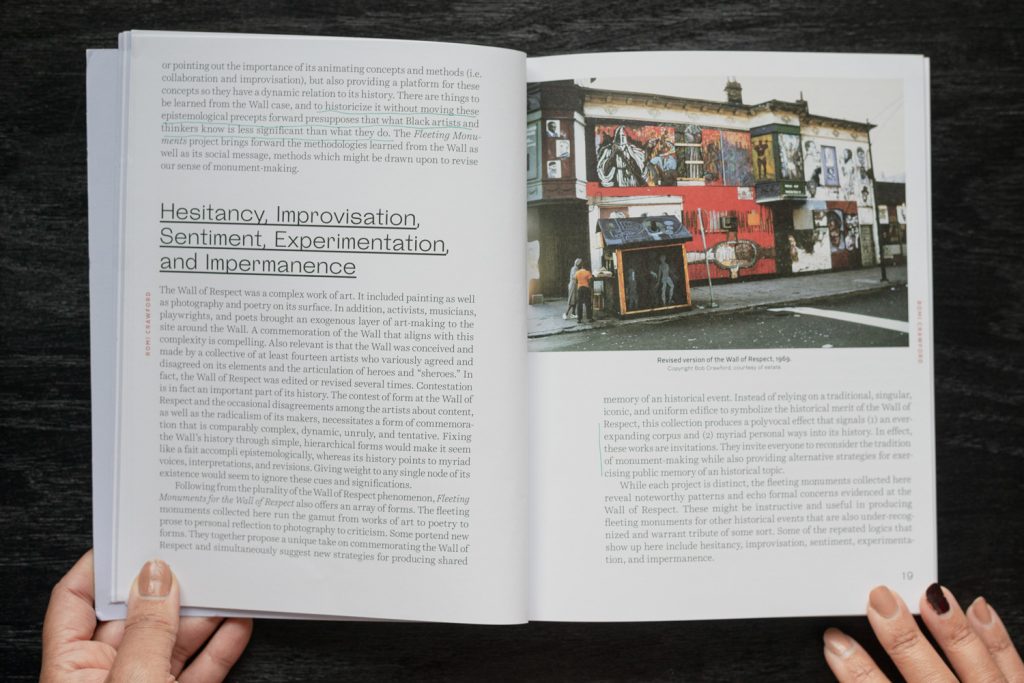

Each contribution to the book is anchored by the concept of a fleeting monument, defined by Crawford as a new form of monument making that gives an expansive view for how we articulate “spaces, events, and scenarios that are underdiscussed or erased historically, that might warrant marking, but in a manner that is less than monumental, that is in some way anti-heroic, unstatic, and in no way timeless.” Crawford goes on to say, “in effect, Fleeting Monuments for the Wall of Respect offers a retort to the current monument fever, addressing the problem of monuments by amplifying an alternative history of praiseworthy sites and subjects.”

Using something that no longer exists in physical form as a jumping off point, Fleeting Monuments acts as a complementary text for and documented evidence of how artists and organizers are carrying the essence and energies of the Wall of Respect into today. The book provides examples of how artists are harnessing ephemeral and time-based tactics to disrupt the ways that failing systems and destructive histories have been celebrated on city streets, in public parks, and in the pages of our (text)books. It is a companion piece for the ongoing and recent efforts to revise and interrogate the integrity of United States history as told through the public statues, commemorative symbols, and memories that linger, lurch, or are absent throughout the country. And yet it is also a call to make more visible an approach to commemoration that honors life, joy, and our unbreakable bonds with one another.

By expanding the modes of memorializing, Crawford asks us all to interrogate the hierarchies and value systems that have historically dictated what becomes worthy of commemoration. She reveals the methodologies, especially those of non-white artists and practitioners, that have learned, practiced, and carried this expanded view for generations, passed on by and through those who came before us.

A copy of this book should and, arguably, will be included in the repositories that speak to the depths of our current period of physically, intellectually, and unapologetically dismantling the sea of problematic symbols of genocide and oppression beyond the reactionary, institutional, and seemingly earnest efforts such as the Chicago Monuments Project, The Monuments Project, or Monument Lab. Fleeting Monuments will sit somewhere among the memories and materials that hold remembrances of catalytic moments that sparked a wave of institutional efforts—moments like the #DecolonizeZhigaagoong solidarity rallies organized in the summer of 2020, as well as the rallies organized by Chi-Nations Youth Council, Black Lives Matter Chicago, Good Kids Mad City, Brave Space Alliance, ChiResists, and others—all of which led to the overdue removal of the Christopher Columbus statue in Chicago’s Grant Park. Or the West Side students of Village Leadership Academy who have been working since 2016, when they were in 5th grade, to get the City of Chicago and the Chicago Park District to change the name of Douglas Park in North Lawndale—a park originally named after slavery advocate Stephen Douglas—to Douglass Park, named after abolitionists Anna Murray-Douglass and Frederick Douglass. These brilliant young people have been doing this work since before what Crawford rightly calls the “current monument fever.”

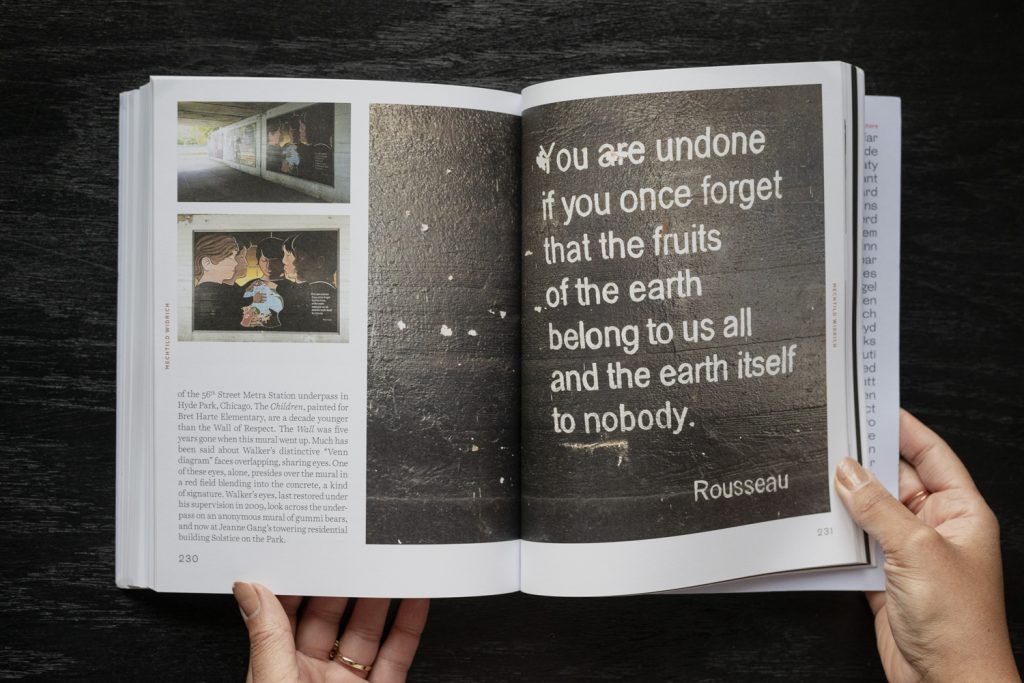

It must also be stated that through the concept of the fleeting monument, what Crawford is proposing are the kinds of public markers that are better representatives of us as complete people, as a constantly shifting society that is growing, changing, and learning all the time. We are all flawed, full human beings. And the people we have historically looked to as worthy of commemoration are often presented and positioned in ways that shrink their (and our collective) complexity. Fleeting monuments instead offer containers that embrace complexity and evolution.

This book is posing so many questions. How do we define collective memory and what things are held there? Who is part of the collective that we hope are holding these memories and carrying them forward? How do we know something has successfully moved into a collective consciousness, making it ripe for collective remembering? Is this book a monument? How does this book get us closer to articulating more clearly what preservation and memory work mean, and the shifting limits and limitlessness that history-keeping as a practice holds?

* * *

My gut is telling me that reviewing a book like Fleeting Monuments for the Wall of Respect isn’t the way I’d like to contribute to this moment and the histories it’s entangled in. Instead of a attempting to synthesize something immeasurable through a review, I want to show my reverence for The Wall of Respect and everyone who knowingly or unknowingly has and will include it in their creative, scholarly, and tactical bibliographies, starting with the artists, historians, and writers featured in the pages. I want to be another entry point, a conduit for you and these fleeting gestures.

My response to the book is made up of a series of visual excerpts organized according to the book’s five sections and is composed of pages directly from the book that pull from the words and works of Crawford and a handful of the thirty-three artists featured. The book pulls together a wide range of mediums into its pages—performance, dance, sculpture, sound, education, poetry, photography, graffiti, graphic design—so this response will, too, be multimedia in form.

I. Legacy Monuments

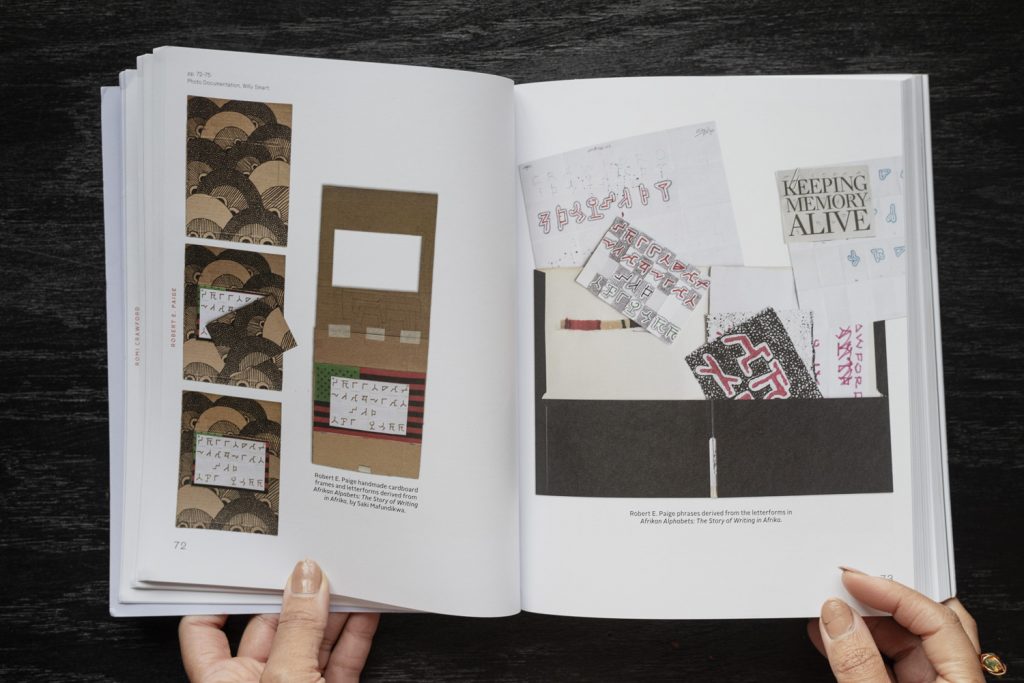

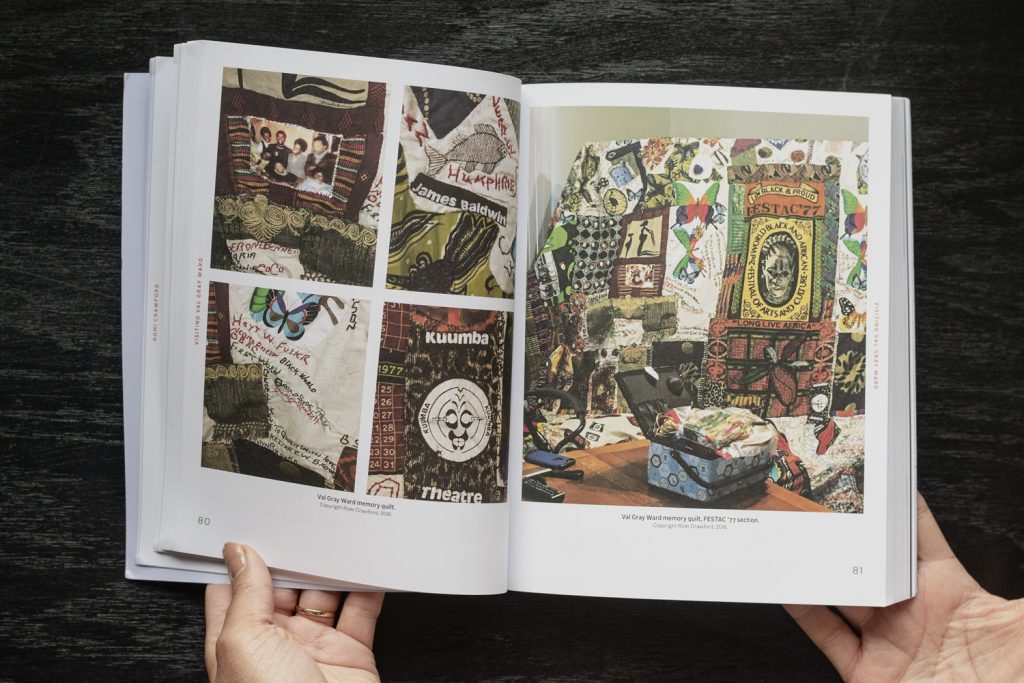

In “Legacy Monuments,” the first section of the book, Crawford has assembled artists, performers, and writers who have firsthand knowledge and experience of The Wall of Respect in its short five year lifespan. Abdul Alkalimat, Darryl Cowherd, K. Kofi Moyo, Haki Madhubuti, Robert E. Paige, and Val Gray Ward are each a grounding force and frame, providing the fertile energy and original philosophy from which all other artists in this book are drawing.

II. Gift Monuments

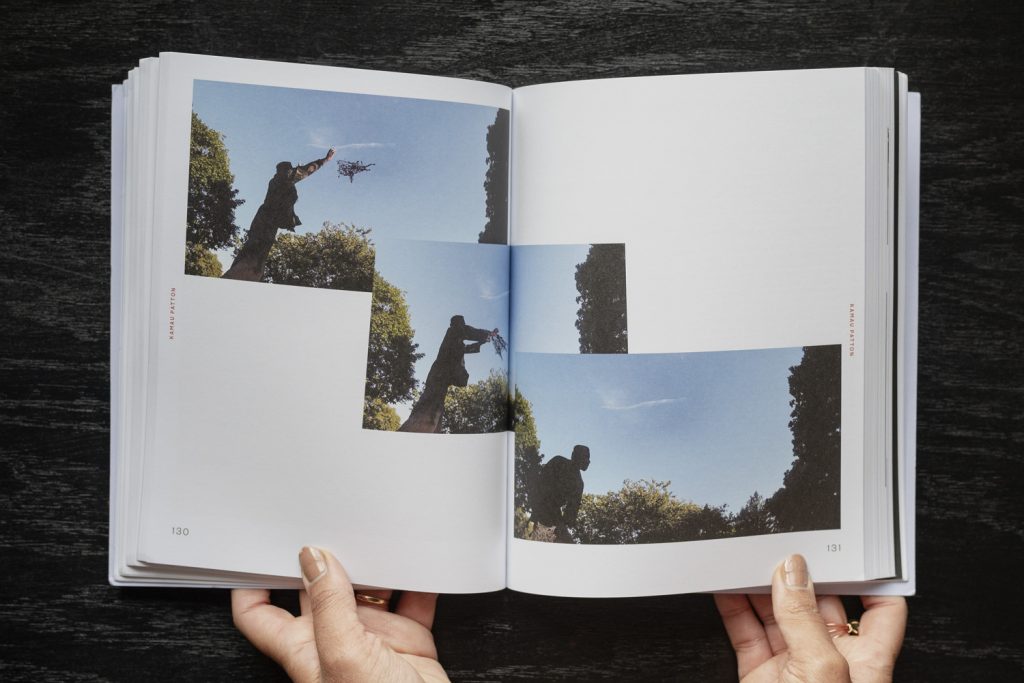

One of the many enduring Wall of Respect philosophies is that of collective, community, and artistic generosity, an idea carried forward by artists Miguel Aguilar, Bethany Collins, Julio Finn, Maria Gaspar, Wills Glasspiegel, Naeem Mohaiemen, Kamau Patton, and Rohan Ayinde in section two, which is titled “Gift Monuments.” As Crawford describes, these works “reveal a willingness to pay homage and memorialize through gifting, precedented by The Wall of Respect itself, but reflected here too on the part of all of the contributing artists and writers who share, give, and/or reproduce their work in a context of speculative and generative collaboration, not knowing what the cumulative outcomes might be.”

III. Reflective Monuments

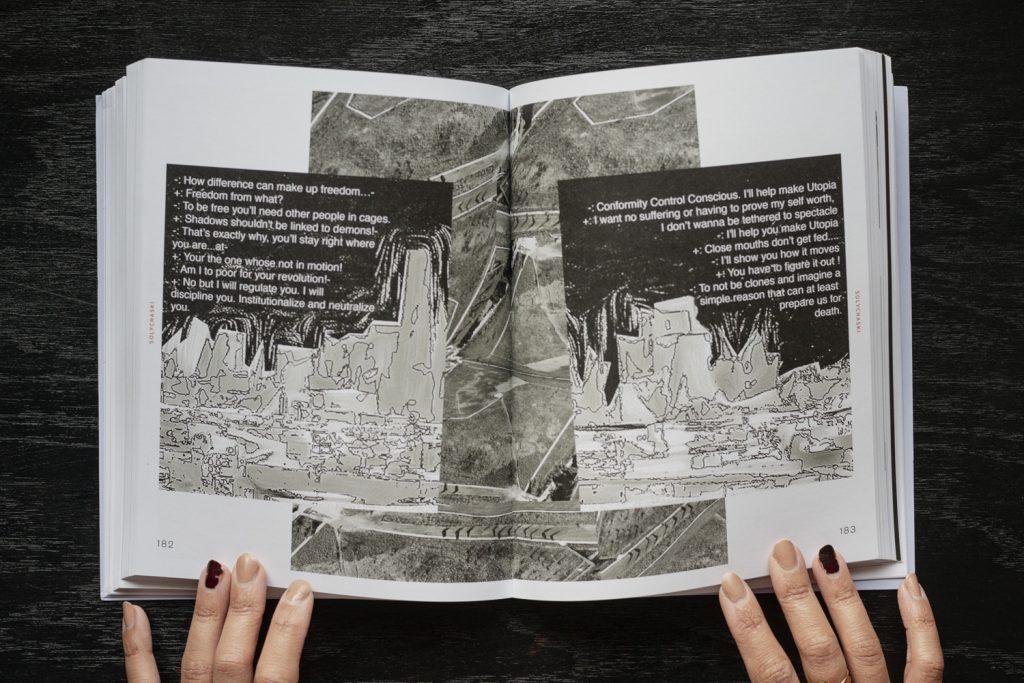

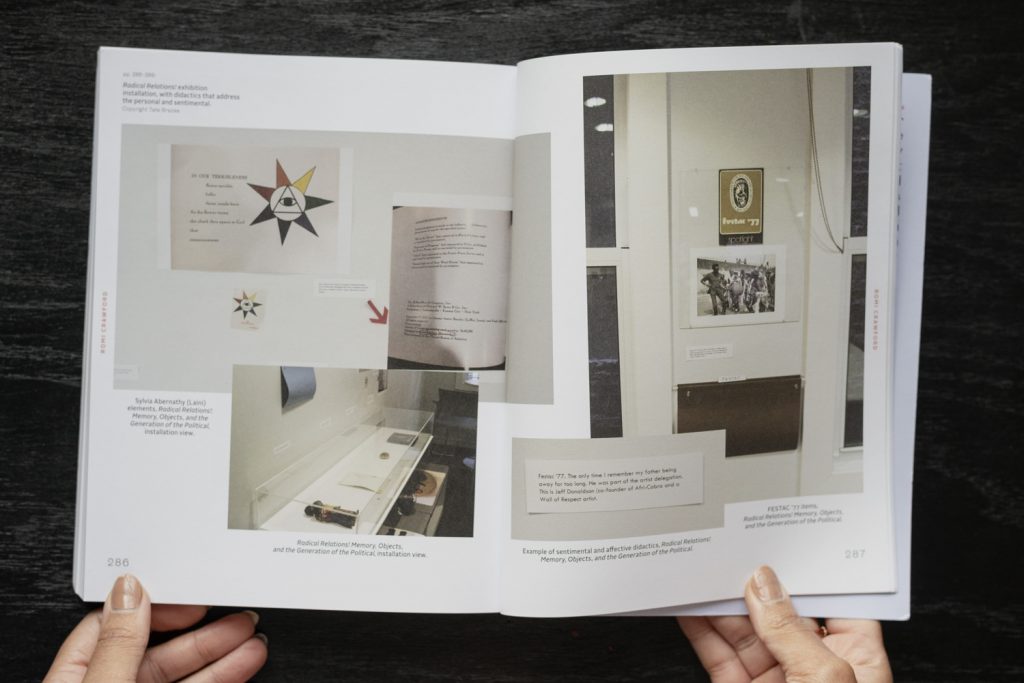

How does something so temporary and fleeting, something that anyone born after 1972 can only have indirect memory of, continue to supply generative material nearly half a century later? Rather than revealing a series of discrete works, the artists featured in the “Reflective Monuments” section give a glimpse into their process and reveal how their entire practices are woven with the material or principle threads of The Wall of Respect as a site, as well as the virtues of the artists who activated it. D. Denenge Duyst-Akpem, Stephanie Koch, Stefano Harney and Fred Moton, Nicole Mitchell Gantt, Cauleen Smith, solYchaski, Norman Teague, and Bernard Williams are, as Crawford describes it, chipping away at “prevailing disciplines, practices, and histories while signaling dynamic and fruitful outcomes from their critical/reflective endeavors.” I truly believe that the act of chipping away and constantly (re)evaluating the frameworks and histories that we’ve been taught and told is essential when thinking of the future monuments that are capable of holding the full complexities of any community or people—reinforcing Crawford’s assertion that commemoration can and must be so much more than a static object. Instead, they can be performative, transitory, and a continual work in progress.

IV. Make and Do Monuments

Although each of these sections are charged with qualities that are quintessential characteristics of not only The Wall of Respect, but also Chicago, in the fourth section, titled “Make and Do Monuments,” Crawford illuminates the levels of intimacy and the spirit of self-determination that are woven into the practices and actions of this city’s artists and people. Wisdom Baty, Kelly Lloyd, Damon Locks, Mechtild Widrich, and Jefferson Pinder are handling what Crawford describes as “acts of memorialization that are micro, personal, domestic, local, and physical.” These artists are bringing private thoughts and personal experience into public spaces, and provoking people—often strangers, new friends, and future chosen family—to do the same.

V. Remnant Monuments

The book ends with “Remnant Monuments,” focusing on works that point to the traces and residue of The Wall of Respect and related histories, as well as the ways we accept, reconsider, commemorate, or attempt to fill the vacancies that life, systems, and time often leave behind. Crawford said it best when she wrote, “such monuments made from what’s leftover are important for their reference back to the historical occasion’s failed project—of social and racial equality, evidenced here by the emptiness of the Cabrini-Green and The Wall of Respect sites.” Faheem Majeed, Jan Tichy, Mark Blanchard, Theaster Gates, Romi Crawford, and Lauren Berlant close out the book with an open-ended question and an ellipses that, like The Wall of Respect, doesn’t signify an ending, but rather an open and revolving doorway from which so much more can and will come.

____

Endnote:

Fleeting Monuments for the Wall of Respect was released in May 2021. It was edited by Romi Crawford, published by Green Lantern Press, and distributed by University of Minnesota Press. It is currently available for purchase at www.upress.umn.edu. Contributors to the book include: Miguel Aguilar, Abdul Alkalimat and the Amus Mor Project, Wisdom Baty, Lauren Berlant, Mark Blanchard, Bethany Collins, Darryl Cowherd, D. Denenge Duyst-Akpem, Julio Finn, Maria Gaspar, Theaster Gates, Wills Glasspiegel, Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, Stephanie Koch, Kelly Lloyd, Damon Locks, Haki Madhubuti, Faheem Majeed, Nicole Mitchell Gantt, Naeem Mohaiemen, K. Kofi Moyo, Robert E. Paige, Kamau Patton, Jefferson Pinder, Cauleen Smith, Rohan Ayinde, solYchaski, Norman Teague, Jan Tichy, Val Gray Ward, Mechtild Widrich, and Bernard Williams.

Tempestt Hazel is a curator, writer, artist advocate, and co-founder of Sixty Inches From Center. Find more of her work at tempestthazel.com. Photo by Matt Austin.

Related:

Darlene Blackburn, Dancer of Time

Wills Glasspiegel expands upon his short film, Dancer of Time, with further discussion, imagery, and extended commentary from Darlene Blackburn.