“Collector’s Corner” looks at the artistic, curatorial, and cultural forces behind the act of collecting. We visit the homes, businesses, garages, desks, and closets of artists and cultural producers who thrive from this occasionally unruly practice. For this installment, we talk to Dana Mees-Athuring at her residence in Logan Square about her collection of 1930s memorabilia, Chicago history, and the politics of femininity and design.

Dana Mees-Athuring is a woman who communicates through many means: plants, bread recipes, garage sales. She is one of the first neighbors that I befriended after I moved to Chicago two years ago. Throughout the time I have known her, her stories and interests have become an inextricable element to my conception of what this city invites and celebrates. A Chicago native, Dana has had every kind of job that is near or distant to art throughout the city’s dynamic history.

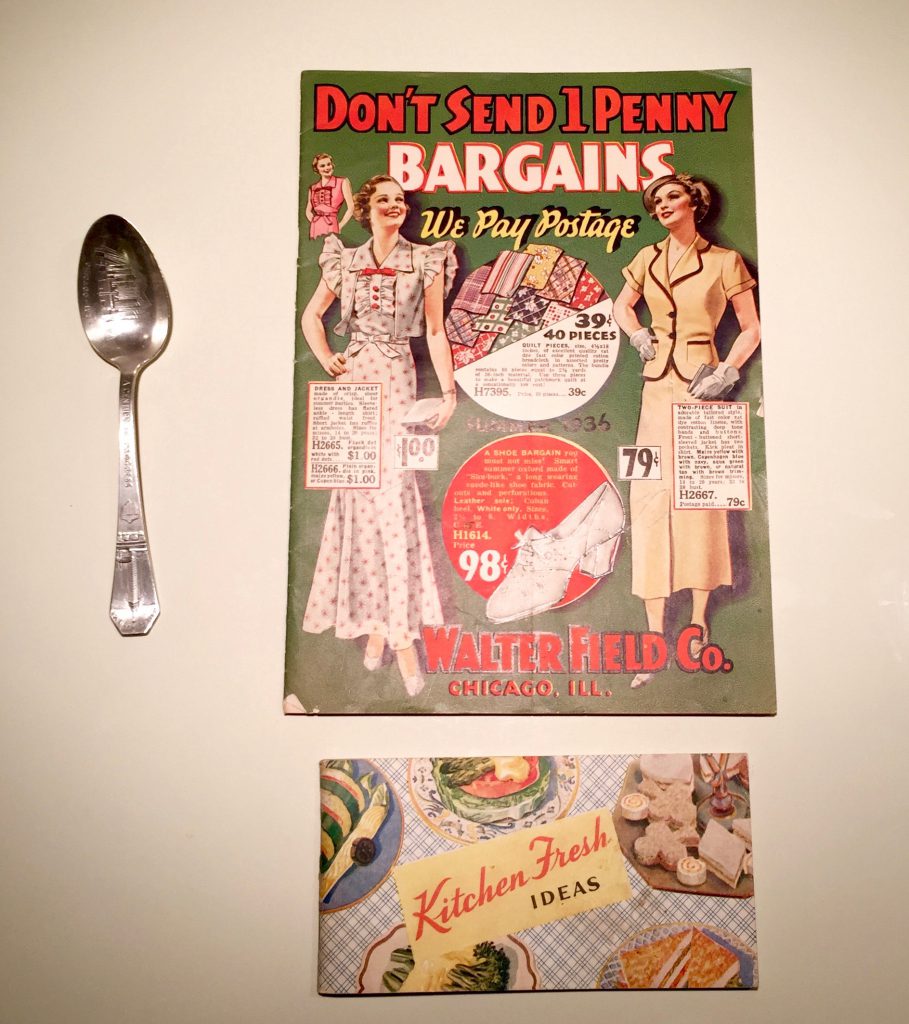

Her house is a galleria of vintage and rare treasures from the many eras that she celebrates and honors through her collections of art, books, household items, ephemera, and more. Something that always intrigued me while having conversations with Dana was her penchant for the 1930s. I had not really met anyone before who knew so much about how that era’s material culture functioned and how it could be regarded— it’s not the kind of material that’s necessarily spotlighted in vintage stores. I asked Dana to pick several items from her varying collections that all centered around this period to see what hooks her to the time of talkies and tinctures.

People often regard the successes of the ‘30s as a blueprint for ideas that this country can remix to solve the economic and social issues of today. In Chicago specifically, the World’s Fair set a tone of curiosity that still lives in the city.

“My grandmother, my grandfather, my father, and all of his siblings went to the fair and nobody else wanted [this souvenir]” tells Mees-Athuring. The family’s perception of banality towards the fair prompts the question of the worthiness of collecting the spoon. Would the spoon be more valuable if the family regarded it as such, or is the fact that it is from the 1933 World’s Fair enough?

In Dana’s case, collecting does not necessarily have to do with value. “That was one of [my family’s] complaints: ‘we throw it out the back door and you bring it in the front door.’” She admits that collecting is more of a time-traveling tool for her.

“I went through this weird thing when I was a kid of falling in love with decades one after another. It started with women’s fashion in the 1830s, and then I fell in love with the fashions of each decade in turn as if the decades were turning. I was crazy about one for every month. I was aided by the Chicago Public Library books on fashion and history. By the time I was sixteen, they showed some movies on local television in Chicago that had been made in the early thirties. It was the Marlena Dietrich and Josef von Sternberg collaborations that were so visually wonderful and so seductive and I was just hooked.”

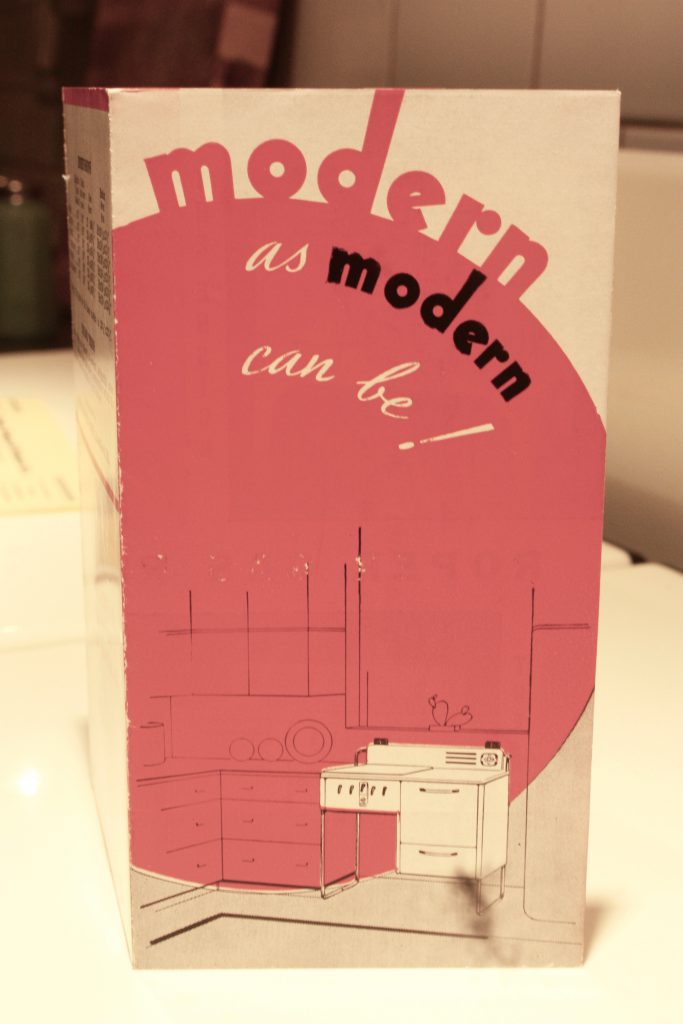

Since then, Dana’s love of the thirties has taken on many forms, one of these being her 1937 Roper stove, which she calls “Eleanor.” “She still works–works very well as a matter of fact. She’s got issues, the poor thing, but what 80-year-old doesn’t have issues? Kitchen design in the 30’s was moving towards smooth, open workspaces and part of the reason that Eleanor is designed the way she is is to give the housewife more workspace. In homes built before 1935, there were no cabinets built into the kitchen. If there was a cabinet, it was stuck on the wall and you worked on your table. That extra workspace on Eleanor was like a boom! The two lids that lift keeps the wall behind her clean, which was another real issue because not everyone could afford fancy tile and its built-in storage.”

The stove’s design has that timelessness that we associate with things that look “modern.” “Style was moving more towards what Diana Vreeland and Carmel Snow were doing,” Mees-Athruing explains. “I’m not saying they were initiating this. They were following a trend that was coming out of Bauhaus and other things. They were getting away from the Japanese influence of simple, austere line, and into more solid blocks. The influence of streamlining design was inspired by the idea of movement and speed as opposed to stasis or just sitting there and looking pretty.”

The “Working Girl” mentality of the 1930s is something that we find re-surfacing again and again in our culture. There is no better guide to this mentality than Marjorie Hillis’ book “Live Alone and Like It.” Hillis, a former editor of Vogue circa 1936, is addressing her book to this new class of women and their anxieties of being in that class. She uses case studies as her structure. “She’s writing about this person that she must have encountered while she was working at Vogue and this must be another person,” Dana points as she flips to different chapters. “She does a profile of Elsie de Wolfe, a famous interior decorator, which is shorthand because she was a lot of things. She profiles everyone anonymously,” adds Mees-Athuring.

The book’s subtitle, “A Guide For The Extra Woman,” affirms our contemporary notions of singleness as well. “Single women were always outside. As one of my teachers called it when I was at Mundelein High School, she said, ‘I’m not a feminist, I’m a womanist,’” Mees-Athuring tells me. The term “womanist,” originally an idea spread by Alice Walker, has its pitfalls in our contemporary setting. However, the phrase “extra woman” points to the propensity of a woman to be regarded as excessive and unnecessary, which is an ancient idea.

Hillis affirms the mere necessity of extra-ness, which is what makes it so appealing and relatable. Being defiant isn’t suggested— it’s necessary. Having hobbies isn’t just nice— it’s necessary. Knowing a little bit about it all— necessary. When looking at the word “extra” on Urban Dictionary, the earliest entry is from 2003. Then there are some from 2006 and 2008, and several from 2017 as the word has gained popularity through the internet. The word continues to often be used as a pejorative and shaming tool for women. It is even the example sentence for the 2006 entry: “That girl is extra.”

“Live Alone and Like It” framed my view of collecting as a form of extra-ness. A forming of extremities or extreme amenities. “I think it’s pretty much having a great, big, noisy boarding house and I’m the lady running the boarding house and taking care of everybody, and the chi that they have is a collection of all the spirits from all the people who ever owned and loved them,” affirms Mees-Athuring. Hillis and Mees-Athuring, in their writing and collecting, respectively, are merely proving that extra-ness is just an attempt to touch the spirit in everything.

It was impossible to be surrounded by these items in Dana’s house and not come to some sort of understanding of this sense of spirit. I mentioned how collecting can become a bandage for loss. There can be something in your life that you are lacking or that has affected you, and collecting is a way to reverse engineer that. Dana asks, “Is nostalgia really nothing more than grieving? Grieving with a pocketbook. How much is a collection of souvenirs and when does it just become only souvenirs?”

The idea of souvenir-ship is something that is potentially replacing contemporary acts of collecting. As archives continue to be re-assembled in response to content and context, the lens of “experience” shifts. Is one’s cataloging of a film a souvenir of the experience of this film or is the mechanism in which one is cataloging the film a souvenir of its existence? With digital and physical items blending closer together in our collections, the sense of a human trace begins to waiver of its importance.

Mees-Athuring states, “I’ve begun to see that objects do have a life of their own and sometimes they do have a spirit. A certain amount of it is respect for the object. This is what happens when you start to have a relationship to it. Truly, until we have proven that there is something beyond this veil of tears, there is no spirit in most inanimate objects and, of course, I argue the opposite– that the spirit is what draws me to these objects. These objects are time travelers, and I’m just helping them along and protecting them from the storm with the few decades that I will have left.”

There is a sentimental appeal in creating locally and nationally focused collections like those of Mees-Athuring, but the question that persists for collectors is, “what will continue to outlive us?” When our hands are no longer a part of the DNA of an object, do we begin to vanish with them, like un-thanked ushers? Who is really saving the collector’s hands?

Featured Image: The title page from Mees-Athuring’s copy of “Live Alone and Like It” by Marjorie Hillis. Photo by Zara Yost.

Natasha Mijares is an artist, writer, curator, and teacher. She received her MFA in Writing from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She has been published in Container, Calamity, Vinyl Poetry, Bear Review, and has work forthcoming from Hypertext Magazine.

Natasha Mijares is an artist, writer, curator, and teacher. She received her MFA in Writing from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She has been published in Container, Calamity, Vinyl Poetry, Bear Review, and has work forthcoming from Hypertext Magazine.