The Chicago Archives + Artists Project (CA+AP) is an initiative that pairs Chicago artists with archives and special collections to spark new experiments in creative interpretation, to showcase the rich histories and materials being preserved in participating archives, and to share archival practices with local artists and their communities. The project explores archives across the city via online features, a series of public programs and new commissioned artwork by Chicago artists. However, due to the ongoing pandemic, this current iteration of the project looks a little different. We have reimagined the project to take the shape of a book to be launched in Spring 2023: The Chicago Archives + Artist Project: Case Studies in Collaboration, which you can pre-order now! In the book, along with the wider history of the project, you’ll find the newly commissioned work of this year’s archive and artist pairing: Shorefront Legacy Center + Ben Blount, and the DePaul Art Museum + Natasha Mijares.

This series of articles profiles these featured archives and artists over the course of their collaboration, exploring the vital role of the archive in preserving and interpreting the stories of our city as well as the ways in which they can be a resource for creatives in the community.

For this installment, Lauren Iacoponi sat down with artist, writer, curator, and educator Natasha Mijares. Mijares has been published in Container, Vinyl Poetry, The Gravity of the Thing, and Hypertext Magazine. The conversation touches on the connection between artists and archivists and Mijares’ time exploring the collection of Latinx art at DePaul Art Museum, which is a collecting focus at the museum connected to their Latinx Initiative. The following interview took place between Natasha Mijares and Lauren Iacoponi on August 11 and has been edited for length and clarity.

Lauren Iacoponi: I spent some time on your website before meeting you to discuss your work with the DePaul Art Museum’s collection of Latinx art. Your work, titled “How to Find the Celia Cruz in Everything,” relates to archives in that it utilizes the white pages to reach people with the same name to inquire whether they were named after the historic singer. This work also involved a lot of humor which I enjoyed. It was such a great project1.

I particularly enjoyed your notes after reaching the second Celia, where you wrote “The second identifying Celia, age unidentified, but I guess 65, from Maryland said, “How did you get this number?” And then I panicked because I had forgotten script number one, so I hung up.”

Do many of your projects involve humor? And are there other works you have done that relate to found information or archived information?

Natasha Mijares: Humor to me is very therapeutic. I often will go to it just to, like, relax or unwind, and so I always try to think about how I can lean into it more in my work. Just because I tend to write about things that have to do more so with language, identity, place, and the environment and sometimes none of those things can feel funny (laughs), but I still feel like some of my favorite artists and favorite writers have a sense of humor, or they have a sense of levity. Just having that balance feels like a really healthy way to make art, and so I try to invite it in.

In terms of working with archives and histories, I would say, because I have worked in archives, [they’ve] kind of crept into my work. I went to the University of Miami for undergrad and worked in the special collections there, so there were just awesome collections that I had my hands on. I got to catalog a collection of smut from the Miami Beach 80s queer scene; that was super fun and filled with humor. They also commissioned some projects for me there. I feel like they were really welcoming of artists using the collection and bringing in their practice and their experience to interact with the work. I really love that this project with the DePaul Art Museum is kind of a continuation of my history doing that—and sort of the camaraderie and the openness that collection managers and those people working there really have. It’s just a great space to be in.

LI: Yeah, absolutely. How do you typically work within an archive? Since you do have a history of working within museum and university collections, how has your experience with the collection of Latinx art at DePaul differed from working with other archives?

NM: I feel like I’ve done a lot of work exploring what an archive is to begin with, and how we keep them and what they mean to us. There’s this book called The Library at Night (that I love) that really explores that. If you’re interested in books, libraries, and collections, it’s a great book.

[The collection of Latinx art at DePaul Art Museum] in particular is very contemporary, which was interesting. A lot of collections I’ve worked with have some years on them, and that contributes to the nostalgia that comes out of the writing or the work, whereas this one felt more so like a conversation rather than harkening back to an era or dialogue that’s beyond me. I’ve met some of these people, and some of these artists I feel like I can reach out to and really have a conversation. That was interesting and I’m really excited that [me and] the other artist who is working on this project at the same time as me were able to communicate about that too. His collection is more so in the past, so it will be a really interesting and dynamic with his piece and my piece in the book itself. It will have a different sense of relationship there.

LI: Yeah, that will be really interesting to see! I’m curious, do you keep a personal archive? And do you feel that this project has had an impact on the way you think about preserving your own work?

NM: I have many types of archives. I think it just really depends on what it is. My relationship with paper—I love the history of paper, what paper has been, and what it can become—I keep a lot of scraps of paper. I don’t really intend to do much with it. I think it’s more so a material connection. I want to be connected to this because it reminds me of a person or it reminds me of a place or something that I did. Whereas my relationship to using archives in my work is very project-based. I’ll probably have a different relationship with something I want to use in a project. I feel like the archiving of words, archiving of materials, archiving of voicemails—everything is kind of open to [being a resource for future projects]. It’s just a matter of if I’m going to explore something, I’m very research-heavy. I’ll spend a lot of time researching, which is a sort of archive-building, but I’m not necessarily using things that I keep in my attic or whatever (laughs).

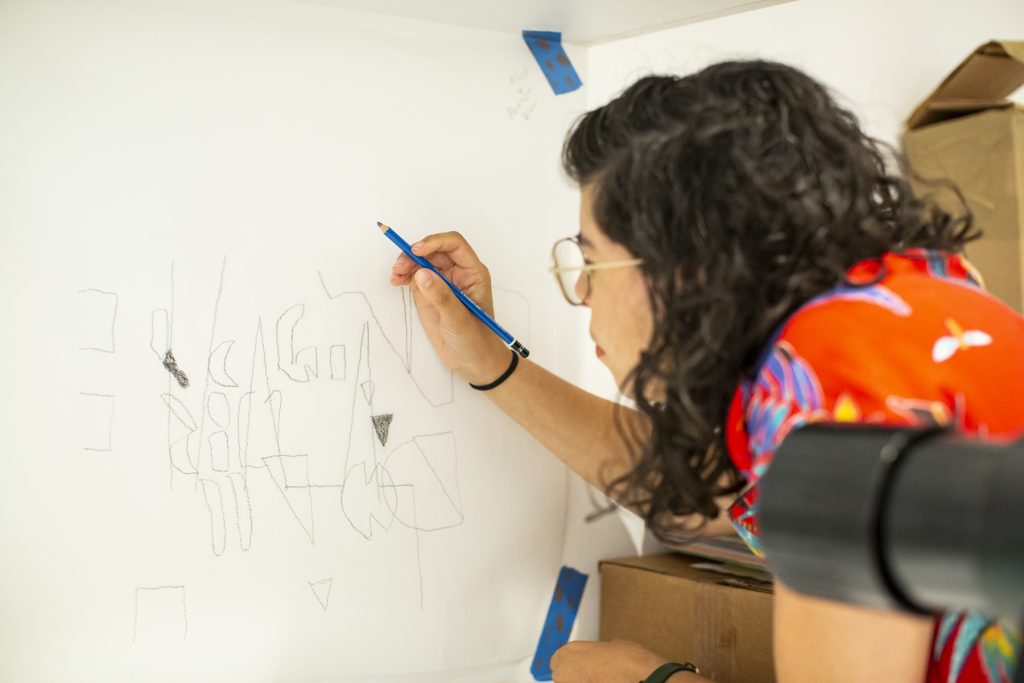

LI: Definitely! I know early in our correspondence you mentioned you’d be using Spudnik Press’s facilities to do some relief prints from tracings you did of some of the works in the collection. This will be integrated into the written component of what you’ll be contributing to the archives and artists book. How is this process going? What is your intention and some context to this work?

NM: As I was going through the archive digitally, before I even got into the room, I looked at the collection’s website and picked out some of the artists that I really wanted to dive in with. I really wanted to explore a visual representation of these artists coming together. In exhibition-making, there’s a very specific form of creating a visual culture. Since I primarily work with writing and image and mixing those two together, I wanted to create a language or set of criteria to move forward with. I really love opaque projectors and using things that are not the most digital or high-tech way of doing things; I love the faultiness that can come from archaic materials and old technologies. It can lead to happy accidents and a window of looking into things that create more ambiguity. So I used a tracer within the space.

I would kind of do this little dance between having the collection out, taking some notes, doing some writing and some free responses, not really thinking too hard about it, then I would turn the lights off and do some tracings. It felt like day and night, passing through time and working with the material in multiple ways to have different results. With the tracings themselves, I would put the tracer on top of the image, working mostly from works on paper, and I would only crop a piece of the image. I would take visual elements from a small part of the image and I would do that for multiple pieces, so each tracing is kind of like an amalgamation of two to three artists, collaging their visual styles together to create a new image.

LI: Oh, wow. I was not sure what that project entailed and I haven’t had a chance to look at it yet so I was really curious about that. What have you found yourself exploring within this archive? What has the trajectory of your research been like?

NM: I love that a lot of the images and works that I looked at have this sense of place referring to or connecting to migration or temporality; or how we connect to where we are from and where we are going. That was really present in a lot of the work, which is very emblematic of Latinx culture and having a motherland, or maybe not having a deep relationship to it—that all kind of rang true in all of the work. As I was in the space incubating ideas, I let myself free-write, because when you are getting source material, at least with my process, I try to turn off my editor brain as much as possible, and let the process be fun and generative and not think too hard about it. Then going through my notes and seeing what are the through lines here, what could this become, and what is this saying. As I was processing my notes, I realized a lot of what I’m looking at is analyzing and processing death, dealing with how that shows up culturally, how that shows up personally, and that it’s both communal and individual. It’s such a global thing in art: so much of art is about death. It was interesting to see the different shades. From there, I’ve been working on absurd processes within death. It’s kind of like a guide or maybe harkening to Dante’s Inferno. Thinking of different forms of death and what that means. A lot of my work is myth-making or mythologizing something that either already exists, or kind of collaging these ideas (because we’re always doing that in art) to put our spin on it. It’s a fun way to process something that is just inevitable.

LI: Are there any works in particular that you wanted to speak on that relate to death?

NM: Yeah, I would say the Maria Gaspar2 piece, the Mario Algaze3 pieces, and the Harold Mendez4, all three of them. Those really sparked that idea. They either had to do with the spaces of a church or emptiness within the subject or space. Maria Gaspar’s is more of an environmental take on how death happens in spaces—in that particular piece it’s a rural space that you don’t think about.

LI: It no longer reflects that history.

NM: Right! There’s nothing to commemorate the history that’s happened there. Then with Harold Mendez, it’s very ceremonial and interactive, and sculptural. They all kind of had different takes on how they process a sense of cultural or historical connection to death and something passing.

LI: Are you working with the Mendez piece in either your writing or tracing?

NM: I am, in the writing. It’s not something that’s able to be traced really (laughs). But I love that one, I think it’s really fascinating.

LI: Yeah! I talked to David [Maruzzella] from the collections at the DePaul Art Museum about that piece, the intention of the artist, the material specifications, and the difficulty of installing the work. It’s interesting to think that, in a sense, it doesn’t exist outside the context of being on exhibit because of its reliance on the heavy marble which is destroyed after each exhibition since it’s far too heavy to store! I like that. (Both laugh).

You also spent some time with Angel Otero’s work, Volar (2011). I researched similar works of his in 2015. Otero’s “Oil Skin” paintings transition from representational works to unrecognizable abstractions. Initially, his works reference Baroque painting on plexiglass, then move towards a process of anti-painting through destruction, collage, and assemblage. How does your work with this archive reference his unique process?

NM: This is my favorite kind of work. It is very similar to my own process with this piece. It has both historical elements and a very physical element. The actual piece itself is beautiful! It’s a separate experience entirely, it creates associations that have nothing to do with the origins. It creates its own kind of life. Even the word “volar” has a lot of multiplicities. It has a visceral quality that I enjoy when experiencing any type of art. I love when painters use the term “juicy,” meaning a thick application that is almost sculptural, like you can feel it, it’s almost like a body. I really enjoy that kind of work and the grandiosity of it. I feel like that one and the Harold Mendez piece felt the most difficult, and they take up a lot of space. David and I were talking about these sorts of difficulties, but that kind of art needs to be seen. If you’re going to be an artist, you might as well go for it!

LI: Yeah. Do you have a favorite piece of art you’ve come across while exploring the archives? What interests you about that piece?

NM: Hmm…I like a lot of them. If I were to pick—maybe because I already have a relationship with this work—all of the Dianna Frid pieces. I’ve interviewed her before and I’ve met her. She’s so sweet and I really respect her process and the kind of trajectory she’s on. It was very nice to be able to interact and collaborate with that piece on my own terms having known the artist and done my own research and exploration from a more journalistic perspective.

LI: I’m excited to see what you do with that! You also mentioned that you looked at Mario Algaze’s photography. Were those some of the pieces you were referencing in terms of open spaces?

NM: Yes, those were.

LI: What materials and tools have you been important in the making of this work? I know your work is in process, so what are your next steps?

NM: A lot of the materials I’ve been utilizing have been books. That’s just part of my writing process. Tapping into a lot of books that have to do with themes of the works or themes that are present in my writing. Some of the books I collected were Home in Florida by Anjanette Delgado, which is an anthology of Latinx writers specifically writing about Florida. [Sexual Futures, Queer Gestures, and Other] Latina Longings [by Juana María Rodríguez] is more of a scholarly text that talks more about queerness and language. There are many more, but those are the two that come to mind first. Working with both my own text and other texts to understand where connections already exist and see how I’m speaking to them. In terms of more physical materials, I have my traces and I’m doing linocuts. I really like that process because there is a connection between Latinx culture and specifically relief and woodcut, so I really like that. There’s already a natural connection there and I like the process in general. It’s a very collaborative and freeing process. The print process for me really opens up to chance circumstances and things changing, and I feel like that is really good for my writing. It helps create a relationship, forms, and ways of physically formatting and interacting with writing that feels very charging.

LI: How often did you visit the DPAM Collection for this project?

NM: I went four times.

LI: Do you know how long you spent each time you went there?

NM: I think I spent three hours each time I went.

LI: Yeah, when I went to speak with David I was there for about three hours. You can really get lost in there.

NM: Yeah, I tried to make sure I didn’t spend too long in there because it can really tire you out mentally. It’s overstimulating. (laughs).

LI: You mentioned you looked online before going in person. Did you mostly stay with the artworks you intended to explore, or did you find yourself attracted to something different?

NM: I kind of gave a list to David to make his life easy. But as I was picking things, he was also noticing what I was gravitating towards and he started to pull things for me. It’s like a curator. Since he knows the collection so well, he could pick out pieces from different areas of the collection. We had to walk to a library and he was pulling stuff there. Even when the photographer came, he pulled stuff for her. It’s like this artistic matchmaking, which was really fun.

LI: Do you feel like you collaborated with him in a sense? Did you have many discussions about the work?

NM: Yeah, we had a couple of discussions, mostly about processes and why things are kept in a certain way. I love the nerdy, conservation aspects of it. I find that very interesting, and the fact that these pieces live in a university museum and how university museums are different than other cultural spaces, we talked a lot about that. I feel like our conversations were very natural and just happened when they happened.

LI: Yeah. Talking with David, I learned university collections are much more accessible than I realized.

NM: I think all collections are more accessible than the public realizes.

LI: True. I wanted to circle back a little and ask how Maria Gaspar’s site-specific performance work resonates with your practice.

NM: I see a lot of connector points with her work in general. I really admire her attention to space and history, and how she weaves those things together. I love when you can see a lineage within an artist’s work. I would be honored if someone said they could see the connections there. That kind of work feels very natural. I’m always exploring our relationship with nature and more specifically language and nature. We create things that come from our surroundings, and in our modern conditions that’s become so queer. I’m always fascinated by that: artists who represent that visually or in a performative kind of way—those are always giving me that kind of juice.

LI: I know you mentioned over email some other artists outside of the Latinx collection you were looking at, like Betsy Odom. Did you end up using any of those works in your research or conversation or did it not really come up?

NM: I looked at those because it was a handkerchief series and I’ve also done a handkerchief series. It was more so like, ‘oh this is something that’s showing up in my work as well!’ But yeah, I would say that it’s in the mix. A lot of things are going to show up in the writing, but it may also leave the writing at some point during the process. But I really enjoyed the material quality of that work. For me, writing isn’t always about what it is, but it’s about the feeling of touching it or seeing these things next to each other. One thing I really liked about this project is how I could have multiple pieces next to each other and not in the same way you typically see the work on a gallery wall, and bring things together and write across the lines of these works. It created an intimacy that you don’t always get with this kind of art. I really liked that.

LI: That’s true. Seeing the work with David was way more intimate than if I were to see the work in the context of a museum.

1 Natasha Mijares. How to Find the Celia Cruz in Everything (2019)

2 Maria Gaspar, Disappearance Suit (Marin Headlands, CA) (2020)

3 Mario Algaze, Club la Paz, Bolivia (1981); Doce Angulos, Cuzco, Peru (2002), Two Girls Kneeling, Barva, Costa Rica (1987)

4 Harold Mendez Let us gather in a flourishing way (2017)

Chicago Archives + Artists Project: Case Studies in Collaboration serves as a site for new archive-inspired explorations, a directory of Chicago-based archives and collections, and a printed space where past artists, archivists, librarians, curators, and other collaborators can reflect on 5+ years of the Chicago Archives + Artists Project.

The book features two new artist/archive pairings with printmaker Ben Blount who spent time in the archives of Shorefront Legacy Center, and artist/poet Natasha Mijares who explored the Latinx art collection at DePaul Art Museum. Edited by Kate Hadley Toftness, with support from Tempestt Hazel, Christina Nafziger, and Persephone Van Ort. Designed by Matthew Austin of For the Birds Trapped in Airports.

The book also features writings from Oscar Arriola (Zine Mercado/Chicago Public Library), Sara Chapman + Dan Erdman (Media Burn), Sky Cubacub (Rebirth Garments), Meg Duguid + Michael Thomas (Culture/Math), Marc Fischer (Public Collectors/Temporary Services), Kate Hadley Toftness (Sixty), Tempestt Hazel (Sixty), Ivan LOZANO (CA+AP Artist), David Maruzzella (DPAM), H. Melt (CA+AP Artist), On the Real Film (CA+AP Artists), Jennifer Patiño (Sixty), Jessica Pushor (Chicago History Museum), Morris “Dino” Robinson (Shorefront), Robert Sloane (Chicago Public Library), Nell Taylor (Read/Write Library), Lauren Shadford (Voices of Contemporary Art), Darryl DeAngelo Terrell (CA+AP Artist), and more.

About the Author: Lauren Iacoponi is an artist, curator, writer, and arts administrator living and working in Chicago, IL. Iacoponi received her MFA from Northern Illinois University with a Certificate in Art History and her BFA from Columbia College Chicago with a Minor in Art History. Iacoponi is the Director and Founder of Purple Window Gallery, an artist-led project space in Avondale and the Director and Co-founder of Unpacked Mobile Gallery. IG:@lauren.ike

About the Photographer: Kristie Kahns is a photographer and art educator based in Chicago. Remaining close to her first passion of dance, she has spent over a decade as part of the Chicago dance community through her camera. She is also a dedicated teaching artist, creating analog photography programs for teens. She is currently a graduate student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, studying art education and administration.