The Chicago Archives + Artists Project (CA+AP) is an initiative that pairs Chicago artists with archives and special collections to spark new experiments in creative interpretation, to showcase the rich histories and materials being preserved in participating archives, and to share archival practices with local artists and their communities. The project explores archives across the city via online features, a series of public programs and new commissioned artwork by Chicago artists. However, due to the ongoing pandemic, this current iteration of the project looks a little different. We have reimagined the project to take the shape of a book to be launched in Spring 2023: The Chicago Archives + Artist Project: Case Studies in Collaboration, which you can pre-order now! In the book, along with the wider history of the project, you’ll find the newly commissioned work of this year’s archive and artist pairing: Shorefront Legacy Center + Ben Blount, and the DePaul Art Museum + Natasha Mijares.

This series of articles profiles these featured archives and artists over the course of their collaboration, exploring the vital role of the archive in preserving and interpreting the stories of our city as well as the ways in which they can be a resource for creatives in the community.

For this installment, Lauren Iacoponi sat down with the Collection & Exhibition Manager of the DePaul Art Museum David Maruzzella to discuss the collection of Latinx art at DPAM. The following conversation took place between David Maruzzella and Lauren Iacoponi on July 26, 2022 and has been edited for clarity.

Lauren Iacoponi: What got you started in museum archives, and in what capacity do you work with them now?

David Maruzzella: My experience with archives comes from academic research that I was doing a few years ago. I had spent a fair amount of time at an archive center in France outside of Paris. It’s an archive center for modern and contemporary French philosophers, writers, and artists. It housed archives from really big-name philosophers like Michel Foucault to french filmmakers and writers. I had been doing some academic research in the archives. I would go every summer for a week and you can check out piles of documents, typewritten book manuscripts with corrections, and that sort of thing. The research was also mechanical in a way because you’re only there a certain amount of time and you’re looking at this material that not that many people have seen. I was mostly at my computer transcribing everything that I was reading or trying to speed-read things and write summaries of what I was reading. That was mainly my experience with archives prior to working at DePaul.

Part of my everyday work here requires doing something with the collection. We have a lot of classes at DePaul that visit [the DePaul Art Musem’s Collection Study Room]. We do custom pulls for classes, so either a class will ask to see certain things, because we have a public-facing collection database that they can look at, or they’ll ask for recommendations from myself and my colleagues. It could be a class about anything; we’ve had a class concerning the environment and a class about modern contemporary art in Chicago, so we can do custom recommendations and fill the room with things that we have in the collection on a case-by-case basis.

LI: Sort of a miniature survey?

DM: Yeah. Exactly, exactly. Again, sometimes they have requests but part of it too is that we can pull things that they might not have known about, or sometimes we have new things that haven’t been processed yet, so they’re not on the database yet. I’ve described it in the past like running a record store or a used bookstore. People come in and they know what they like, and they ask, do you have any of that? And I can pull out examples of what they are interested in. Part of the beauty of this space being pretty small is things are at your fingertips.

Working with Natasha [Mijares] was the first time I’ve directly worked with an artist in this space. She was unbelievably easy to work with and super cool to meet. She explained to me that she finds other artworks quickly and powerfully inspiring and [they] make an impression on her. So the moment I took artwork out and put it in front of her, it kept her interest and I left her to her own devices. Each day I would set out a different group of things she requested or I would pull out other things she either didn’t know about or maybe missed while looking through the database. We acquired a piece days before she got here that wasn’t in the database yet from the LatinXAmerican show, a piece by Tanya Aguiñiga. It’s a video work but also includes this cloth. We acquired the video and the cloth. We looked at a lot of pieces, pulling out multiple things from the cabinet, and I said to pick out anything that catches your eye. So we did that, like I mentioned it was a lot like a record store. We also went over to another storage space, the library. It was awesome. I’m really curious to see [her] new works based on what she saw here. I think that will be cool.

DM: We’ve had other small collaborations with artists, but this is the most extensive and ongoing one that I’m aware of at least since I’ve been here, which has been a little over three and a half years.

LI: If other artists wanted to work in the archives in a similar way, is there a process set up for that? Or maybe not since you said it wasn’t exactly common. But if people are interested, is it possible for other artists to do similar research?

DM: Yeah, I think it would be amazing to have more people in the space. I don’t see DePaul University necessarily branding itself as a research institution. Professors and students at DePaul aren’t often actively looking to explore the collection, besides the occasional class visits, but I’d love to have more artists and students coming in and using the space. That’s what I see it as being here for. Being part of the university, and having an academic background myself, I see it as a resource for scholarship and study and also just having a different kind of experience with art than you would have at an exhibition. This is something Natasha and I talked about, the difference between seeing art, in the context of an exhibition, and the goals and outcomes of an exhibition experience versus the goals and outcomes of a collection visit, which is more meandering and unstructured in a good way. The exhibition tends to create a certain effect, it’s created and curated and organized, and displayed in a way so as to communicate something specific, whereas the collection is more aleatory, you can move from one thing to another thing and [see] something that you didn’t even know was here, in a much more experimental way.

LI: You make your own associations that are not curated.

DM: Yeah, exactly, it’s less curated. It’s obviously curated and structured in some way. Because we both inherit the collection that’s bestowed to us, that is to say, we inherit the collection as it was imagined by someone who I’ve never met before, working here fifty years ago, who wanted to collect whatever it was that they were collecting. Then compared to the way the collection vision works now, it’s a combination—you inherit a collection of objects and then combine that with the current vision. That’s a form of curation, but maybe less curated than an exhibition which is a more controlled experience.

LI: Exactly. Are there people who ask to curate exhibitions on loan from DePaul’s collections? How does that work? I know, for example, the exhibition LatinXAmerican was on loan at the Lubeznik Center for the Arts from the DePaul Art Museum.

DM: I would say every year there’s a fair number of loans that go out of the building. More and more these works are being called upon to be loaned out. That exhibition at Lubeznik was the first time we ever took an in-house show to another venue. That was a show we developed within this museum by curators here over a long period of time that was interrupted and reworked due to COVID. It was put on pause but was reshaped into a different context with different people being involved, and with almost fifty percent completely different works than it had originally been conceived in 2018 or 2019. That was the first show we had ever done in-house that then traveled. Which was A) a learning experience and B) exciting to see so many of the newer acquisitions and collection vision get appreciated in that way.

Other than that, we lend out a fair number of works, all kinds of things. Just recently we had some Andy Warhol Polaroids go to Aspen, Colorado for a big Warhol exhibition that they had. We had this really amazing painting by Gertrude Abercrombie that will be going to the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh. We just sent a Ralph Arnold piece to the Museum of Contemporary Photography at Columbia. There’s a fair amount of incoming, and outgoing collection traveling, I expect there will be more on the horizon.

LI: I have a friend who works at the Lubeznik Center of Art, and she mentioned from her understanding there was originally a gap in the collection here at DePaul for Latinx artists. Can you speak about the museum’s recent acquisitions? I noticed there are a lot of Chicago artists. How did the collection evolve?

DM: Yeah, that’s a great question and it’s also reflective of how the show evolved from how it was originally formulated to what it ended up being. In the years prior to that particular exhibition, there had been shows that were aimed to alter the landscape of representation for Latinx artists, particularly in Chicago. Everything we do here always tries to have some amount of Chicago focus. It’s not only Chicago, but that’s always part of the story we are trying to tell with our exhibitions. It’s almost a challenge to other institutions in the city, you don’t need London or Paris or LA or New York, we’ve already got it here if you just look in your backyard and see what’s already here. I think the Latinx side of things also arose from that.

It’s about trying to accurately reflect the community and reflect the student body at DePaul and then reflect the changes and things happening across the country. I always thought of LatinXAmerican as a show that was trying to redefine what American Art was. That tended to be the perspective that I saw. To me that was the most radical way to look at it, to make the argument that this is American Art now. This is an integral part of what it is. We had been doing shows in that vein, or with light connections to thinking about Latinx representation in Chicago and across the US over the years prior to that.

When the exhibition LatinXAmerican first started the goal was to have it be a collection show. It was to highlight new acquisitions that came in over the past four or five years, from 2016 to maybe 2020, then also finding other things in the collection that had never been shown before. But my memory is that when we were working on the show there were times when we were really reaching to fill both floors of the museum with only works from our collection. It meant having to keep expanding what it was we were trying to show because we did not have enough work to do two floors full museum exhibition of contemporary Latinx artwork. We were stretching into other domains in order to keep it all in-house. We have a Diego Rivera painting, which technically, in terms of classification and definitions, isn’t really a Latinx artwork, it’s a Mexican artwork. Diego Rivera is a Mexican artist. If you want to keep using the language of Latin American, it’s a Latin American work but it didn’t fall into how we were defining Latinx, which was Latin American descent in the US. There were moments like that where we were trying to make our works do things that they couldn’t do.

The exhibition then became much more of a focus on contemporary Latinx artists. All of that older, historical part was taken out. I think it also became more self-critical in an interesting way, we showed maybe 60-65% from the collection then maybe another 35-25% or so were loaned to the museum. That was meant to show that we weren’t able to do the show that we wanted to do, we didn’t have a museum’s worth of contemporary Latinx works in the collection. We had 60% but we didn’t have 100%. The loans were meant to highlight the gaps in the work we were doing and be transparent and self-critical about where we were at. The upside though was that that show allowed us to acquire a lot of those works that came to us first as loans but then became acquisitions. A lot of the credit lines changed from being courtesy of the gallery, artist, whatever, then to being part of our collection by the time it was on exhibit at the Lubeznik Center.

LI: That’s really important.

DM: The aim is not just about having contemporary exhibitions, it’s about adding to the collection and being involved in the financial life of an artist, acquiring their works, adding them to our collection, and being able to have longer-term relationships with them now that they’re part of the collection, programming, traveling the show…I mean everything. The only thing we didn’t do yet, but I think it may be something on the horizon, is a publication. We didn’t do a publication for the exhibition, but I can imagine maybe [there will be] a collection publication in the future. I think that will be the final step in the typical ways we work: exhibitions, acquisitions, programs, and publications.

LI: How does DePaul Art Museum’s collection of Latinx art grant access to and engage with the communities it represents? Do you feel that is important?

DM: Yeah, absolutely. I think that the role we try to play with the museum is to be a reflection of what’s going on around us and also do that critically. That can look a lot of different ways, but one part has to do with accuracy. To accurately reflect what’s happening in the community and in the city as it evolves and changes. I think as a university, the forces at work here are maybe different than at a gallery or the Art Institute or the [Museum of Contemporary Art] where the mission and the goals and also the funding and sort of logistics of the whole place may be different. That is not to say that universities are free from money and politics and influence and power, because they’re a thousand percent not, but the way those things manifest themselves is different. What’s interesting about what we can do with the collection, with the archives here, is that we can be guided by principles that are different than what another institution will be guided by. Again, like anywhere, we have to think about financing and budget, but we don’t necessarily have to follow trends like a museum or gallery that lives off of admission. We can hopefully take risks or pursue different lines of research that may not be productive in those same ways, which I think is maybe the most important thing a university museum and collection can do. We can pursue something even if it’s not currently trending in popular culture or popular consciousness and if it’s also not trending financially, we can still pursue something. That’s what I think research is, researching something for its own sake and not for the sake of these other forces. I think that allows us to shift the balance of power, hopefully in positive ways. We can start to change the way institutions work or the way representation works in a way that’s not fully co-opted by those other forces, and we can put those things on the map and on the agenda in a way that maybe other places can’t.

LI: Absolutely. It really is a reflection of the community. I’m familiar with many of the artists in the collection, as someone who visits Chicago galleries and DIY spaces. Artists like Edra Soto are in the collection — it is a reflection of the community and the project space in her own backyard, The Franklin. As a Chicagoan who attends the exhibition, I can recognize that.

DM: Yeah, Edra is such an important Chicago figure, she’s so part of the infrastructure, and an institution builder herself. Or whatever you want to call The Franklin, more so a sort of para-institution or something. It’s what’s interesting about what you can do under the aegis of an institution like this, you can bring something into existence. Everywhere has a DIY scene or an underground scene or something working off of the mainstream. Any town, any place in the world. What we can do here is bring attention to it in a more structured or formal way, so it doesn’t just disintegrate or disappear. Maybe in fifty years what we did here at DePaul will be helpful for remembering and having archived and documented this particular scene the way that we experience it now. Without that larger, institutional support you don’t know what will happen. There are some incredible people who just document things for their own sake. Someone like Marc Fischer. He’s such a perfect example. He documents culture just for the sake of documenting it. But making an institutional memory out of it is really interesting and bringing those figures into a collection. To have the ability to not be pressured by the same pressures as other places. We can chart our own path. To be creating our own universe, while other people are following the market or trends, we have a more sort of “authentic,” to use a loaded term, connection to certain people, groups, and artists.

LI: Yeah, like a survey of the current landscape in Chicago. We were discussing a way to document or archive this moment in time, and the idea of potentially putting together a publication in the future. That reminds me — Meg Duguid, who heads Columbia College’s galleries, put together the publication Where The Future Came From in 2020. She curated an exhibition around it at Columbia’s Glass Curtain Gallery and it was all about the DIY artist-run spaces in Chicago. The exhibition was a literal timeline on the wall of where different DIY spaces were, how long they existed, and who were the members, and it was primarily female-run spaces. I believe The Franklin was included on the timeline. That’s just another example of university institutions, I don’t want to say legitimizing, but paying respect to people who make the art scene so vital and alive in our city. It’s really important work. So it’s amazing to see these artists now acquired into your collections formally and officially.

DM: That’s a great way to put it. Because the point isn’t to say only if you are represented in an institutional archive are you legitimate, it’s actually the opposite, right? You can legitimize your own practice without the seal of approval of an institution. But what is interesting is when that process of self-legitimation becomes so strong that it then forces an “Institution” with a capital “I” to adapt and change what they do to take note of these other groups. Then the people outside the institution, the artists, communities, and spaces then shape what the institution is. I think that’s something we are interested in here at DePaul. It’s not about us from in here, in this room, saying, “this is what we decree.” Obviously, we’re curating, selecting, and making decisions, but we let the work that we do here really be guided by what’s outside of the museum walls. We’ve been trying to work with artists that are challenging the very notion of what it means to be an artist or make work, just seeing how that also impacts what we do. [By] trying to be reflective and open to being altered by what artists are doing, as opposed to feeling that institutions must set agendas for everyone else, we let ourselves be shaped by what people are actually doing.

LI: What are some of the challenges that digitalization brings to working with archives?

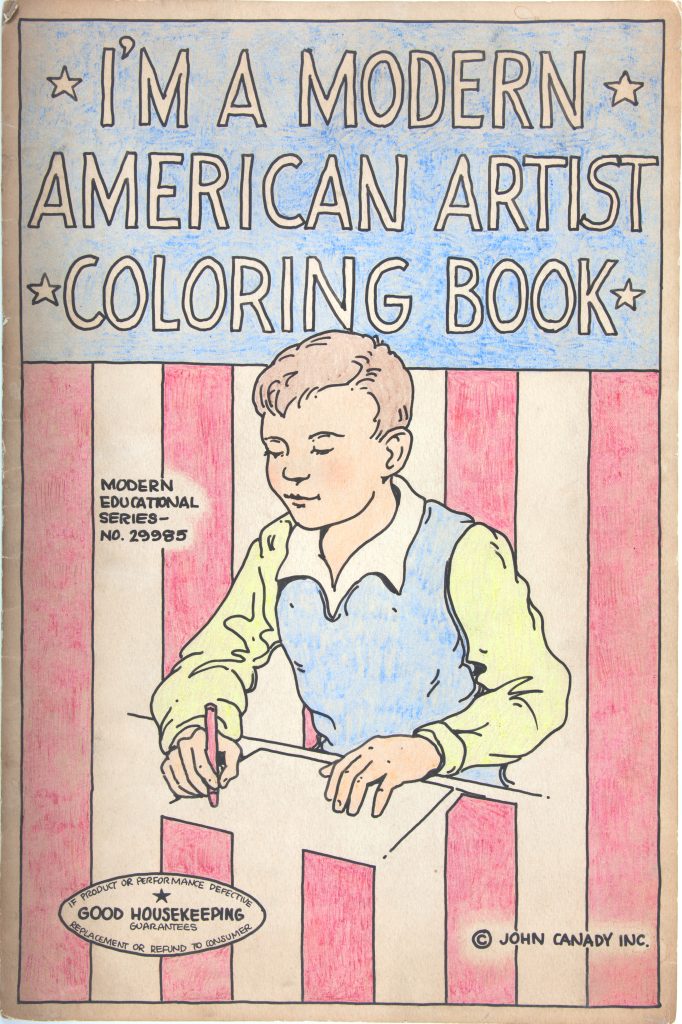

DM: It can be anything from a name mistyped in the database that can cause immense confusion, to a piece that may have uncertainties around its provenance or life outside the collection. Or things that were input incorrectly, sometimes there are two pieces and not one or it’s a two-part work. I recently was going through some of the flat files and found this amazing work that had never been cataloged. There were papers for it but it had never been input into our system so it wouldn’t come up on the database search. This happens all the time. Especially working with students in this space. Any number of things happen, like a pandemic happens and you were right in the middle of cataloging some big donation and then boom we’re not here for two years in person, and you come back and pick up where someone left off and try to make sense of their work. I found a work in one of our cabinets that had never been input into the system, it had an acquisition number and paperwork. It was this amazing coloring book by an artist I had never heard of him before but who turned out to have been a member of Fluxus. His name was Jim Riddle. We have this work that was this big portfolio called something like Modern Art Coloring Book and each page was this cartoony depiction of another work by a contemporary artist. Then a person could, in theory, color it. On top it said, “I’m a Jackson Pollock,” and then it had a drawing in black and white of a Jackson Pollock-esque image, and in principle, you could color it in. It’s this wild, goofy, playful, Fluxus thing. I couldn’t find out much about the artist. His name comes up on a couple of things. Just this weird stuff that gets here. Throw in a little human user error and glitchy technology and you have endless hours of work. (I’m A Modern Artist Coloring Book, 1962-1693, Jim Riddle)

LI: What kind of databases do you use when you are searching for an artist?

DM: For this particular artist I was doing anything. I was googling him, I was trying to see if anyone else had copies of this work. It has a large, artist-book feel to it. I was looking at other museum collections and the DePaul library database. Then the weirdest thing happened, the woman who donated it, out of the blue emailed me. At the same time that I found this piece. She made the donation maybe ten years ago before I was working here. She emailed the museum and said that she had made this donation and she had some books that we may be interested in as well. Her brother was a sculptor and she had donated works by her brother to the collection and then this random set of Fluxus pieces. In her email, she offered to send catalogs of her brother’s work. I said sure, then I told her I had found this artist’s coloring book and was curious to know more because it had never been put into our database in the ten years since she donated it. She said the artist was this guy she knew a little back in the sixties, he was a friend of her brothers and then she sent me a picture of her with this guy. She said she didn’t really know what happened to him after that, he was hanging out in New York in the sixties with all those people and she had a poster that he made in her college dorm room, and that’s about all I know. The whole thing is full of really weird stories and people.

LI: That’s very interesting. That’s such an amazing coincidence.

DM: It was almost spooky, but it was really cool. I still can’t find anything else out about this artist.

LI: That’s so wild. I also feel like things getting lost in collections is more common than people think. I know of an artist personally who has an editioned photo from the seventies that belongs in the collection of the Art Institute, the Museum of Contemporary Photography, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and a couple of other places. But the Museum of Contemporary Art has it, but it isn’t archived anywhere, it’s lost in their collection. It’s gone missing.

DM: Maybe if you told me that five or six years ago before I started doing this work I might’ve thought, how is that possible? Isn’t that a whole team of people’s job to make sure this doesn’t happen? But all I can say is it’s so easy.

LI: Right, it goes into a cabinet or something. Suddenly it disappears.

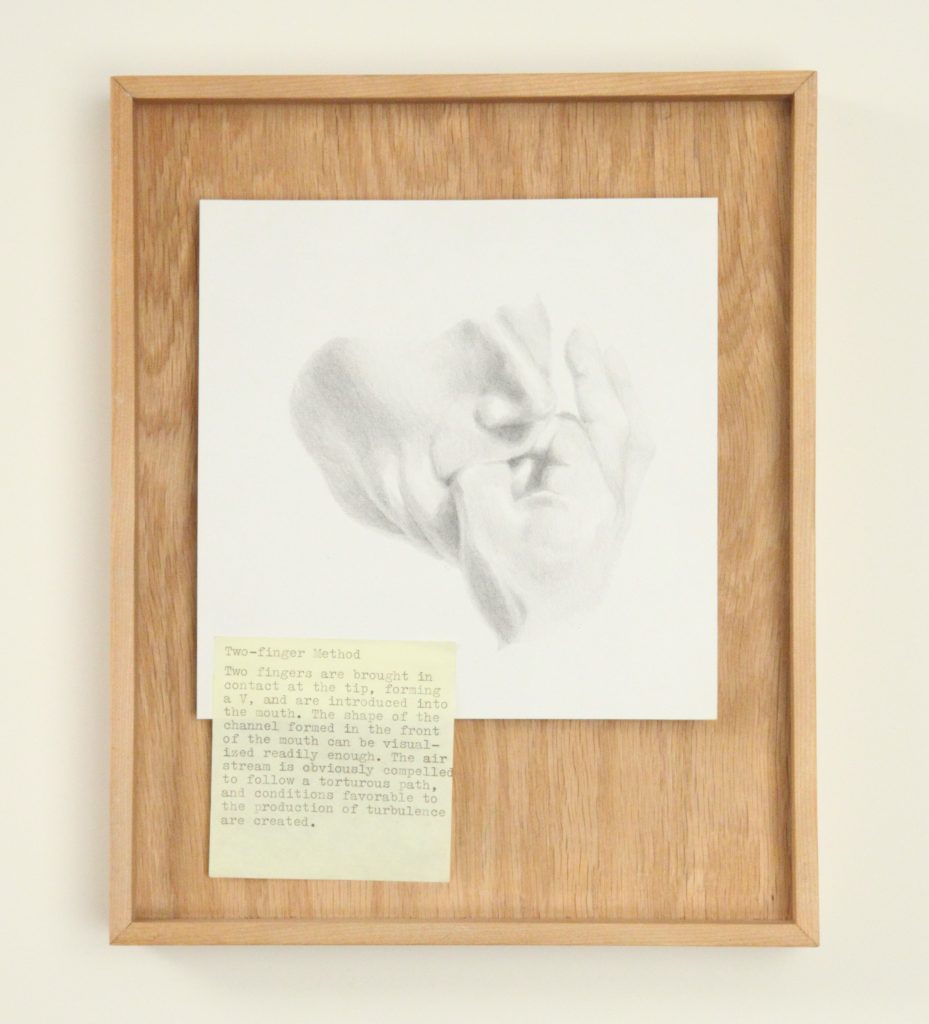

DM: The other thing that’s maybe more common, is you’re looking at the work, holding it in your hand, but you can’t find its matching digital stand-in. Maybe it got put in incorrectly. You could be searching for the correct artist but it’s misspelled. These really goofy little things but we’re humans and we still make errors. I know tons of artists over the years have done collection interventions and digs.There’s an artist we just added to the collection, Gala Porras-Kim, who’s from the LatinXAmerican exhibition. We acquired two of her works after the show. She does a lot of collection-based archival interventions. She went to the Peabody museum at Harvard and was doing a project where she was looking for all of the ethnographic objects that didn’t have acquisition paperwork and then did an exhibition based off these mystery objects. All of these places, like the Harvard Art Museum? Filled with mysteries, uncataloged things, and the unknown. Any collection big or small is ripe for artists who think in that way to come find things. (Notes after G.M. Cowan 10, 2012, Gala Porras-Kim).

LI: How do you organize the items in the archive? What specifically are you archiving with each piece? Artist statements as they relate to the work? Provenance? Exhibition history? Artist biographies? If it was donated versus acquired? Do you ever have appraisal reports or information on the acquisition price?

DM: Yeah, totally. All those things in principle are information we would want to have for every object if possible. Obviously, we have about four thousand objects, and like I was saying before, part of it is just inheriting what the person before you was doing, so it’s kind of an infinite project to get everything updated to how you would want it to be. But we always know the distinction between an acquisition and a donation. Most of the things that we have in the collection come from donations. I would say most of the older objects in the collection are donations from all kinds of people. In principle, we try to keep an archive of any books, exhibitions brochures or flyers, or postcards that people have for a particular artist. We have all kinds of old receipts and reports. Sometimes the information we get is directly from family members. But we try to keep track of all of those things. We keep track of exhibition history.

At least what we’re aware of, like if we’ve shown it, when we’ve shown it, or if something’s traveling. We have a really cool database that allows me to do a lot of different things, including uploading labels that we’ve written. So all of the Latinx work, for example, include labels that we had in the show. That’s always an ongoing project I work on with the students, providing as much information as available.

LI: It’s great that you include that information. We talked a little about Chicago artists like Marc Fischer and Meg Duguid. Aside from the active approach to archiving, what role do artists play in taking action to preserve community histories?

DM: Depending on the artist and the way they work, there are two main ways I can think of.

There is the literal way in which they produce documentation of a particular community. For example, some of the works we were able to acquire through LatinXAmerican were photographs by Diana Solís. I don’t think she had ever shown before. She had been a photo journalist for a long time and had this incredible archive of thousands of photos. It was with the help of Nicole Marroquin, who was also in the exhibition, that we came across her work. Nicole was helping Diana process her archive. So we ended up showing fourteen photos that Diana had taken from the 70s to the 90s from self portraits in her apartment in Chicago to LGBTQ protests and all types of pride events from over the years, which we showed and then added to the collection. Those are community documentation in the most literal sense.

Then sort of what we were saying before, adding artists to our collection and making a long-term commitment to them is itself a kind of community documenting. There’s both the literal documentation of the community as they were, like you might see in a photograph, and then the fact that adding artists to the collection allows a bit of the city, the community, or an individual and their network in the archive or the collection. A museum collection is a secular form of the afterlife. This is a space where we make this commitment to letting something potentially live forever, or at least a very long time, in a world of so much disposability. A good archive gives something life for centuries or even millennia. Museums and collections are like afterlife sites where something can live forever, and someone can live through their objects for a really long time, which is strange and fascinating.

LI: Yeah, archives are so important in terms of cultural preservation. What has been your favorite piece of art, object, or material that you’ve come across while working in the archives?

DM: That’s such a hard question because it changes all the time. I think I have a favorite piece in the collection… it’s really small. It’s this painting by Gertrude Abercrombie called Split Personality. The colors are perfect, it’s in really beautiful condition. It’s an amazing work.

LI: Was Gertrude Abercrombie a favorite artist of yours prior to coming and working with the collection? Was she a Surrealist?

DM: No, I don’t know if I knew her work before working here. This is the only piece we have. She was an imagist, proto-Surrealist. She had these crazy salons at her house with jazz musicians and all kinds of artists who were in her orbit. Often these sparse, spooky interiors, often this vase figure, a woman figure, or a cat figure, that appears in them. We also have this huge book on her work. One day we pulled this for a class visit, and a student asked if there was a second image with an opposite orientation and we were looking through the book and there totally was one. It was amazing, just pure student insight. (laughs)

LI: Since you were here working in the collections during the LatinXAmerican exhibition, what were people’s reactions to that exhibition?

DM: Unfortunately that was a weird time, when we first launched that show we only launched it digitally. We opened that show in January 2021 online first. We made an exhibition website which we had never done before and we are continuing to do that.

LI: Yes, I remember seeing the website.

DM: We installed the show, photographed it and made a click-through tour with the tech folks at DePaul to make this. They sort of built the basic structures for it and we gave all the content for all of the artists, the works, the labels. We do this for all of the exhibitions now.

LI: This is an incredible way for people to access all of this information.

DM: We try to make it as accessible. I also participated in Ivan LOZANO’s Archives + Futures podcast where I talked about the show. This is also the first show information we made bilingual.

LI: Amazing.

DM: I’ve now learned how to manage the website. That’s another way we archive things.

LI: It’s a beautiful platform too. What do you hope that people will be able to learn from or get out of this archive in the long run?

DM: In principle it’s supposed to be an easily accessible resource for anybody who’s interested. It’s as simple as sending me an email or giving the museum a call and making an appointment to come on up and see whatever it is you wanted to see. That’s sort of my hope for it, which I guess is pretty modest. We try to have it be as barrier free as possible. This is a silly example but there was an elementary school Spanish class and students needed to photograph themselves in front of a Latinx artwork, and I would get calls from the front desk from a student taking a Spanish class, and I would send them up. I maybe got ten students during the course of the week, and it was important to me that the answer was yes. I had just unpacked the work from the Lubeznik Center and had printed up the information from the database. Just something minor like that, you can come here as an elementary student, not an art major and you can access the collection; it’s a resource. It seems like students find it very memorable to visit here where you can essentially touch the artwork. I think that’s a very cool and powerful but simple thing that you can come here and even take selfies or whatever.

LI: That’s such a fun interaction. What a great assignment. Did you then have conversations with the students?

DM: Yeah, there was a procrastinating senior who came by and this was her last assignment and she was a future art major.

LI: That’s great! More professors should guide their students to the collection.

DM: You have to encourage the professors to come! It’s a long-term process of building relationships with people and encouraging them to bring their classes and have them feel comfortable with someone from the museum taking over their class for a bit.

LI: It can really open the student’s world.

DM: One-hundred percent.

LI: I understand you came to work at the museum while pursuing your PhD in philosophy. How do you approach the artwork and the archives through a philosophical lens?

DM: I tend to look at things with a big picture which is sort of a philosophical approach. I like to zoom out and see connections between certain things be it artworks, processes, or methods. I reflect about the larger implications of what a particular practice is. I think it’s impossible not to think about museums as peculiar places in the modern world that are intent on preserving objects for indefinite periods of time, which is a peculiar notion if you think about it, and it’s antithetical to how we do a lot of things. I tend to be reflective and also critical of certain things I read about or hear in academic circles or in art circles. I think museums and collections are more complicated and weird than people make them out to be.

Recently I had this philosophy of the environment class come to visit the museum and the collection and I was thinking, “man, I don’t really have that many artworks that deal with sustainability, the environment, and ecology.” But then what I did after I showed them the works in the collection, I showed them our storage area and I showed them our trash out the back of the building because I wanted to be excruciatingly transparent about the world of contemporary art. It’s this very weird place where we are showing and preserving trash, obsessively caring for what [would be] for anyone else waste. Packing it in cardboard and in crates and shipping it all around the world, disposing of those things, repacking them. The whole infrastructure of producing, displaying, and preserving contemporary art is a very perverse ecological problem. The class thought it was super interesting. I told them about a piece by Harold Mendez that is part of the museum collection, but the only piece that we keep is this bronze sculpture. But to install the piece properly you have to show it on a piece of marble and then you fill the copper sculpture with water and you put white carnations out every week, so it’s this sort of ongoing work that requires a fair amount of upkeep. It’s very hard because you have to get this very large piece of marble and put it on the floor, which is also extremely difficult because it is really heavy and it’s very fragile. When the marble was brought to the museum it was brought to us standing upright, so we had to get it flat. The people who sold us the marble basically laughed at us when we told them we have to get it flat. They said we would either crush one of ourselves or we would break it. But we managed to get it down.

LI: Your three-person team did that?

DM: Yeah, it was myself and my two coworkers and an art handler. Yep, (laughs). I feared for my life for a small second, (laughs).

LI: That’s a lot.

DM: But after the show the question became what are we going to do with the marble? Because it’s hundred of pounds and we couldn’t get it up off the ground. We tried to give it away or donate it, but no one would take it. So the only thing that we could do was break it into smaller pieces, so we all jumped on it. I actually kept a couple pieces, thinking I would change it into a coffee table or something, which I still haven’t done. The rest of the pieces I put out by the dumpster, thinking the garbage collectors would take it. But for eighteen months no one took it, and it just sat out there and sat out there. I noticed recently that it’s gone now. Hopefully someone took it and did something with it. But it became this fascinating thing, the way the piece lived on. We couldn’t dispose of it. That to me from an ecological, environmental perspective was really interesting, but also from a collections perspective as well. There’s tons of contemporary art museums that have way more works than we have here. We only have one or two works with these requirements for how you display them that are a little more challenging to fulfill, but MoMA or any of these places have hundreds and thousands of conceptual works, where to display them would require all of this incredible infrastructure to be activated. That raises all of these questions like, what does it mean to archive that work or to have it in a collection? To what extent is this work fully in our collection, given that we only maintain it in the form of this vase? Whereas this (gestures at the installation photo) is the work. It also has this durational maintenance aspect to it too. There are all these other aspects to the work that are not captured in the collection archive. SO many things that arise.

LI: There is a lot of invisible labor that goes into archiving.

DM: Yeah, those things really interest me. I’m interested in these things that are unseen or these structures that aren’t always visible. Part of my background in philosophy was to always be interested in the structures and conditions that make things appear how that appear, and make those conditions visible, because without them its worth doesn’t exist. Those are the things that I find interesting and that I think about and that informs what I do.

LI: Did you always know when you went into philosophy that you also had this interest in visual art? How did you come into this position? Did you seek it out? You seem very well-fitted for this position.

DM: I kind of fell into it by chance. When I was in undergrad I had a lot of different interests, and it was only over time that I realized what united all of those interests was that I was always interested in theory. I realized all of the different things I was interested in had in common was the theories being used to interpret them. I liked visual art and I liked film, writing, and all these different things. I realized that understanding the theoretical lenses and the philosophical concepts were what all of them had in common and I could never decide on one. Maybe in another life I would have been a film studies major and in another one art history, but philosophy is what allowed me to access them all at the same time. But I always knew artists and was interested in this kind of thing. Then someone I knew at DePaul forwarded an email that they were looking for a curatorial intern here, and I applied for it. I think I got lucky but I also think it helped that I was older. I think before the museum only had undergraduates be interns, maybe I was the first 28-year-old who applied looking for an internship. I think people realized maybe it would be interesting to have a different perspective than a younger student. The nature of grad school is it can go on forever, so I ended up hanging out for a long time and I was at the right place and the right time. Especially with the pandemic and people changing careers and totally rethinking everything. I had been here for a while and did a little bit of everything, so it was a natural fit.

LI: It was meant to be.

Chicago Archives + Artists Project: Case Studies in Collaboration serves as a site for new archive-inspired explorations, a directory of Chicago-based archives and collections, and a printed space where past artists, archivists, librarians, curators, and other collaborators can reflect on 5+ years of the Chicago Archives + Artists Project.

The book features two new artist/archive pairings with printmaker Ben Blount who spent time in the archives of Shorefront Legacy Center, and artist/poet Natasha Mijares who explored the Latinx art collection at DePaul Art Museum. Edited by Kate Hadley Toftness, with support from Tempestt Hazel, Christina Nafziger, and Persephone Van Ort. Designed by Matthew Austin of For the Birds Trapped in Airports.

The book also features writings from Oscar Arriola (Zine Mercado/Chicago Public Library), Sara Chapman + Dan Erdman (Media Burn), Sky Cubacub (Rebirth Garments), Meg Duguid + Michael Thomas (Culture/Math), Marc Fischer (Public Collectors/Temporary Services), Kate Hadley Toftness (Sixty), Tempestt Hazel (Sixty), Ivan LOZANO (CA+AP Artist), David Maruzzella (DPAM), H. Melt (CA+AP Artist), On the Real Film (CA+AP Artists), Jennifer Patiño (Sixty), Jessica Pushor (Chicago History Museum), Morris “Dino” Robinson (Shorefront), Robert Sloane (Chicago Public Library), Nell Taylor (Read/Write Library), Lauren Shadford (Voices of Contemporary Art), Darryl DeAngelo Terrell (CA+AP Artist), and more.

About the Author: Lauren Iacoponi is an artist, curator, writer, and arts administrator living and working in Chicago, IL. Iacoponi received her MFA from Northern Illinois University with a Certificate in Art History and her BFA from Columbia College Chicago with a Minor in Art History. Iacoponi is the Director and Founder of Purple Window Gallery, an artist-led project space coming soon to Avondale and the Director and Co-founder of Unpacked Mobile Gallery. Instagram handle:@lauren.ike

About the Photographer: Kristie Kahns is a photographer and art educator based in Chicago. Remaining close to her first passion of dance, she has spent over a decade as part of the Chicago dance community through her camera. She is also a dedicated teaching artist, creating analog photography programs for teens. She is currently a graduate student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, studying art education and administration.