“Beyond the Page” digs into the process and practice of writers and artists who work at the intersection of literary arts and other fields. For this installment, I interviewed Tanuja Devi Jagernauth — Indo-Caribbean playwright, dramaturg, organizer — about how her practices in theater, prison abolition, healing justice, and transformative justice interconnect; creating spaces for BIPOC theater-makers; doing mutual aid during and beyond the pandemic; and how she challenges systems of oppression and struggles for collective liberation through her work.

Tanuja and I spoke in May. We recognize that in the weeks since then there has been a broadened nation-wide uprising against policing and other white supremacist systems — an uprising sparked by the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade, Ahmaud Arbery, and innumerable others, as well as by other forms of anti-Black violence. We recognize that these racist acts are part of a long, systematized lineage. And we recognize that there have always been organizers and artists visioning and building against, beyond, and outside of that. We have decided to publish this interview in its originally recorded version because of its persistent relevance, including to ongoing conversations about creating and working in just and liberatory ways.

Find Tanuja on Twitter @tanuja_devi. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Marya Spont-Lemus: I want to start with gratitude. Because I feel very honored to speak to you more in-depth about your work — particularly around how your art and organizing intersect, overlap, inform each other, or maybe sometimes feel in tension. Though I’d mentioned a while ago that it would be great to talk about that, in some ways this feels like a strangely perfect moment to do so.

Tanuja Devi Jagernauth: Thank you. I’m definitely figuring all of this out in the moment, as I go.

MSL: How do you think about your work, and what feels most important to you in your work?

TJ: How to start exactly? I’m a lifelong writer, but I didn’t really own myself as such until maybe 2009, when I found my first writing coach, Minal Hajratwala, who developed a course called “Writing for the Chakras.” I think I was really asking for someone to give me permission to claim myself as a writer. Minal helped me to start to claim that, and I feel like I finally did when I went to the Voices of Our Nations Arts Foundation (VONA) writing workshop. It’s a multi-genre workshop where you spend a week with other folks of color who are trying to find their voice and create art. I finally felt surrounded by a community who accepted me as a writer. That was 2014, then I went back the next year.

Through this process of trying to figure out, “Am I even allowed to be an artist or a writer?”, I’ve been learning from queer, Black, Brown activists and organizers and from being involved in community work. My artistic practice has definitely been evolving and growing hand-in-hand with my politics and my organizing practice. And I think you’re right, it’s kind of the perfect moment to talk about this. As I was considering, “What is going to be the focus for 2020 — as a human, as a person trying to do work that is liberatory on a collective level?”, I decided I wanted to bring practices of mutual aid more into my theater work and really be explicit about it.

One thing I’ve been focusing on is a collective of Black, Indigenous, and people of color playwrights. At the beginning of 2020, I was thinking we’d continue meeting twice a month and see where we get in a year. But something about this moment of shelter-in-place and the pandemic has actually accelerated our process. We’ve been growing, in interest and numbers, which has forced us to really get our systems and practices into place. Saying all of this to say, I literally am trying to figure out how to be an artist and an organizer, and I’m learning all the time where those practices intersect or have wonderful overlap, and where there really is tension.

For me, the tension falls into time — and energy, and capacity. In terms of the actual politics, I identify as a prison abolitionist, I practice as many transformative justice practices as I possibly can, for resolving conflict and just moving through, but I am figuring out every single day where our practices can really be applied. I find myself observing how other people approach conflicts, whether with institutions or individuals, and wondering, “How would I assess their involvement, strategies, and tactics? How would I do it differently? What can I take from their example, and apply to the work that I do?”

MSL: Are there questions you find yourself continually returning to or interrogating in your writing? To what extent are those the same questions as in your organizing?

TJ: Yeah, absolutely. In the theater industry — probably in many industries — I think it’s so tempting to take on a project just because it’s been offered. I don’t have a theater degree, and my only formal training in playwriting comes through Chicago Dramatists — I got to take free classes when I was an intern and then on staff — so I’m coming into theater with this internalized scarcity model about myself. You know, “I’m not [blank] enough. Why should anyone take me seriously? I have to prove myself.” I’ve definitely found myself feeling I have to say “yes” to anything offered! In 2019, I was working on four projects at the same time! Every single evening was spent at one rehearsal or another. Or, working at a toxic fellowship at Victory Gardens, then running straight to a rehearsal, getting home around midnight, then doing it all again. Facing the consequences of that on my body, my mind, my emotions — and my friendships, to be honest — I realized that is not going to work for me. I learned I need to be selective about what I take on.

How do I assess what is going to be worth the time, emotions, energy? My personal criteria are different for theater — what I take on as a playwright versus dramaturg — than for organizing. As a dramaturg, I will absolutely take on projects written by someone whose project is to challenge systemic oppression in their work. They don’t have to be a person of color, though I would love to support other folks of color who are writing within a very white supremacist, toxic, capitalist industry. But say there’s a person of color who’s writing a narrative that reinforces systems of oppression — I’m not sure I want to work on that. I’m not the right fit. Unless the playwright is specifically saying, “I know the narrative of what I’ve created is whack. Can you help us realign it toward liberation?” [claps] Cool! I’m here for that. I also need theaters to be very explicit and aware of what they are asking for. A production dramaturg or new play dramaturg? This anti-racist coaching I’ve been asked to do, which I define as emotional labor and need to be financially compensated for? Let’s figure out how to make the compensation commensurate with the labor. Something I learned the hard way in 2019 — with help from Coya Paz — is that, yes, you can ask to make $15 an hour. Or $25, or $50, however you set that as an individual. If the stipend is limited, how many hours can you offer based on your rate? Different theaters will respond differently, and that’s okay.

As a playwright, I aim for my work to serve collective liberation. I would love my work to challenge systems of oppression and generational trauma. When I decided to exit the field of traditional East Asian medicine and come into theater, I knew there were certain things I needed to let go of — running a business, working so hard I had no time to write. But I wanted to take with me a practice of harm reduction and trauma-informed work; a general sense of body-positivity, which includes fat-positivity, sex-positivity; notions of self-care and community care. I want to bring allll of these frameworks into my theater work. I’ve been fortunate to have opportunities to practice these frameworks with theater collaborators, and experiences where they were not welcome. As a playwright, it’s okay if I never get a production, as long as I’m writing content that feels aligned with my values. And if and when I do get a production, there will be guidelines and agreements about how it’s produced, how everyone on the production team is treated, how I’m treated. For instance, until I see real changes at Victory Gardens, I won’t have a production there — I don’t believe in their model of making theater! I would absolutely produce a piece at Free Street Theater! I trust their method and process. I really am hoping that playwrights and dramaturgs and other theater-makers can recognize our value as individuals and seize our own power. You know, we are the means of production here. There is no production without our participation.

And as an organizer: Can we practice organizing that, yes, challenges systems of oppression, aims towards transformative justice and prison abolition? Really has an eye on anti-racist practice, and addresses environmental and climate justice? Is truly intersectional? Let’s try for all of that, whether we’re organizing within a non-profit context or in a more community-based, grassroots context.

MSL: Especially as a healer who works in healing justice, what role does creating — including co-creating — have in your own healing, coping, caring? And what role do you think co/creating has in a larger way around healing?

TJ: For me, healing justice encompasses that harm-reduction, trauma-informed, body-positive practice. But also healing justice requires collective practice, as it helps us figure out, “How do we not only transform the conditions we’re living in, but also practice self-care and community-care to transform the impacts of living in these systems?” I actually don’t love “healer” as a descriptor of myself. When I was an acupuncturist, I was there to facilitate a process, where someone could access their own healing — where, through my work with needles and herbs and my hands, I could maybe remove obstructions to their own internal healing resource.

MSL: I apologize for that.

TJ: Oh, no worries. But it’s interesting — I have found that collective mutual aid work and collective organizing, when it’s done in a truly horizontal way, is a healing experience.

I’ve been working with The Mutual Aid Mourning and Healing Project — a small formation of Kelly Hayes, Rabbi Brant Rosen, Nina D’Angier, Heather Lynn, Ashon Crawley, and me. We came together in March through Kelly’s facilitation, and our project has been to, essentially, gather and connect resources to those seeking those resources. So it’s a really simple model. We sent out a call for clergy members, death doulas, death midwives, social workers, and other kinds of therapists and support people, as well as a separate form saying, “If you’ve experienced the death of a loved one and would like to access these free resources, reach out.”

The process of making those connections has been healing for me, to see how many people have signed up to volunteer — people saying, “This moment in time requires us to look beyond our self-interest and be generous with our time and resources. If someone needs support, I’m here.” I’m absolutely inspired by that. It’s also been healing for me to work with this team, in the wonderful way that we work. We honor each other’s capacity. We check in with each other. I can ask, “I don’t really know what to do in this situation — can we brainstorm collective responses?” It feels very human, very forgiving. And I feel like I can be just who I am and that’s enough — which I haven’t always felt with different organizing projects.

MSL: Do you think anything else is helping make that difference?

TJ: Hmm. We’re doing it outside of a non-profit context. None of us are paid. I think we’re coming together driven by a belief in the power and necessity of mutual aid, of changing social relations for the collective good. I think because we have that shared value, and enough knowledge and trust of one another, we can move forward and do the thing we need to do. We don’t have a board to consider, or an executive director whose ego we need to stroke. [both laugh] Right? We’re just here to do the work.

Not all mutual aid work is conflict-free, or easy. I still consider it healing and beautiful and necessary, especially and even with the conflict. Because, to me, we build community through collective struggle, and I find, if I can’t struggle with someone, our relationship will stagnate at a certain level. And that’s fine; it’s just a reality for me.

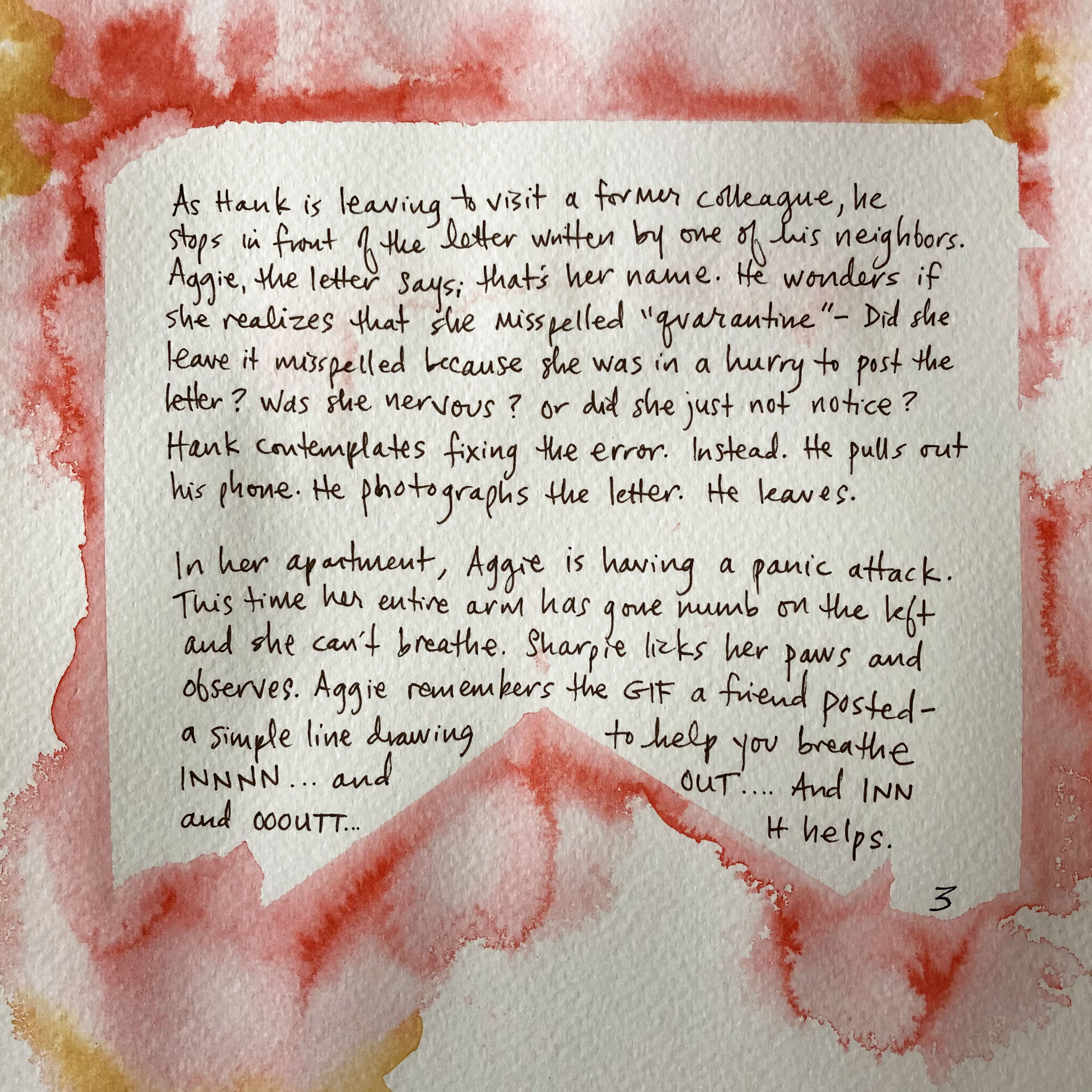

Images: “To Know A Neighbor,” a play by Tanuja Devi Jagernauth, March 2020. This micro play consists of six square images (one with the title, five with the play’s text) created to be read, not performed, and circulated online via Instagram as a “Contagious Closet Drama.” Each photo shows a page of the play, hand-written by Jagernauth in black ink on textured white paper, which she watercolored with rosy reds and rusty yellows of varying intensity. On the title page, the text appears directly over the watercolors; on most other pages, it appears inside abstract white shapes, each seemingly shaped from having been covered with paper and tape. A text-only version of the play is online here. Re-published courtesy of the author.

MSL: Acknowledging that you are the one in this conversation who knows a lot about transformative justice, I understand that an important aspect involves communities not turning to the state to resolve conflicts, but rather struggling together within their own community to do so. I wonder if there’s an aspect of that that you see as connected to your feelings about mutual aid work?

TJ: I think that’s right. The major pieces of transformative justice I focus on come out of prison abolition work for me, which involve understanding what you define “harm” to be — so let’s define our terms. “What is harm? Accountability? Healing? What does community mean for us?” I think getting a shared vocabulary is necessary for any formation trying to practice transformative justice. Then saying, “How are we going to prevent harm? When harm occurs, how will we intervene? How will we transform the dynamics that created the conditions for this harm to occur? If we can transform those dynamics — so identifying what those dynamics are. And then repair. What do repair and reconciliation look like?” I am drawing these four frameworks from a four-part video series by Tourmaline and Dean Spade called “No One is Disposable: Everyday Practices of Prison Abolition.” They break it down so clearly in a half hour that you could come away with these frameworks that they’ve so generously shared and start applying them now. That’s all I do with people who will let me. [laughs]

MSL: Something I’ve always admired is that you seem immensely values-driven and intentional in how you dedicate your time and energy — which you’ve touched on. And, at any given moment, you are working multiple jobs and endeavors across multiple spaces. While I’m sure aspects of that nourish you, how do you manage it and care for yourself? I imagine it can be draining, too.

TJ: As of the pandemic, I was not managing it well. I’m not saying — at all — that there are silver linings to the pandemic. What I will say, though, is when the shelter-in-place directive came down and my projects ended or were postponed, I was like, “Okay. I have time and space to reassess, to re-evaluate and commit to treating myself better.” This has been a time to say, “It’s a gift. Pivot.” I’ve been doing a daily yoga practice, meditation — commitments to my body, mind, and emotional state. As of April I have a full-time job with the Little Village Environmental Justice Organization (LVEJO). So I’m not available for multiple gigs anymore. I’d been working part-time at Free Street Theater — love them, so much — but my body was really hurting from working that plus gigs to string together an income I could live on. At this point in my life I’m finally aware of my limitations and honoring them. And I’ve committed to working on one theater project at a time! [both laugh] One, Marya!

MSL: But are you working only one role within the theater project?

TJ: Thank you! [laughs] The one thing I’m committed to is “Faust,” which I’m adapting through a devised process. Olivia Lilley and Prop Thtr are giving me the gift of just being the playwright.

MSL: What does playwriting for devising look like for you? If that process started before the pandemic, how has it shifted?

TJ: Playwriting as a singular playwright and devising as an ensemble usually don’t fit well together, right? But Olivia Lilley has created her own process, with Prop Thtr. First you pick the source text. For me, it’s a mash-up of Christopher Marlowe’s “Faust” and Goethe’s “Faust” — I’m choosing what I like of each and making a whole new source text. Then we do an eight-week workshop, where we do devising exercises with our cast, dramaturg, and director. It will be a musical so we’re also bringing in our composer, Alec Phan. The workshop process will be online and we’re all committed to making it up as we go. After the eight weeks, during which I’m taking tons of notes — and maybe proposing exercises or posing questions — we collectively break down the text, collectively pull out the themes. So it helps the playwright. Sure, I could look at the source text and come up with what I want to respond to, but I’m really interested in what other people think. And I know for a fact that this group will help analyze and develop this way beyond what I could do alone — I feel grateful to get to apply my organizing politics to this artistic practice. When I present a first draft to the team in December, they get to tell me, “You completely didn’t get it. Were you even in the room?” [Marya laughs] No, but I really am committed to coming in with humility and open ears. Did I hit the collective mark? It’s a necessary part, I think, of any collaboration. Then I’ll do a re-write, they’ll give further feedback, and, as of now, it will be produced in spring 2021.

In part because Prop owns their building, they have some interesting economic freedom. Olivia, as artistic director, is like, “We’ll do what we can when we can.” Also, I’m giving rights to all ensemble members and to Alec as composer of the music and potentially lyrics, so the people who created it will potentially benefit economically in the future, if others choose to produce it. That’s not something we see all the time.

MSL: Earlier you mentioned the BIPOC playwright group, and how you were trying to set up ways of working that also connected values and practices of your organizing and art. Is there anything you want to share about that process?

TJ: We created what I’ll call the BIPOC playwright collective around November 2019, out of a need for spaces beyond an external white gaze for BIPOC playwrights to just hear their work. From the beginning, I got feedback that I have never gotten from groups that are held and housed within predominantly white institutions. So I noticed an immediate difference in what could happen in the space, not only for me as a human but in terms of craft. The project began as that — a space free from an external white gaze. I say “external” to pay attention to this idea that we also have an internal white gaze — you know, if we’ve grown up within white supremacy, it’s there. Let’s keep it real. I cannot heal anyone’s internal white gaze for them, but I can help to remove at least the external white gaze. And we can collectively hold space for each other to create art. That’s it. That’s it! [laughs]

I’m really excited about the idea that we can create a structure for putting on our own readings. Eventually, if we can get funding or what have you, maybe we can produce our own plays — in the way we want, centering our values — so that maybe we can be a bit less dependent on predominantly white, toxic institutions of theater. And I’m very interested in ignoring this directive that I feel we get as playwrights, to “Just do you!” and to compete with other playwrights for limited resources. I think that model is done. Or rather, I’m done with it. [both laugh] I’m more interested in us coming together, making beautiful work, putting it up, and collaborating. It’s really simple. It maybe sounds naïve. I. Don’t. Care. [both laugh] I don’t care. Because I have felt and seen the consequences of putting myself in a position of dependence and gratitude for little bits of scraps of attention from predominantly white institutions. I can’t do it any more.

MSL: How did you find each other or first come together?

TJ: It was just a couple people at first. I had a conversation with Anjali Misra and we were like, “Okay, invite your people.” We’re not a huge group, but we do have core members — like Liz Haas, who I’ve worked with before, and Elon Sloan, who I hadn’t. Monique Rooker, Aidaa Peerzada, Olivia Lilley. A core group of us are setting up the systems and geeking out over, “What will be our grievance policy and grievance procedure? How are we going to resolve conflict when it occurs?” Later we’ll curate spaces for Black, Indigenous, and POC folks to present their work, and maybe we can host some panels and have these tough, real-talk conversations. But first, we want to make sure we’ve got our values and mission in place and our policies and processes solid so we know who we are before we start doing more external-facing activities.

Currently we meet twice a month, and basically it is, “Who’s got work they need to hear?” We’re very committed to having this open-door, big-tent policy for readings. If you are a BIPOC playwright and you have something you need to hear read amongst BIPOC folks, you can come get your feedback then go on your merry way. If you would like to organize with us and build, that’s an option but not a requirement. Because I don’t know of other BIPOC-only playwriting spaces, where you can just hear and get feedback on your work. For me, this is very much inspired by VONA workshops, where I got to experience that — it’s a beautiful, nourishing feeling. Then you go back out into the world and do what you have to do. And we have some similar struggles, but we do not assume that we all come to this space with identical politics. That’s why I think it’s important to have these containers and methods so we’re ready to hold whatever conflict comes our way.

MSL: I don’t know how to characterize it exactly, but…I have the impression that in a lot of your work you move to the tension, not from or around it?

TJ: Ohhhh. Right. [laughs]

MSL: At least that’s how I sense it, I think because it’s a way of working that I admire and believe is important. I feel like you’re very hands-on with tension, not only knowing conflict will arise but really dealing with it straight-on.

TJ: Oh, sure. I don’t know that I consciously say, “Let’s find the tension, let’s go!” [both laugh] But when it’s there, I definitely don’t like to ignore it. It stresses me out, frankly. What I’ve found is it really is a missed opportunity — for growth, learning, deepening. And, you know, I’m stubborn as fuck, [Marya laughs] and I’m like, “We could say this is a tension and problem and throw our hands up in the air and leave each other and never work together again — but look at what we’re missing out on if we don’t figure this out.” You know? Have I worked out every single tension and conflict with every single person in my life? Absolutely no. But when it’s really worth it, I think you have to. Other people might feel differently, but I honestly feel like it’s a sign of deep respect and love and care when you directly communicate, “Hey! I want you to know that I was hurt and harmed by this thing you did. I’m pretty sure you didn’t mean it that way. But I want you to know because I trust that you care about me.” Not everyone responds well when you confront something — and I notice. I really respect an organization that can hear and hold it when I say, “I’m going to share this thing I observed, and the impact it had on me. Then how I interpreted what I observed, based on its impact. And then, if you will allow me, I’d love to share what I’m asking for moving forward.” And I respect relationships that can hear that and hold that. So I’m truly hoping, because I practice that with other people, that people will practice that with me.

Absolutely there are scenarios where you kind of know the values of the people involved and you decide this is not a battle you can or should fight alone. But with the BIPOC playwrights, I’m like, “No, I do not want us to fall apart as soon as someone says, ‘I was really hurt by this thing you said in our reading group.’” I want us to be able to hear that and hold that and not shy away from the discomfort. Because especially when you’re bringing together people who are marginalized in society, we’re going to get into it. We hold so much trauma and internalized oppression. The content of our work is often rife with material that needs to be unpacked, so let’s get into it. The more we get into it, I think, the better the art will be.

MSL: You do so much to help sustain so many people, including me. I felt that way from the work we did together with Free Street, and even more with gatherings you’ve offered since the pandemic hit, like the “Rant Pants, Party Pants” and COVID Bake-off moments. You’ve mentioned a few people and groups who help sustain or propel you, and I’m wondering if there are others you want to name?

TJ: The other people who help me stay in it are my partner James Daley, my mom, and my dad. That’s my core unit. In terms of keeping my head screwed on straight, more or less, I rely heavily on Mariame Kaba, Kelly Hayes, and Truthout. Dean Spade, Tourmaline. I have my literary ancestors, Toni Morrison, Audre Lorde, Aurora Levins Morales. Every single disability justice activist I’ve had the honor of learning from — Ejeris Dixon, Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, Shira Hassan. You know, this wonderful community in Chicago — queer, Black, Brown activists and organizers and artists. Like, they are who I follow on Facebook. I make sure I see what they are putting out, first and foremost. When I feel particularly irritated or upset by toxic dynamics within the theater industry, I’m thinking, “Reground in your community and those who sustain you on a political level.” I’ve talked about Free Street, but 100% — every person on that team: Karla Estela Rivera, Coya Paz, Katrina Dion. I’m relying heavily on the political news content of The Hoodoisie. It’s another example of organizers and activists who are over it [laughs] and providing a really necessary, grounded news source in conjunction with the South Side Weekly! Like, thank you! You don’t get more grounded and rapid-response analysis than that, in my opinion.

I love Ursula K. Le Guin — another literary ancestor. I’m reading “The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia” right now, and she edited this version of Lao Tzu’s “Tao Te Ching.” I heard a podcast with Varshini Prakash, the ED of Sunrise Movement, who’s been reading a passage every day, and I was like, “I need to do that. I’m feeling a bit lost, let’s go back to the ‘Tao Te Ching.’”

Then there are yoga people I’ve found — thank goodness — who I feel are trying to decolonize yoga, not in the symbolic way but in the actual, liberatory way. Because I have a very complicated relationship with Hinduism and yoga, as a member of the South Asian diaspora. It’s been healing to me to find people who are really challenging the commodification of yoga and its cultural appropriation. Dianne Bondy, Amber Karnes, Colin Hall, Jivana Heyman, and Dr. Roopa Bala Singh are just a few.

And it still feels experimental, but now that I’ve had a chance to reassess, make new commitments, and slow down, pare down, I’m hopeful I can keep it up.

MSL: Are there any projects that, particularly in this pandemic moment, you want to amplify or call people to act on? Whether ones you’re working with or who’ve invited collaboration or mutual aid.

TJ: LVEJO is part of an initiative I love called “Farm, Food, Familias,” with Getting Grown Collective, Urban Pilón, Fresher Together, Amor Y Sofrito, and the #LetUsBreathe Collective. It came out of, basically, relationships. They’re asking for financial donations to help them distribute hot meals as well as herbs, wellness supplies, and medical supplies to families in Englewood and Little Village. It’s tremendous to see what they’ve been able to do with very few resources. Literally anything people can share will help another family be fed — maybe for another week or month. It’s a beautiful act of not only collective care but also harm reduction.

Definitely LVEJO in general. Along with other environmental justice organizers, we have this fight going on against Hilco, so if anyone feels moved, really pay attention and lend your voice and let the City know: “We’re not going to turn our gaze away from what’s going on.”

When the shelter-in-place moment started, Free Street’s Pulaski Park Youth Ensemble was in rehearsal for “WASTED,” their show about waste and how we see and treat each other, done in partnership with LVEJO. The young folks and Katrina Dion pivoted to figure out new ways of working that still reflect how Free Street makes theater, just online.

And I want to shout out all the mutual aid groups in Chicago, because I know folks are building systems and structures out of thin air. They’re doing — within weeks — work that normally takes a year. I want to encourage all artists of all shapes and sizes to consider participating in their local mutual aid group. Because we need all the imagination we can get and harness, to imagine beyond this moment, to imagine what the new world should and could be. If you’ve never done organizing or activism before, it’s a great opportunity to learn by doing. And I can’t think of anyone who should join in more than artists — people who do the impossible every single day.

MSL: That’s beautiful, Tanuja.

TJ: I’m really hopeful that everyone can just be open to new ways of doing the thing that we are actually trying to do. Maybe we can use this moment as a time to reflect and reassess and recommit to our deep desire to build a new world, by doing cultural work or artistic work or whatever it is. You know, the stakes are really high. So I hope it’s a moment of leaning toward that a bit. And you don’t have to do it alone.

Featured image: A digital illustration with four overlapping quadrants. In the top left-hand corner, three bees face a section of honeycomb. In the bottom left-hand corner, two people smile behind transparent face masks, each person holding part of a bag’s handle. The bag depicts a heart against a tree, with a broad circle behind that. In the bottom right-hand corner, a hand holds a pencil poised above the first line of a new sheet of paper. In the top right-hand corner, hand-written words float in the air (action, mutual aid, building, alignment, restructuring, bravery, struggle, ideas, collaboration), with dark blue, purple, and pink shading behind each. The left side of the illustration is yellow, the right side is blue, and they fade together to make green in the middle. Illustration by Teshika Silver (@astratesh).

Marya Spont-Lemus (she/her/hers/Ms.) is a fiction writer, interdisciplinary artist, and informal educator, who lives and works on the Southwest Side of Chicago. She is a white American of Polish, Irish, and Swedish descent. Find her work on Tumblr. Photo by Lucas Anti.

![[placeholder image]](https://sixtyinchesfromcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Quenna-Lené-Barrett_Headshot-300x99.png)