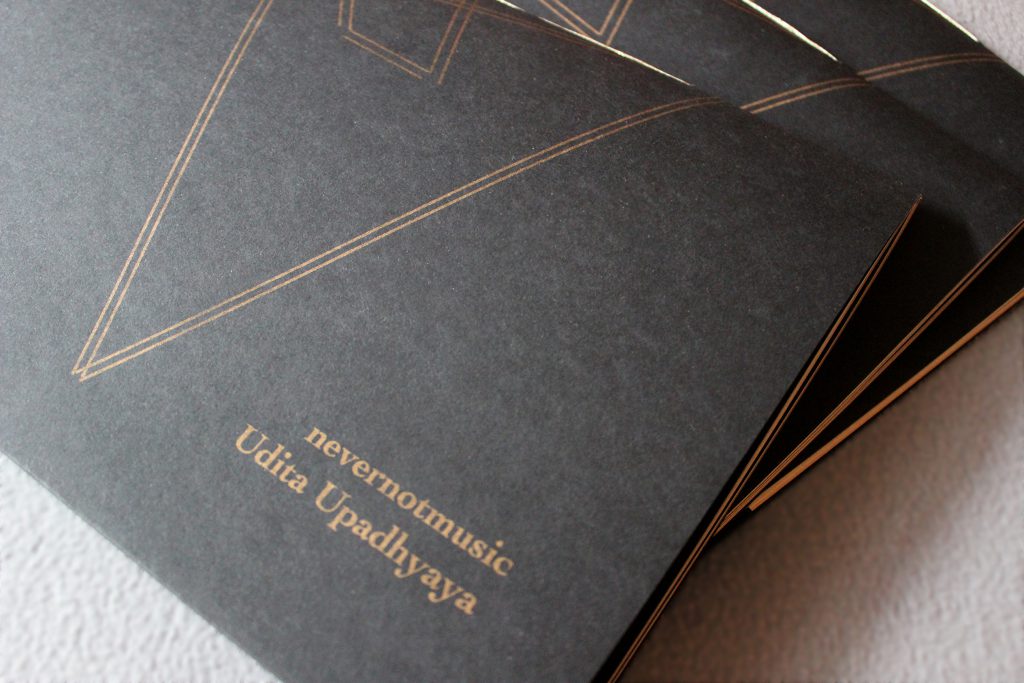

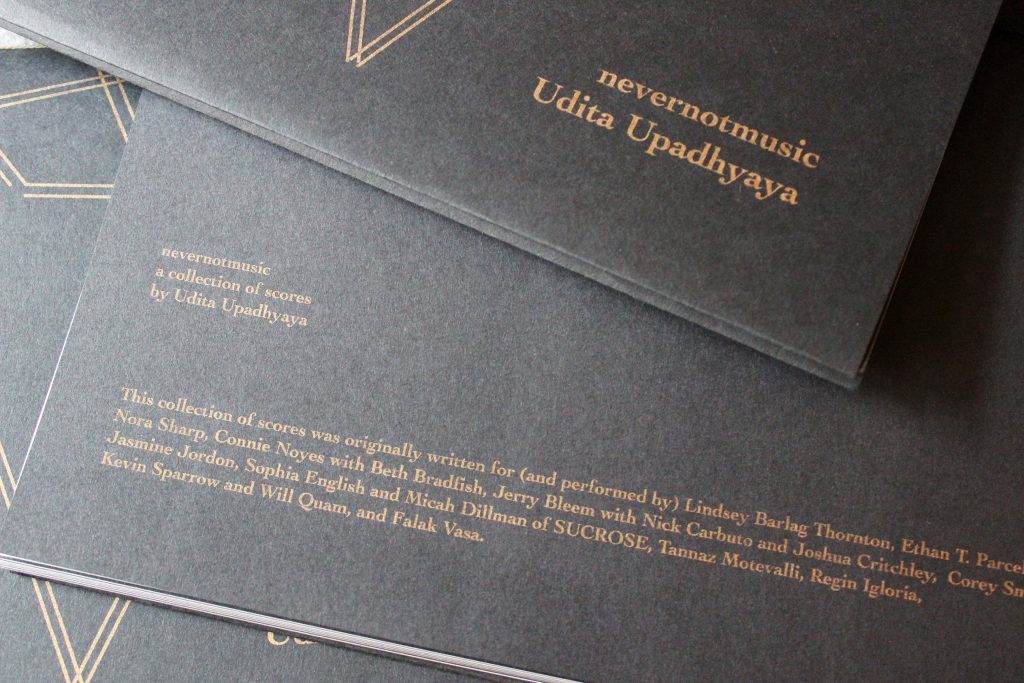

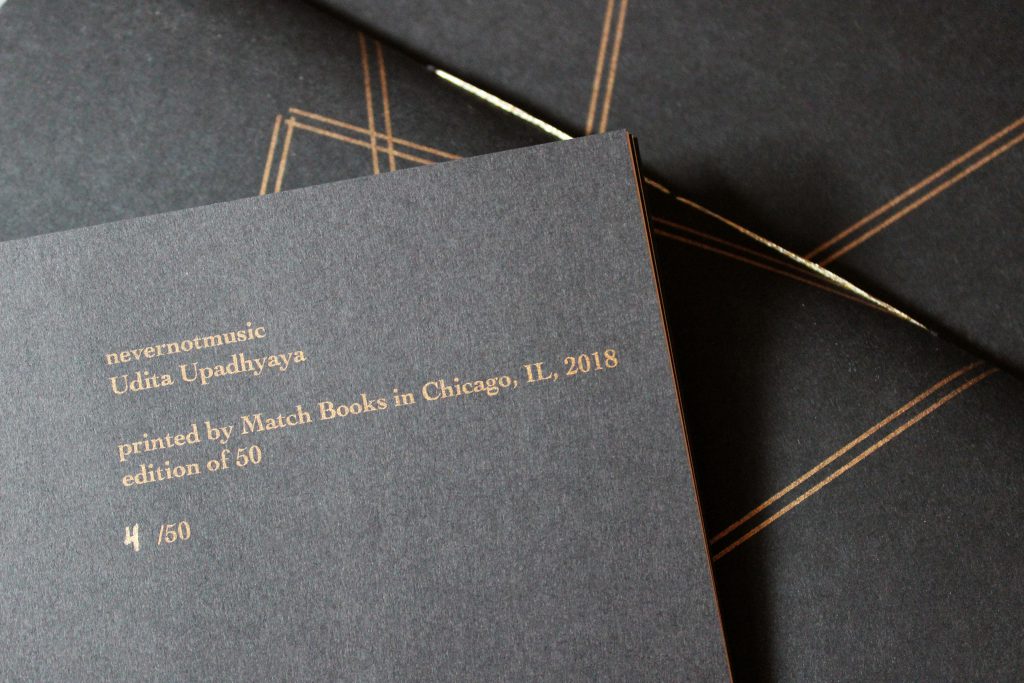

“Beyond the Page” digs into the process and practice of writers and artists who work at the intersection of literary arts and other fields. This interview is the third of three with interdisciplinary artist Udita Upadhyaya about “nevernotmusic” — a solo exhibition of scores activated by curated, collaborative performances — and her process of developing these scores into a book (the first and second interviews are online). After the book’s release in September, I met with Udita to reflect on the book, the process of creating it (and personalizing each copy), and the connection between music and grief in her work.

Get a copy of the limited edition book by contacting Udita. Find @uditau on Twitter and Instagram. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Marya Spont-Lemus: How are you feeling about Saturday’s book release event?

Udita Upadhyaya: I’m still processing, but I am feeling good. It was great to see the book in its final form. The book is really beautiful! I have not spent enough time with it yet, but it’s really beautiful. And the event was, too, and it felt very seasonal in this lovely way. It was very weird to be sweating when doing “nevernotmusic” things, because it was hot on Saturday, as opposed to the show at Roman Susan, which happened in the thick of winter. I feel like it was lovely to see the four activations of the same scores, six months apart. I’m especially thinking of Corey [Smith]’s for some reason. I really enjoyed his return to it because he was one of the 12 performers that had treated the score as a set of instructions in a very literal way. His last performance had started with, “The score that Udita wrote for me is ‘Unfold (into you)’, and da da da da da,” and it’s just so earnest and cute how he approached it, and I really like where he took it this time too.

MSL: This happened with a few of the performances at TriTriangle on Saturday, but Corey’s felt particularly marked by the presence of children. [laughs]

UU: Oh my gosh! I forgot about that. Yeah, there were no kids at Corey’s original performance.

MSL: I wondered how the presence of the child — sort of just walking up, and looking at him quizzically, and examining the cords — impacted others’ experience of the performance, and Corey’s of performing. At least from where I was sitting, it looked like Corey was smiling a bit or almost trying not to laugh at points, which I can imagine might have changed the way someone read what Corey was saying about love as compared to if he had been speaking and singing with a more somber expression. Anyway, there were several children on Saturday.

UU: The kids were definitely a very visible marker of how the book release was different than the show itself. Another was the space itself, which was also bare without the scores on the walls. I had a couple of people write to me before the event, “Is this kid-friendly?” and I was like, “Yeah, sure! Bring your kids!” It was pretty interesting to see, for example, Nora [Sharp] or Tannaz [Motevalli] perform around kids. When Nora said “fuck” I was just like, “Nooooooo!” [both laugh] But I guess I’m a little more precious about that word around kids than most other people.

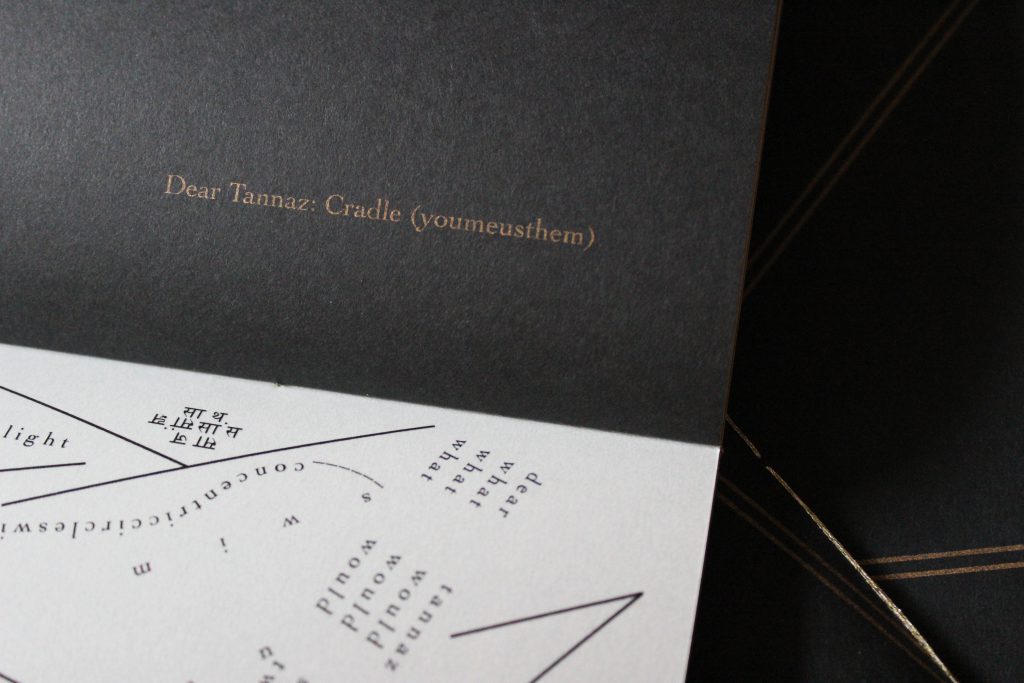

I actually had a really lovely moment with another kid. Right after Tannaz’s performance, this kid — one of my friend Ilene’s twins — came up to me and was like, “Can you tell me what just happened? What was that scene about?” And I was just like, “Whoa, okay. What do you think it was about?” We sort of came around to how life can be difficult, and Tannaz was on the floor for a lot of it, but then she carried the chair with her teeth, and “What does the word ‘cradle’ mean?” I feel like that conversation was definitely one of my favorite moments, which would have not happened with an adult. When an adult experiences performance art that they don’t get, they’re just like, “I don’t get it. Bye.”

MSL: Or they hide it.

UU: Or they hide it, right. Versus a six- or seven-year-old who’s like, “Can you please tell me what just happened, because I don’t get it?” Like, I’ll try! It’s probably not what Tannaz was thinking, but I’ll try. [both laugh]

MSL: What were some of the other surprising moments or favorite responses that you got to the evening?

UU: I feel like that was definitely the most fun, in response to the performances. For me, for obvious reasons, the evening was much more about the book, really, because the book is personalized for each recipient with a mini-score that is similar to the title of each of the scores in the book, or the original collection of 12. It was this mix of trying to think on my feet to come up with individual scores and then catching myself and being like, “Hey, closest friends, I cannot think about you right now. How about we meet when we’re scheduled to meet and I’ll write you a note then?” So it was sort of weird, for me, to have these little intimate moments within the chaos of the evening, to ask people, “What do you need now in your life? What’s going on?” and to think, “What should my mini-score for you be?”

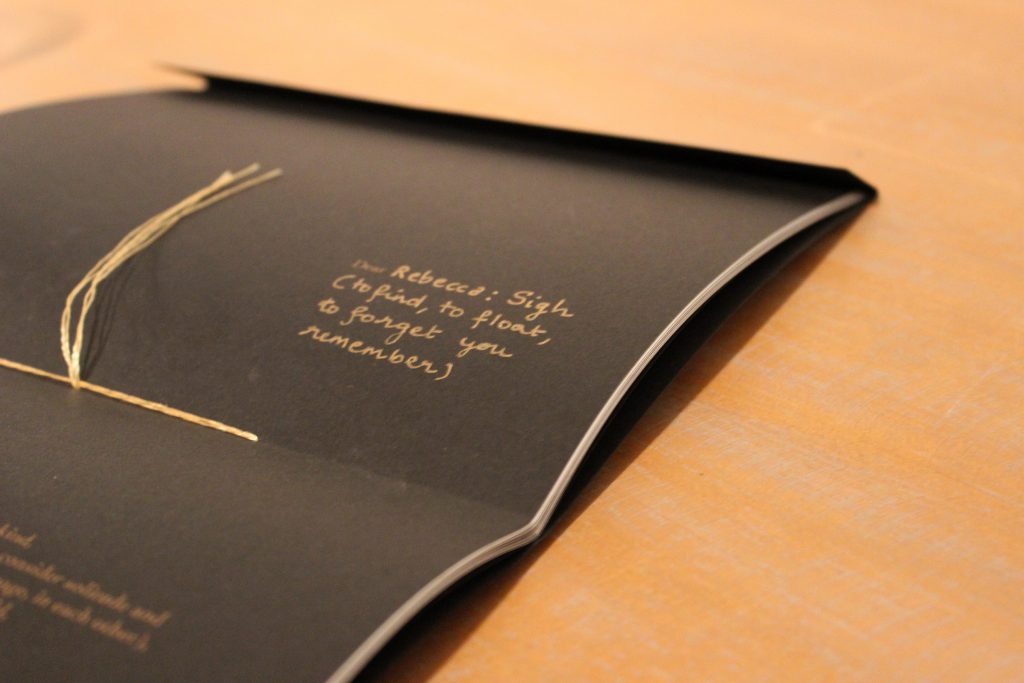

A really delightful thing was what I was calling “speed-art-ing” — like speed-dating but speed-art-ing — because I had to be like, “What’s up? Tell me about you,” in order to write mini-scores for people I didn’t know as well. One was for Rebecca, who I know through Meekling Press, who I’ve met a couple of times but I don’t really know. I think the thing I wrote for her was, “Sigh (to find, to float, to forget you remember),” because she said something like, “I forget everything when I’m put on the spot.” And when I wrote that mini-score to her she was like, “Oh my god! How do you know that I have been sighing a lot?” It was this really sweet moment of connection and care in the middle of the chaos.

Similar moments happened with people I didn’t know at all. I feel like I talked about this in the second interview, and I have been thinking about this: While I want all the books to find homes that are loving and caring, I also feel like, in this case, it’s always surprising to me when somebody’s getting the book that doesn’t know me at all. So writing personalized notes for people I didn’t know and was “speed-art-ing” with was funny. It was weird because I would ask, “What’s on your mind?”, and then sometimes in my head I’d be like, “Well, now we’ve been interrupted three times and I don’t remember what’s on your mind.” It was a fun challenge to try to listen deeply, to try and write a score in the middle of a very full social event.

I also had a lovely moment with this one kid — like fresh-human; I’m trying not to say “freshman,” so “freshperson” from DePaul University. Heather McShane [from TriTriangle] teaches a class there for incoming freshpeople, which I had visited two days before the release to give an artist talk and talk about the book. And this kid raised his hand, “How can I buy the book?” So I said, “Come on Saturday!” I think he was the first person to buy one. Writing a score for him was pretty special and weird and sweet, because I was like, “You’re really fresh and hopeful and I like it!”

MSL: Thinking about where the personalized mini-scores go, and moving to the book itself, I’d love to hear more about the letter that’s in the book–

UU: There’s actually 13. I’m kidding. [both laugh]

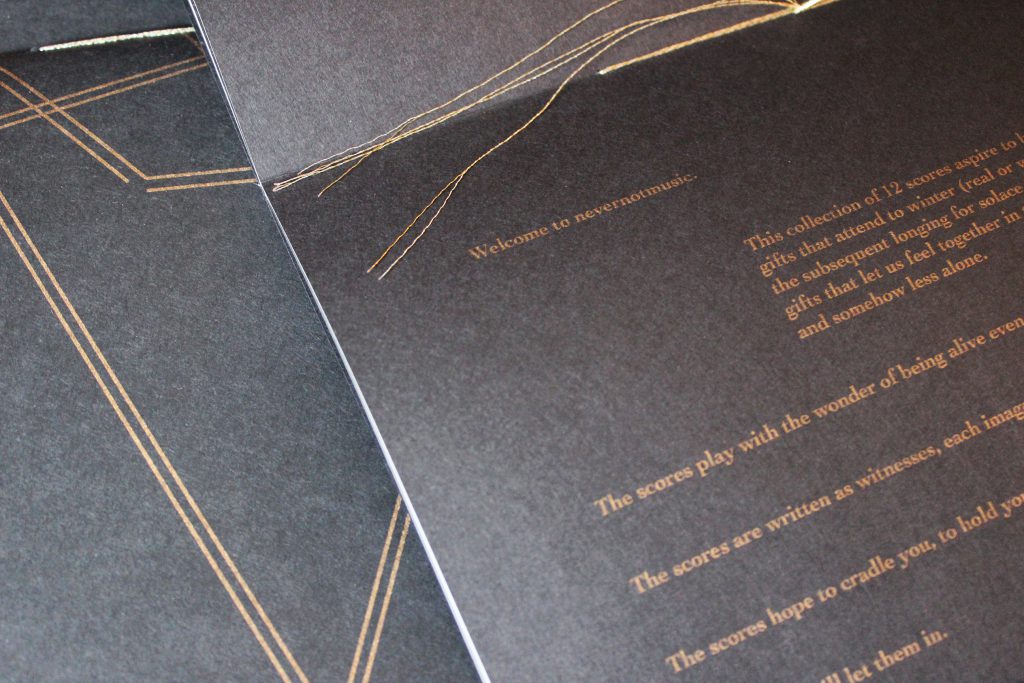

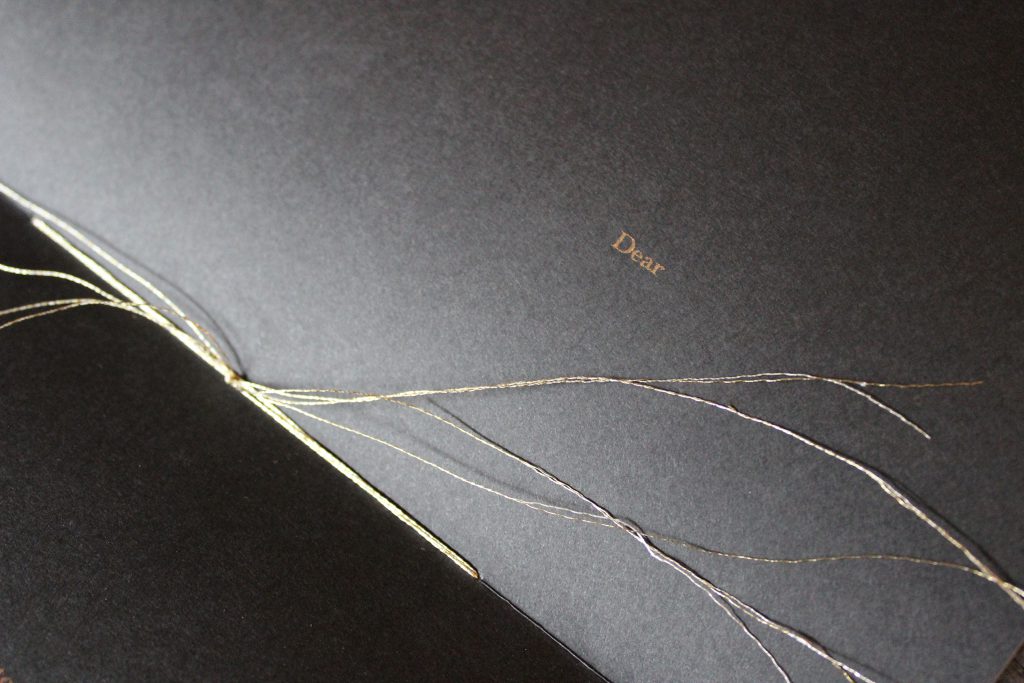

MSL: Yes, right. Every score’s a love letter! Then, at the centerfold, there’s your more general “welcome to ‘nevernotmusic’” letter, which is the one letter that’s not a score … until you personalize it and make it a score. We had talked before about how you were considering adding other features to the final version of the book, like where the “envelope” of the book makes you open to the centerfold, which then orients you to the project. But this element of having a “Dear [blank]” where you write a mini-score for each recipient of the book — I hadn’t heard you talk about that before. So I would just love to hear where that idea came from.

UU: Yeah. You cannot edit out what I’m about to say, even if that means writing, “You cannot edit out what I’m going to say.” I got that idea from my brilliant friend Marya Spont-Lemus. [both laugh]

MSL: Wait, really?

UU: Yeah! You know how I was struggling with what the edition should be and you said this thing about, “I really like that potentially you could know everyone that takes a book home with them.” And I was just like, “Well, watch me get to know–” [both laugh]

MSL: That was not a leading question. I actually had no idea that that conversation had anything to do with it. That’s really funny.

UU: Yeah, that’s why we didn’t talk about it yet, because it happened as I was looking over our conversation from the mock-up. And, I like writing scores! [both laugh] And I really like getting to know people, and I really like playing with words. I mean, it felt a little bit challenging in the chaos of the opening event, but since then — the release was a few days ago — I’ve been reaching out to the people that I know bought the book but didn’t get a personalized score to be like, “Hey, we gotta go get coffee because I need to write you that score! No pressure!”

But secretly I hate that that’s a blank until the score is there. Lauren [Zallo of Match Books] and I played with the idea of there being a line here so it would be a little more obvious — like “Dear [blank].” I mean, it really bothers me if there isn’t a personalized score. I’m not going to push for it too hard, because I don’t have, like, complete agency over who’s getting the books, but it is very important to me. And how I’ve been doing it is different. I finally gave myself permission to give whoever already has a score in the book the same score as before — like you just saw when SUCROSE dropped by. For them I’m just like, [laughs] “That’s your score! Or the title of your score. I’m not making up another one for you, please!” But it’s otherwise been kind of the same process as the original scores, just very shrunk into … like, if I don’t know the person, a 5-6-minute conversation. And really it sort of feels like writing back what they said.

MSL: Listening and reflecting back to them what you talked about.

UU: Yeah. And in those conversations — and we should have one, too, because I’ve struggled with yours — in those conversations there’s also a question of, “What do you need permission for? What is it that you’re not letting yourself do?” The reason I’ve struggled for yours is because I want to give you so much more than five words or whatever. [Marya laughs] Aww! No, but it’s true. When I’ve struggled, it’s been because I’ve known the person too well or something.

MSL: How many scores, then, did you write at the event? Approximately.

UU: Hmm. I have it in my phone somewhere. At the event, there were a bunch of books that were bought, but no one remembers who bought them. [both laugh] It’s slowly revealing itself because people are posting about it on Instagram and I’m like, “You have a book? Okay.” But I think I wrote [counting] — not too many — about five at the event? I still have a few “IOUs” in terms of scores, because I’m delivering books this week for people that were not able to be at the release.

MSL: My other question before we move on to talking about the book as an object is, what happens with any remaining copies in the edition of 50? Do they also get scores? How does that happen, or how do you think about that?

UU: Ideally, I think every copy gets a score. I feel like I’ve been doing math in my head since I saw the books. [both laugh] I’m just trying to figure out, “How many do I want to hold onto?” and “Who are the people that said they cannot make it to the event but want one?” All of those little things. About 35 copies are accounted for at this point. Match Books is also going to the Chicago Art Book Fair, so some of those sales may happen there. And I do want the book to live in artist book collections. At those, the copy is going to say, “Dear One,” and then I’m going to write something about my relationship with that collection. For example, with the Joan Flasch Artists’ Book Collection at SAIC, I have a dear connection with the space, and I wrote to Kayla Anderson to literally just say, “Thank you, because you were a crucial part of me realizing that the book form is already present in my work, and I just haven’t leaned into it in quite readily yet.” The endearment for the copy that is now housed at Joan Flasch reads, “Dear One: SINK (into every fiber, every vowel … each history).” So I can imagine the score for various collections to be similarly addressed to another person that feels similarly moved in or attached to that space. I think it would be more complicated if I were reaching out to artist book collections outside of Chicago that I haven’t been to, which I also want to do!

I don’t really like when the book goes out without a little note here, at the “Dear [blank]” part. Because it’s exactly what just happened to you — you miss that that’s there when you’re looking for it, because in the format of the book that is the blankest page of them all. One of the people I didn’t know that got the book actually posted a really funny Instagram video about how their page was blank. [both laugh] I don’t like that! The “Dear” feels very lonely up there without a mini-score.

MSL: So we talked in late May about the first mock-up, and a week or so after that I got a glimpse of a slightly different mock-up. I see aspects of both in this, and a lot of the changes I see are things that you were talking about wanting to change. But then there are also exciting surprises, like the mini-scores.

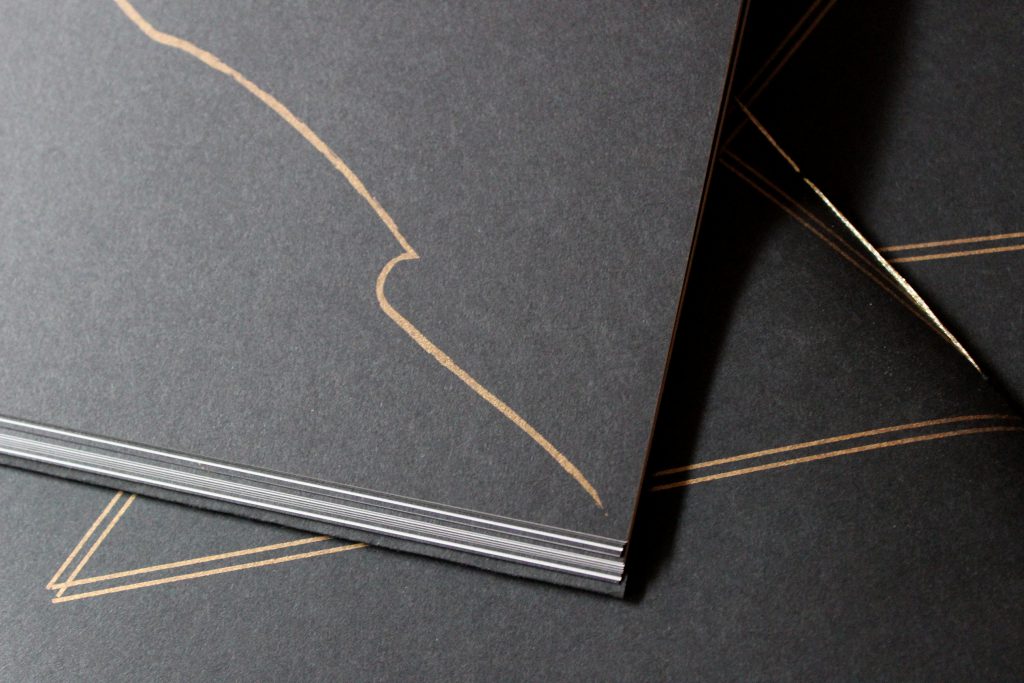

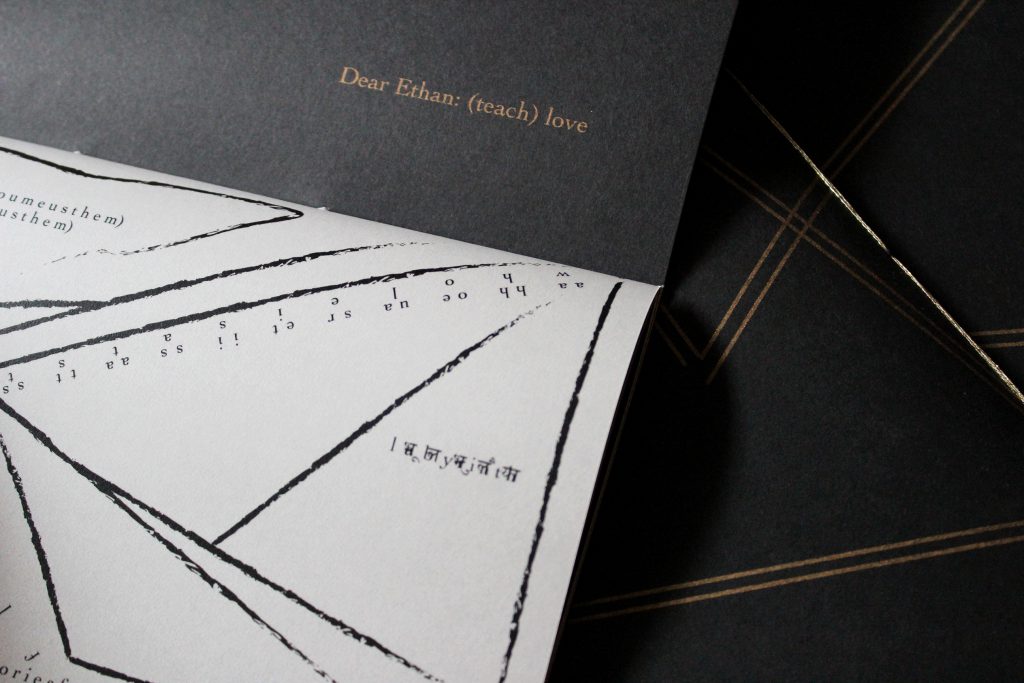

One of the other biggest differences is these lovely gold motifs or traces that are behind the vellum — the vellum the 12 original scores are on. You had talked in our second interview about that page feeling kind of blank or wanting to do something there — like maybe having a gold line continue through the book — and while, to me, this feels different than how I internalized that idea, it feels related. I’m wondering, where do these traces come from, how do you imagine us engaging with them, or how do they reflect or inform the scores? Just however you think about them.

UU: Yeah. I feel like I should start with how I have been feeling very emotional about the book in a way that surprises me. I basically cried the whole morning of the book release. Not for any other reason than “This is over.” I’m so going to talk more about kids going away to college. [Marya laughs] But this actually felt like the gestational period was over and the baby was, like, born and done. I feel like I haven’t looked at the book much because — I don’t know if this is like imposter syndrome or dysphoria or something — I cannot. I just spent too much time making it, and it feels really emotional.

And I think those gold scores behind the vellum were sort of a goodbye. They are responses in gestural form. So this [points at gold gesture], for example, is literally this [points at part of original score]. They’re all from there. It was me revisiting the scores six months later and also letting myself say goodbye to the scores. Because I haven’t ever felt this — well, I guess I have felt it in performance-based works, that they happen for this period of time and then they stop happening. It sort of felt like that feeling of the last show, or the last run. I don’t know if it’s mourning, but I’m definitely feeling like, “Okay, now it exists in the world, and I need to just let it go do its thing. I have no control over it any more.”

MSL: Does it feel different to feel that way about a physical object than it does a performance?

UU: I think I feel that way about all my work. This is probably not the best practice, but I don’t open up work that has been packed up after a show for a long time. Because I’m done. I think part of it is me not engaging in the healthiest ways of healing or getting distance. The book is still very much my baby and I love it and I can’t wait for people to read it and want it, but I also still know it as well as I did in February, so I haven’t needed to hide inside of it yet. And I think it was on Sunday where I was just crying with joy because I was so proud of myself. [both laugh] It was a bit like, “Wow, you made this thing! It’s beautiful! Good for you!” You know.

MSL: So there have been multiple kinds of crying happening.

UU: There’s been a lot of crying. And you know this, but I did get really awful news about somebody really dear to me passing away, so there is a grieving that preceded the book release event.

MSL: Like a cumulative sort of set of emotions are impacting? …

UU: Yeah. So somebody that was very important to me in my childhood passed away at the end of August, and September 2nd is the death anniversary of a really close childhood friend, September 5th is my grandmother’s birthday — in fact, we should talk about her for a second — and then September 8th was the release. And I literally, pun intended, had not had any release until the morning of the event where I was like, “And now I’m crying … about all of these things. This is happening. It’s finally happening.”

The reason I was saying that we should talk about my grandmother is because when I was looking at the two articles from before, I realized that we never actually talked about the title of this project. [Marya laughs] It has so much to do with my relationship with my grandmother, who was a musician — this is going to explain how I grieve — who died when I was about 12 or 13. After she died, I quit my music lessons, stopped really listening to music — it became this thing that I would only do to cry. I didn’t realize exactly what was happening, but if I was in the presence of live music, I would start crying. So I cannot be in a room of live music and connect to it. I have a lot of ways to dissociate it, which I use. But most often — especially if it’s Hindustani classical music or Carnatic classical music, which are the two from India — I will just sit there and cry. It’s ridiculous. Like, I will just cry for four hours. So I stopped going to musical things and really dreaded the, like, friend or date question of, “What kind of music do you listen to?” “Please don’t ask me that question. …” But I didn’t know what was happening, it was just something I sort of put aside.

And then a few years ago, I think my first year in Chicago, I was at a party and I was very drunk — which is why this happened, so I’m thankful for it. This person who was a pianist was asking something about playing tabla, which I used to do as a kid, and I answered him — because I was drunk — without that wall up of “Lalalalala, I don’t hear this question!” And I knew the answer. I still don’t remember what his question was and definitely not what the answer was, but drunk-me knew. Then he asked, “Oh, are you a musician?” and I was like, “No, I don’t even listen to music.” He was like, “That makes no sense.” And, again, because of the altered state, I ended up saying, “My grandmother is a musician,” and this person was like, “Oh, that makes sense. Every time you hear music you grieve her.” And it’s so funny, because I don’t remember what life was like, what I thought about my relationship with music, before making this connection, but there was a clear moment of things connecting, like the puzzle finally fits.

Since then, there has been more tenderness about this ambiguity about music but also more effort to step into it. But, I mean, I still have the muscle memory of that release, the same manifestation of grieving. On Friday — the night before the book release — I was supposed to go to Ragamala, which is this amazing thing that happens at the Chicago Cultural Center every September — a full night, 14 hours or so, of Indian classical music — and I just could not get myself to go. Because I knew there was grief already in my system at that point, and I would just sit there and mourn.

But after the conversation with that pianist, as I started looking at this more closely and started working with other people — Corey, Ethan [T. Parcell], Lindsey [Barlag Thornton] — who had music at the center of their practices in various ways, I realized that music was everywhere and I couldn’t run away from it. And I was finding melody and rhythm in everything. Because it’s not like I didn’t feel when there wasn’t music. But music worked differently for me. On Saturday when I was crying I basically went out and looked for, like, cheesy music to help me keep crying. [both laugh]

MSL: Like a valve sort of thing?

UU: Yeah. So the title, “nevernotmusic,” really came from my grandmother. I do think that the show and the book and everything about it is, in a way, an ode to her — you know, her memory, and me finally being able to gain an understanding of and track where grief lives in my body, and what my response is to that loss. I mean, it is also about other losses, but I can imagine an alternate life where, if she hadn’t died at that point, my practice would be almost entirely music-based, because I was doing vocal lessons and playing two instruments, and it was easier to quit because I was a teenager and I was a brat! But I feel like I wouldn’t have had this same reason to run away or even the same permission to run away from music had she been around. There would have been more pressure to continue — in a good way, now I can assume.

MSL: Before the interaction with that guy at the party, were you making scores or were you thinking of what you were making as scores? Or was that word also something you shied away from? I mean, because “performance scores” are a thing, but in a broader vernacular, when people talk about “scores” outside of sports —

UU: Oh yeah …

MSL: [laughs] — it seems more commonly to be about music.

UU: I think I was making scores without having the language for them. I have been thinking a lot over the last few days about this one specific studio visit I had with Amanda Graham, who I’m planning to actually write to about the book. She was a PhD candidate at Northwestern University who came to SAIC and sat with my work and said, “You’re writing scores!” And I was like, “Say more. …” [both laugh] I think it’s just about needing a community to see you, to hold you dear and reflect back what you’re working on and working through. I’ve had studio visits where Ernesto Pujol, one of my favorite people in the world and my mentor, was like, “You make work about grief!” And that is the most obvious thing ever — like, “What?! I should have known this!” — [laughs] but when he said it I felt like somebody had punched me. He’s very gentle, so not really. But I just sat there and started crying and was like, “Why would you say something so mean?” It didn’t make sense. Like how I didn’t know that what I was doing was scores, I didn’t really have the language for how art was a way of dealing with grief for me, until someone else gave it to me — or until someone else pulled me out from within my own score, or within the score of my practice.

MSL: When Amanda gave you the word “score,” how did it feel to have a word for that? If you remember. It sounds like being given the idea of grief had a visceral impact.

UU: That was horrible. I cried for a very long time. But in a good way. Everyone I told that story about grief to was just like, “What? This is so obvious. Why are you upset?” Which only added to it. Because it was like, “Everyone knows I’m making work about grief but me!” [both laugh] I think with “score” it wasn’t quite the same impact. I think it more became a discussion about score and notation, and I still use that language a lot. At the time I was talking a lot about wanting other people to perform what I was writing, or me wanting to not perform what I was writing, but also the scores needing to be embodied, to be performed. And “nevernotmusic” attends to a similar need of the writing requesting action, embodiment, performance. It does so maybe more directly since the scores are written for a specific person — with specific plans for performance. You know, the journey since that first score has resolved quite a bit. In “nevernotmusic,” it’s harder to call some of the scores “notation” because they are specifically to other people, but most of my other scores are score and notation. By which I mean, I have secretly or not secretly performed the score myself and so writing it is a notation of a performance that has already happened — but, having the score written down, it is also a way for others to re-perform the same score. Like if — and I am toying with this idea — your mini-score is “Marya: Rest” [Marya laughs] that is also something that I would hope would be notation for you for a different time as well, right? Or for me, right? To just be like, “At some point, rest.”

MSL: So how do you feel coming out of this extended project? Do you feel like you have any inklings yet about how this might impact your practice moving forward or how it has already impacted you? I know you mentioned you want this not to be the last time you work in a book form and that these scores are different than others you’ve made before.

UU: Yeah. I feel like I haven’t quite finished processing the project yet, because it has been just a few days. You know, it feels like it has existed since the time that my relationship with music and with my grandmother started. When I was making it, I didn’t realize how much the project had been gestating since like day zero. So I think that’s also where some of the sadness of this chapter of it being over comes from.

The same person, Ernesto Pujol, used to be like, “The work is ahead of you!” You know, like situating yourself in relationship to the work? Sometimes you as the person are ahead of it. You have agency and control, you are making the work. Other times you are fighting the work that wants to be born through you; you are struggling to make peace with the stories you are a vessel for. Some of my work was very difficult to make. I think it came at a very real cost. I felt like I was re-performing a lot of trauma and having a hard time. And, at the same time, that was the work that needed to be made, too, and my body couldn’t stop doing that till it was ready. Initially in response to the work that dealt more deeply and viscerally with trauma, I wanted to make work that was actually this — “nevernotmusic.” It started with me giving people what now I would call a “grounding kit” — with objects from all the senses and letting them use it — and then I would come back from that period and be like, “That didn’t feel like my work,” because it doesn’t talk about being angry and hurt and all of these important things. At that point Ernesto was like, “The work is ahead of you. You are here, and that’s the work you want to make over there.” I feel like with this project I’ve caught up to it, except I’m still a little bit behind because I’m like, “Whoa, I made that? Okay!” And this is probably where I need to gift myself a book, which I have not yet done and maybe will not do — like I need to let myself rejoice in the success of this or the kindness or the generosity of this.

All of that said, I am really, really excited about the book form. I am really, really excited about editions. I’m really excited about personalizing little things. I think I need this project to rest for a bit, and there’s other things that I’m working on that– It’s all related to each other, but it’s not the same. I think I kind of need a break from text. I think I’m more feeling a need for the large ink drawings that I’ve been working on to become more of an book object form. I actually have been thinking of them as not little books but boxes of little ink drawings. So I have all these ideas in my head. Most of them don’t have text, and I think part of it is that I’m texted out for a little bit. [laughs]

MSL: A quick clarifying question about the title “nevernotmusic”: I think in a previous interview, you sort of offhandedly said something like, “And Ethan’s the reason it’s called ‘nevernotmusic’ in a lot of ways.” Why is that?

UU: I remember saying that. Ethan and Corey are two of the most important collaborators in my life when it comes to the healing from music, in a way that’s different from Lindsey, who’s the person who was like, “Come! Let’s talk about music!” Ethan and Corey were like, “We will hold you through this,” as people whose primary practice is music — they both call themselves composers, at least, or “composer and performance artist” for Corey. Ethan and I also had very intimate conversations when prepping to write his score. I think he was talking about John Cage — or somebody who was performing a thing — and they sounded like they were singing, and Ethan said something about “never not singing” or “always singing, and never not singing.” And that became a thing, where at some point I was like, “Oh my god, Ethan, we are going to start doing ‘never not something’ for all of the scores.” I think I had “never not fighting” and “never not” something else. And eventually I was like, “This is ‘nevernotmusic’.” When I initially proposed the show, it was supposed to be called “Scores to Find, Scores to Follow,” which was fine for a proposal but I think all of us were just like, “Naaah. That’s not the name of this project.” So Ethan was definitely a part of arriving at this articulation of how music can nag us, follow us everywhere. I think all of my conversations about music have something to do with Ethan T. Parcell. [both laugh]

MSL: And, I mean, there’s the title, and there’s also the title the way that it’s written, which is that “nevernotmusic” does not have spaces between the words. There’s that thread of continuity, or something that doesn’t leave you, or something that doesn’t have broken space. I don’t know if that’s how you think of it, but that’s one way I was thinking about it. It’s a layer of meaning that’s more evident visually.

UU: Yeah. It really bugged me that, to create the event on Facebook, we had to do a capitalized “N” for “nevernotmusic.” I was just like, “I don’t like this at all!” The small letters with no spaces is definitely where the grief sits, you know? Depending on who you are in your relationship with music. For me, music and grief are so interchangeable. It’s not always a pleasant thing. I’m not happy that music doesn’t leave you. The scores have these feelings of “sigh,” “mumble,” “hum.” I think especially Lindsey’s score has all of these things where everything is music. Like the window is music. There’s this rhythm. Melody is in everything, rhythm is in everything. So there is definitely a feeling of gum stuck in your shoe, kind of, the feeling of grief — of its inconvenience, its, you know, stickiness. I think that that beautiful gold ink is not bright and shiny in quite the way it might seem. And, similarly, Ethan’s relationship with music is also really complicated. I mean, whose isn’t? But we sort of bonded around, “You made your life about this thing and I have spent my life running away from this thing.” It still has the same feeling of tenderness and rawness.

MSL: What do you feel like you’ve learned through this process? Acknowledging that it’s not really “done” — I think you used the phrase “rest,” like “it’s resting.” Or is there anything else that you want to share, looking back on it?

UU: Yeah. The happy tears. I used to make fun of my mom when she cried at happy things when I was a kid — because I was a jerk — but I was just like, “Who cries when things are happy? What’s wrong with you?” But I did, on Sunday. I think that part of it was that when I was at SAIC I was in Mark Booth’s class called “Text/Sound/Transmission.” And I remember fighting him every step of the way because I was like, “I’m not going to make sound work, I don’t like sound. …” In my head I was like, “Why am I in this class?” [Marya laughs] But I think, even at the same time, I was in that class because I knew, someday — like I was prepping for “nevernotmusic.” I wrote Mark an email after the scores were finished, being like, “This show exists because of that class.” I was prepping for it then.

MSL: But just didn’t know really? …

UU: I think I knew. I think I knew. Because I do feel like I took and did talk about that class as, “I’m taking this to deal with my hesitation with music and sound-based work.” And, even at that point, the way I could access it was text, which in many ways is still the way I’m accessing it. [laughs] I think I knew, but it still catches me off-guard how quickly it happened. Because that was … the end of 2015? So, in some ways, it’s like, “Wow, I knew in 2015 that in early 2018 there would be ‘nevernotmusic’.” I just didn’t have the language for it yet, obviously.

So the happy tears are definitely from the feeling of succeeding in the management of making the thing that wants to be made, and making room for it to be made. Because if I had my way with it, I would still continue denying the grief and denying the music, and it’s sort of like music succeeding and healing succeeding over not.

MSL: I mean, that’s a thing to — I don’t want to say “come to peace with” in one’s practice, but … that it’s good to be reminded of in one’s practice — that your work may know things that you know before you’re conscious that you know them. Or some combination of, “I see a thing coming, but I don’t know what it is yet, but I’m working on it, but also it will be different” — that sort of tension.

UU: Yeah. For me, learning has always been like, “I’m going to listen now, and let it happen when it happens.” I think that’s why I sort of subconsciously brought this book, “Living Beautifully: With Uncertainty and Change.” Pema Chödrön is really important to me in my practice of meditation, and just in life and being a human. The kind of meditation she teaches is a huge reason why I’m able to be an artist and able to work with trauma and grief and hurt, and fight through certain things in the world and my life. She talks about abandoning hope, or being in the moment, in this way that is kind of the opposite of how I want to be, and also kind of the opposite of how I think you are. Like, “Don’t take notes.” I don’t think she says that exactly, but when I first read her I just was like, “If this is important enough, it will stay. If this is important enough, and I am present, and listening, it will cycle back through.”

It’s kind of similar to how my word-of-the-day thing happened. You know, I’m not writing that word in the moment — “hungry hands” will show up six months later. Like, now I feel like my hands are hungry, because I want to make fiber things, I want to make ink things, and I want to cut things. So I think there is a feeling of gestational time for a project — trusting that — and I think this “nevernotmusic” project has definitely been the biggest example of not interfering with that gestational time. With other projects, because they’re in different stages, I think I kind of keep feeling like, “I think I want to interfere with this. I want this to be this other thing that it’s not ready to be yet.” I want it to be in college, at 12! [both laugh]

MSL: That makes a lot of sense to me about your work. It’s also interesting to me because it echoes something that Min Jin Lee — whose novel, “Pachinko,” I was telling you about earlier — said in relation to writing. This summer I took a one-afternoon workshop with her about interviewing for fiction. Something she said about her own process — and I think, to some extent, as a recommendation to us — is that she doesn’t record those interviews or even take many notes, but that when she leaves, what she’s thinking about is what moved her. And she’s doing those interviews for a different purpose — they’re not “archival,” for instance — but I thought that was such a lovely way of framing the interaction: paying attention to what moves you in a conversation.

UU: Yeah. [pause] It’s hard, it’s surprising hard, even as somebody who has done it in the past. Sort of the immediate thing to do is to be like, “Am I really listening to Marya if I’m not writing down what she’s saying, or if I don’t remember the name of the book she mentioned a while ago?” You know, this sense of accountability or presence within the dimension of this moment of time. I mean, I get that it’s valid – I don’t want you telling me a thing and I’m just zoning out and planning what I want to do tomorrow, and I’m totally guilty of that sometimes. But there is a different kind of listening that requires a different kind of labor, that also opens up room to be able to do that labor. And that is something that I really am excited to continue and to do better and to do more of.

MSL: Before we wrap up, how can people get your book?

UU: For now I am just going to say contact me through my website.

MSL: Well, thank you for everything. It’s been so great to go through this process with you, and I feel like I kind of knew you at the start of it, and now you’re my friend! [laughs]

UU: Yaaay!

MSL: That’s a really lovely, unexpected result of an extended conversation about a beautiful, complicated work that feels — I’ll let you say that it’s “resting” now, but it also feels not over to me. I can’t wait to see what’s next!

Featured image: Udita Upadhyaya at the book release for “nevernotmusic,” at TriTriangle. The artist leans over a table, looking down as she writes in gold pen inside a copy of her book. Next to Udita is another copy, open to its centerfold, where gold thread is visible. The artist wears a light-colored, textured sweater. Photo by Caleb Neubauer.

Marya Spont-Lemus (she/her/hers/Ms.) is a fiction writer, interdisciplinary artist, and educator focused on teen creative, leadership, and professional development. She lives and works on the Southwest Side of Chicago. Follow her on Twitter and Tumblr.

Marya Spont-Lemus (she/her/hers/Ms.) is a fiction writer, interdisciplinary artist, and educator focused on teen creative, leadership, and professional development. She lives and works on the Southwest Side of Chicago. Follow her on Twitter and Tumblr.

![[placeholder image]](https://sixtyinchesfromcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Quenna-Lené-Barrett_Headshot-300x99.png)