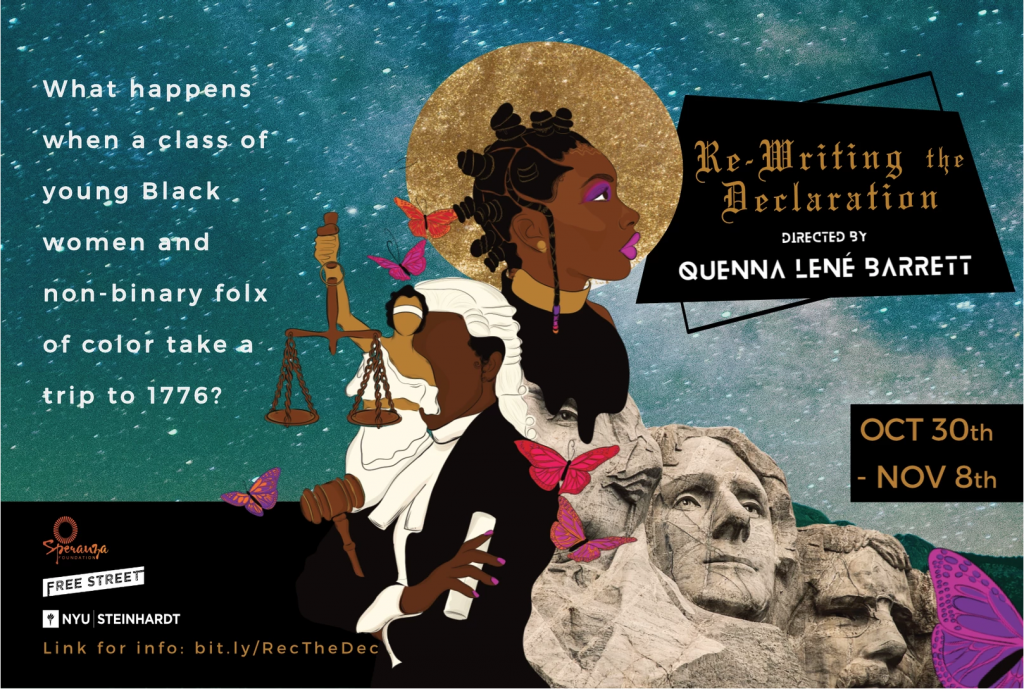

“Beyond the Page” digs into the process and practice of writers and artists who work at the intersection of literary arts and other fields. For this installment, I interviewed Quenna Lené Barrett — actor, educator, writer, director, activist, scholar, and lifelong Chicagoan. We spoke in late November about her ongoing project, “Re-Writing the Declaration,” and its recent production; how her many forms of work inform each other; and using applied theater as a tool for civic participation and Black liberation.

Follow Barrett @quennalene (Twitter, Instagram) and @quenna.lene (Facebook). This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Marya Spont-Lemus: After getting to experience aspects of Re-Writing the Declaration as a project over the last few years, it was extra exciting to see the production of it earlier this month. Now that a few weeks have passed, how are you feeling about it?

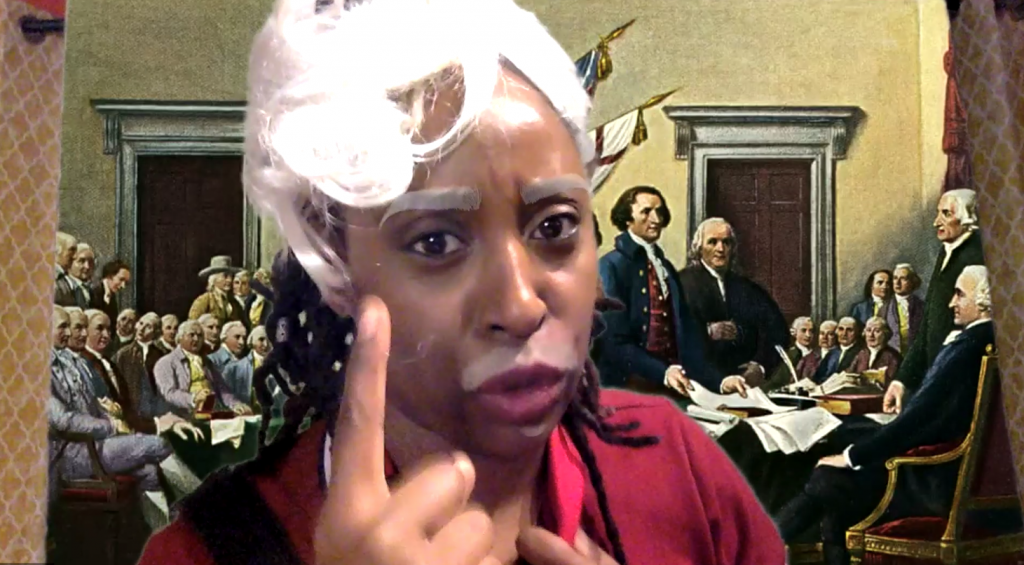

Quenna Lené Barrett: Still feeling really good! I was directing two shows at once — Re-Writing the Declaration and another one, in this virtual format — and then had other projects come up. These past couple weeks, I keep saying, “I’m in recovery.” Part of me is like, why is it taking so long? Usually, I bounce back sooner. But also we’re living in a pandemic, and I was doing a whole lot at once. So I am still living in the relief that it all went well, that people came and enjoyed RWTD, that even though the process was different than I anticipated we were able to pivot and pretty quickly create this thing that I think the ensemble is proud of and that I am certainly proud of.

And to go through the project’s history, briefly, I’ve had the thought to “re-write the Declaration” since about 2015. In 2017, I began exploring what it might look like as a piece of theater while I was in residence at the Santa Fe Art Institute. Questions that have been guiding the project from the beginning include, “How can a place truly ever be free to all? How can we resist oppressing another in a quest for freedom and independence? How might the re-writing of such a document include the voices of the multitudes? How can people not included in this nation’s founding (re)claim this is a space where we belong?” I was selected as one of the In/HOUSE residents with Free Street Theater in 2018, and that summer I started a doctoral program in Educational Theatre at NYU. I’ve been developing this project artistically and academically through those entities since — both of which co-produced the show, along with the Speranza Foundation. And 2020 provided the perfect storm for Re-Writing the Declaration to surface.

MSL: How did your past research inform this iteration? I’m thinking, for instance, of your public workshops at Free Street Theater and their Storyfront, as well as your residencies and doctoral program. And how did you balance that research with what the cast as individuals and a collective were bringing into the production?

QLB: The point I realized that this needed to be a devised piece — and not just me taking all of that research and writing a play — was probably two or three weeks before rehearsal started. The research process was always in this land of the transformative paradigm. Devised processes take away some of the traditional power structures in theater-making. So I knew that, even though I was the director, I really wanted what was happening to come from the ensemble. Since I had lost the ability to continue the in-person workshops — where a broader public would inform what the play looked like — I knew that this ensemble really needed to be making those decisions and that I was just helping to shape and mold. I didn’t want to interrupt what their visions or ideas might be with my own preconceived notions.

In the half a draft that I had before we started rehearsals, the play had seven characters who exist across time, and the central place was this beauty shop where things happen by magic or by connection to a spiritual realm. But, with this new process, I tried not to give the ensemble any of that. I went back to the project’s beginning research questions and tried to start a devising process from there. But a few days into rehearsals they were like, “Um, all this ‘research’…?” Like, “Where is your stuff? That you wrote?” [laughs] They wanted to be directed! And I was like, “No, this is devised. I’m going to give you prompts and questions and have you do the stuff.” I had to really navigate that tension, between giving them what to do and creating the thing together from scratch.

So one day I gave them access to all my materials — like transcripts from the workshops, videos, a survey I conducted, and a draft of my dissertation’s topic review. I was like, “Cool, you group of people look at this set of materials and artifacts, you group of people look at this other set.” What’s fascinating to me is that there were ideas from that work that the ensemble was super intrigued by and thought we would keep, but ultimately didn’t make it into the final play. One piece that did come all the way through was the game “Wheel of Restoration.” The original version had come out of a workshop I did at the Storyfront. Deanalís Resto (who was in the recent production) was part of the group that made it, I think along with Kristiana Rae Colón and Ky Baity. I had gathered a group of Black artists and artists of color for several days and we just played around with the script and content that I had at the time.

So my research created a foundation for the devised piece, in I think a strong way. Because I had done all of that labor, I was able to answer a lot of questions — not necessarily about the Declaration document itself, but about what this sense of imagination could look like or what could inform it. And there were certain things that I just knew — like that the play would be participatory — but this configuration of people figured out how to make that work.

MSL: How did you find the cast, or how did you all come together? Had you worked with each other before?

QLB: We put out a call for auditions two or so weeks before rehearsals needed to start. This thing moved so quickly and I was [laughs] so afraid that we wouldn’t get the ensemble we did. I blasted it on my social media. The doctoral program I’m in sent the call to a listserv that includes students and recent grads. Mostly between those, about a dozen folx submitted. With the final eight, I did two callbacks then group auditions over Zoom. I invited each to teach the group something — which I always find useful for devising processes, like, how you interact with the group, how engaged are you going to be. And I just knew, cool! This is the right crew!

Deanalís Resto I had worked with before, as a performer. We were both in the same performance company at one point, For Youth Inquiry (FYI), which is part of the Illinois Caucus for Adolescent Health. I’m still part of it; they are not currently but have stayed involved in other ways. Simone G. Reynolds, who is a student of ours [laughs] from several years ago, was in the first theater program I started when you and I were at the Arts Incubator. Sabrina Lynne Sawyer was a former intern at the Goodman, my current job, and had been a part of a Sojourn Theatre project before I became a part of it. We found that out in the internship. I went to high school with Zanneta Kubajak! We did theater together 15 years ago or so, which is amazing. And she had just given birth days before she submitted for this! She lives around the corner from where I live, in Chatham. Asha John, Kourtney King, and Andrea Ambam are all the New York folx. I had been in classes with Asha throughout my time in the Educational Theatre program. She completed her masters there in 2019. Kourtney’s a new student in that program. Andrea’s a graduate of the Art and Public Policy program at NYU Tisch. Cree Noble did the performance studies program at NYU, but I knew her through a mutual artist friend, Will Green, who connected us when she moved to Chicago. Cree actually had come to one of the RWTD workshop days.

So the cast was this combination of folx from these places and communities in my life. And it was a cross-country cast in a way that would not have been possible if we had done this in person.

MSL: How else did the change of circumstances impact this iteration or your initial idea of the process?

QLB: The initial proposal was that I would finish conducting these in-person workshops — where I gathered material with people, who I paid for showing up — in particular in communities of color, queer communities of color, low-income communities of color. Really the folx most impacted by the justice system. I would ask, “If you were to re-write the Declaration of Independence, what would you include or consider? What’s important to you?” I even did some light devising with those groups to think about, what do the participatory actions in the play look like? What is it that we want to invite people to do, in the theater space, together? How are we using the theater — the play space — as a site for active change? As opposed to, “Come watch this thing, feel a certain way, then go think about it and have discussions,” which is often what theater does. But part of the thesis of this project is, can the theater be a space where folx can participate civically? That was generally the original plan. I didn’t want to write the full play until after I had finished that phase of the research, where I was facilitating the workshops and gathering data from people.

Then the pandemic happened. We were slated to do something in-person with Free Street this fall, and Coya Paz, Artistic Director, asked earlier this summer if I wanted to pivot online. And I really didn’t want to. I think I was also just tired from the uprisings and all of the everything that was happening and was like, “Doing it online seems counter to what the piece wants to do and wants to be.”

MSL: In general, and in considering that context, how did you decide which parts of the online production would be performed live online, and/or involve audience input, and/or be prerecorded videos? How did you think about those priorities and that balance?

QLB: Parts of the building of the participatory moments had to do with the way I’d think about them even if we were in person. So like scaffolding — which we know as educators — but specifically thinking, how do you get people really excited about participating? Because it’s a hard thing to do! Most folx are not performers. They come to watch a thing, not to do anything. [laughs] That takes very careful consideration. At FYI, the For Youth Inquiry Performance Company, we think about it on a scale of exposure: How do we introduce things at a lower exposure and then scaffold it up to a higher exposure? For RWTD, as a director, I thought about it in those same ways — but we also had to think about the platform we were on. What does the technology of Zoom allow us to do? How are people coming to the show already using it? And what would be an exciting way to engage with it — so that it doesn’t feel like the same old thing they’re used to?

So, both of those things impacted how we thought about it. We had to get people interacting in small ways that they were used to before we could have them come onscreen. And how do we ratchet that up so that it feels fun and exciting by the time that we do ask them to come on-camera? For those who will want to.

Initially, as we were devising, we thought the games and the healing journeys would be choose-your-own-adventure, where folx would choose different breakout rooms. We thought the healing journeys and the altar would be prerecorded as well, but at a certain point realized, “Oh, no no no no! We need to be there, in presence, with people.” That felt really important. Especially when we were in the middle of election season, and we were sort of healing ourselves from lots of different things. So we didn’t want that healing moment to be a passive act. We wanted to be really intentional and present with folx.

The technology also limited what we could do. We needed to be in “webinar” mode to control who’s onscreen when or talking. There’s just so much opportunity in a regular Zoom for folx to come onscreen in unintentional ways, and we wanted to be mindful of that. But in a webinar, you can’t do breakout rooms — and we didn’t want anyone to miss out on any fun! In terms of the prerecorded videos, we thought we might do some of those portions live, but, again, the limits to technology. The cast wanted to do the “You Name It!” spoof live, and I was like, “Y’all, we can’t hear you if you’re all singing at the same time on Zoom.” [both laugh] It just doesn’t work. So that had to be prerecorded. What else?

MSL: [laughs] The Maybelline parody?

QLB: Just so funny! Those “commercials” weren’t intentionally part of the project at first, they were from creative exercises I had the ensemble do to think about how we could use the platform. I was like, “Devise something in two minutes and you can’t be in a standard Zoom frame and you have to think about lighting.” Those “commercials” were birthed out of one exercise. I was like, “These are going in the play, y’all. This is funny as hell.” [both laugh] Once we realized we wanted it to be a commercial, we knew that it needed to be filmed.

Also, from the beginning, we had to think about how prerecorded content would be placed so that the actors could have a break or change costume. So the videos were also strategic in that way.

MSL: This production ran from October 30 through November 8. I was only able to attend the Friday morning performance (alongside a class of really thoughtful seventh-graders!), a few days after Election Day. Thinking about how the various modes and moments of participant interaction impact the play itself, and especially given its timing, how would you say the play differed from performance to performance?

QLB: We always knew, even with the in-person version, that it would happen around election season. We were always trying to think, “What does that mean? And how can the play support people in different ways?” I’d say that post-Election — and maybe this is just driven by the cast [laughs] — there was a more buoyant energy from the audience. I don’t know if there was much of a qualitative difference from pre-Tuesday and post-Tuesday. Probably.

Overall, I think people just engaged in the different ways they do. Some nights the chat was more alive than others. Sometimes folx were really ready to hop in and turn on their cameras, and some nights the cast had to improv until folx would do that. [both laugh]

I think what fascinated me most about audience participation was in the game “Wheel of Restoration,” where people get to re-write the grievances. We asked folx to amend, keep, or abolish the Declaration’s grievances, while thinking about a 2020 context, in terms of who would we be stating these grievances of. But something really interesting happened. Folx would often say, “Oh, I don’t like that.” Well, that’s exactly the point. It’s a grievance because it’s a thing the king was doing — because it sucks! But instead of keeping the grievance because it still applied — because people in power are still doing that same thing — the participants would just reframe it to be a bit more specific about who the acts of harm were being perpetrated against. Which was cool, but essentially they were agreeing, but not thinking that they were agreeing, which was funny.

Then a couple of times, when folx landed on a grievance that they wanted to abolish and write something completely new, they opened it up to the group. And they said, out loud, “Well, it’s for everybody, right? So I don’t want to be the one making the decision. Let’s all write this thing together.” And I was like, “Yesss!!!! That’s the whole point!” [both laugh]

![Image: A screenshot from a live portion of “Re-Writing the Declaration,” showing the results of a participatory “Mad Lib-eration” exercise from the October 31, 2020, show. The image shows an excerpt of the Declaration of Independence, with audience-provided words subbed in “Mad Lib”-style for select portions. The title reads “Mad Lib-eration” in purple, futuristic lettering, superimposed over a vertical, blue-green galaxy background, with a grey landscape-oriented slide visible behind that. Within a gold box, the body text reads (words asterisked here represent the replacements): “In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for *Freak’um dress* in the most humble terms. Our repeated Petitions have been *went* only by repeated injury. A(n) *candy corn* whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a *lively* people. Nor have We been wanting in attentions to our *rancid* brethren. [paragraph break] We have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend an unwarrantable *nose* over us. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our *love* and *hate* here. We have appealed to their native *Burger King* and magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the ties of our common kindred to disavow these *cashews*, which, would *singularly* interrupt our connections and correspondence. They too have been *small* to the voice of justice and of *supercalifragilisticexpialidocious*. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the necessity, which denounces our *test-phobia*, and hold them, as we hold the rest of *Mr. Bubbles*, *colonizers* in *everywhere.*” Image by Quenna Lené Barrett, using design elements from Naimah Thomas.](https://sixtyinchesfromcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Quenna-Lené-Barrett_RTD-Mad-Lib-eration_10.31.20-1024x640.png)

MSL: What kinds of responses have you gotten to the Re-Writing the Declaration project as a whole, and particularly to this production? Whether from attendees or the performers or other people in your life.

QLB: People seem to have really enjoyed it! I got a lot of positive feedback from the Ed Theatre program I’m part of. The director wrote a note to the entire community, as did a couple of my professors. My mom texted that she enjoyed it. So did my uncle. I had family members come who have never seen my work, which is cool because this provided a different type of accessibility. And I think folx really were appreciative or surprised by the interactivity? Both how we used the Zoom platform and the questions we were asking. And that it felt playful and joyful and celebratory even though we were dealing with this subject about harm and violence, in many ways. That we were able to infuse the play with humor and poignancy, and that it got folx to thinking. Some people said, “I’ve never had to consider or look at this document! Then I read these words you put in this audience poll. What does this mean?”

Many of the cast’s reflections were about the process. I think they enjoyed doing the show altogether, but really they talked a lot about having not had spaces like this as an artist of color, as a woman or non-binary person or a Black woman — like about not having been in rooms where it was just us and how powerful that was. For me, that also feels like the work. How are we transforming the ways in which we create? Because it’s true! There are not that many spaces! And having a Black woman director was a first for many. Simone talked about how awesome it was for this to be the first show she did post-college. Like, if this is the world she is coming into as an artist? My god! That was not a thing I could have imagined coming out of college, even nine years ago. So that feels just as important to me, if not more. How do we tell that story? How do we make more of those spaces where folx can show up and be completely themselves? Like there were rehearsal days where [laughs] we were all in hair bonnets. That would never be a thing in a “traditional” or predominantly white space.

MSL: At this point, how do you see RWTD as continuing to develop, or do you see it as coming to a close? What else do you think you’ll bring from the experience into future projects?

QLB: Well, fortunately and unfortunately, it can’t be quite done, because I still have to write the dissertation. [both laugh] The unfortunate part is, making this play is what I was proposing to do, but I haven’t submitted the dissertation proposal yet so now I have to re-frame. I think what that means is that this is an opportunity for me to really reflect on what happened and the process, and to hopefully disseminate that in some way that’s useful to a larger theater community and educational theater community. Do we write some sort of curriculum based on this? Maybe about how communities can use the kinds of queries and processes that we used in order to investigate documents like this or to create governing manifestos for their micro-communities? Does it become a living script that’s like plug-and-play, that folx can access for their own communities? That’s where I am in figuring out what that next step is, in terms of the research.

And, you know, if someone wants to produce us to do the show in-person when we’re able to do that? We’re here! We’re ready! We would love to tour this piece and to have these conversations in-person with people, and really see what is possible in the space together.

MSL: How do you see your creative work, education work, and organizing work as being related? Have you always been involved with all? Have they grown or developed into each other over time?

QLB: Yeah, this is the hard part about my life. Like, “How is there time to do all of the things that Quenna wants to do? Oh, she just tries to make them all be the same thing.” [both laugh] Which is what I have come to. Because, at a certain point, as you know, my day job was facilitating educational theater and leading these theater programs for young people, then leaving that to go do organizing work, then leaving that to go to rehearsal to be in or direct a play. And it’s exhausting. [laughs] It takes a lot. And I think there are ways that these parts of myself can serve each other, and that these parts of our collective work can serve each other.

For the past two years I’ve been trying to figure out, how is my organizing through my theater? Maybe that’s always been true, but I’m realizing it now. I’ve always been interested in using theater as a way to investigate pressing social issues. I think that’s why I started studying applied theater, even in undergrad. Now, as an artist, I am more firmly planting myself there. In my final write-up for the Lincoln City Fellowship — through the Speranza Foundation, which helped me pay the actors for RWTD — I said, “I think the next phase is really using theater more in civic spaces.” How can theater be used to advance issues of policy? I’m thinking about that more specifically now than I was before this project.

MSL: I’m not sure if this is related, but you’ve alluded to some of the many things that have happened in 2020. As somebody who has been involved in organizing for ages — like through the Black Youth Project 100 and the #LetUsBreathe Collective — and in conversations around Black liberation and prison and police abolition long before now or RWTD, how are you feeling at the end of this year? It seems that many the issues and frameworks that you’ve been engaged in deeply for a long time are, on the one hand, getting really broad attention and possibly support? At the same time, I imagine there might be tensions and complications to that.

QLB: Yeah. In terms of how I feel at the end of 2020, certainly grateful that people’s eyes are opening, right? I just started watching this series on Hulu called Woke, with Lamorne Morris. I think it’s hilarious. [laughs]

MSL: I love that guy. I’m remembering you used to also love New Girl.

QLB: [laughs] I do, I do! I really love him. He’s great. But yeah, I think it’s complicated. Certainly, this pandemic seems to have allowed folx to be in a space where they could actually listen to what young Black people have been saying forever? And so it does feel like we’re in this moment — almost — of rupture, where perhaps folx are thinking more critically about these systems. And I think that folx will just become complacent again. They’re like, “Oh, I understand now!” And, “We’re doing all of this work about equity, justice, and diversity!” Like every organization is undergoing these antiracism trainings. And I’m helping to lead some of that work. While it is putting money in the pockets of Black folx, there’s a labor cost that comes with even thinking about these discussions. I think back to earlier in the pandemic, when my uncle called me, because I’m vocal about these things, and he said, “Hey, I have this co-worker who wants to know where she can find information.” And I’m like, “I don’t know, the internet?” [laughs] But I emailed her a packet somebody else had put together — like I wasn’t going to do that. So, you know, I’m glad that folx are engaging but it’s like, “Are you truly engaging, and what are the ways in which you are actively practicing being antiracist and interrupting systems where you are?” I fear that folx think, “Oh, if we do this antiracism training for a semester…the work will be done.” That’s just false. So I don’t want folx to get caught up in this illusion that we have “fixed” anything.

The other thing I’ll say is that I owe this entire project to prison abolition. I owe this project to Mariame Kaba, who sparked the idea. We were leaving a Movement for Black Lives convening, and for one reason or another I had just read the Declaration of Independence, and I was like, “This is hypocritical!” And she basically said, “Well, you’re an artist. Re-write it.” So I owe this project to the community of organizers and activists in Chicago.

I haven’t been as active in those spaces for the past couple of years. I did get a little re-acclimated this summer. I think I’m trying to balance and figure out, where does my activism live? How do I support those spaces and organizations that really taught me a lot, and also do these other things that I’m interested in? If I focus my energies in the theater space but continue to re-route those conversations and resources back to communities and organizing spaces — is that enough? I don’t know! I have all these lingering questions. And I think theater is a useful tool to break down some of these concepts. What might happen if we went out in parks, socially distanced, and asked people to do forum theater around defunding the police? If we just played games with folx and were like, “Hey! What would you do with $4 million a day?” That’s what the CPD budget breaks down to daily. And have people imagine and build together how they would spend those resources. I’m interested in bringing together those aspects of what I’ve learned and of my art and activism, and then asking those questions at a policy level.

MSL: Are there other projects or campaigns you’re really excited about right now? Or artists’ work you want to shout out?

QLB: Definitely the work the Black Abolitionist Network is doing in Chicago. There’s the Defund CPD campaign, and there was a lot of effort recently to get alderpeople to say “no” to the Mayor’s very anti-Black budget. Uplift and follow the people in that collective consortium of organizers.

Tanuja Devi Jagernauth is coming to mind. A lot of her work is centered in mutual aid, and she’s been doing a lot about grief lately, with Kelly Hayes and others. How are we really honoring all of these lives that we are losing? I’ll say Mariame Kaba again just because she’s dope. [laughs] Did she release an abolitionist children’s book?! Like, yes, buy that for your babies. Have those conversations. Instead of teaching our Black children to be afraid of the police. And I want to shout out Naimah Thomas, who did the poster for Re-Writing the Declaration and is doing a lot of graphic design for the movement and with folx. She’s super talented and an amazing human and if you don’t know her work, you should.

I’ve learned so much as a human and in my artistic practice through FYI. I think they engage and really center youth in a way that lots of organizations say they’re doing but don’t quite actually do. They center pleasure and center trans and non-binary folx. I’m also involved in some work with Sojourn Theatre and the Center for Performance and Civic Practice that feels very exciting and inspiring to me.

There’s just so many people, y’all! [both laugh] How can I honor and acknowledge them all?

MSL: I’m wondering if, looking back, there’s anything that you’re doing now or about who you are now that you think teenaged Quenna would be totally amazed by or that you’d love to say to her?

QLB: “Don’t be afraid. Just do it.” That would probably be the biggest thing. I spent a lot of time just, “Oh, I don’t know if this is the right thing to do….” And not being bold. I don’t know if this is because I’m in my 30s or because of this work with organizers and really being able to be myself, but just, “Be unapologetic.”

MSL: A flipside question is, looking forward, what do you dream for your own work?

QLB: One, just to be able to keep doing it. I do recognize it as a privilege, to be able to devote as much time as I do to a creative practice. And, sometimes, I feel like that’s not enough! Like I want to be doing that full-time! I guess I want to be doing more of it and to finally figure out that balance of creative practice, of education work, of organizing, where I feel tired for the right reasons and not tired all the time.

I’ve always said this, but somebody should let me and some other people into Congress to do forum theater. I think that things would look a lot different! Also maybe at some point I still am going to run for President. But it will be a complete act of theater, and I hope everybody’s ready. [both laugh]

Featured image: A headshot of Quenna Lené Barrett. The photo is a close-up of Barrett, a Black woman, that shows her face from her chin to just above her eyebrows. She looks directly at the camera, slightly smiling with a knowing expression. Her face occupies the center of the image, framed by her hair, and she wears a dark blue top. Photo by Juli Del Prete. Image courtesy of Quenna Lené Barrett.

Marya Spont-Lemus (she/her/hers) is a fiction writer, interdisciplinary artist, and informal educator, who lives and works on the Southwest Side of Chicago. Find her work on Tumblr.

![[placeholder image]](https://sixtyinchesfromcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Quenna-Lené-Barrett_Headshot.png)