“Beyond the Page” digs into the process and practice of writers and artists who work at the intersection of literary arts and other fields. In March, I was honored to interview artist and educator Carlos Matallana about the development of his ongoing Manual of Violence project, the process of creating its fictional comic installment “Brea,” and how games, childhood, dreams, and more shape his work.

Follow @tropipunk on Instagram and check out his presentation about “Brea” at the Hyde Park Art Center on Saturday, May 26, 2-4pm. This interview has been edited for length and clarity, and includes some spoilers about the book “Brea.”

Marya Spont-Lemus: I guess I’d love to start by just hearing how long you’ve been making work in Chicago and what brought you here.

Carlos Matallana: Well, I ended up in Chicago because I have old friends here in the city. But initially I moved from Bogotá to New York. I spent a couple of months, not even four months, in New York. I spent all my savings, and I tried to work, but measuring the time you need to work to live in New York, I had to take so many jobs that I couldn’t live. I was originally supposed to work with a small boutique, or ad agency. I was used to working with only the graphic design—that was fine—but then in this boutique I was supposed to talk to the client. And the jargon of design in English is different. I knew basic school English, but developing a project—more intellectual—it was tough. I just couldn’t handle it. So I decided to just work in something else, but something else was very badly paid, and I was in survival mode. Then I had family in Texas, and I went to visit them. New York was like people all over, you know, crawling out of everywhere. [both laugh] Every corner, every hole. And Dallas was empty almost. While living in Dallas, I visited Chicago, and Chicago was a perfect balance between both. So I visited some friends here and they asked me to stay, and I found a graphic design job and that was how I started working. And that’s why I’m in Chicago.

MSL: So did you study marketing or graphic design? Or was that what you were doing in Bógota that then brought you to New York?

CM: I studied classic painting.

MSL: Oh, wow!

CM: Yeah, I studied since I was…10? I started with a master, so I had to clean his brushes—like the traditional way to learn. You have to clean the brushes, then you get to maybe touch one of his paintings. Like, do the first layer. It took me a couple of years to actually paint on one of his paintings, and then he pretty much goes in to refine my strokes. So that was a process.

MSL: You started when you were 10 years old working with someone in that way?

CM: Yeah.

MSL: Is that common?

CM: It’s not. It is not. My mom always believed in education—the middle class commodity, you know, education. That was after school. So every time after school I took a bus and would go to the class. I was the youngest, I was like 10 years old, and there was somebody who was 16 years old, 18 years old, and then everyone else was, I don’t know, my parents’ age.

MSL: Wow.

CM: Yeah. It was an apprenticeship, of sorts. The guy who was older than me, Jaime Rojas, started by doing the same thing. So I was helping them both. That was how I started doing painting, and oil painting. And that lasted until I entered university.

When I was in the university, I told my painting teacher that I had apprenticed for, Roberto Rodriguez, that I was going to be doing comics. And that was a big…. He wasn’t happy. After spending all these years as an apprentice, doing color work and everything…. And he’s a classic painter, so he looks down on comics and other media, video even. It’s a very strict set of mind. Hyperrealism and all that stuff. Which is great, I learned a lot. But yeah, I told him. And that’s when I started doing comics, and I published a small zine over there. And then my goal, to get to New York, was to study film. But then it was just too crazy to live there. So I came to Chicago and then I started doing freelance gigs and did graphic design, which was my degree in Colombia when I was studying down there. And then I started just reading, and then I published some cartoons, at Contratiempo, the magazine, back in the early 2000s, when they were publishing more often.

And I always had a story about…I don’t know, I always wanted to develop a story in comic. I never had the actual subject matter.

MSL: By that you mean, you had the ambition to do something longer and that had a longer story to it but you just didn’t know quite what the story would be yet? That kind of thing?

CM: Yeah. So I guess I was always curious, and I was always reading comics. And Chicago’s pretty much the mecca in comics—there are big authors and independent authors and, you know, there are just so many people doing cool stuff. And it’s a perfect city, also, to work indoors. [laughter] Long winters. So yeah, it’s just perfect.

And then, life goes on. I painted here, I started drawings here and there, exhibitions here and there, but nothing really that moved me or motivated me enough to keep going. Until I became a parent! That’s where things started shifting gears. Life became more meaningful—not because it wasn’t meaningful before, it’s just because I was…I had it all. I had so much time that I could pretty much be going to concerts and reading comics, working here and there–

MSL: Before you had kids, you mean?

CM: Yeah. I mean, I was pretty much on a sabbatical-tenure-hiatus…something like that. [Marya laughs] It was just reading comics—which I think is learning, too. And pretty much enjoying life and enjoying myself. And then the kids came. And then you have to share not only the physical space but they have needs and everything. So it’s a great lesson—for me, specifically. That and the fact that I lost my dad, when I became a parent, so that was a very strong shift of gears, right there.

MSL: Right around the same time?

CM: Yes.

MSL: Oh, wow.

CM: Yeah, so that was a very strong shift for me. But then at the same time, my only way to exercise those—whatever feelings I was feeling—was through drawing. So I inked on paper, and I did a lot of illustrations. It was like a catharsis. And it helped me a lot. It was a hard period to learn “How I can I become a parent?” when you don’t have someone to ask, “How was that?” But then again, my mom was there. She was in the distance. I’m here by myself. All our family—our relatives—are down there in Bogotá, in Colombia. But yeah, that’s how I started savoring more life, in a sense—trying to understand it from a different perspective. That was a big shift for me. And a good…excuse. Right? To get back to work and do something that really matters, as opposed to all these years of self-indulgences. Which is great, I’m not…

MSL: Inputs are important also.

CM: Yeah! It’s just like…growth. And it was hard, but that’s how you grow. You lose things, and you gain things. And then after a while I was trying to make sense of how… I’ve experienced the most amazing things from this city. And my orientation was always, how can I offer that to my kids? Right? And how can I somehow contribute to improve that? So that’s how the questions started. How can we somehow understand violence so that we can talk about it? Or maybe tackle it. I don’t know. But that was a big thing that started back then. Or it didn’t start back then, but that was the big thing that…when you’re a parent, you’re looking toward the future—safe future. So that’s how I started growing that as a subject, not only within my life as a parent but also within my life as an artist. And how can I contribute to make it better?

MSL: As you think back on your own childhood, are there some things where you’re like, “Oh, I remember when I was a kid and this thing happened to me and how I wish an adult would have responded”? Or other ways your childhood plays into how you think about parenthood or your work?

CM: I had a very happy childhood. My parents set a high bar in that sense. And we weren’t rich. We were just middle class. But we were lucky to not be affected by the conflict in Colombia even though we had family who had. But our nuclear family, our small family, didn’t get affected directly. And my parents weren’t preachy about stuff, about anything. I remember my dad—he was a union worker—and he took me to meetings of the union. I always felt like there was this way to tell you things without telling you, like very subtly. “You belong to this.” You know? Without telling you, but inviting you and making you a part of it. And I think that was very moving for me, and was a very formative experience. So that’s one. And then also vacations. We would have vacations, where we would just go out and enjoy the countryside. We would travel around the country.

So they set that bar very high. I had a great childhood, a very happy childhood. So that was my big question: “How can I make a child happy?” To have a very similar experience. As opposed to parents that maybe didn’t get enough, and they are trying to provide whatever they didn’t have to their kids? In this case it was the opposite. They were very balanced. They were very strict, too, but I didn’t have them under my skin all the time. So how can I keep that same method? How can you keep a balance between happiness and responsibilities, too? It’s hard. That is hard. I think that was my big fear in terms of becoming a parent. Because it’s very easy to spoil someone, not only a child but other people too. I guess my parents also improvised, as I’m doing now. [laughter] So that was my big shift.

MSL: And so when did the Manual of Violence as a framing for your work come into play? Did you have a moment where all of these concerns crystallized? Were you noticing tendencies in your work that were leading to this larger umbrella? It seems that you include workshops you’ve done under it, as well as games and this book we’re going to talk about. I guess, what is the Manual of Violence to you, what is its purpose, and where does it come from?

CM: I think the shift—there’s a personal shift and an environment shift—that provoked this concern about “what’s next?” was when George W. Bush was reelected. And by then I had a very comfortable job—I worked as many hours as I wanted. So I was like, “Instead of working for this corporation, I’d rather be doing something more constructive.” Because what I noticed was a lack of education, and that ended up in the reelection of Bush—which hasn’t changed much since then, as we all know.

A friend of mine was leading a class in graphic design at Gallery 37, and she asked me if I could help her with it, to teach the students about graphic design. And I said, “Great!” So that was how I started, and then I started engaging with youth, at some point. I underestimated—because I wasn’t interacting with any young people, so I was like, “Oh these young people in the U.S. are sort of spoiled…”—but then after interacting with them, I noticed that there were a lot of things going on, when you are a teenager, a lot of changes. And everyone is trying to do their best, with the tools they have. Back then, the web was coming back, after the big crash and Y2K, so I developed a program—a curriculum—on web design. And it was the first in the city, as an after school program for teens. And they loved it. They ran it at Gallery 37 and in a couple of different high schools. And it was great. The teens developed their own content—reggaeton, hip-hop, basketball, whatever they wanted to develop. It was their own. But they had to code it. So I got more familiar with the students and kids and that generation. And that was the generation that I thought needed to be somehow prepared for the future. So that’s why my brain pretty much shifted gears from graphic design towards education.

Back then, I wasn’t a parent or anything. And then I became a parent so I tried to create…initially, it was like a guide, like a manual, “how to deal with violence.” But then after talking to different people, I realized that the “manual of violence,” the guide about how you can approach violence…it was a stance. It was my stance—as a privileged, middle-class person—telling someone who has been suffering violence all their lives, or victims of violence, “No, this is what you should do.” You know. That was the initial intention, “This is how you should deal with violence.” But I didn’t know anything about it, like I said. I had a happy childhood and I didn’t know anything about it. It’s a very, very…paternalistic approach to violence. So I got back from that approach. And when I say a privilege, I don’t mean the white privilege, I mean the middle-class privilege. The middle-class privilege that can talk about it, can philosophize about it, can actually discuss it openly—in forums and the schools and everything. There’s people who can’t even mention it. There’s people who have been suffering from it for all their lives and they don’t know how to name it, because for them it’s a way of life. You know? So that’s what I mean when I say privilege, the privilege of discussing it as a subject. So I changed my stance. I stepped back and kept reading and working on it.

And again, going back to the teens. That’s when I developed the game, “The Anger Games.” That was after the financial crisis. And people didn’t know, including me, about the financial situation…there’s not a financial culture. There’s just a spending culture, but not the knowledge or acknowledgement of how much money you can save, how much money you can spend, how you can invest. And I didn’t have that culture in my home. And here in the U.S. it’s just the credit culture. So the game, “The Anger Games,” focuses on that. So I was trying to give the teenagers—that was a high school—tools so they can explore what financial education means. By just playing with it, so they have a better understanding. And that led me to another approach of how complex things, such as finance—which is very complex—can be explained through games very easily. And that leads to power, and empowerment, and how they can challenge power by being empowered.

MSL: And is the thing with games that it enables role-playing? Or that it’s calling on people to make a decision in the moment, that is asking them apply their experience in some way? What do you think it is about games that enables somebody—or you—to engage with that complexity more than another form?

CM: In this case, the role-playing was particularly motivated. There’s a group of kids who were bankers. A group of kids who might become mayor, or they might work for the city or for their district. And at some point the players themselves can pick a random card and shift to become an older lady, like 60 years old, with no insurance and no benefits or anything—and they have to play that role. Some other times they have to—it was a giant board—marry the next person over, regardless of if that was a male or female. And they are going to marry and they are going to be living as a couple in the game. So, in that sense, they may have to try to understand what are some of the challenges to same-sex marriage, to life as a same-sex couple, around the game. So role-playing was key in that element. And in the game people get sick, people get into accidents, people have to dance. Not everything is bad. It’s a game. But there are subtle, little things that maybe help them to understand someone’s stance. Which was the main goal of the game.

MSL: A couple of months ago, I participated in a live action role-playing game for the first time, and it was a really incredible experience for a lot of reasons. One, the role that I was assigned was something completely different than who I am. In this particular LARP-ing, we each got a booklet about our character that said, “this is your age, these are some of your life experiences, here’s this thing that’s going on with your body, this is your relationship with your child.” And then everybody also had assigned goals that were specific to their character. But you don’t know each other’s goals, right? You can kind of get at some of the intentions—or begin to think you understand some of the intentions through the actions that you observe or by listening to what people are saying.

But when we finished the game, we all shared out, like “this was one of my motivations” or “I was supposed to make sure that you didn’t talk to this other person.” And then you have that moment where you’ve played through all of these scenes and maybe, by the end, you feel like you know what’s going on, and you’re acting in ways that are commensurate with your understanding of what’s going on…. [Carlos laughs] But then, at the end, you’re like, “I was kind of right about that thing, but I really misread this other thing.” So it was a really incredible exercise. I can imagine how what you’re describing could unlock those kinds of experiences for people and help them discuss them.

CM: Yeah. Yeah, and the greatest part of the game was the focus group afterwards. The kids were very critical about the game. “We need to change this, we need to change that, this needs to be improved.” And that was great! That was awesome.

So that was another learning phase. And all these different aspects of workshops and forums about violence as a subject matter, the game, the discussions in regards to institutionalized violence—pretty much they’re art, or public art projects, but at the same time they served as a research phase for the book. And that’s how I intended. Instead of developing a guide of how to handle violence, I left the name because it’s sarcasm. But the idea is pretty much to deconstruct violence and all the reasons that are linked to it and just show it as it is, or instead of pretending to show a solution I’m trying to understand it and help other people understand where urban violence comes from.

Which is not all different from the similar experiences in Paris or in London. It’s just that we are embedded here, so we only experience the here and now. There can be a very myopic perspective about it. But some of the patterns are very similar—in London, Paris, and Chicago. Like, the immigrant force. The immigrant, relegated force. Or the Great Migration here in Chicago, where African-Americans were segregated into certain areas of the city. And that’s not all different from the situations for Arabs and Africans in France, in Paris. Similar to London. So it’s a very, very compelling subject. But at the same time there are patterns that I can pick up on. And that’s what I’m working on, very much. So each of these projects builds a layer, to help me understand what’s going on in a city like Chicago.

MSL: Is what you’re saying that you’re trying to understand violence in the context of Chicago but, in so doing—in creating books or games or these other experiences—the hope is that someone could experience those and further understand or talk about something that’s happening in their context, even if they’re not the exact same things that might be happening in Chicago? Or just calling on someone to pay attention to those kinds of patterns wherever they are?

CM: Well, when I mentioned the other cities, it’s just because it’s not unique to Chicago. That’s my point. In regards to the goal, it’s to understand it. It’s for me to understand it first, but at the same time to show people how, in certain positions—like the role-playing or in the forum—how they can actually talk about violence, within a classroom. Those are effective tools to start building on how to resolve the issues. They’re just basic, elemental tools. And they’re not new. I’m not proposing anything new. I’m just trying to make them work for my project. And at the same time, while I get benefit, some more people get benefit from it, because they’re open forums or workshops in regards to the same topic.

The other part of it is I was trying to highlight profiles of people who are working in the field, like on the ground, and they are just working, that’s their everyday life. They’re not working to get any acknowledgement. They’re just working because that’s their purpose in life pretty much. So there was this boxer, Rodney Wilson, who was my first profile. He’s an amazing person and he grew up nearby and he’s been traveling around and he told his story. But he’s just humble and working with the kids in the neighborhood. And he’s trying to do his best. He’s doing it. He’s great. He has the charisma, he has the strength, other things, too. And I picked him, in particular, because boxing is apparently a violent sport, but it requires a lot of discipline and it requires a lot of commitment, too. So they’re very opposite things, in relationship to violence. And then I moved on to art teachers. I have at least ten more people that I’ve interviewed, and they’re amazing—they’re amazing experiences. I learned a lot from them. I have just published three or four, but I have plenty more. I haven’t had the time to edit all the videos. So that is that.

Carlos Matallana, “Guns Down Gloves On,” a video interview with Rodney Wilson. Courtesy of the artist.

Years ago, I ran into one of the people I had interviewed. And I don’t know what he said that somehow sparked…. But I had omitted something that he wanted to be seen in the video. And I was like, “Hmm.” And that kept bugging me, because I thought it was important. So what I did is—with this book, “Brea”—try to assemble all of the experiences of the peace builders, how they grow up in Chicago and like every little piece, try to adapt it to the story of these two kids growing up in the city. And that’s how “Brea” came to life. Because I felt like I owed more to them. To this group of people that just…

MSL: Had been helping you think through these ideas for a long time.

CM: Yeah! They’re sitting with me for over an hour each, to try to understand them, and understand their position in regards to certain topics of violence. Or education, or living here in Chicago, or whatever. So this “Brea” is more for them—as pretty much my inspiration.

And then there’s fiction. There’s, of course, two kids—you never really see an adult, which is elemental. It’s very much a Peanuts/Charlie Brown sort of thing. It’s their own universe. And the only space that the kids share with adults is the street or the school. But then at some point they realize that their school doesn’t exist anymore, that they have to change schools. That’s something that I wanted to integrate. And how they do understand those changes, and they do understand whatever’s happening, within that context. But then…there are no answers.

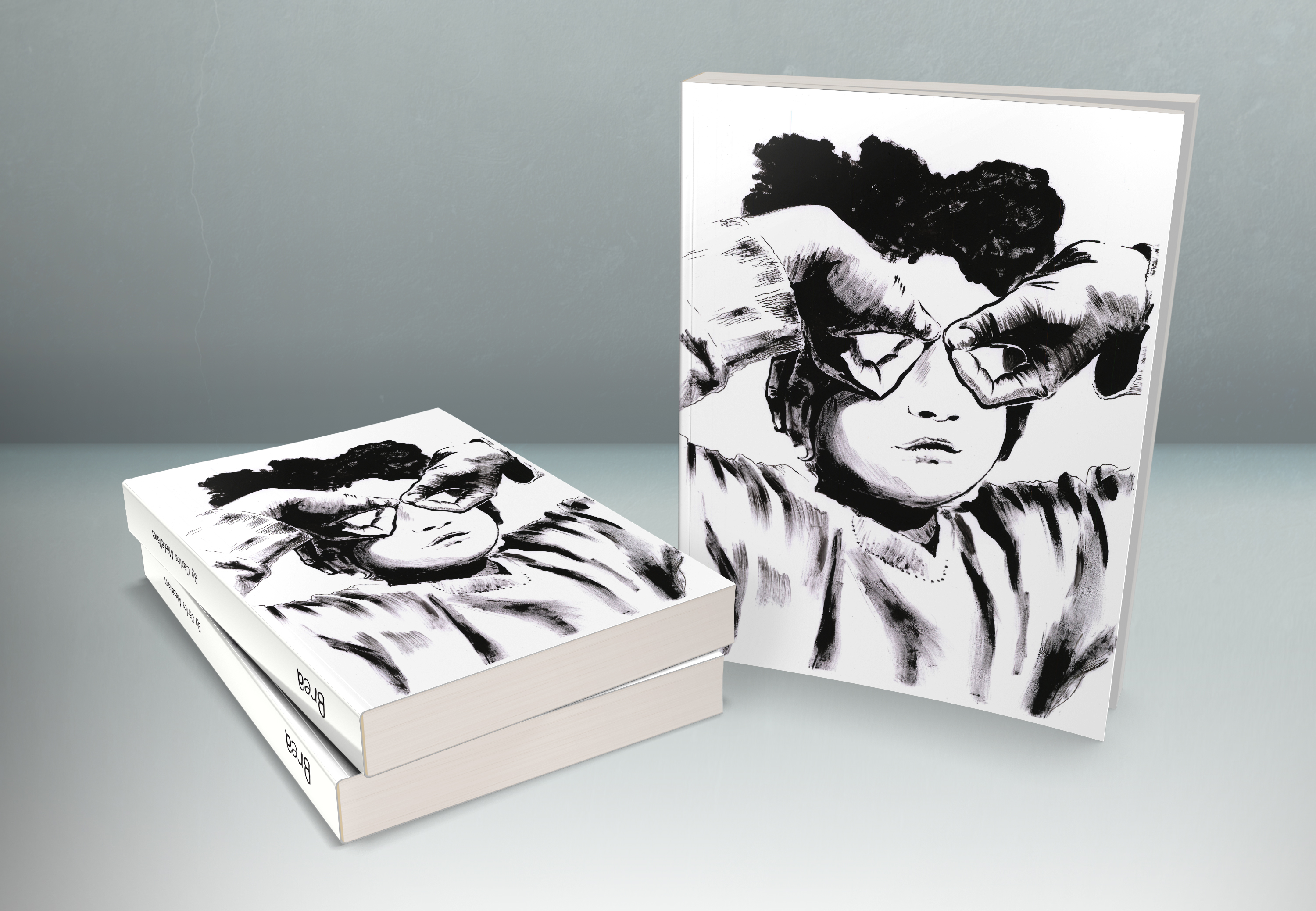

MSL: Yeah. And I’d love to shift to talk more about this book, “Brea” [Spanish for tar or pitch], which was released in the fall?

CM: Yes.

MSL: And you call it a comic book, right? And a “fiction installment.” So it’s a fictional comic book, but it incorporates a lot of non-fiction research that you’ve been doing.

CM: Yes.

MSL: How did you come up with the idea for the story that’s at the center of the book? And for some of the things you were just alluding to—like that it’s from the perspective of children, their relationship, the arc of the book as a whole, particular scenes. Whatever you want to share about how you developed from that place into this book that’s in front of us?

CM: From the beginning, I was pretty sure that I didn’t want to tell a straight story, A to B. I wanted to interlace it with dream sequences. Just because they are a very important part of my life—I write down my dreams and I keep track of them and I understand, somehow, how they affect my decisions. But at the same time, they are my own dreams. I don’t hope for anybody to understand those dynamics. But that’s the same way I’m trying to do it here. I’m trying to imagine the character’s own dreams, how they imagine their own dreams. So it’s like there’s reality, which is very stoic and cold, and then dreams, which aren’t either happy or sad, they’re usually just bizarre and awkward. So that’s the idea. I had that in mind from the beginning.

And then, hopefully, this is only the first book. I have more sketches for two more books, with the same characters, developing. So this is part of a series. As opposed to the other, non-fiction book, which is…70 percent done? And it’s like, that’s it. I don’t want to see that any more. [both laugh] You know, it’s been years of working on that. But yeah, that’s the idea. I know there are so many questions at the end of “Brea,” and they might or they might not be resolved in the next issue. But that’s the goal. That’s an exercise.

And I think I owe this to—like I said before—to these people. I just showed up from nowhere and said “I’m interested in doing this” and they were willing to take their time and talk about their experiences and growing up in the city. You know? So this is to them. And then the other, non-fiction book is more my own perspective, my own take on that.

MSL: So with “Brea,” there are two main characters, a boy and a girl, and the boy has this project or inquiry that he does throughout the book, which is this kind of map-making. And he’s very clear—it’s not “drawing,” he’s “map-making”—which I thought was great. Could you talk about what role map-making plays for this character, and why that is the mode of inquiry? And how does that thread through the narrative as well?

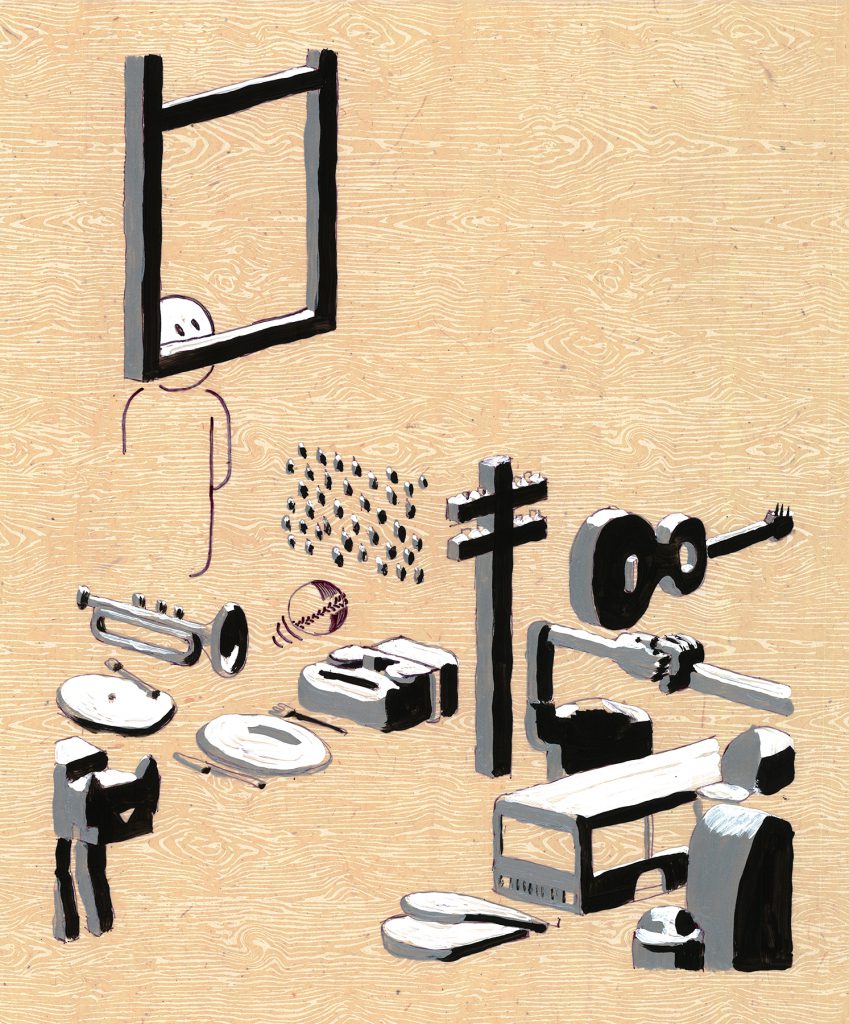

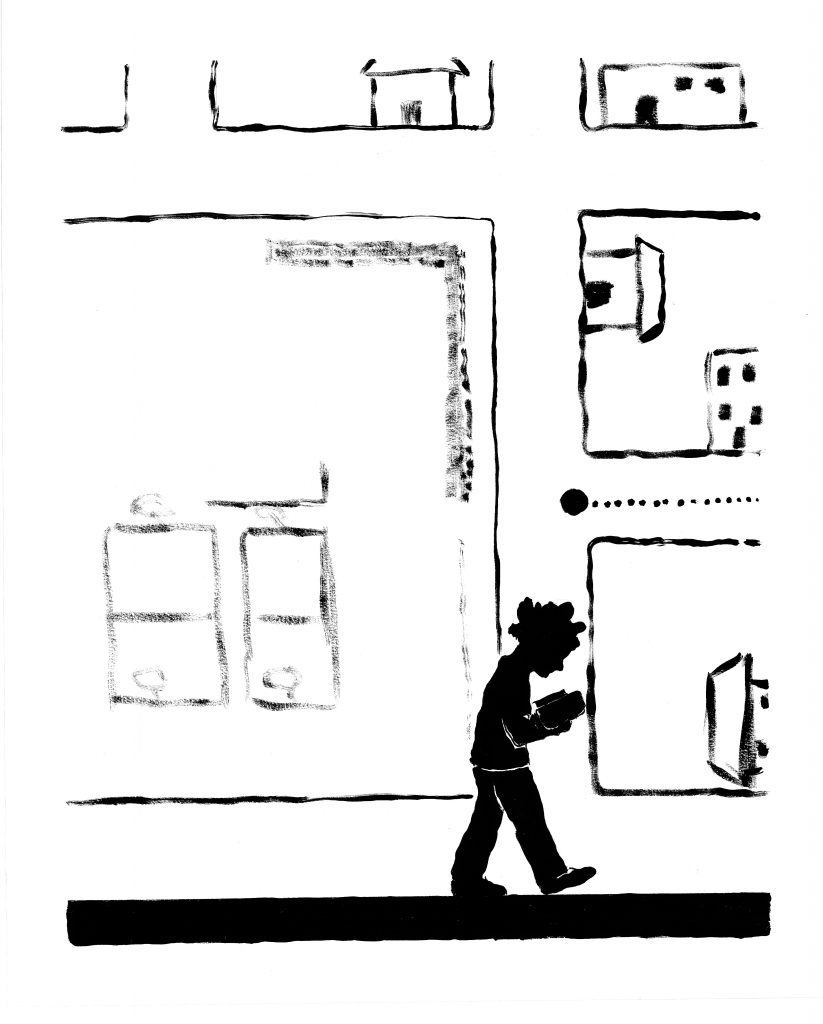

CM: I didn’t come to this conclusion until I heard it from people I interviewed here—like Brenda Hernandez, and Brother Mike Hawkins, and Rodney Wilson—but they mentioned mapping. Like, “Okay, so I have to avoid this corner.” “I have to….” And I used to do it, as a city kid. But mine was to avoid dogs, angry dogs. I once saw a cartoon, from Matt Groening, who had a map like that published, which reminded me of my childhood because I was trying to avoid angry dogs around the neighborhood. We, somehow, sense danger. So we pretty much create a navigation system. Just like, the fact of going from school to our place, especially if we have to walk alone. “This is safer,” or “this has more light,” or “this has wider sidewalks,” or who knows. I think that’s an element that’s always there in city kids. I mean, I guess the same happens to countryside kids—because I spent a lot of time there—how you can get from A to B in a shorter distance, but at the same time having adventures and avoiding maybe water or angry dogs or something. I don’t know. So I think that’s a navigation system we sort of develop and then we have it. The specific elements added there are for the story and the navigation system will grow with that.

MSL: Yeah. And it was really interesting to see that from this character’s perspective because there seems to be a way that the main character becomes more aware, in a way, over the course of the story. It almost seems like he observes these things—like people’s patterns and their brea, which follows them or holds them down—before he has a name for them? And before he has that experience himself. Like he’s collecting these observations that he hasn’t quite synthesized into what’s happening around him. But he sees something.

CM: Yes. Yeah. And that’s the other element—the mystical element of it—that I guess I’m sensitive to. We’re always lured by the mystical elements of nature, but we forget the mystical elements of the city. And they are so important, too. Because the mystical is…it is attached to humans. So that’s another layer that I wanted to add there, because I know and I’m very aware of the mystical. I know there’s something out there and I don’t have a name for it—the closest I can get to is nature—but there’s something there that, somehow, moves us all. And yes, that’s there in “Brea.” And I wanted to have it be subtle. It can be resolved later, or can be explored later in the same series. It’s also in the dreams. This urban, mystical element.

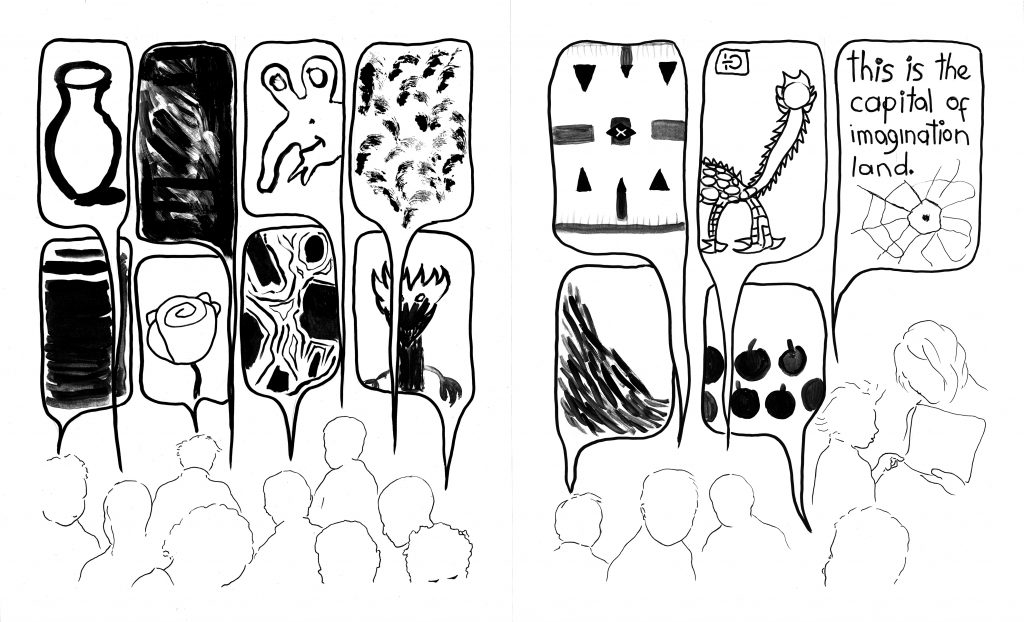

MSL: I guess I would say, too, that one of the things I really appreciated about this book was its…embrace of abstraction? It was almost elliptical storytelling, meaning that there were notable ellipses. And with the visual language—there seemed to be two dominant approaches that alternated to some extent, one of them being what you described as the dreamlike spaces. But even in the more quote-unquote “real life” spaces, many if not all of those images seemed to suggest double-reads, or at least double-reads. Part of it, I think, is the way that you drew and framed them. The illustrations are very select and sometimes sparse and ambiguous. And, as a reader, I felt like there was a space created for me—much how abstraction can engage us in a way that sometimes realism can’t, because it allows space for that movement, that is part of that process of interpretation or something.

And it was so interesting to hear you talk earlier about the origins of the Manual of Violence and your reflections on that as, initially, a sort of prescriptive or paternalistic approach. Because this to me seemed to be really open, sort of like an offering or invitation to step in and explore…to navigate it yourself.

CM: Yeah. Yes. One of these elements that is very open is the school. The school is not portrayed as something very good or something very bad. It’s just a school. But then those memories of the school are complemented by the experiences of the people who read it, who scan the pages. And like you were saying, I want to leave a lot of space for that to be filled in, by the reader. As opposed to telling them what to feel. Like, “How can you understand this situation or this character?”

And then, also, the wandering of the streets. Which is, for me, a very amazing thing that I was able to do. And I think it’s one thing that we lost. I think it’s one thing that we need to engage or we need to improve. Like so kids can actually go to the street and just enjoy a walk, where they’re wondering about whatever. And they may be doing it. I’m suggesting it just as a way of moving, not because they lack something, but because you see them enjoying it when you see it, and wondering about their environments. Like about Amanda Williams’ pink house [Pink Oil Moisturizer from Color(ed) Theory Suite], which I heard from other kids. I was like, “This is great.”

MSL: Meaning that kids told you about it and then you went and looked at it? Or you had a sense of it and–?

CM: No, I was walking by—I don’t think it was the pink house, I think it was another house; I’ve seen a couple of her houses—and there were a couple of kids that were just talking randomly about it. And it was similar questions to those the characters ask in the book when they pass the pink house. And it’s not like they don’t get it, it’s the fact that they question about it—I think that’s one of Amanda’s goals—about this space, how they gain space, how they can start questioning space in a different way. And I think that’s great. And, of course, there’s wonder in her work, which I deeply admire.

But then space—going back to space—there’s this movement, the Situationists, in France. And it goes back to the same thing. How do you enjoy and embrace space? How is your place in the city? And how do you take advantage of it? So that’s one reason why I made the characters walk, I made them be wandering around everywhere. And I did some scouting and I used some references—so there are some streets that would seem familiar if you’re from the South Side or some spots. When I see kids walking, I just love that. I think it is great! Like a healthy environment. Right? Where you see kids walking and saying, “Look.” Carelessly. Just walking. Enjoying life. Looking for where to have an ice cream. Or going to the library or just going to the school. So I think that’s one thing that I insist—deeply—on. It’s very evident, of course.

MSL: How did you come to tell the story from a child’s point of view, and how did it feel to do that—to write as a child, as an adult?

CM: Oh, these two. They are the guilty ones of–

MSL: Your kids.

CM: Yeah. Samuel and Marcela. Because they’re always very, very inquisitive, in what they see me doing or in whatever conversation we have—with Natalia, my wife. So that’s one. I love whenever they are in the backseat and we listen to them talking about random stuff, how bizarre that gets? [Marya laughs] Like the levels of abstract conversation. We understand them because we hear the conversations from the beginning, but if someone got into that late in the conversation they would be like, “What? What’s going on?” Right? And it’s not far from a very philosophical or very academic jargonized conversation between two scientists or two philosophers—it’s no different. Because it’s just very, very abstract and very, very bizarre. And, for the same reason, that’s why I decided to have similar ages in the characters. But they live in a separate world from us, a different generation, and we as adults don’t know about that. And they drew the typography, the typeface.

MSL: Your own children did?

CM: Yes.

MSL: I was wondering if that’s what that note at the end meant.

CM: Yes. [points in book] So Marcela illustrated the girl’s. And this is his…

MSL: Did they individually hand-write each of these parts, or they wrote out A through Z and then you turned them into fonts?

CM: I turned them into fonts.

MSL: That’s amazing.

CM: Yeah. So I’d give them a template and they just did it. You can see the difference. Oh, and the kids modeled. [points to the front cover] Samuel modeled for this, [points to the back cover] Marcela modeled for that.

MSL: I was going to say! “These kids look a little familiar to me, I wonder if they’re supposed to be–”

CM: Not for all of them—because they don’t have the patience. [Marya laughs]

MSL: So the font, your kids literally created, and they modeled for a few illustrations. The inquisitiveness of the two main characters is loosely modeled off your children’s inquisitiveness—or those kinds of conversations. And you’ve obviously done all this research, so you’re synthesizing other people’s stories and some of the experiences of working with young people yourself. Were there points when making the book where, maybe once you had a draft, you had your children look at and be, like, kid consultants for it? Or that you brought back to people you had worked with earlier and said, “Here’s where I’m at”? How did that part of the process work?

CM: Yeah. Well, it wasn’t with them, specifically, but with Bea Malsky. She’s the editor. And it’s funny, because we were talking about non-fiction and I was giving her drafts of my non-fiction, and then I said, “I’ve got this one, it’s ready, so we have to publish this one.” And she said, “Okay, let me see.” And I passed her this draft and she was like, “Why are there these two kids? Why did you decide to change the thing to two kids?” Then she understood that this is a fiction installment. I mean, it has a lot of relationship with the non-fiction, but this is a different project, a different persona, a different take.

MSL: Was she an independent editor who you hired to work with you on this project? Or she was somebody who–?

CM: I’ve worked with her before.

MSL: For comics specifically?

CM: Yeah. She has followed the project from the very beginning, since the first forum discussion about violence as a subject matter that I did with teacher artists. She wrote an article for the South Side Weekly about the project. And she’s very talented and she has this very—how should I say it?—dry honesty? Which I really admire.

MSL: Mmm. Good quality in an editor, I hear. Yeah.

CM: Yeah. She’s just great. And she doesn’t mind telling me not to do things because they’re redundant or anything. So there’s excellent communication and she’s amazing. Not just because of this but because she’s done a lot more work in relationship with comics. She’s a great talent. So we went back and forth, we double-checked, we met, we interchanged final proofs, she adjusted some of the text, and then we reviewed some of them together before it was final. And my big concern was, I didn’t want “Brea” to sound preachy at all. Because that’s very risky. And she read it and said it didn’t, and I trust her. And I read it and she’s right. It doesn’t sound like that.

MSL: Yeah, it didn’t read to me as preachy either. I wonder how much taking the child’s point of view helped? Adults weren’t invisible in the story, but we see what the main character sees. And there are parts where the children saw something happening that adults didn’t see or fully understand. Early on, the boy says that teachers thought something was a shadow but he knew it was something else—and it’s before he knows what it is exactly, but he does know it’s something else. Or when the door won’t close, and the teacher says it’s because of heat and the wood frame and the boy thinks to himself, basically, “no, it’s because the brea’s blocking the door.” Those kinds of moments. Something I was thinking about a little while reading was a panel discussion I saw a while ago on YouTube, with Junot Díaz and Karen Russell, in which they talk about writing children [41:20]. And Junot Díaz says, “children haven’t built up their amnesia.”

CM: Yes.

MSL: And I think he particularly mentions racism and sexism, among other things. But there’s this way that, in writing as a child—I mean, in writing as anybody you can do this—but in children there’s a very real, like, “No, I see this thing, you can deny that it is happening, but because you deny it’s happening does not mean it’s not happening!” So there’s this real beauty to that, a clear-eyed view of injustice that one can further unlock sometimes in writing as a child.

CM: Yeah. Yeah, I agree with that. I guess, going back to my childhood, I saw unjust things on TV or in the streets and I asked myself, “Oh my god, how can people not see that this is happening?” Then I’m like, “Nobody told me anything. Okay, it happened. Maybe they didn’t notice that I saw it happening.” You know, things like that. So yes. That’s true.

MSL: I also thought it was interesting that adults, in other ways, became more visible in the book towards the end. On the one hand, it seemed like the children were overtly crediting—at least partially crediting—their teachers with awakening their curiosity, in a way that didn’t make the brea completely go away, but it became spottier. So something about the teachers’ engagement with their curiosity helped…not quite helped heal them but helped them engage in something else.

CM: Yeah.

MSL: But then also there’s, within a couple pages of that, what did feel like a more overt critique of adults to me, which comes around when they read the newspaper article, right? And I thought that was an interesting choice too. Earlier on in the book, there’s this traumatic incident for the boy, which shows what I think a lot of people and media talk about when they talk about violence. But then at the end, we see this other kind, where the kids are talking about the “legislative gun” and school closure as a form of violence. And I thought that was an important inclusion as well, that really seemed to be pointing something back at adults reading.

CM: Yes. That’s intentional. Like institutionalized violence, you know? And without being repetitive—to just say it once. That’s more effective. And that’s the whole idea of it, and also how they take it. Like, they know about it.

MSL: Children do.

CM: Yeah. And in this instance, with these characters, they know about it, but then there’s nothing to do, because they don’t have the tools to fight the legal machine, right? And that’s how things are designed. Once you have the lawyers or whoever knows how to play the game, that’s what matters. And that’s the saddest thing. And that’s one of the things that I wanted to point out there.

I think we have to come as a city—not as a North-sider or as a South-sider or as a West-sider—but as a city to try to resolve those elements, those issues. As a whole. In order to make things work.

MSL: How did the process of making this book, “Brea,” change you? As a general question, but also specifically do you feel like you gained any insights through the process into things that you think maybe need to happen or could happen? Or did it raise more questions?

CM: Hmm. Yeah. I think it resolved some personal questions, but the idea is to open more questions for people. Like you were saying: with the legal, the brea, the mystical part of the urban… So that’s the idea. And I believe I accomplished that goal. But then again, this is just one element. One thing that I am sure of is that I need to keep working in order to produce more work. Somehow, to keep the story going and share people’s perspectives, people’s often unheard perspective, and their take on everything—not just on the bad things, because that’s pretty much victimizing people that I don’t have the right to. How are they actually enjoying every moment, too? As we all do, we’re trying to do our best. So that’s the goal, try to just keep working. Once “Brea” was finished, and I saw other people’s excitement with it, that propelled me to work more, on more things.

And that’s why, pretty much, I instigated the podcast project—Blok by Blok—to give kids more tools to speak more often and louder, so we can hear their perspectives. And it’s a process and it might be a long process, but I just keep pushing. You know. That’s why.

MSL: You just touched on something I loved about the kids’ relationship in the book. As we talked about, there’s a scene that happens early on, which deeply impacts the narrator, and we learn later that his friend has had a traumatic experience too. But they also go to school and for walks in the park. And in one scene the main character might comfort his friend when she’s breaking down, and in the next he’s chasing her with fake goose poop. [both laugh] Right? There’s this aspect of play and childhood that can look a lot of different ways, but that co-exists and continues with the characters through other experiences. And I thought that was not only done very well in the book, but was an important reminder that, you know, every person is a rich and complicated human being. Children as well as adults.

CM: Yeah. Thank you. And I think that’s one of the things that we learn from kids, is how they shift as a way to move on, right? From something very traumatic to humor, or do something very silly in order to avoid doing homework. You know? That’s a tool. That silliness. That’s a resource. And it’s very accessible. And it might sound cliché, but that’s one thing we adults always forget, how to be silly. When you grow up you feel like you have to be this way. But then silliness is amazing. “Whoa!” It’s a relief. [laughs] So yeah. That’s one of the things.

And then just seeing my kids interact with other kids led me to random scenes in the book. You see some scenes that are like, “What is happening here?” Just randomness. But then again, they’re very familiar to a school or to a parent or to someone who went to school. They’re awkward and tricky. One thing I remember—that’s in the book—is these girls who were pretending to break in a door with a code, and they were sneaking and trying to– Did you see that image?

MSL: Yeah, yeah.

CM: So it’s like that. It was in my kids’ school. And they were just having fun, they weren’t trying to…. Because it’s an open space, and the door is there, and there’s kids playing all around. But they were imagining they were on a secret mission. “Psst psst psst psst. Psst psst psst psst.” It was so weird! But they were in their own bubble. So I just sat there. And that’s the exercise I did, not only with them but with other kids we know. Just sit there and immerse in their realities. And it’s just in a snap and they’re like, “Vhwoom!” And they just pull someone in. And just with a word, they understand there’s this whole new world. Right? And it’s just like, wow, this is amazing. So yeah. That’s one of the things. Kids. Kids-inspired. [laughs]

Featured image: This is a photograph of three copies of the book “Brea,” against a light background. Two lie flat in the left side of the frame, front cover and spine visible, and the third is upright, with only the front cover showing. The front cover image is an ink illustration of a young boy in close-up, straight-on, showing his face, chest, and parts of his arms. He wears a long-sleeved shirt and his hands are flipped upside-down over his eyes to form goggles, of sorts, with each thumb and forefinger. Courtesy of the artist.

Marya Spont-Lemus (she/her/hers/Ms.) is a fiction writer, interdisciplinary artist, and educator focused on teen creative, leadership, and professional development. She lives and works on the Southwest Side of Chicago. Follow her on Twitter and Tumblr.

![[placeholder image]](https://sixtyinchesfromcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Quenna-Lené-Barrett_Headshot-300x99.png)