Art is affecting and hope-filled, expressing all the things words cannot. Cultural objects and experiences hold the power to reveal what is hidden about the world and ourselves, and artists act as conduits to these truths. While their ability to translate knowledge through visual and temporal experiences is remarkable, let us not forget that at its core, art is a technical skill that requires practice and study like anything else.

Creating community and generating dialogue through art is the ultimate human negotiation, a relational push-pull and give-get, so I spend a lot of time speaking with artist and visiting their studios to learn what factors inform their practice and production. Recently, I met with Nate Young (who also is an Assistant Professor of Studio Arts at UIC) at Monique Meloche where his second solo exhibition with the gallery, “Cleromancy” is on view through November 4.

Lee Ann Norman: The photo of your great grandfather seems to be the root of the work in this show. How did you find out about it?

Nate Young: That photograph is one that I saw years and years ago, and that memory has remained with me – even before I decided I would make art work about it. Three or four years ago, I decided this [history] was something I wanted to explore, but what really intrigued me was the idea that he disappeared.

LAN: Your family came up from the South, like many of our families. Where did your people come from?

NY: Well, that’s the thing: because my great grandfather left under duress, it’s unclear where exactly he came from. When my grandmother told me the story, she thought that he was from somewhere in North Carolina or Virginia. What I was most drawn to—about him, the story, the photograph—was that there is a blank space, a non-identity, between him being in the South and Ardmore, a town outside of Philadelphia where he ended up. I wanted to think about what exists in that absence…what could potentially be projected in that empty space. I think a lot about the frameworks ideas rest on, or spaces where ideologies are projected. Sometimes I talk about them as containers. I think of his identity as a container.

LAN: This image of your great grandfather posing with a horse opened a set of questions for you, causing you to keep returning to the image. As you’ve researched more about your family’s history, what have you learned?

NY: It’s really personal work, and I don’t want it to end at the information that I found. It’s not about me telling a story, and you now knowing something about me. I’d like to think this is about what we can all learn when we examine systems of belief. But I haven’t been able to retrieve the [physical] photograph. When my grandmother died, the relationship between my dad and his sister who lived with my grandmother was tenuous.

There’s a story that my grandfather and father tell: My great grandfather was arrested in the South and taken to jail along with the other black men he was with. The jailer happens to see his Mason ring, and when he sees it, he sneaks him out of the prison and sets him free. The other men who were with him were lynched. If it weren’t for this ring, my family wouldn’t exist. My older brother found the Mason ring [at my grandmother’s house], but after he found it, he lost it. In another exhibition, I reimagined the ring and cast one as a sculpture. I learned about the horse [in the photograph] through a series of journal writings that belonged to my great grandfather. When I originally encountered the photograph, I knew some of this history – the story about the mason ring, for example – but I didn’t know about the horse. This has been a constant process of discovery, a difficult thing to talk about. There’s a lot that I don’t want to say.

LAN: Your inclination to want to find something universal in this personal history is resonant, given the history of black people in the US. The experience of migration is something that we share culturally—the terror we were fleeing, the ways we were living. These stories are specific and personal to your family, yes, but many of us can relate and even share similar stories.

NY: Yes, which gives me a lot of reservations with this work. I don’t know if I want to tell people really personal details about our family in such a public way. And there are things I remember, but sometimes I distrust my own memory.

LAN: Your memories are also informed by your family and the stories they share with you. As you’re looking at these objects, the fragments of objects, I think it’s inevitable that the empty spaces you are trying to fill are informed by the voice of your grandmother and your father.

NY: I like what you said about forgetting in order to remember, that forgetting is a necessary function of memory because that’s how our brains work, but it gets complicated. I hope all of those complications are apparent in the work – the text, the material, and the forms.

LAN: Are the texts you use from the journals?

NY: No. These are my interpretations of them. When I was making the works, I wanted to use a couple of different voices to tell the story of my great grandfather. I’m also trying to remember certain details about how I came to this story. It’s all written from my perspective though.

LAN: I’m a writer, and I love stories, obviously, but I think of writing as a really different way of manifesting ideas to make sense of the world compared to you, a sculptor who manifests ideas physically through your hands. I’m curious about how text comes into play in this very physical, tangible work.

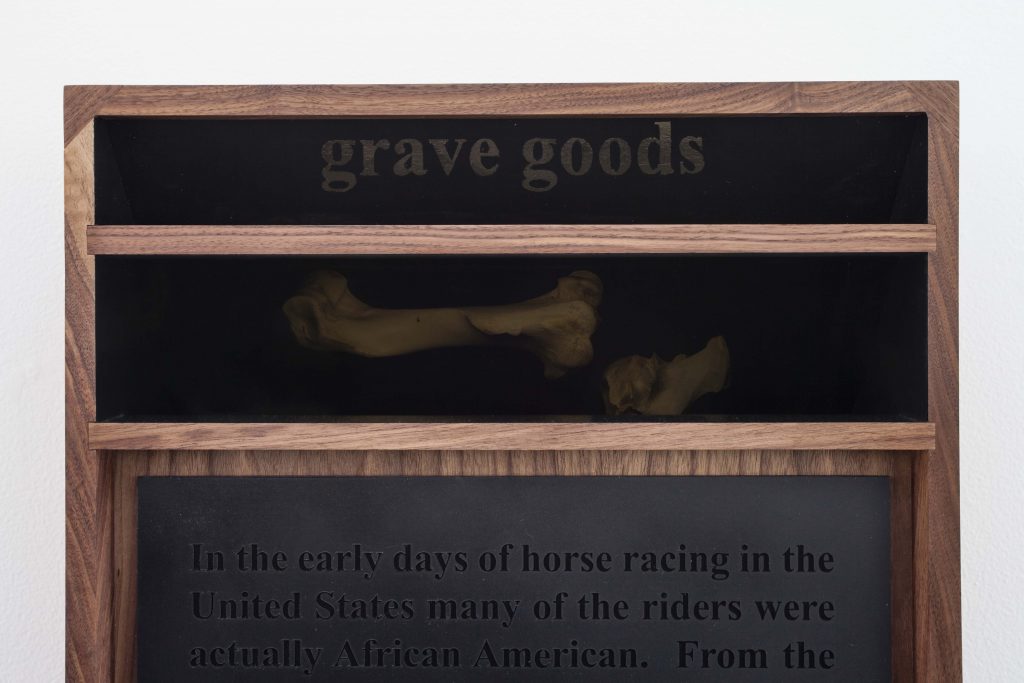

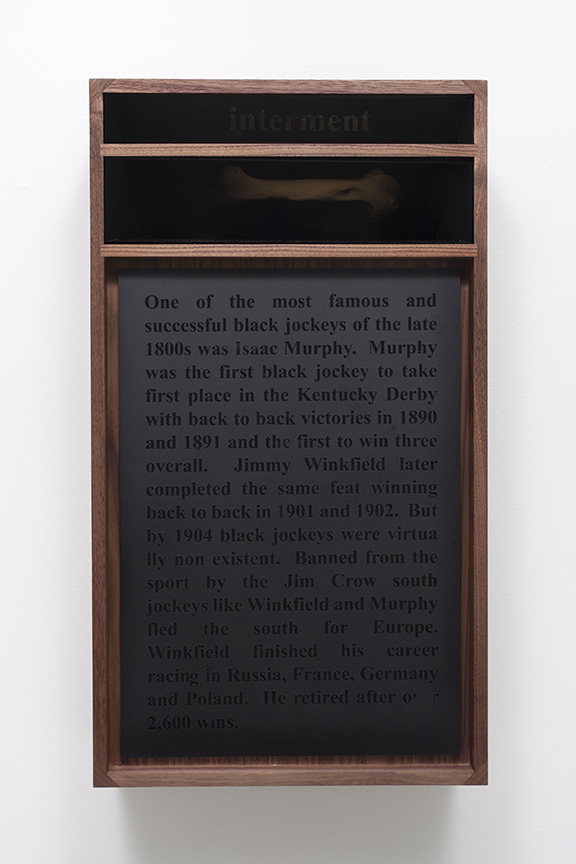

NY: Text is something that often comes into play for me. The body of work I was making before this one had no text, but included textual references like diagrams. I removed the text to think about how the diagram functions like a text and refers to ideas that are not present. The text in the drawings and [sculptural] pieces in this show is from a longer piece I wrote about black jockeys, my memories of my grandmother, a story about my great grandfather, and some history on the Great Migration. I’ve been using it as performance to give more context to this new work. (This is the second iteration of this body of work. I first showed it in Virginia without any text – just objects that referred to the stories and an installation that referred to the idea of memory.)

LAN: You’ve studied semiotics a bit, which made me I think about the number of artists who work with text – text as image or object, image as text, that sort of thing. Texts function to illuminate or explain, but the way you have used them here adds another layer to that function.

NY: It’s a text that must be experienced. In the lightboxes (I call them hologram projections) the text is about deciphering, but the material I used for them makes that difficult to do.

LAN: Right. When you look at them from one angle, the words seem straightforward, but then depending on the way they are lighted, if it’s cloudy out, how much sun comes in through the window, the text becomes something else.

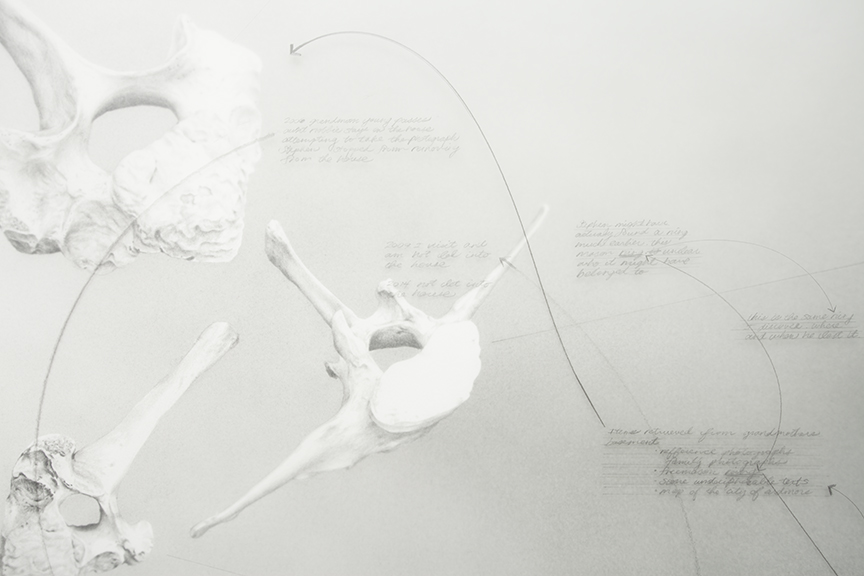

NY: For me, these are about the black on black. One is a flat black and the other is gloss. [Your experience in actual time] affects the way you see [the text] or not see, depending on what’s in the room—even people. Your body is a part of the viewing experience. Even in [the drawings], there is a suggestion on how to read the text, but it doesn’t quite fulfill its promise. If the diagram is a suggestion of logic for interpreting a text, it doesn’t quite work here. It makes sense aesthetically, but textually, an other kind of logic would have to be applied in order to keep that cohesiveness.

LAN: Yes, the arrows point you in a direction of what text to read and when, over a drawing of the bones. When I lean in closer to read it, though, there is a dissonance, and I question how the text relates to the image.

NY: And I was hoping to achieve that feeling when you step back from the image. At a certain point, the text is not legible – it’s small and hard to read – but they seem to serve as an explanation of the relationship between the bones, visually. Someone likened it to anatomy drawings in books, how they are revealed in layers. Once you read the text, it doesn’t quite land, but takes you somewhere else. You can have different experiences of the work based on your physical proximity. These drawings are titled “Divining,” which is related to the title of the show, “Cleromancy,” or the act of casting lots to receive divine knowledge from God. Sometimes small objects, like bones, are used in that kind of divination. I wanted to represent the bones in a space where they are falling, have landed, or are in the process of landing – suspended in space, and this [diagrammatic text] outlines the act of divining, although nothing spiritual is understood through that act.

LAN: So do you think of cleromancy as the container for memory, these specific memories, or a kind of collective or cultural memory?

NY: I’m not sure anyone gets to this just by looking at the work, but would hope that one could consider it that way, yes. I’d like to think of cleromancy as the framework through which believability is produced through prophecy. So, you wouldn’t believe me, but you will believe the bones, you know what I mean? They are the authoritative object. If I can think of cleromancy as the container or empty space that I am filling with these things – objects, text, memory – in my mind at least, that is parallel to my great grandfather’s absence of identity, this empty space [in his life]. Because the history is lost, I can say whatever I want about him, and no one can argue with that (laughter). His lost history becomes like that authoritative space from which I can now speak.

This is the hardest work I’ve ever shown because of the emotional labor that has gone into it. My earlier work was personal, too, because it was explicitly about my father, but I was able to strip the personal away and make it very rigid. But here, it feels really naked.

LAN: Some artists use their art making to work through things, with friends or family, for example. This gesture can make the work feel very personal because there is a care required with putting relationships with other people on display. And even though the earlier work might have felt rigid for you, I’m sure you also experienced this feeling – like you wanted to hold them, or care for and protect this work – your relationship to it and the people involved – a little bit.

NY: Yes, I think in that work, I held onto a lot of the [emotional] labor because it doesn’t say anything about me, death, my family so explicitly.

LAN: Adding the text and even the bones is a very risky gesture. I say this a lot, but I believe as creatives, we have a set of aesthetic or philosophical concerns that we return to, but try to manifest differently each time. Not that anything or this work ever needs to, but do you feel like this is resolved for you? Like: You’ve explored this, made a body of work from it, and now you can let it rest.

NY: Maybe the next step is taking a step back, letting the objects be a little more opaque. For this show, I felt it was important to put everything out there. As for resolution, I don’t know. I feel confident in the resolve of this body of work by itself, but there’s more. It’s not like the story ends, and we move on. Sometimes it takes me a long time to figure out what to do, and there are more notebooks and journals for me to go through. One morning when I wake up with a good idea, I will try to execute it, but there is so much that happens in between.

Lee Ann Norman is a writer and culture maker who works between Chicago and New York City.

Lee Ann Norman is a writer and culture maker who works between Chicago and New York City.