There is a story that begins in 1976 in New York City, at the Studio Museum in Harlem, when two young photographers met and immediately recognized in one another a like-minded artist and companion. This meeting of two young artists, both 23 at the time, was the result of the convergence of social forces, cultural movements, and a bit of fate. Their instant kinship was based upon a shared intellectual curiosity and a commitment to the potential of the photographic medium — yet these traits were a legacy of the Kamoinge Workshop, situated in the zeitgeist of Black representation of that moment and the alluring verve of life in Harlem for these young ambitious Black photographers. Since this meeting nearly 50 years ago, these two artists, Dawoud Bey and Carrie Mae Weems, have maintained a close friendship — one that has shaped and fortified their identities just as much as their perspective of the world that they explore through their cameras.

There is a magnetic force to these kinds of stories because they satisfy a desire to learn about the context that exists beyond the artwork. These tales of friendships and affiliations create a subversive dimension of art history, and they are also a testament to the adamant question from political activist and organizer Ella Baker: “Now, who are your people?” Whether amongst grassroots organizers or within an artistic cohort, this inquiry is a valid one, because our identities are not forged in solitude but in community with others. The exhibition Dawoud Bey & Carrie Mae Weems: In Dialogue offers this as a framework; a mutual regard and a shared set of values rendered visible.

The Grand Rapids Art Museum (GRAM) took on the monumental endeavor to mount what is essentially two solo, career-spanning exhibitions by two of the most formidable photo-based artists working today: Dawoud Bey and Carrie Mae Weems. The exhibition includes over 120 photographs, as well as video works by both Bey and Weems, expertly interwoven and installed, to not only provide a comprehensive view of each of their careers, but to also reveal the similar subjects that each of them have been exploring for the last few decades. Thus, this exhibition is a tribute to the rigorous practice of two luminaries in the field of photography, and also an examination of the formation of that rigor, put in context.

In the case of friendships amongst visual artists, common themes and aesthetics are likely to emerge, and Dawoud Bey and Carrie Mae Weems have developed a photographic approach that is indeed remarkably similar, both in content and style. These commonalities allowed GRAM chief curator Ron Platt to organize this exhibition thematically, simultaneously tracing their friendship, artistic paths, and dedication to the themes of race, representation, and power.

The first of the five thematic pairings is “Early Work” from the 70s and 80s: for Bey, this includes work from his Harlem, U.S.A. project, as well as other 35mm camera work; for Weems, this includes photographs and writings from Family Pictures and Stories. These black-and-white works are evidence of young photographers exploring their environments while finding their voices. Many of the photographs in this portion of the exhibition had never been displayed before, offering a rare glimpse into the formation of Bey and Weems’ visual vernacular. The influence of Roy DeCarava and other photographers from the Kamoinge Workshop is unmistakable, seen in Weems’ unvarnished photographs of her family life, or in the particular attention to light and shadow that moves across the city scenes in Bey’s photos from New York, Cuba, and Mexico.

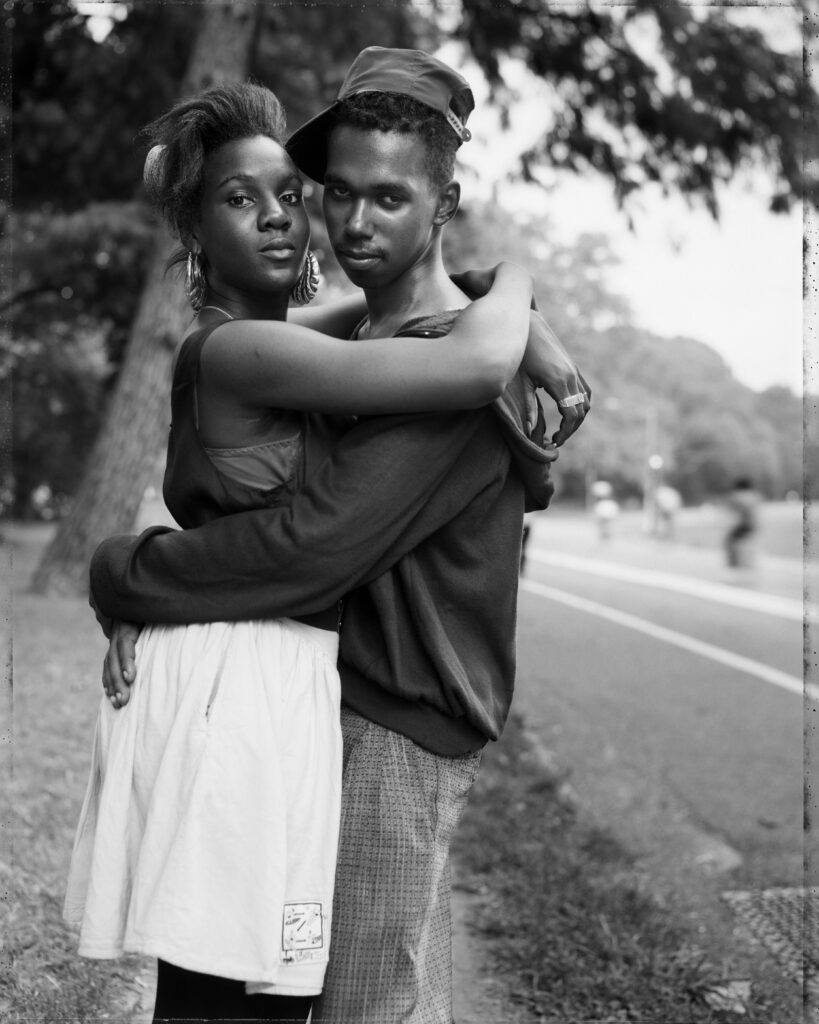

“Broadening the Scope,” the second thematic pairing, presents the pivotal work that established the careers of both photographers. In the late 80s and into the 90s, both Bey and Weems became more intentional and focused in their approach to portraiture. Bey moved to using large format cameras, which imbued a ceremonial process to his black-and-white Street Portraits, made with Polaroid’s defunct positive-negative Type 55 film. This body of work, also exquisitely presented in a recent monograph published by Mack Books, demonstrates Bey’s superpower: crafting portraits of everyday Black Americans that are arresting in their sensitivity and technical mastery.

Also featured in this section is Weems’ The Kitchen Table Series, her fictional photo essay that explores the relationships and the interior life of a woman, portrayed by herself. The typology format of this photo series — the compositions are nearly identical, with the subjects always seated at a kitchen table — is one of the reasons that this work has become instantly recognizable, an iconic exploration of Black womanhood. The Kitchen Table Series has been widely circulated, published, and referenced, but this particular installation is still revelatory. This exhibition includes twenty 40″x40″ gelatin silver prints from this series, as well as thirteen text panels of Weems’ creative writing that adds even more complexity to the protagonist in the photographs.

In both of these signature bodies of work, the artists are conjuring a performance for the camera: in The Kitchen Table Series, Weems is directing her own performance, as well as those whom she has enlisted to portray characters in this narrative; for Bey, he is deftly and perhaps disarmingly conjuring his subjects to perform a version of themselves for the camera, with specific direction to direct their gaze not just to the lens, but beyond it — to the viewer who will one day see their portrait on a gallery wall. The role of the viewer is perhaps the most significant difference in these works. The viewer is peering into scenes of domestic life in Weems’ series, which are staged but nonetheless the camera is not acknowledged. Yet the gaze in Bey’s photographs is undeniable, directly addressing the viewer with not only their eyes, but every ounce of their body language and presence.

The third thematic pairing in the exhibition, “Resurrecting Black Histories,” contains work that demonstrates a significant progression in maturity and subject matter for both artists. In Night Coming Tenderly, Black, Bey photographed landscapes and sites that are believed to be along the Underground Railroad. With careful consideration to perspective, as well as a printing technique that evokes dusk, these photographs reimagine the movement of enslaved people along this historic route to freedom. Two series of work by Weems are represented, also tracing sites of Black history and diaspora: the Sea Island Series, black-and-white photographs and text pieces that explore the Gullah culture of the islands off of the Georgia and Carolina coasts; and From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried, a rebuke of the atrocities of slavery through a reinterpretation of historic photographs of enslaved people with text-engraved glass overlays.

This particular section of works, specifically the quartet of red-tinted photographs from From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried presented adjacent to a photograph of an expansive view of a turbulent Lake Erie from Night Coming Tenderly, Black, is where the impact of the exhibition hits its peak. The pieces reverberate off of each other, creating a confrontation that echoes from the walls. Though these particular projects were made two decades apart, and the techniques used are vastly different, these projects are milestones in Bey and Weems’ careers, shifting the trajectory of their work in the years to come. Here, each of them turned their artistic focus to the past, bringing African American history to the contemporary moment through intensive photographic practice. Any time an artist courageously steps into new territory with their work, as they both did with these projects, it is done with self-awareness, support, and a deep understanding of the field in which they are contributors. These are qualities that are developed in dialogue — with friends, with colleagues, with community.

In the final thematic pairing of the exhibition, “Memorial and Requiem,” Bey and Weems confront violent historic events, using their strengths as photo-based artists to reinterpret these events. For Bey, this resulted in The Birmingham Project, a series of diptych portraits made to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama in 1963. For Weems, this became Constructing History: A Requiem to Mark the Moment , a series of staged photographs that re-enact well-known images of 20th century tragedies, such as the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and John F. Kennedy.

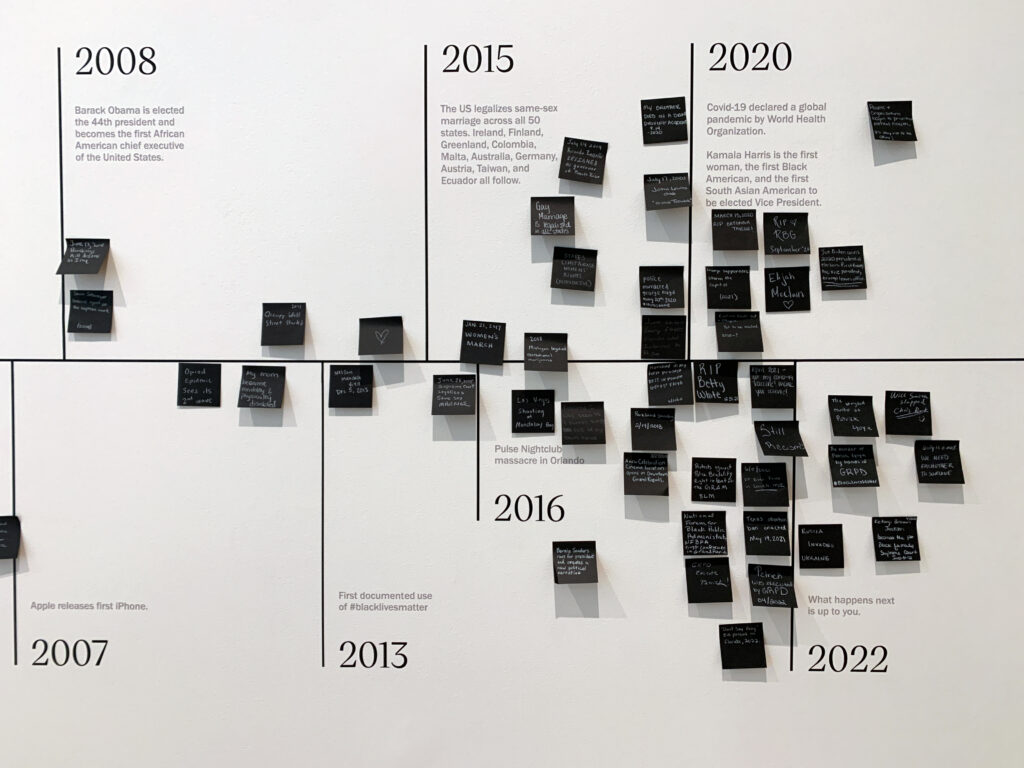

Beyond the galleries of photographs were two timelines — a distinct exhibition element that situated the artists’ friendship within the social and political events that were propelling the world. The timeline included many significant life events, like the birth of their children, and notable achievements, like their MacArthur Fellowships and museum acquisitions. But it is the additional context of cultural events that emphasizes the undercurrent of the entire exhibition: we are a product of our environments and our communities, the good and the bad. Bey and Weems came of age in the 1960s; these were certainly tumultuous times, but also times of potential. On the timeline, marked in the year 1963, many viewers would recognize the iconic photograph from the March on Washington. But also that year, just a few weeks later, the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham happened. Then, still during 1963, the Kamoinge Workshop, an influential collective of Black photographers, was founded in Harlem. Five years later in 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. The founding of the Studio Museum in Harlem was also that year, established as a space dedicated to the work of African American artists. Perilous times, but fertile soil was being cultivated. So when Dawoud Bey and Carrie Mae Weems met in 1976, in a photography class Bey was teaching at the Studio Museum, the gravity of the work they were compelled to create was already in motion.

Adjacent to this chronological timeline was a second participatory timeline, “Our Community,” which provided black sticky notes and white pencils for visitors to contribute events to the timeline that were significant in shaping their own lives. This simple and smart participatory element gave visitors an opportunity to contribute their voice to the museum space, something which Assistant Curator Jennifer Wcisel stated that the GRAM aims to do in all of their exhibitions. More importantly, it encouraged a moment of reflection for visitors to linger and fully digest their experiences. The community timeline, in dialogue with the chronology of the artists’ lives, was also a space to ponder the contemporary events that are shaping artists today. Sticky notes hovering around the end of the timeline included: “Russia invades Ukraine” and “The murder of Patrick Lyoya by hands of GRPD.”

By placing the work of Bey and Weems in these five thematic pairings, a shared consciousness emerges from the walls, evidence of four decades of rigorous work and the sustenance of friendship. In Dialogue emphasizes the responsibility of artists to excavate histories and tell the stories that only they are capable of telling. This is ultimately a question of accountability. When Ella Baker asked, “Who are your people?” she was really asking, “Who are you accountable to in this world?” This is a question for all of us, and it is a question that Dawoud Bey and Carrie Mae Weems have answered through the care and attentiveness they bring to their work and friendship.

Dawoud Bey & Carrie Mae Weems: In Dialogue, which closed at the Grand Rapids Art Museum in April, will travel to other U.S. venues through 2023. It will open at the Tampa Museum of Art in July, followed by presentations at the Seattle Art Museum and The Getty Center in Los Angeles.

Kristie Kahns is a photographer and art educator based in Chicago. Remaining close to her first passion of dance, she has spent over a decade as part of the Chicago dance community through her camera. She is also a dedicated teaching artist, creating analog photography programs for teens. She is currently a graduate student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, studying art education and administration.