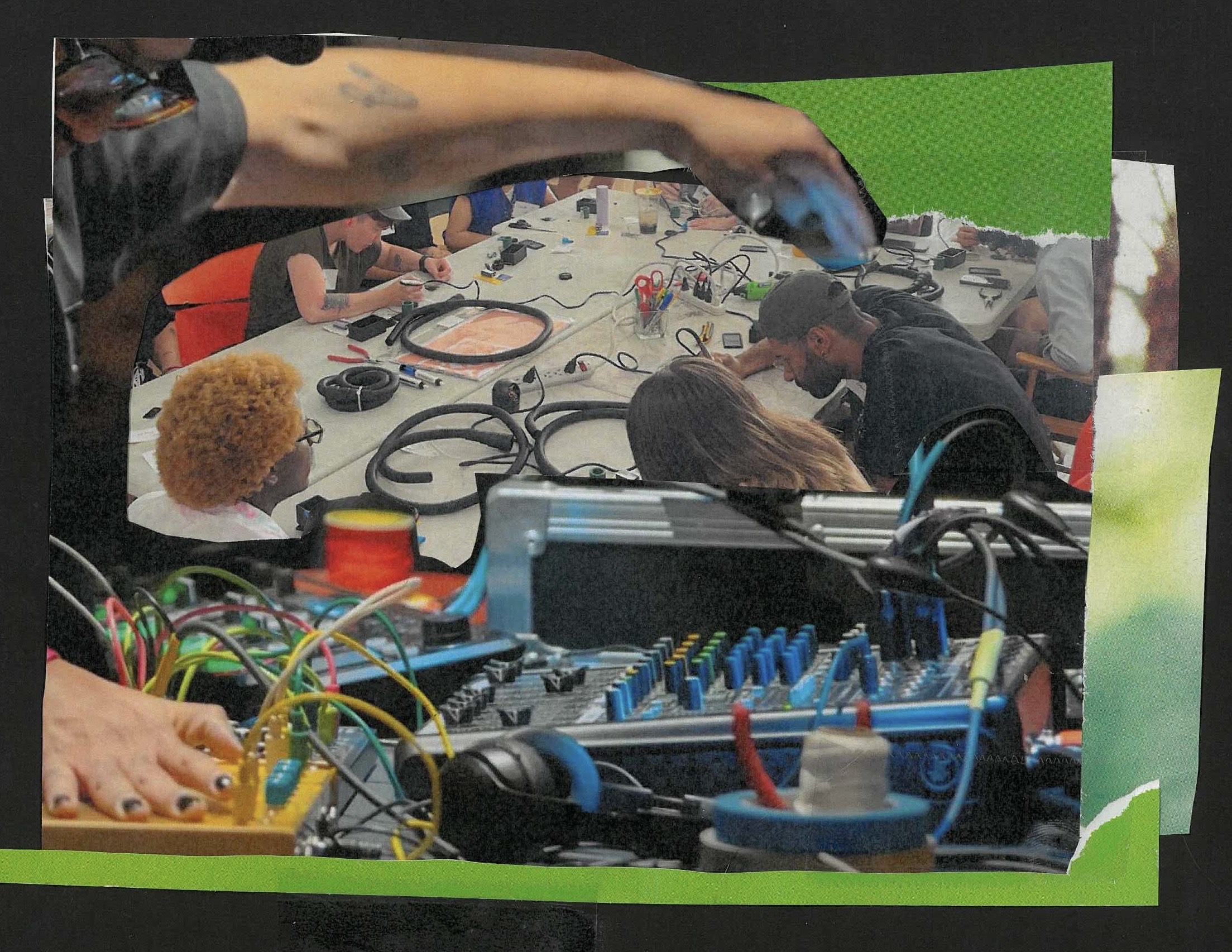

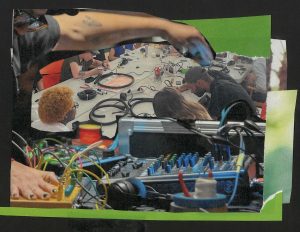

The voice is an outward force, projecting from a body, seeking its place, inciting response. With all of its sonorities, rhythms, and intonations, the voice circulates, but the voice is not its own. As the sound scholar Brandon Labelle writes, the voice is shaped and entangled in “vocal conditions:” power dynamics of linguistic, familial, pedagogic, and political or governmental structures. It is often overheard, underrepresented, interrupted, silenced.1 The voice as a site of intervention finds resonance in the performance EXP/VOX at TriTriangle, where each artist engaged in an experiment, tracing a sonic geography of the voice.

TriTriangle, a space charged with creative history,2 is lowly lit with mostly empty chairs. The artists arranged their equipment on the outside edges of the large red carpet in the middle of the room—centering the audience rather than the artists. Anna Johnson is the first to perform in a series of five acts. Her set is performed in a geometric dome, the oral cavity that is the mouth—a logical place to start thinking about the voice. As George Bataille writes, “The mouth is the beginning.”3

Using a handheld webcam to project live visuals onto the dome, Johnson traces her neck, jaw, lips, teeth, gums, and tongue before and while she sings. The handheld camera maps the voice’s pathway from the interior to the exterior of the body. Johnson explains in a conversation post-performance that her work contemplates “vocalization as a means of locating oneself externally through resonance in a surrounding environment, and also a means of locating oneself internally through the resonance that takes place within one’s body.”

The projections and Johnson’s ambient, fluttering voice transform the dome into a living, breathing entity. The audience observes the voice animating an inanimate object in real time, observing the power of vocal imagination to affect. Johnson’s voice shifts in pitch. The intensity of the resonance has a soft rippling effect like a chain of voices overlapping each other. The voice is no longer one but multiple like a choir. The visuals projected on the dome duplicate in tandem with Johnson’s voice. This performance is an investigation of the voice and embodiment—fluctuating between known and unknown. How are these otherworldly vocal soundings, oral gestures, and the body connected? Johnson amplifies the relationship between voice and the body, showing they are fundamentally nested in each other.

Act two gently begins. Maya Nguyen improvises a rhythm of tics and mufflings that smoothly transition the audience to her performance. Within a few minutes, Nguyen wanders in and among the lying, sitting, and standing audience members. Occasionally, Nguyen lets the word “yum” interrupt the repetition of the sonic texture. In my notes during the performance, I write about the non-linguistic sounds at the beginning as “a crackling or clicking sound, somewhere between the soft sound of bubbles rising to the top of a carbonated drink and a squirrel eating.” I realize I was caught in a trap the composer Paul Lansky described: “your ear can dance while you vainly try to figure out what is going on.”4 Then, like planting daisies in a garden, Nguyen cups her hand and appears to whisper a secret into audience members’ ears. I think about the whisper, the low level of the voice that implies others should not hear or not understand. Labelle asks, “Does a whisper itself point to alternative knowledge whose presence must remain silent?” “Might alternative utterances of whispering lead the way also for alternative communing? In the making of underground societies, invisible territories, and imaginary nations?”5 In a later conversation, Nguyen revealed she was whispering no secret, instead, she opened her mouth next to the listener’s ear. The close proximity between her mouth to the selected listeners allowed them to recognize the sound source: pop rocks.

Nguyen then circles back to a seated area with her instruments and says “I used to walk very loudly, I used to stomp” but “after having a child I walk quietly,” noting the change in the sounds her body makes now cohabiting with her child. She observes her growing ability to coax quietness out of others and continues to express that certain modes of voicing, like quietness, are crucial to survival. Nguyen’s performance, a sound essay, is ultimately a meditation on mothering questions: What does it mean to be a mother? What can we learn about mothering through marked and unmarked forms of sounding?

Whoooooosh. A sound sample from “Surviving in Gaza: Youmna ElSayed on Being a Reporter and a Mom in Wartime,” an interview with Youmna ElSayed, a mother and Al Jazeera correspondent, washes over the audience. “Whoooosh,” Nguyen repeats after ElSayed in a soothing tone similar to how she might speak to a child. “Whoosh,” she explains, is the sound of a bomb falling. “What does it mean to be a mother witnessing genocide?”

Act three. alone-a, a sound project by Alana Horton, submerges the audience in a bath of echoes and sound imaginaries. Using real-time digital sound processing, alone-a transforms her voice into a range of sounds. Working through a Max/MSP program and Neutone AI tool, she creates choir-like harmonies with sinister undertones like a chamber of echoes, sometimes processed into new forms that evoke the timbres of drums. Accompanied by droning tones, her vibrato travels out, expanding, and then doubles back across the space, an echo. Though a familiar sound, the echo takes the voice, repeats, and returns the voice to itself as different, as other. The echo disrupts the stability of a singular focal point, masking the “original” sound. alone-a’s mouth moves subtly, hidden behind the microphone and it becomes difficult to make out the words that are forming. The multiplicity of circulating echos drowns out a clear articulation of words — like they’re wrapped in too much voice. As a listener, I orient myself by way of the voices reverberation as they bounces and stretches across the contours of the room. The space between the vocal source and its meaning widens, creating a generative space to imagine.

After Act three is an intermission. The audience breaks apart and scatters to the street to check on the world and make sure it’s still there.

Act four, maoϴ, a sound project by Ryan ⊥ Dunn, words fall short, the voice tangles with itself, and language collapses into sound. Using a custom-built controller that sits inside the mouth like a retainer, the device’s sensors respond to the movement of the tongue, generating layered sounds—buzzing, mumbling, and fragmented speech—that drift between comprehensible language and pure noise. Dunn also incorporates recordings (which I later learn originate from a hotel room during a previous week of travel). The overlapping sounds, reminiscent of static on an old TV or the hum of a kitchen appliance drowning out conversation, create a tension between the familiar and the abstract. I grasp for bits of meaning within the textural sonic chaos.

Using the repetition of almost formed speech—like those ers, ums, uhs, spitting, tics, or a stutter — maoϴ conveys a narrative of the voice tied to the mouth, a haunted vessel, stammered by language. maoϴ recalls the anxiety of the socializing force of language and how it operates not only through vocalization but also through the body. This plays out through the performance by Dunn the elements of prosody—intonation, timing, and volume—creating shifts in pitch, elongated syllables, and overlapping speech that feel odd yet deliberate.

Similar to alone-a’s use of the echo, I interpret the repetition and doubling (a cousin of the echo) as an opening. As Labelle writes:

“Might stuttering give us this gap, this hesitation, amplified and embodied, performed and tensed, to afford a glimpse onto the profound nature of the speaking mouth? And importantly, a view onto a subject under duress by the force of linguistic order. A tensing of the body under the pull of the voice. Within its tiny repetitions, its clicks and pops, its irregularities, might stuttering put on display this prior to speech, a speech caught in the mouth, this pause, or lag, of a body moved by and moving into speech?”6

maoϴ highlights the tension found in the relationship between the mouth, body, and language. maoϴ depicts a scene of voice as shaped by the contouring of our physical form in opposition to proper speech or grammatical organization.

Act five, Paige Naylor closes EXP/VOX with a performance that invites the audience to an introspective space. Coming after the rich density of maoϴ’s performance, Naylor embraces a softer, more ethereal sound. Equipped with a synthesizer, recordings she made of a tree in Illinois during a residency, and her own voice, Naylor creates a natural landscape for the audience to sonically inhabit. Naylor begins with birdsong, whistling, a gesture to what philosopher Gaston Bachelard calls a “poetics of wings”7 where birds symbolize an uplifting force and evoke an imaginative energy. Naylor continues the performance with a melodic tune, eventually adding the lyrics such as “once you enter/ there is no way out/ so you decide/to rest for a while.”

EXP/VOX didn’t just ask the audience to listen; it asked the audience to reconsider the voice as a sound that shapes our collective interactions. “Everyone who was there that night was participating in an experiment,” Johnson says in a reflection of EXP/VOX, accentuating the importance of expanding perspectives on the voice, and the voice yet to come, the voice that may incorporate more whispers, stuttering, ethereal sounds.

Footnotes

- Brandon Labelle, Lexicon of the Mouth, (London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2014), x. ↩︎

- TriTriangle has existed since October 2012. Before that, it served as a space called Enemy that started in 2005. And before that, it was it was a practice space for Plasticene and Eric Leonard and Eric Lawrence in 1989. That’s 35 years of sound artists. ↩︎

- George Bataille, “The Mouth” chapter in Visions of Excess: Selected Writings, 1927–1939, https://www.upress.umn.edu/9780816612833/visions-of-excess/ ↩︎

- Linear Notes to More than Idle Chatter, CD, 1994. ↩︎

- Labelle, 158. ↩︎

- Labelle, 131. ↩︎

- Gaston Bachelard, Air and Dreams: An Essay on the Imagination of Movement, (Dallas: Dallas Institute Publications, 2011), 70. ↩︎

About the author: Livy Onalee Snyder’s writing has appeared in DARIA, Newcity, Ruckus, TiltWest, Signal, and more. She graduated with her Masters from the University of Chicago in 2021. Currently, she holds a position at punctum books. She’s also a DJ on WHPK 88.5 FM. Read Livy’s writing for Sixty here.

About the photographer: Anna Johnson creates embodied experiences at the boundaries of sound, performance, moving image and installation. Across disciplines, her work navigates intimacy and interrelation on physical, emotional and spiritual registers. She seeks to bring her audiences into states of sensory attention that invite full presence, and is invested in ritualistic live performance as a channel for vulnerability, trance and cathartic release.