“We’re the only ones we can rely on to liberate ourselves…and articulate the specifics of our lives…”

– Kimberlé Crenshaw at the National Women’s Studies Association’s 2017 Annual Conference: 40 Years after Combahee: Feminist Scholars and Activists Engage the Movement for Black Lives

“…my overall concern is with black feminist creativity in general and with the manner in which, in fields like popular music, opera, and modeling, media visibility may be allowed to substitute for black female economic and political power, whereas in more politically articulate fields such as film, theatre, and TV news commentary, black feminist creativity is routinely gagged and ‘disappeared.’”

– Michele Wallace, Variations on Negation and the Heresy of Black Feminist Creativity

When I read the words of these women I’m reminded that I’m not alone in my thinking. The uneasiness or invisibility that I feel for myself and other Black women in different situations isn’t unwarranted or an emotional overreaction. It’s not my imagination playing tricks on me. Within cultural, political, and social spaces, the lack of care, commitment, and consideration for Women of Color (WoC) is often palpable, taking the form of a sticky web of presence and absence that drapes heavily over situations and conversations constantly.

When I argue for WoC to take the lead in the arts, people are compelled to start naming names. They ask, “What about [insert name of a highly visible WoC in the arts here]?” Yes, there are some–several, in fact. When listed (as I start to do later in this piece), the presence of WoC feels significant and undeniable. But as Michele Wallace argues in her essay, visibility does not equal power and it does not protect us from disappearing into the buried alcoves of history. Depending on whose hands are dealing the cards, these examples of visibility can be superficial and sometimes lack the depth to make them feel like a convincing example of our experiences and existence, or hold any sign of authenticity.

Visibility is significant, no doubt, but it’s basic. It’s the low hanging fruit and the easiest thing to do. Sometimes it’s simply tokenism for the sake of ‘good’ optics and diversity initiatives running wild and unchallenged. For example, when choosing an image for a website homepage, newsletter, or institutional Instagram feed, make sure it’s got some PoC in there as evidence that you’re inclusive. Every once in a while, put some extra marketing dollars behind that event inviting important PoC and WoC voices to the mic and the stage (and be sure to snap some photos of that beautiful Black and Brown audience that shows up for them). This is shaky evidence–too shaky to be taken as true care and inclusion.

If that’s the least that can be done, then what is the most–or at least more? More looks like the people behind cultural organizations and platforms being WoC. It can also look like WoC pushing for, making space in, and claiming leading positions at these organizations. It looks like having access to resources and opportunities to build our own organizations, institutions, and platforms from the ground up, if that’s what some WoC desire. The most looks like me no longer needing to write these words and make this case because the examples are clear and abundant, constantly growing and not discounted.

But for now, there is a case to be made. In my opinion and through my observations, there is a noticeable difference when women are at the helm of things, particularly cultural institutions, spaces, projects, and productions. I’m not suggesting that this is always the case, but the amount of evidence that supports my personal theory stacks high. I believe that women, particularly WoC, do things with a particular brand of care and astuteness. Lately, this theory has taken over many of my un-mic’d conversations after witnessing instances of oversight when it would have been useful to have a woman’s touch. New examples accumulate daily.

Unfortunately, it’s when the WoC in my life and I have experienced a form of public neglect, silencing, or erasure that this theory rises (again and again) to the surface. It seems to easily slip the minds of those in decision-making positions that it’s in their best interest to create and keep space for us. They sometimes forget to do this even when the programs are created and framed as being for us, and even when WoC are making the decisions.

In conversation, academia, writing, and documentation, the dominance and prioritization of men–their art, their histories, their accomplishments, their ideas, and their voices–seems to take priority, still. And we too, meaning women, are sometimes guilty of perpetuating that prioritization.

What happens when WoC scholars focus a disproportionate amount of their research on uncovering the legacies of men instead of other WoC? What grounds are broken when women’s stories and voices are uncovered and given room to breathe and connect? I think of the research that goes into exhibitions like We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-85 or Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985, Magnetic Fields: Expanding American Abstraction, 1960 to today, or the upcoming Out of Easy Reach—all exhibitions that focus on showing the vast contributions of women to political and cultural histories while re-positioning their work within national and global art historical contexts. I think of city-wide celebrations like the one that recently left a long spotlight on the expansive influence of poet Gwendolyn Brooks. I think about how baffled the world is by the ceiling-shattering work of women in TV and film like Ava DuVernay, Issa Rae, and Shonda Rhimes, and how thoughtfully they tell stories and build inclusive teams that work alongside them, modeling a way of working for other WoC who follow in their footsteps and forge their own paths–like Sam Bailey and Fatimah Asghar’s Brown Girls.

Many WoC can recite a list of examples as easily as we can call out our own names. The cultural canon is so deprived of these examples that when we see these women recognized on a global (or even city-wide) scale, it feels as nourishing as shea butter on long-neglected ashy ankles and elbows. They seem like exceptions to a tired rule.

Living in a drought like this is rough. Often, one of the only ways that I’ve been able to make a case or conjure up the energy for re-entering or staying in spaces that have proven hostile or unconcerned with WoC issues and ideas is to quietly exchange side-eye or text message commentary in real-time during the experience (“Are you seeing this?”). Other times I work through my unabating vexation in closed company where we make promises to ourselves that we will find more ways and more energy to call out these problematic instances and demand that the people running things do better from now on.

Unfortunately, these demands, proposed solutions, and suggested strategies often come too late, after things have already been organized, exhibited, produced, and presented, leaving us wondering how we can impact the inevitable next time and lessen the normalization of our neglect. Even so, raising the question of how to change this does nothing to diminish our irritation, and as a result it sometimes leaks out of private conversations and into the public realm–even at the risk of burning bridges. Sacrificing a few relationships to speak truth is sometimes a necessary casualty of integrity (e.g. producer Kristen Kaza’s call-out of the oversights in Newcity’s 2017 Music 45 list).

When the response to our criticism takes the form of a wall of defense, the conversation can be halted in its tracks. But at other times, when you’re speaking to people who are willing to listen and confront these concerns, the relationship isn’t sacrificed or severed–it’s strengthened.

The post-call-out climate is a tricky one to navigate. At its best, changes are made behind the scenes–channels of communication are opened, things are discussed, a plan is created, and theory is put to practice. At its worst, the situation becomes a question of how to save face. The ones who are the most vocal around the issues are brought to the table by the institution or platform responsible for the grievance and/or the accuser is offered a public-facing opportunity to address the issue. In this scenario one can feel taken advantage of. When these institutions, platforms, and the people who run them momentarily acknowledge the validity and significance of the concerns, as a corrective measure and in knee-jerk reactionary ways they will sometimes superficially (and cheaply) bring us in to temporarily sit at their tables and solve all of their inclusivity problems, only to have things go back to business-as-usual once the initial incident that sparked the call out fades from collective memory.

Relentless questioning of the platforms, systems, and institutions that exist is one way to continue shifting the dialogue. But there’s also the option of working your way into a position that gives you the opportunity to construct what you want to see in the way you want to see it. And to sneak a small army of WoC in through the side door.

I’m here to share a few stories of women who have or currently are making space for WoCs in various ways, and how they did it.

Move #1: Build Your Own

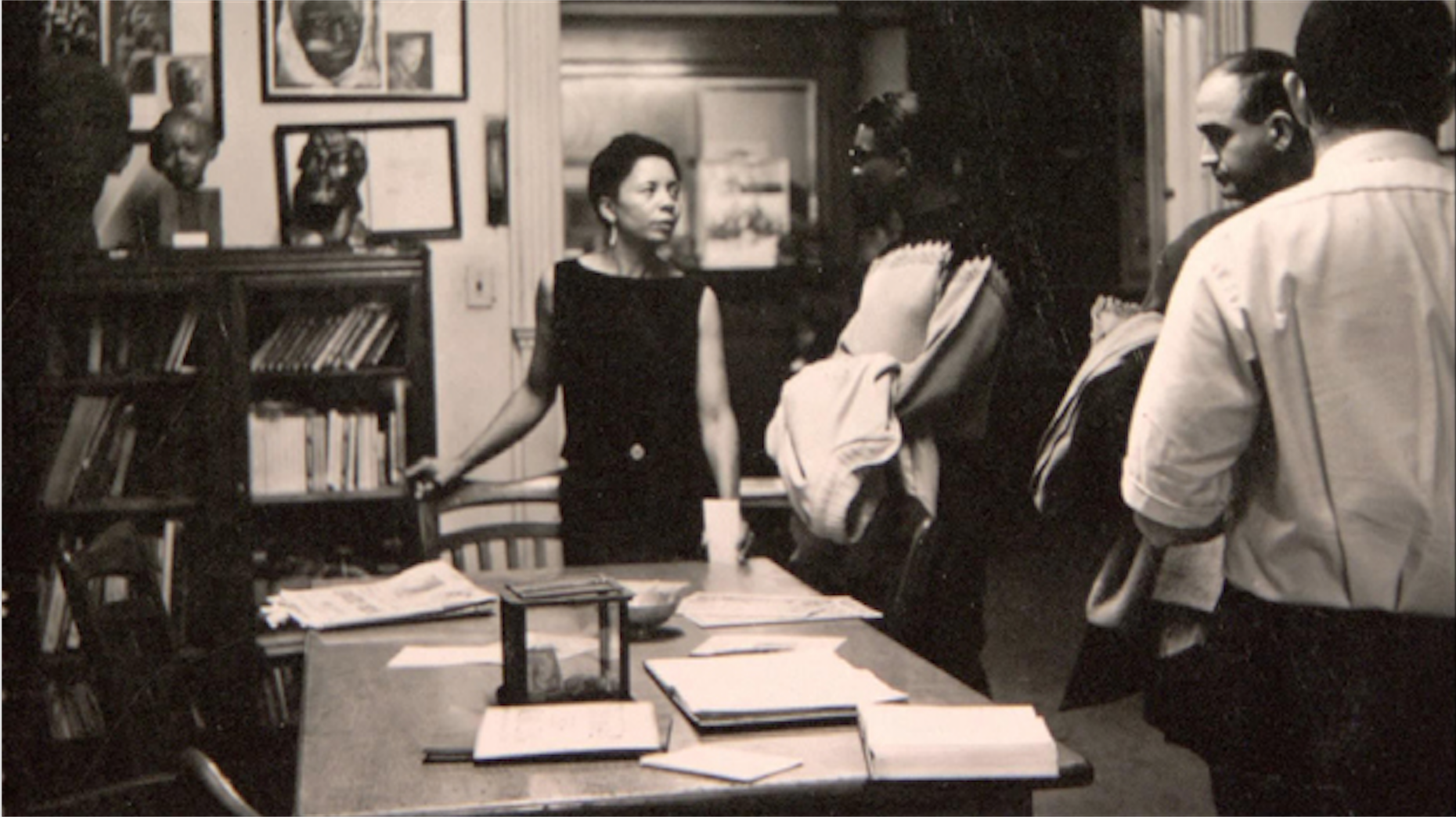

Case Study: Dr. Margaret T. Burroughs and the DuSable Museum of African American History

Throughout history, many WoC have identified blindspots in knowledge and culture, then decided to fill them. At different levels and in different cities across the country, they created new models and examples that help others visualize the possibilities. Dr. Margaret T. Burroughs was one of those women.

In November of 1971, Burroughs wrote a letter to the Chicago Park District asking them to consider gifting one of their unused administration buildings in Washington Park to the DuSable Museum of African American History, which she and a group of artists, educators, historians, and civic leaders had founded a decade earlier in 1961 out of her home. According to Dr. Burroughs, no matter how they renovated it, the museum was outgrowing its building and it was time for them to find a new home that would accommodate their current work and future ambitions. As a poet, Dr. Burroughs was direct yet charming with her words, even though this was considered official business correspondence. The way in which she told the museum’s story, she made it irresistible. How couldn’t they say yes to her request? In her letter to the Park District she wrote:

“…we developed the DuSable Museum, an institution designed not to compete with but to complement and enhance the work of our schools and other educational institutions, one that would be a force for brotherhood and understanding in our city. The response from our community and our city was such as to indicate that the DuSable Museum was here to stay.

Being the first indigenous museum, we became, in a sense, a pilot project and happily, on request, shared our expertise with groups in other cities. Today there is the Studio Museum in Harlem, the Museum of African Art, Frederick Douglass Institute and Anacostia Neighborhood Museum in Washington D.C. Also, the International Museum of Negro History in Detroit, to name a few. Our influence spanned the Atlantic to Ghana where a group of Afro-Americans who live and work there, on hearing about what we were doing in Chicago, petitioned the Ghana government for, and received the use of a Fifteenth Century slavetrading fort which they will develop into an international shrine and museum for the African diaspora.”

Since December 1971, DuSable Museum has called the east end of Washington Park home, in a building that’s exponentially larger than their original location at 3806 South Michigan Avenue.

It was also under her direction that the museum stretched what is considered the work of a history and culture museum. She undoubtedly found exhibition space, a learner’s library, and studios/classrooms to be essential components, but she also believed that art and museums could play a role in the rehabilitation of incarcerated people as well as those living with mental illness. For decades, she successfully carried out a model for what a new kind of relationship to community could look like, going so far as to hold classes, lectures, correspondence courses, and even lend historic materials and objects to prisons and mental institutions for display. DuSable Museum was created as an institution whose priority wasn’t simply caring for African American history, but it was a space to care for and nurture the community as a whole–locally, nationally, and internationally. The chance to build an artistic practice and a career for Black artists was held at the same level of importance as connecting their work and collections to anyone who would benefit from seeing it.

This became the lifework of Dr. Burroughs, whose legacy lives on directly and indirectly through the work of other institution builders like Thelma Golden, whose recent profile in the New York Times motivated me to re-read that letter to the Chicago Park District. Envisioning growth, championing artists, and being of and for Black communities beyond a building’s walls are qualities that both Golden and Burroughs share, along with many other women who are institution builders.

There are plenty of other examples of WOC institution builders who have maneuvered in this way within and beyond visual arts: Betty Blayton Taylor (Studio Museum in Harlem), Laurue Angela Cumbo (Museum of Contemporary African Diaspora), Linda Goode (Just Above Midtown), Suzanne Jackson (Gallery 32), Isobel Neal (Isobel Neal Gallery), Faye Edwards (Faie Afrikan Art Gallery), Nicole Smith (Nicole Gallery), June Kelly (June Kelly Gallery), Tracie Hall (Rootwork Gallery), Ebony Noelle Golden (Betty’s Daughters Arts Collective), Ava DuVernay (Array), Shonda Rhimes (Shondaland), Oprah, Taylor Renee Aldridge and Jessica Lynne (Arts.Black), Mariame Kaba (Project Nia), Page May (Assata’s Daughters), Maria Gaspar (96 Acres), Edra Soto (The Franklin), and Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi (Black Lives Matter).

Move #2: Take it over and take it to the next level.

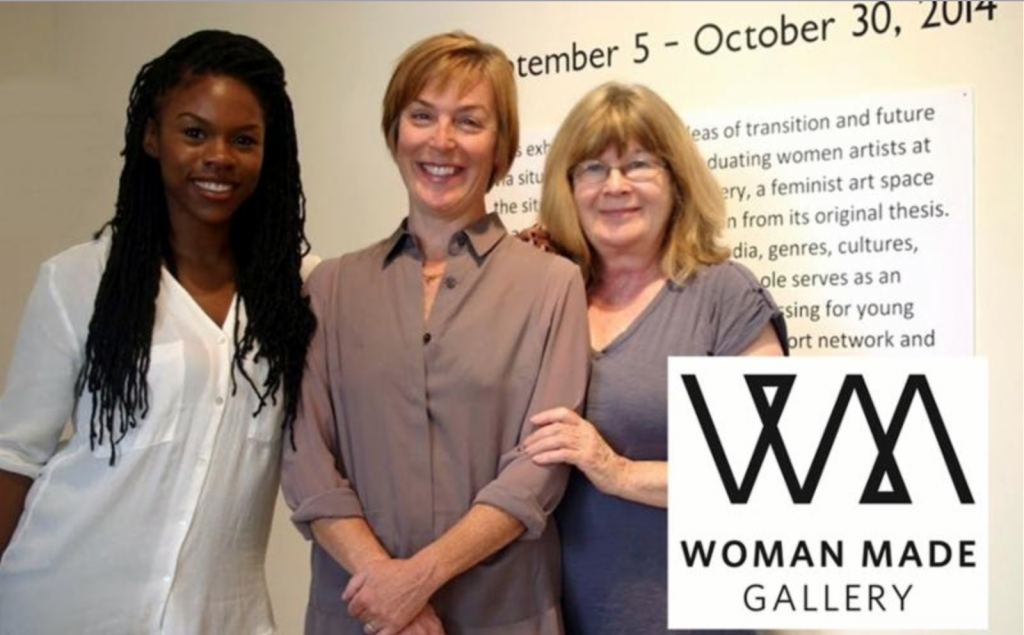

Case Study: Sydney Stoudmire and Woman Made Gallery

As I mentioned earlier, there’s something that happens when WoC are appointed as leaders. When those announcements are made, our ears perk up. We sit, we wait, and we watch because there’s a good chance that she will take it to the next level.

Since its founding under artists Beate Minkovski and Kelly Henson in 1992, Woman Made Gallery has shown over 8,000 women artists from across the globe. Serving as a constant reminder and interrogator of the lacking support and visibility of women within contemporary art’s arenas, this gallery championed and served as a launching pad for the careers of countless women artists.

Although always valued as an important and pioneering space for Chicago and beyond, WMG found a completely new audience after appointing independent curator Sydney Stoudmire to the position of Executive Director. She started off with the gallery in 2013 as the Gallery Manager. Then, after demonstrating wide capabilities and dedication to the organization, Stoudmire was chosen to lead the gallery after fellow curator Claudine Isé stepped down.

Though her time in the position was short (2015-2017), she introduced the organization to a new audience and raised its profile in a way that made it clear that although this was a gallery for women across the board, it was now a space dedicated to uplifting WoC. This is an important shift because, as we know, even in general conversations about women, the concerns of Black women and other WoC are often marginalized or completely absent. Stoudmire was determined to change that.

During Stoudmire’s tenure, she produced and invited others to produce a series of projects that helped to welcome in Woc, including The Aesthetics of Wellness, which challenged the definitions of health that focus on “homogeneous image[s] of young, slim, white, [and] able bodies.” With Abandoned Margins, she invited culture maven Janice Bond in to create a show that brought together artists whose practices investigate supremacist systems and their treatment of the Black female body, directly connecting the artwork to the Dajerria Becton and Sandra Bland incidents. Stoudmire gave a solo exhibition to Janice Bond and also artist Adele Supreme, and uplifted the work of Open TV and Shecrew. She helped facilitate dialogues like Fellowship: Solidarity, and Lemonade Still Steeping: A Dialogue on Movement Making, Black Women, + Social Change. Under her leadership, Woman Made Gallery became relevant to a whole new generation and community of artists and makers in the city.

Other cases worth investigating of WoC who have come in and breathed new life into an institution’s foundation include Naima Keith at the California African American Museum, Kimberli Gant at the Chrysler Museum of Art, Naomi Beckwith at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Angelique Power at the Field Foundation, Yesomi Umolu at the Logan Center for the Arts, Michelle Boone at Navy Pier, Jeffreen Hayes at Threewalls, Teen Vogue’s Editor-in-Chief Elaine Welteroth, and Carolina Jayaram and then Deana Haggag at United States Artists.

Move #3: Stealthily build women into the fabric without writing it on the wall and as if it was the mission all along.

Case Study: Julie Rodrigues Widholm and the DePaul Art Museum

In Summer 2015 it was announced that Julie Rodrigues Widholm would be leaving her curatorial position at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago to become the Director and Chief Curator at the Depaul Art Museum. Already known for her work on the exhibitions Rashid Johnson, Escultura Social, Unbound: Contemporary Art after Frida Kahlo, and one of my personal favorites, a solo exhibition of work by Doris Salcedo, Rodrigues Widholm brought the same dedication to pioneering artistic practices and conceptual musings of contemporary artists to DPAM.

You might not find it written in the mission statement, but she has somewhat quietly and unapologetically changed the demographic focus of the museum as well. As can be seen with the exhibitions she has organized since taking her position, Rodrigues Widholm brought her deep interest in Latin American art and the work of women artists into the museum with her. In the front of the house she’s welcomed in WoC as exhibiting artists and/or curators through significant solo and group exhibitions for and with Bibiana Suàrez, Delia Cosentino, María Elena Ortiz, Dianna Frid (with Richard Rezac), Senga Nengudi, Ângela Ferreira, Hương Ngô, and Firelei Báez.

In the back of the house she has built a team of fierce women to work alongside her, including Assistant Curator Mia Lopez, Collection and Exhibition Manager Laura-Caroline Johnson and Administrative Assistant Kaylee Wyant.

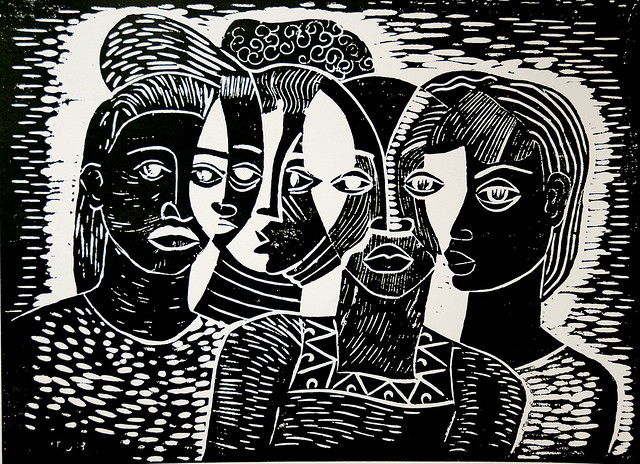

This focus on women, particularly WoC, won’t be slowing down anytime soon, especially with 2018 bringing an exhibition of work by legendary and master printmaker Barbara Jones-Hogu, as well as one part of the exhibition Out of Easy Reach, which spotlights Black women working in abstraction.

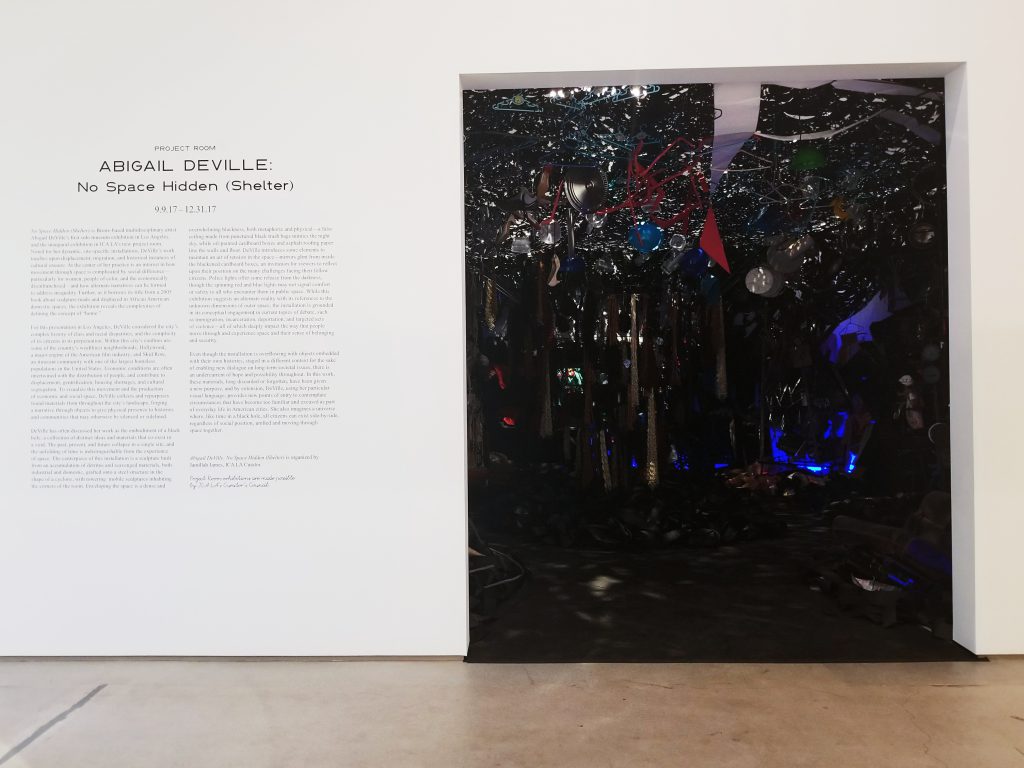

Other organizations that might fall within this move include the kunsthalle-style Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia, which has had a long history of advocating for under-recognized artists, but with the recent appointment of Meg Onli as Assistant Curator, has housed WoC-heavy projects such as Speech/Acts, which “explores experimental black poetry and how the social and cultural constructs of language have shaped black American experiences.” This can also be said about what Rehema Barber is doing at the Tarble Arts Center in Charleston, bringing in artists like Heather Hart and Shelia Pree Bright.

Move #4: Fight for and step confidently into leadership, curatorial, professor, and director-level positions. Claim space on the boards and driving committees of the organizations and efforts that need our voice.

Case Studies: Lowery Stokes Sims (Metropolitan Museum of Art), Deborah Willis (New York University), Kellie Jones (Columbia University), Jennifer A. Gonzàlez (UC Santa Cruz), Jamillah James (Institute of Contemporary Art LA), Erin Christovale (Hammer Museum), Janet Dees (Block Museum), Grace Deveny (Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago), Allison Glenn (Prospect New Orleans), Rujeko Hockley (Whitney Museum), and the list goes on.

This move includes too many examples, making it impossible to choose just one as a case study. Most importantly, it’s also the move that encompasses all of the other moves. The more WoC we include in these roles, the less time that will be spent educating key players on what it means to exist and operate as WoC in the world, and why the fight for the inclusion and equity of WoC is a fight for the inclusion of everyone.

Move #5: Our voices are needed from the grassroots to the penthouse suite, so don’t forget to keep your community awareness wide, your inquiries deep and thoughtful, and your network connections strong.

Case Study: The daily life of many WoC in the arts.

I stand behind the idea that we need to constantly question our priorities as a whole, because when the wheels hit the ground, it’s often WoC who are the ones doing the quiet and essential work in front of and behind the scenes to make meaningful and transformative projects happen, sometimes without much acknowledgement or credit. We can take good ideas and make them great. And we’ve been championing the work of men and institutions who neglect us since longer than I can locate in time. It’s time to question ourselves and interrogate our motivations for perpetuating our own neglect, erasure, and underappreciation while also celebrating our successes. We need to ask ourselves “why?” more often in moments when we decide to write about, research, curate, or invite men to the microphone over or before women, or when we don’t do the research and generate new knowledge about our histories.

I’m not saying that our work must be exclusive to our race or gender–I certainly don’t follow that rule myself. Though I wonder, when we’re at the later years of our lives and we look at the scope and depth of the work that we’ve done, how much of it helped fill the gap, helped generate new talents, helped support and promote the work of women? How much of us is reflected in our work and what does that reflection look like? Is seeing this part of yourself in your work a priority to you? Is that reflection easy to see or is it more invisible and behind the scenes? No matter where your work lies, it’s important to at least ask yourself, “If we don’t then who will?” Alice Walker once said, “We Black women writers know very clearly that our survival depends on trust. We will not have or cannot have anything until we examine what we do to and with each other.” Time has shown how this self-reflection, in its many meanings, is a necessity across all aspects of what we do, how we create, and how our legacies survive. We must not only demand, but continue to model for ourselves and the world the environments that best hold us and our work fully, completely, and with care.

__

Featured Image: A black and white photograph of a room with framed artwork and images hanging on the walls, a bookshelf with small sculpture busts on them. Dr. Margaret T. Burroughs stands at a large table with papers on it, with three people to the left of the image talking and looking at the artwork and material in the room. Photo is takin inside of the original location of DuSable Museum on South Michigan Avenue, circa 1961. Photo courtesy of the Chicago Defender.

Tempestt Hazel is a curator, writer, and founding editor of Sixty Inches From Center. Her writing has been published by Hyde Park Art Center and the Broad Museum (Lansing), in Support Networks: Chicago Social Practice History Series, Contact Sheet: Light Work Annual, Unfurling: Explorations In Art, Activism and Archiving, on Artslant, as well as various monographs of artists, including Cecil McDonald, Jr.’s In the Company of Black published by Candor Arts. Find more of her work at tempestthazel.com. (Photo by Zakkiyyah Najeebah.)

Tempestt Hazel is a curator, writer, and founding editor of Sixty Inches From Center. Her writing has been published by Hyde Park Art Center and the Broad Museum (Lansing), in Support Networks: Chicago Social Practice History Series, Contact Sheet: Light Work Annual, Unfurling: Explorations In Art, Activism and Archiving, on Artslant, as well as various monographs of artists, including Cecil McDonald, Jr.’s In the Company of Black published by Candor Arts. Find more of her work at tempestthazel.com. (Photo by Zakkiyyah Najeebah.)