Tuning Away from Mechanized Listening features Midwest’s music ecosystems—listening cultures where thoughtful curation, collective engagement, and storytelling still shape what and how we hear. This series is meant to be a reminder: listening can be more than a passive, prescriptive experience.

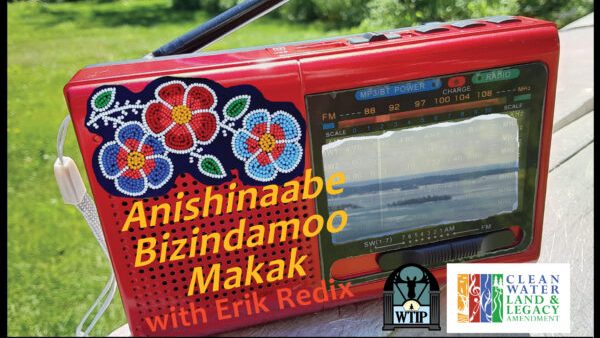

The static crackle of the radio signal fades—not into a commercial, but into the rich tone of an elderly man’s voice, speaking a language that seems to shape the very air it travels through: “Aanin. Boozhoo. Gimaadaadizimin noon gom.” (Hello. Greetings. We are starting now.) This is the opening invocation of the Anishinaabe Bizindamoo Makak, a radio station that broadcasts bilingually in English and the nearly extinct Ojibwemowin language. The radio program broadcasts on WTIP Community Radio (90.7 FM along the North Shore, 90.1 FM in Grand Portage, and 89.1 FM in the upper Gunflint Trail area, Minnesota.) More than a radio program, it is hosted by Ojibwe language coordinator Erik Redix, and features first speakers like Nancy Jones and Larry Amik Smallwood, whose powerful voices echo the weight of centuries. The program is rooted in the rich rhythms of seasonal change and the wisdom of the elders, a living sound art, and a declaration of ancestral knowledge carried on sound waves. It centers on intergenerational storytelling and actively preserves the Indigenous Ojibwemowin language, and Anishinaabe knowledge systems. It reclaims the airwaves as a sovereign space for Anishinaabe cultural continuity and counters frameworks that marginalize oral and embodied knowledge.

As the Sixty series Tuning Away from Mechanized Listening explores Midwest ecosystems where curation and collective engagement shape how we hear, Anishinaabe Bizindamoo Makak is a model of intentional, culturally grounded listening. In this radio program, Anishinaabe elders referred to as gichi-aya’aa meaning great or old beings make use of music, repetition, and onomatopoeia of their indigenous language to pass ancestral knowledge to the younger generation. Ojibwe radio invites us to tune in differently.

Sound as Cultural Vessel

For the Ojibwe people, sound is not just a medium, it is a map of ecological and spiritual relationships. In segments like Gordon Jourdain’s chronicle of Lac La Croix which details animal behaviors in deep snow, an elder mimics the cry of a “binesi,” (the loon) layering it with ancestral stories of winter ice patterns. The loon’s cry becomes a mnemonic device, a living map guiding listeners on how to navigate their way around a frozen lake safely, a vital survival skill passed down for generations.

These sonic techniques are not incidental. They mirror a deep connection to cultural philosophy where language is inseparable from our environment, seasonal changes, and the rhythms of life itself. The radio series grounds its listeners in a temporal framework that defies linear time, achieved not through sonic abstraction, but through sonic layering, the elders’ voice describing ice patterns for instance now merges with the timeless loon cry, which itself carries stories of ancestors who navigated the same lakes centuries ago. It records elders in their homes or near sacred sites, and captures ambient sounds like the rustling of leaves, chirping of insects, and birds singing, contextualizing these voices and sounds within the environment itself. The voices of the elders become the vessel, carrying not just words but transforming broadcasts into archives of multi-sensory experience, carrying words and the surrounding environments that birth and sustain their meaning.

Radio as Ceremony

Ojibwe radio is structured to portray the ritual cycles of the Ojibwe calendar. Its programs are scheduled to align with seasonal shifts. In spring, episodes are centered on renewal, featuring stories about “ising” (maple sugaring) and the return of migratory birds. In winter, broadcasts feature activities such as “aagin” (snowshoe making) or “dibaajimowin” (storytelling), a practice traditionally reserved for darker months, perfect for listening to the elders’ voice, steady, warmth against the imagined silence of deep snow. This intentional pacing transforms radio broadcasts as a ceremonial act, where timing and intentionality are considered.

The use of English and Ojibwemowin creates a call-and-response dynamic that mirrors Anishinaabe teachings. When an elder says “nizh manidoog” (two spirits), the English follows, but the local language lingers. This interplay challenges colonial hierarchies of language, asserting that fluency in Ojibwemowin is not a relic but a living relationship. The show’s producers, who are trained by elders in Anishinaabe oratory protocols, treat sound as sacred. Silence is never empty; pauses are left to honor the breath between phrases, a practice rooted in oral traditions where space allows knowledge to settle.

Sonic Sovereignty

The very existence of Ojibwe radio is a profound act of sonic sovereignty. Born of necessity, Ojibwemowin faced critical extinction—a crisis worsened by the death of its revered elders, knowledge-keepers like Joe Rose Sr. In response to this, the Grand Portage Band partnered with WTIP Community Radio and the Minnesota Historical Society to reclaim the airwaves as a space for cultural preservation and indigenous autonomy. By broadcasting in Ojibwemowin, elders bypass colonial institutions to speak directly to younger generations, asserting control over how their stories and knowledge circulate, reclaiming control over their cultural heritage in the process. This helps them preserve their language against colonial policies aimed at erasing Indigenous languages and voices.

This resistance is a product of collective effort. Elders across Grand Portage work together to ensure cultural protocols are respected in translations and recordings. For instance, when translating stories involving “Mishibizhiw” (the Great Lynx water spirit), elders Larry Smallwood and Nancy Jones collectively agreed that certain passages could only be recorded during “Biboon” (winter) when spirits rest. Producers rescheduled recording sessions to honor this seasonal protocol.

The radio serves as a dynamic vessel, conveying the language and its accompanying cultural heritage into everyday spaces. If the Ojibwe language or any other language is not kept alive, then we will have no identity.

Beyond the Archive

Ojibwe radio serves as a living, dynamic archive — not merely a storehouse of language and knowledge, but a medium through which these are actively performed and transmitted. The elders are not just passing knowledge to the younger generation; they are performing it. Through their voices, language is infused with emotional resonance and culture. In broadcasts, deliberate pacings, inflections, along with the soundscape, itself becomes narrative.

This further highlights the importance of oral traditions in Ojibwe language revitalization, where storytelling and sound are prioritized over static documentation. The sound of waves lapping against a recorded shore while an elder recounts a lake story is not just background, it is an important layer of the narrative, placing the listener there. This is sound art in its most potent, culturally rooted form. It exists not on a gallery wall but in the ephemeral, shared space of the broadcast, demanding a different kind of engagement which is, deep, “bizindamownin” (embodied listening). It goes against the visual bias of western art and the dynamic, relational, and inherently sonic event. “Weweni bizandaan,” an elder instructs (listen carefully). It is an invitation not just to hear words, but to perceive and picture the shape of memory carried within the sound.

Gimaadaadizimin: The Sound of Continuance

Anishinaabe Bizindamoo Makak is a testament to the enduring power of sound to hold, transmit, and revitalize culture. Made possible by the dedicated voices of the elders, the airwaves of Grand Portage have become a vessel for ancestral memory, linguistic survival, and ecological knowledge. They are proof that radio, when wielded with intention and deep cultural understanding can become ceremony, sonic sovereign territory, and profound art.

Minnesota’s state agencies and tribes are increasingly collaborating to support vital initiatives like the Mille Lacs Band’s “Waakaa’igan” Language Immersion Nest for preschoolers and the Minnesota Indian Affairs Council’s teacher training programs at Fond du Lac Tribal College, recognizing that language revitalization in early childhood and community-led initiatives are critical to sustain the Ojibwemowin language. Ojibwe radio offers a radically different frequency. The resonant, living sound of a people, beginning again and again, Gimaadaadizimin, a phrase that resonates far beyond a simple start signal. Within the Anishinaabe worldview, beginnings are not singular events but cyclical commitments. Each broadcast is a deliberate re-initiation of the sacred responsibility to carry language forward. To say “Gimaadaadizimin” is to enact “kinetigwendamowin” which is the persistent, courageous work of cultural continuance, which also acknowledges the fragility of what was nearly lost while asserting the unwavering choice to rebuild, syllable by syllable, story by story, season by season, unifying their language and their world into the future, one carefully crafted syllable, one evocative sound, one heartfelt story at a time. Anishinaabe Bizindamoo Makak is a master class in tuning into the human art of listening as remembrance and relationship.

When the elders’ voices rise from my radio set, I am not just a listener, but a relative remembering my people. My grandmother’s back, bent by years of sugar bush labor, never spoke Ojibwemowin to me. My search for knowledge from school to school severed that thread. Yet in Fond du Lac’s immersion workshops, where breath stumbles “debwe” (truth) and laughter between fellow learners redeems mispronounced verbs, I learned that listening is a kind of homecoming. Anishinaabe Bizindamoo Makak goes beyond sound art or archive, it is a reservoir of blood memories. To write this is not mere scholarship, it is a way of passing knowledge, that every syllable reclaimed is a treaty with the future, an addition of my voice to the chorus: “Geyaabi nindayaan, Anishinaabewiininiwang” (we are still here, we are the Ojibwe people).

. . .

Click here to listen to stream episodes of Anishinaabe Bizindamoo Makak online.

About the author: Umar Ibrahim writes at the crossroads of language, memory, and place, tracing overlooked geographies from Northern Minnesota to West Africa. His essays appear in The Vegan Society Magazine, and dozens of ghostwritten features on health, climate, and education. He shapes stories that balance rigorous research with lived intimacy.

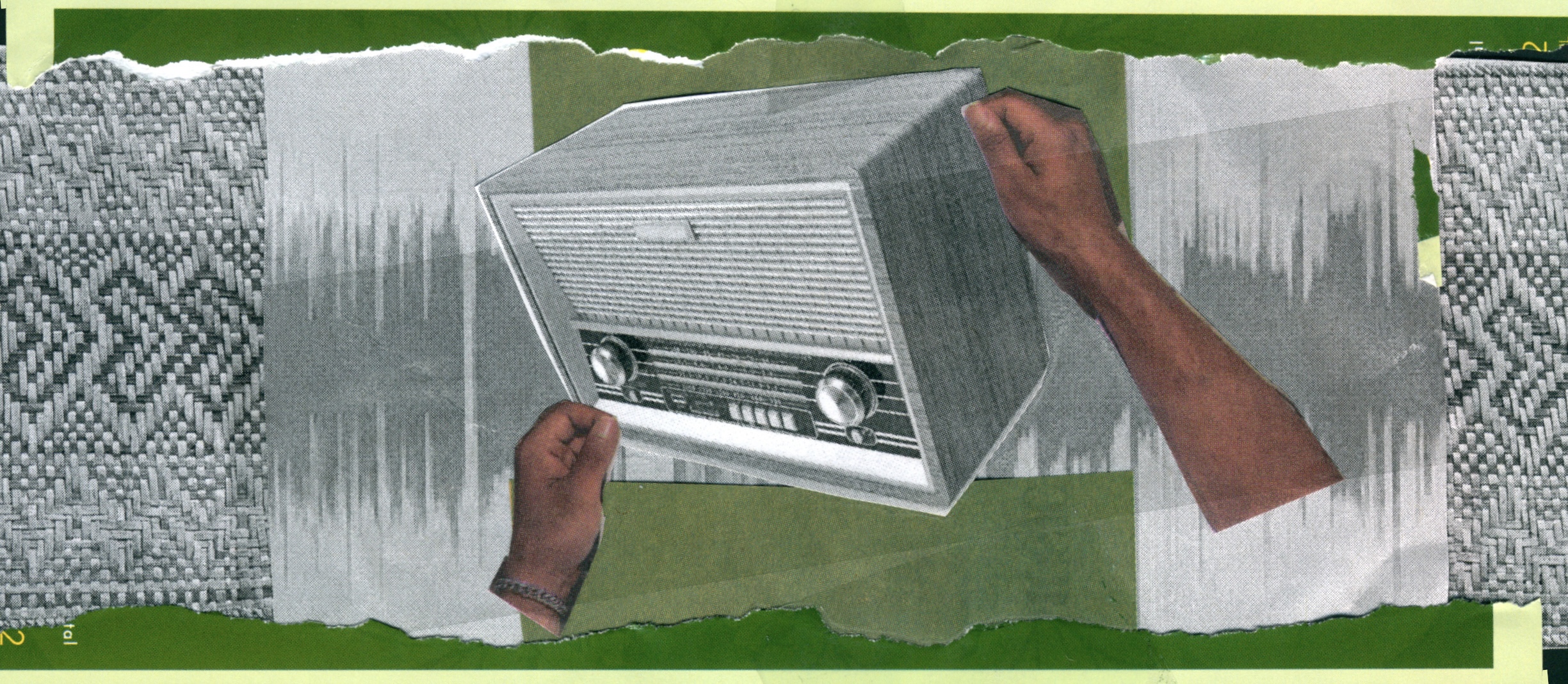

About the illustrator: Bri Robinson is a mixed media artist, analog collagist, sculpture artist, and historian who weaves intricate narratives of love, loss, and identity across the expansive Midwest. Raised in Ohio and now based in Chicago, Bri’s work reflects the rich cultural tapestry of the region, combining personal history with broader societal concepts. Brought up by a large, close-knit family, Bri draws inspiration from the everyday moments and memories that shape our lives, using images found in family photo albums, adult magazines, and personal portraits. Through their unique process of cutting, pasting, and layering, Bri deepens the meaning of these found objects, transforming them into evocative works of art. Bri’s practice is deeply rooted in the exploration of identity, relationships, and the constant evolution of self. By merging archival materials with elements of popular culture, they create thought-provoking narratives that invite viewers to engage with the complexities of the queer experience. Through their work, Bri honors the past while also pushing the boundaries of contemporary art history, crafting pieces that are as introspective as they are expansive. Check out their work on instagram @niq.uor.