This essay was selected through Sixty Literary, a biannual call for literary writing from writers and artists based in the Midwest. You can learn more about Sixty Lit’s inaugural call for writing here.

A map, like a calendar, can be deceptive. Endings, beginnings, and landmarks fit neatly on a sheet of paper or appear as specific coordinates in a GPS. In the Spring of 2021, the clarity of a blue arrow pointing me forward was the kind of certainty I needed. The scope of my road trip from Chicago and back again appears extensive but finite: four months, 7,000 miles, seventeen beds, and two unexpected plane rides. In reality, it sprawled centuries past and moves through me even now, like an arm reaching into the future.

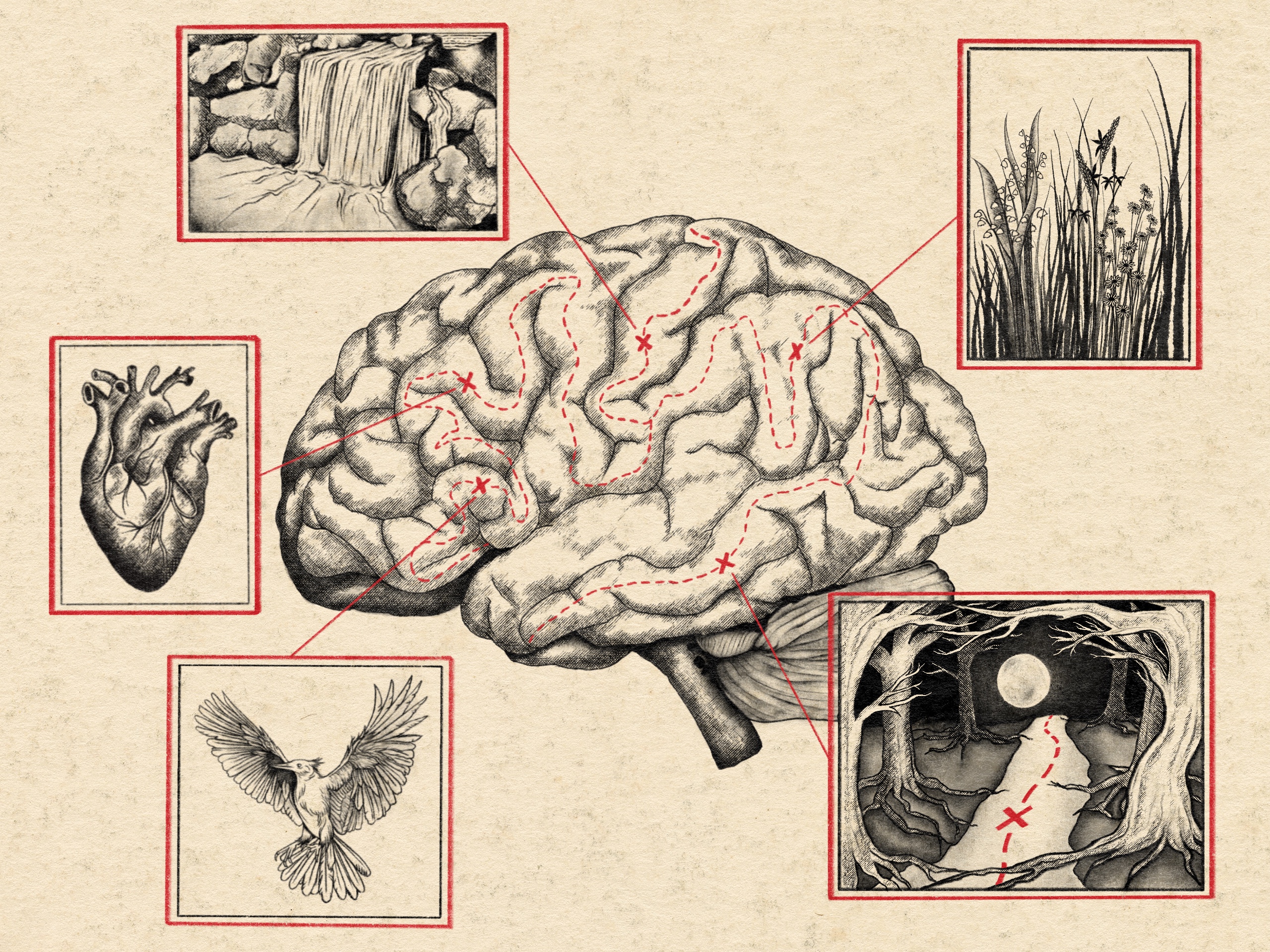

I perceive the journey not as one line tethering me around the country but as a strange, sensory patchwork of memories: the rock edge of a waterfall in Georgia; a quiet Mississippi road with the ominous white pickup truck moving slow on the gravel; the pastel, southwest sunset; the wet, gray sand of a California beach town. Everything I feared forgetting and was forced to remember.

On a cold April morning, I started the ignition of my blue sedan, trunk stuffed with three suitcases and miscellaneous bags, and started to drive.

In the year prior to my trip, I’d mostly stopped dreaming. After dark, I encountered nightmares and the emptiness of forgetting upon awakening. The compounded and seemingly endless traumas of living through a global pandemic and social uprisings following the murder of George Floyd rendered my imagination—in dreams and waking—uninhabitable.

At the start of the New Year, after a long drive and extended visit to see family and friends in Texas, my dreams returned with a kind of prophetic vividness. I felt strange and optimistic that the space in my psyche where possibility lived had transformed from a black hole into a portal.

The drive to Texas and the dreams that followed it sparked the idea for a long road trip that quickly became a plan. I wanted desperately to reconnect with people I hadn’t had a chance to see in over a year and to test out cities I might want to relocate to as a result of my disillusionment with life under lockdown in Chicago. The plan to make a short detour in the Deep South and visit the birthplaces of my maternal grandmother and grandfather offered a midpoint to anchor what otherwise felt like a meandering journey.

The cliché of a cross country roadtrip did not escape me. Although no one said it to my face, I sensed the unspoken: This isn’t something Black girls do. I was grateful that the context of my gender and race spared me from the trope of self-important, scruffy white men in camper vans, but it didn’t endow this precarious trip with any more apparent purpose. The only confidence I had was an urgent desire to feel myself in motion after endless months of stagnation.

Two weeks after receiving the COVID-19 vaccine, I moved all of my belongings into a storage unit and prepared to leave indefinitely. Much of my lodging I booked while on the road, leaning on the hospitality of family and friends, and trusting my ability to figure out the next place to rest as I went.

When I arrived at my first stop in Atlanta on a dead end street overlooking a small forest preserve, I took a breath deeper than any I’d taken in a year. A few days later, I would write in my journal: I’m not sure that this is the best way to begin returning to myself but it is the only way I know how. It is the only way that feels possible.

A friend agreed to fly to Atlanta from Texas to accompany me on the journey through the Deep South. I wanted the emotional support but also the safety of another body traveling alongside me. I knew that visiting the rural corners of these states would mean returning to places filled with ghosts and shadows, but I believed something mystical and cathartic awaited me.

A few days before leaving Atlanta we drove outside of the city to a small waterfall: a central landmark in the internal map I didn’t realize I was constructing.

In her essay, “The Site of Memory,” Toni Morrison encapsulates the ecology and metaphor of water:

“They straightened out the Mississippi River in places, to make room for houses and livable acreage. Occasionally the river floods these places. ‘Floods’ is the word they use, but in fact it is not flooding; it is remembering. Remembering where it used to be. All water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was. Writers are like that: remembering where we were, that valley we ran through, what the banks were like, the light that was there and the route back to our original place. It is emotional memory—what the nerves and the skin remember as well as how it appeared. And a rush of imagination is our ‘flooding.’”

Amidst the quiet roar of the waterfall, I felt something tender open up within me. There was new emotional space to grieve the violence and loss of the last year. In accessing the collective harm of those moments, I felt centuries of harm held in those water-soaked rocks and in the hidden pockets within myself.

A few days later, my friend and I left Georgia and drove to Cuba, Alabama, my grandfather’s birthplace, then continued over the border to Sanford, Mississippi, my grandmother’s. We watched as paint-peeling convenience stores, shotgun houses, and countless farms blurred past the car window. On that sweltering day, the sprawling fields of dark green crops sent a chill through my body. In Sanford, a town of under 2,000, we watched as the old Mississippi flag, prominently featuring the blue stripes and white stars of the Confederacy, still flew boldly from passing cars and front porches.

Ordained in a white dress and curtain-turned-shawl I’d picked up at a thrift store the day before, I posed for photos in an open field with drying bouquets of wildflowers and a photo of my grandmother. I wanted to reclaim something. To leave an imprint on a place my grandmother fled from as a teenager. To serve as evidence of her survival—of our survival—something more long-lasting than the time between our singular births and deaths. With each image captured, the flooding came like broken dams, connecting one part of me to another—the present to the past and future.

In the months that followed, I found myself encountering things I’d only understood in theory. I felt the violence of fossil fuel extraction as I watched automated rigs endlessly pull from the depths of the earth in North Texas, miles of mass violation. I encountered the mountains and canyons that shaped the landscapes of what are now known as New Mexico and Arizona, and ached watching the sacred spirituality of these lands be packaged and sold in tourist towns like Sedona. In the last stretch of my trip I was surrounded by the smoke-filled air of Nevada’s forest fires as a panicked, suffocating sting filled my lungs.

This witnessing was the same kind of witnessing we were all asked to do as records of hundreds of thousands of COVID victims flooded the news and we watched racist violence take one Black body after another. It was the kind of witnessing we were left to do in our friendships, our partnerships, our families, and with ourselves—looking closely at everything we’d ignored or not recognized. As I watched the country flash across my windshield day after day, these ongoing scenes of suffering wove together. The illusions of geographic distance that separated my suffering from others’ collapsed with each border I crossed.

By the time I made it to the northern tip of California, my body was breaking down after three months of relentless transition and a bout of food poisoning. My spirit was tired too—bruised from the displacement and grief that seemed to move around and through me.

Exasperated and tired, I pulled out markers and paper in the office of my small Airbnb and created what I can identify now as a map. The word “harvest” came first. I thought of the sprawling green fields of Mississippi and the backyard garden my grandmother tended to throughout my childhood. I wrote and drew and dreamed, slowly finding my final destination in each scribble: a place where I might know the joy of sharing meals with neighbors, where I might be embedded in spiritual community, where I might plant seeds and pull produce from the fecund soil. I wanted the displacement and separation to stop with me, in me. I’d looked for vibrant cities to offer a pathway to newness and was overwhelmed by the ache of abandoned towns and sacred sites turned into amusement parks. I’d felt a longing for my loved ones and expended the limited of freedom that can be found in separation.

I knew that I could return only if I was brave enough to stay and root. To allow myself the opportunity to become part of an ecosystem with all of the stewardship and investment that demands. To let myself stick around long enough to harvest whatever fruit came from that intention. I sat with the hypothesis that to return might create the conditions for a love so deep it could transcend the inevitable loss that none of us can escape. That I might encounter exactly what I was searching for if only I gave myself permission to return.

Weeks later, under a September sunset, I parked my car again on Chicago’s tree-lined streets and felt at home; or more accurately, I believed I could make this place my home. I trusted that the abandoned and disappointed corners of me could be flooded with memory—painful and tender—helping me return to my truest form: a creature who is connected and loved.

In the embrace of my friend, in the embrace of my city, I felt the harvest waiting for me.

About the author: Jasmine Barnes (she/her) is a writer, community builder, and facilitator based on the South Side of Chicago. With a degree in sociology and journalism from the University of Texas at Austin, Jasmine’s multidisciplinary writing explores culture and identity from a place of intentional witnessing and curiosity. She is rooted in a womanist perspective, centering themes of relational healing, community building, creative self-expression and spirituality in her work. You can learn more about Jasmine and her writing at jasbarnes.com.

About the illustrator: summer mills (she/her) is a printmaker, illustrator, and graphic designer from Chicago. Her work is inspired by the art nouveau movement, religious/spiritual imagery and concepts, music, and various types of literature. For her, the enjoyment of creation is the patience and trust it requires her to practice.