On a Friday night in July, I opened the heavy black door of the Chicago Art Department building and stepped into a sacred space. The energy of the main gallery room hummed with laughter, quiet contemplation and the electricity of impassioned conversation.

piecemeal (earthen works in progress) has ancestral origins. Inspiration for the exhibition dates back to Fannie Lou Hamer’s relentless advocacy for Black farmers, the earth-based rituals sobonfu somé shared in her book The Spirit of Intimacy, and Wangari Muta Maathai’s movement to restore the ecosystem by planting trees. Its concepts and creations are rooted in griot Vertamae Smart-Grosvenor’s vibration cooking and Audre Lorde’s teachings on the erotic. piecemeal is grounded in the tender family photos featured on a public altar and sewn into a quilt. Every piece of art was made in loving relationship with lavender and motherwort and daylily leaves and salty sea shells, the densest of clay and soft crumbling soil. Each element came together piece by piece, leading to this: an ephemeral, revenant and bright exhibition.

In partnership with Contra Corriente, a festival spotlighting the work of artists driving racial and environmental justice, piecemeal was displayed at the Chicago Art Department (CAD) from June 14th to July 26th, 2024. darien hunter golston, a land steward and Core Resident, saw the opportunity to develop an exhibition in conjunction with the annual arts festival. His own artistic practice working with earthen materials coincided with his foray into earthkeeping in 2020.

“Going to the farm and going on walks were like the only two things that got me outside. I needed that medicine,” said golston. “I needed to be out and on the earth as much as possible. Because I couldn’t necessarily touch other people, having that sensuality and touch—with plants, with foliage, with water—was my saving grace.”

This relationship with the earth influenced a series of sculptural pieces golston developed while in residency at CAD: the Fragile Clay Series. In seeking out other artists to collaborate with for the exhibition, golston prioritized farmers, gardeners, herbalists, and foragers who had a deep relationship with the natural world: alexandra antoine, Bryana Bibbs, Courtney Morrison in collaboration with Atoi Glennette & Evéa, Forrest Parks, and saylem mississippi celeste with jireh I drake serving as piecemeal’s preparator. Their creations spanned an array of mediums from textiles to film, sculpture to collage. Themes of ancestral veneration, Black diasporic healing, and eco-sensuality allowed their unique artistic styles to shine through while creating a seamless collective experience.

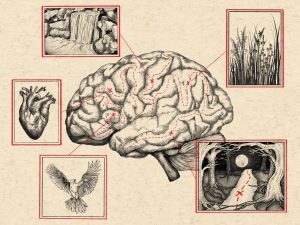

The event I attended on that Friday in July, “Come Alive: a BIPOC-only sensory playdate,” was a community workshop inspired by the short film how to come alive created by Courtney Morrison in collaboration with Atoi Glennette and Evéa. Shoulder-to-shoulder on a bench with other viewers in a partitioned film space, I gazed at images lush with green and brown: plants, trees, melanated skin, and wet earth. A side- by- side shot of brown hands cleansed by water is juxtaposed with a palm, caressing soil. Overlapping roots are transposed over interconnected hands, silhouetted bodies embrace each other and stretch toward the natural elements. Fingers move through coily hair that’s just as dark and grainy as the earth. The carefully crafted soundscape of birds and insects transitions into angelic choral humming.

The film asks: What does it look and sound like when we make love with the earth? Morrison, Glennette and film participant Kiana Lewis, facilitated a vulnerable and tender workshop that invited participants to explore this question and more.

As a viewer, you’re called to find your breath. To feel into what your own lungs and hands need. Watching a person playfully toss a red strawberry into their mouth, I can’t help but smile. A voice speaks as sunlit leaves flash across the screen: The green leaves that kiss me today will shrivel back down into the earth and I will too.

When the screen turned black, I immediately longed for the blissful utopia to continue—simultaneously waiting for the film to loop back to the beginning and aching to go outside and immerse myself in nature.

Similar to the film’s exploration of sensuality, the textile works of Bryana Bibbs and saylem mississippi celeste entice the viewer to reach out and touch. Bibbs, a Chicago-based artist whose practice centers textiles, painting, and community-based practices, incorporates natural materials from the ocean in her art works. Selected from her Journal Series created in Waterville and York, Maine, five woven collages lined the wall under the exhibition’s title card. Each dense rectangle wraps an array of objects including shells, rocks, paper and other objects in a net of hand-spun wool. With dangling threads at the hem of each figure, the pieces look both expertly constructed, and waiting for the exact moment to unspool. A mix of tan, black and blue yarn and varying weaving techniques create a spaciousness and intensity through color and texture.

The skillful composition of each piece invites the viewer to gaze slowly, to find surprising objects, like a plastic name tag or a strip of brightly colored stickers, peeking through the fabrics.

celeste, a multidisciplinary artist based in Detroit, Michigan, contributed their intricate quilts and a deck of twenty two oracles cards inspired by the sourcing process of patchwork quilting. The original digital drawings include cards like #3 “Star-Shine” bursting with yellows, reds and golds and #12 “Grief,” where the color black features prominently, dramatically contrasting the card’s other bright shades and snaking around its border.

Warm colors are central to celeste’s large, hanging quilt at the edge of the gallery. Entitled I Come From A Place of Rage, the quilt includes, at its center, a patch with the word Mississippi and the state’s flag. The flag’s red bleeds across each patch, overwhelming the perimeter of the textile. Other plaid, floral and farm animal fabric patterns allude to rural domesticity. Meditating on the juxtaposed symbols of innocence, I found myself confronted with the contradiction of southern gentility and the state’s history of racialized violence. The piece’s title introduces the word “rage” into the exhibition space, explicitly permitting me to explore my own rage and complex emotions around land as a site of violence, not the orchestrator of it.

Featured a few feet away, a blue patchwork quilt entitled Mother offers up a balm of tenderness with a black and white polaroid framed in orange that features the artist’s mother. The dyed patches of the quilt move from faded white sections to dark blue with rough fringe edges and a partially unzipped zipper. Thin red thread holds the pieces together, complementing the shade of the photograph’s frame.

alexandra antoine explicitly honors ancestors–human and plant—through her mixed media installment, seeds that bore fruit. A large swatch of blue in the shape of a curved mirror, serves as the background for colorful painted plant shapes, an array of floating shelves, and plates on display. To the left, four small shelves are installed vertically with just enough space between them to house a mason jar of seeds. Labels written with black ink describe their contents including “Okra (varieties),” “South Caroline Gold Rice, and “Benne Seeds.” To the bottom right, a slightly longer shelf showcases a display of dried flowers, herb bundles and colorful cards with affirmations. The three plates on display are warm colors that contrast the cool background paint. Each plate includes ornate outlines, like borders drawn on a map, filled with dried plants and grains inviting the viewer to sit with questions of geography, agriculture, food access, and nourishment. A detailed line portrait drawn on brown paper is accompanied by text from the artist. Starting with the line “To the ones that taught me to have a relationship to plants . . . ” the text reads as an ode, praising the many Black diasporic women who shaped antoine’s relationship to food and the earth.

It was a newfound wonder and awe for the natural world that prompted the creation of the exhibition’s oldest piece, five foot four inches forward in the fight for freedom. The title references a quote by Fanny Lou Hammer: “If I fall, I’ll fall five feet four inches forward in the fight for freedom. I’m not backing off.”

golston began creating the peace in 2020 by sewing together dried leaves. The quilted leaves were sewn across the piece and accompanied by acorn tops, paper birch and dried bouquets of flowers. Altar candles lined the edges of the piece and beeswax sealed the structure. For golston, Fanny Lou Hammer embodies the essence of what the exhibition explores: a radical commitment to community, being in right-relationship to the earth, and relentless struggle for Black liberation.

The other two sculptural works on display were Earthen Vessel #1 and #2, part of golston’s ongoing Fragile Clay series. While five foot was a monument in honor of Fannie Lou Hamer, the two earthen vessels were abstract portraits of golston and one of his close friends.

Making each vessel a representation of human beings collapses the presumed distance between humans and the earth. Earthen Vessel #1 features multiple stacked circular clay structures with a living great plant bursting from the bottle sphere. Seeds, leaves, and other medicinal plants are tucked within the vessel and on display in its beeswax-sealed crevices. Earthen Vessel #2 exists as a cluster of organic containers with open tops, overflowing with soil. Dried plants stretch up toward the sealing and two balls of clay fill the space between each container.

The exhibition’s preparator, jireh I drake, brought immense thoughtfulness to the process of caring for each display. For golston’s sculptures, questions arose early about a willingness for the earthen figures to transform during the duration of the exhibition—beeswax melting in the heat, hand sewn leaves and dried pinecones falling off, vibrant green plants wilting. Unconcerned, golston embraced the transformation of the sculptures as central to their creation and purpose. Following the exhibition’s deinstallation, golston returned Earthen Vessel #1 and #2 to the earth, choosing locations that would benefit from their nutrients and biodiversity. Keeping in mind their eventual return to the earth, the sculptures were created with medicinal and native earthen materials.

Basked in the light from CAD’s ceiling to floor windows, a highly interactive and spiritually grounded display invites visitors to engage. Alchemical Memories: Ritual & Scent Mapping, created by multidisciplinary artist Forrest Parks, contains many parts. More than any display, Parks’ work invites viewers to engage their sense of smell. Integrating scents into the gallery experience was an intentional decision golston and Parks made early on to create a comprehensive sensory experience.

A copper distiller, with dried rose petals in a vase nearby, draws your attention first. On a separate table, small vials of the “piecemeal signature scent” are located next to a sign inviting guests to grab one—taking an essence of the gallery experience beyond the four walls. Herbs including lavender and motherwort were harvested from South Side farms and infused into the rich, warm fragrance. Spray bottles of the scent and Florida Water encourage guests to spritz and inhale.

On the central altar space, faded photos of Black folks—embracing, dressed to impress in hats and ties, organized in rows for a group photo—are sealed under a translucent material. These images are displayed on a roughly carved block of wood with soil filling in the empty space between photographs. A large jug of dark liquor infused with marigolds sits at the center of the altar. In the surrounding area, dried flowers, candles, dried corn and a pestle and mortar are presented on the altar space.

The creation of a physical altar inherently provokes introspection and contemplation. Gazing at the tender faces in the altar’s photographs, the viewer is invited to remember the ancestors present in spirit and through the rich brown soil— the form all human life returns to upon its decomposition. Parks’ work invites visitors to “send our prayers up on the rails of incense,” initiating them as co-creators. We exit the role of spectator and transition into active participants, even if just through gesture and intention.

The show’s dedication, penned by golston, acknowledges the myriad influences, named and unnamed, that have helped the exhibition space come to be:

“To the ancestors of the people gathered for this show. To those whose skin matched the many browns of the earth they kept. To those who lived and died tending to the land – by force, for joy, for sustenance, with reverence, through hardship, with ingenuity, in relation – you have my gratitude and respect. We each continue these legacies with dignity & integrity. May this show be a meaningful contribution to our collective resistance and feelings of belonging with the land.”

At the exhibition’s opening night, on the cusp of summer in early June, each guest was offered a single rose. As they navigated the exhibition, engaging with the art and with each other, each person was invited to imbue the rose with their intentions, prayers and reflections. In the center of the exhibition space, the copper distiller transformed those bright rose petals into rosewater. For the weeks that followed, a crystal vase of rose water remained on display with instructions for visitors to pour out libations for ancestors they wished to invite into the space and thank for its creation. On the day of the exhibition’s closing, I found myself alone with the art pieces, crystal glass in my hand pouring out the libations, feeling the mystery and wonder contained in that gesture, in those four walls, and everything beyond them.

piecemeal: (earthen works in progress) was on view at Chicago Art Department from June 14 to July 28, 2024.

About the author: Jasmine Barnes (she/her) is a writer, community builder, and facilitator based on the South Side of Chicago. With a degree in sociology and journalism from the University of Texas at Austin, Jasmine’s multidisciplinary writing explores culture and identity from a place of intentional witnessing and curiosity. She is rooted in a womanist perspective, centering themes of relational healing, community building, creative self-expression and spirituality in her work. You can learn more about Jasmine and her writing at jasbarnes.com.

About the Photographer: Tonal Simmons, they/them, is a Black queer non-binary artist who is a writer, photographer and painter. Their photography and painting seeks to examine the similarities between flowers, growth, and Black queerness. While their writing explores the idea of DEI within art, creating w/chronic conditions, & lack of access to art for Black and brown creatives. You can check out their personal work at www.tonalscorner.com