Art is supposed to be a part of a community. Art is…supposed to be right in the community, where they can have it when they want it… It’s supposed to be as essential as a grocery store… that’s the only way art can function naturally.

The landscape should belong to people who see it all the time.

— Amiri Baraka, “Home: Social Essays”

During the City Beautiful Movement of the 1890s and 1900s, public parks were conceptualized as places of relief from the concrete jungles of metropolis. Their designs included meandering paths, imbued with grandeur. When many businesses were closed on July 4, 2021 and still stricken with COVID closures, my family and I found an urban oasis to enjoy our tea and pastries at Printer’s Row Park. It gave us a common place to sit, gather, and dog-watch. In Chicago, the City Beautiful Movement coincided with The Great Chicago Fire in 1871 and the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 which majorly impacted the development of parks to sprout up among scorched earth and become homes for palatial sculpture, fountains, and plaques. Due to parks being erected by way of collecting city, regional, and national taxes, parks are often publicly owned pieces of land. Despite their intended purpose to provide sanctuary, parks can also divide neighborhoods with the byproducts of urban development, gentrification, and forced resident removal — the story of Garfield Park and Lincoln Park in different ways. Garfield Park was a place of white flight while Lincoln Park had decades of stories of violent segregation and racist tactics by the Chicago Housing Authority and residents of the Northside. Despite the troubled history of parks, what if they were a site of possibility, democracy incarnate? Or even be an intersection for Black creativity?

Urban studies major and nonprofit management minor at the University of Illinois Chicago ‘24, Mateo Baker, who is also my brother, ponders the ratio of metropolitan areas to green space, what makes an effective park design, and how to revolutionize these public spaces for social good. On road trips — long or brief — he’d ask our family of four, “What’s your favorite park? And why?” or, “What elements make a good park?” Parks were places he and I enjoyed newly found freedoms in our youth of exploring the city on our own. One recent assignment he mentioned to me involved dreams of redesigning a Chicago park to have trails emulating the Chicago Transit Authority’s (CTA) train lines.

With my brother’s ideas percolating, I read the email signature of Napoleon Jones-Henderson, a member of an art collective formed in Chicago in 1968 called AfriCOBRA (the African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists). He signed emails with: “Space is the Place!” reiterating Sun Ra’s dispatch into the future. I realized then that parks are (present tense!) the place to create, imagine, and liberate us—parks are a place of gathering and a nexus of the Afrofuture.

When I think about a formative cinematic image of Black creativity in parks, I think of Dorothy (Diana Ross) and Toto being transported into The Wiz’s (1978) Munchkinland. The munchkins appear from the shadows, stumble out of wall graffiti, and then dance, backflipping, kazooing, and playing along to a tune by the Good Witch of the North (Thelma Carpenter). That scene occurs at Flushing Meadows Corona Park in Queens. Evamene, flattened by Dorthy’s house, was the factitious Munchkinland Park’s Department Commissioner who punished munchkins by making them imprisoned in graffiti after creating aerosol art on her park walls. Not only does this subvert the denegation of graffiti and multiple uses of public space, but their liberation brings a dazzling display of resourcefulness, glitter, and charisma activated by movement, fashion, set design, and musical performance.

Beyond the screen, one of the first forms of non-ephemeral Black art in public parks were found in cemeteries, particularly notable in New Orleans with its above-ground cemeteries. The cemetery opened the door to creative memoria for death. For example, Florville Foy (1819-1903), born emancipated to a Black woman and a Frenchman, made marble sculptures for tombs reminiscent of Roman sarcophagi called Child with a Drum (1838). His business in the funerary arts became incredibly lucrative: in 1882, his income was $20,000 (half a million today). Further examples of flourishing of cemetery art in that region, Daniel Warburg Jr., of no relation to Foy and working after Reconstruction, constructed the well known Holcolm-Aiken Family Monument in 1904 out of marble, standing thirty feet high at Metairie Cemetery.

Another high point of Black creativity in public parks includes the Works Progress Administration in the 1930s as social realism prevailed among Black creators, but permeated the country in wartime. Although there are many forms of documentation, such as Chicago’s Living New Deal crowdsourced project and the many meticulous records of art in New York City, the majority of the WPA was an anonymous project. Richmond Barthé (1901-1989) made an exemplary 8 by 80 ft bas-relief carved in stone called Green Pastures: The Walls of Jericho (1939). The repetition of dance-like poses references Ancient Egyptian narrative-based wall carvings and represents jubilation in the Biblical story after which the work was named. This work is located at the edge of Central Park on Fifth Avenue. Many African Americans cloaked their social critiques in Biblical allegories; perhaps, viewers pause at how the work makes the stone look soft and peaceful despite the durability of the material at the end of their park stroll. Still, looking deeper, I wonder if he asserts that the oppressive institutions towards African Americans and Black queer folks need to fall. Or maybe even bow down in the face of Black creativity.

Abstract Expressionism of the 1950s was revolutionary for public park artistry because minimalist and abstract works had a cohesion to nature like never before. Coming out of this tradition, Richard Hunt (1935-) is one of the most prolific sculptors, among many others of public work in parks emerging from this period. From his Tower Hybrid (1979) at Laumeier Sculpture Park, Harlem Hybrid (1998) at Christopher Park in Greenwich Village, and even to Light of Truth: Ida B Wells National Monument (2021) in a park in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood. Kavi Gupta Gallery describes the transformative essence of Hunt’s work:

“As a young artist studying at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in the 1950s, he perceived a Surrealist dreamworld lurking in the junkyards of Midwestern America. The cast-off, metal skeletons of the Steel Age—even then beginning to corrode in heaps across the rust belt—became lifelike abstractions in his hands, perfectly expressing the beauty and terror of a rapidly changing, mid-20th Century American Dream.”

During the Black Arts Movement in the late 1960s to the late 1970s, a revival of a unique brand of social realism, agitprop, spread. This style encouraged many sculptures, murals, and performances. AfriCOBRA believed in bold, ‘Kool-Aide colors, reclaiming African traditional art forms and references, and theorized about the many ways that art launches Black people into the future. Since they originated in Chicago, a place with a long history of mural making, several members made murals enamel-based installations, and distributed artwork in public places across the country such as parks, barbershops, festivals, and stores.

Parallel to the many ways parks had oppressive histories, like the rise of what later became known as ‘Karen’ outbursts, Black creativity boomed and reclaimed public space in the 1980s and 1990s. The public park became a hub for hip hop and voguing. Originating in NYC but sweeping the nation were the epicenters of the underground, subcultural art forms. People would call out categories and participants posed. Chicago has a rich social dance history that migrated from clubs to multiple parks. In 2023, theMuseum of Contemporary Art Chicago honored this history in a day-long event. The MCA describes voguing as a Black and queer “portal for revolutionary and political reimagining.”

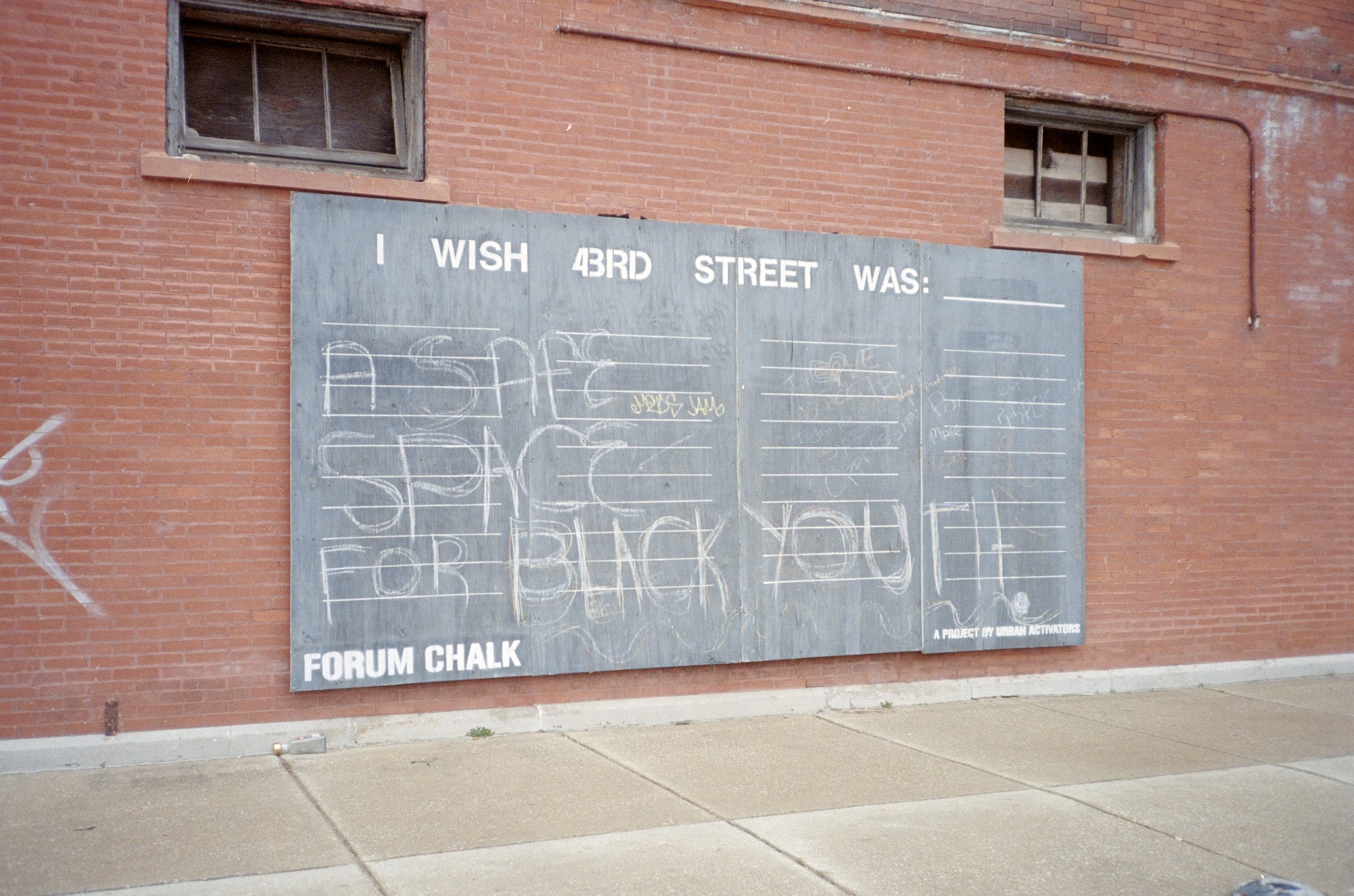

In the new millennium, In Care of Black Women, a Chicago-based organization rooted in the Southside activates vacant sites and spaces for gathering, visual art, performance, and other forms of creatively reclaimed cartographies. The organization proselytizes, “By constructing functionally designed sculptural objects, cultivating land, archiving histories, and curating exhibitions and public programs, we exemplify how communities can repair and reactivate their eco-systems while reclaiming agency over often neglected space.” One of their debut projects was 1148 E. 63rd Street’s former train stop. When that part of the CTA was gutted, the group thought about how to keep the “spirit of the historic train stop.” Now, that lot due to creative placemaking, has become a place for skateboarding and other types of movement-based activities, as well as sculptural seating and a collage wall/library. Through their work, they’ve erected a new park that serves the community.

Another fixture in Englewood is All Power to All People (2021) by Hank Willis Thomas. Located at 5801 S. Halsted—it’s an homage to a phrase from the Black Panther Party about community reinvestment and coalition building. Much like how public art is a participatory experience that bonds us all together. It is a community affirmation and a pillar of collectivization.

Parks have also brought together creative modalities for mourning and healing, to connect back to its history of early African American cemetery artists. For instance, on the ninth anniversary of the police-sanctioned murder of twelve-year-old Cleveland resident Tamir Rice in 2014, the Rebuild Foundation preserved the gazebo made in his honor. It originally resided in Cleveland but the city threatened to destroy the structure. Instead, it is located at the Stony Island Arts Bank. An event for community wellbeing put on by the same organization ushered in the sounds of Frankie Knuckles house music and fellowship at Kenwood Gardens in 2022 and 2023.

Overall, the vast history of Black art in public parks delivers what Jimmy Kirby Sr., cultural aesthetician and doctoral candidate in the Department of Africology and African American Studies at Temple University, calls the “The health of a community is embodied in the beauty of the art. Malidoma Patrice Somé likens the artist to a sacred healer.” Each deliberate artistic conjuring reclaims public spaces for gathering and vitality and asserting we are the past, present, and future!

About the Author: Chenoa Baker (she/her) is an independent curator, wordsmith, and descendant of self-emancipators. She teaches curatorial practice at Massachusetts College of Art and Design. Previously, she led the exhibition program at ShowUp as the Associate Curator and consulted on Gio Swaby: Fresh Up at the Peabody Essex Museum and Touching Roots: Black Ancestral Legacies in the Americas at MFA/Boston. She’s an editor at Sixty Inches From Center, her writing has been awarded the Association Internationale des Critiques d’Art (AICA) Young Art Critics Prize in 2023, and appears in Hyperallergic, Public Parking, Material Intelligence, and Studio Potter.

About the Photographer: Mateo Baker (he/him) is a community engagement specialist and urban designer. As a fellow at the Institute for Policy & Civic Engagement at the University of Illinois Chicago and urban resilience intern at the Center for Neighborhood Technology, Mateo researches proactive climate change solutions. He is committed to promoting social justice and climate resilience through community-led problem solving and urban visualization methods.