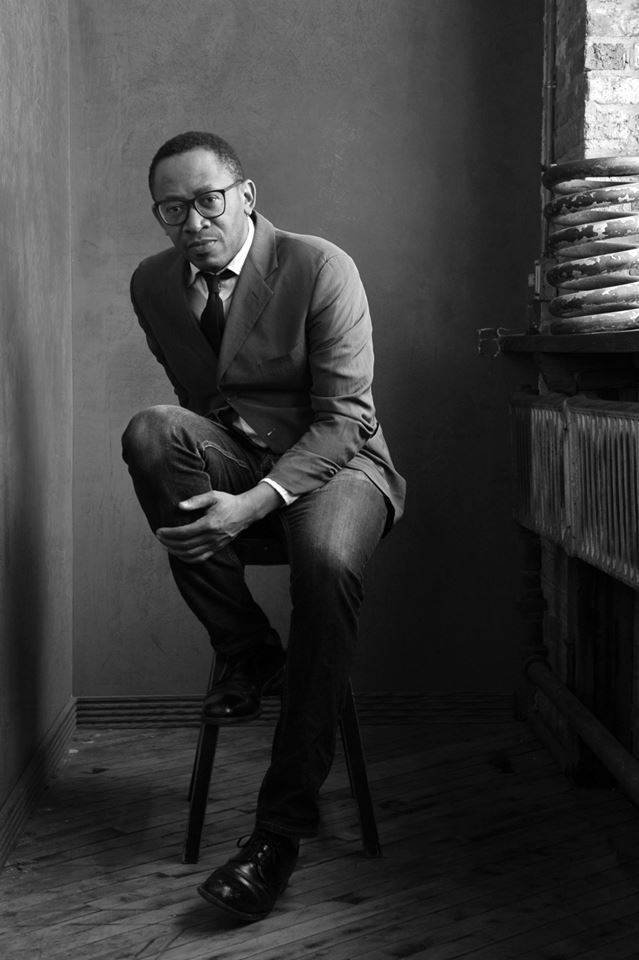

Chicago born and raised educator and designer Norman Teague has been having a moment. Earlier this year, his latest body of work “Reprise,”—a collaboration between Teague, Chicago plastics sculptor Cody Norman, and recycling commander-in-chief Ken Dunn—debuted as part of the U.S. Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale. Having cut his teeth as an architecture student at Harold Washington College, UIC (where he continues to serve as Professor of Design), and the School of the Art Institute, Teague’s rigorous pursuit of blurring the disciplinary divide between art, architecture, and design place him amongst the few visionaries who embody an action-oriented design approach to dealing with the complexity of social change.

In 2012, Teague took part in Theaster Gates’s 12 Ballads for Huguenot House at dOCUMENTA (13) in Kassel, Germany. Exhibiting in Milan at the Salon del Mobile in 2015, he returned to Chicago to present his first solo exhibition at Blanc Gallery in Bronzeville, marking the beginning of his contribution to the city’s Black art and design movement. In 2016, a partnership with artist-designer Folayemi (Fo) Wilson led to the establishment of BlkHaUS studio, a space for social design through architecture, music, performance, and community workshops. By 2017, Teague was invited to advise on the exhibitions team for the Obama Presidential Center, alongside partnerships with the Chicago Architecture Foundation, the Field Museum, and Chicago’s Park District offices, as he continued to mitigate the lack of hands-on arts educational spaces in the city’s South and Southwest neighborhoods.

Speaking with Teague at his studio, I attempted to unpack the designer’s exemplary approach to transdisciplinary practice. Foregrounding community empowerment, asset building, and the right design-attitude needed to serve communities of color, Teague shares glimpses of his journey, growing up in a city that continues to nurture his mission to reclaim and recast design history as we know it in the West.

Pia Singh: We first met after a talk Alice Rawsthorn gave at the Art Institute of Chicago. We were at the steps on a rainy night and got into a conversation about art and design. You’ve come a long way since, congratulations. You were in Europe earlier this year at the Venice Architecture Biennale.

Norman Teague: Yeah, I was there with my mom. It was so much fun. You know, it’s funny. Sometimes you read people that you’ve admired from afar… and then you run into them and they’re [admiring you too]! And you’re like, “Huh?!” Like, I’m even shocked you know who I am! [laughs] So yes, I feel lucky traveling the globe, being in Europe at the salons and events in Venice where you’re meeting people where they’re at, literally… but also finding out they’re wayyyy different than anything you’ve read or seen on camera. [laughs]

PS: This isn’t your first foray into the format of a large-scale exhibition in Europe though. You were at dOCUMENTA (13) in 2012.

NT: That was the first time I put myself on European soil for a long period of time and had the chance to… examine, in a sense, what the art world has to offer me. We were working on Huguenot House with Theaster [Gates] and…it was so revealing. Prior to that, I’d gone to the International Contemporary Furniture Fair and other design shows across the country, but nothing like this.

PS: How long were you there for?

NT: We were there for two months. A whole summer. [reminisces] We lived in the exhibit… wow… It’s a bit of a mind job looking back! It’s even crazier when I think about how I got used to being in ‘my room’. So like, if I’d go into my room to read a book, people would start watching me as though it’s part of a performance. [laughs to himself] We would have breakfast in the morning, as one would in a house, and people would come by and start videotaping the ‘performance’ and calling their friends over the phone, telling them to come over ‘cause “it smells like real bacon in here!”

We went [to dOCUMENTA] to build the house, which was a lot of fun, but a lot of work. We got all the material broken down and shipped and we built everything—our beds, stairs—everything on site for about a month before the exhibit was set to open.

PS: And a lot of these relationships have withstood the test of time I believe.

NT: Yeah, John Preus was there. Tadd Cowen was a master cabinet maker, Nick, Kevin, Titus, Theo… Oh my god, these guys? Friends forever! It was such a brotherly experience.

To be there, to have team meetings, share in our experiences… It was really great to work in this way under John’s leadership, he’s such a great carpenter and craftsman. All this at that point was a hustle for us, but these were also the formative stages of something big, something greater than. It was mysterious in a way, the way this evolved while we were working in Chicago, wondering what’s gonna happen when we get over to Kassel. We’d only seen floor plans and pictures of the building but we didn’t know what condition the space was in, nor how we would outfit the building.

On our very first night, when we slept in the beds we built, it was freezing. Cold as HELL! [shivers and smiles] We were just like, “What are we in for?” By the second day, we were all kind of like, “Something’s gotta give!” This was literally an abandoned building. They had run wiring for electricity and got us plumbing to have a shared shower area (there were time slots for that), but this community of artists had assembled and decided to live together in this building and I think we all wanted it to work. The organizers too were like, “Alright, we need more blankets!” and after a day or so, it got comfortable. Who knows, maybe that first night was just a cold night. But afterwards, I think we were pretty set.

From the article:https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/20/arts/design/plastic-venice-biennale.html

PS: It took on a life of its own.

NT: Yeah, I think there was an understanding that there was still a lot of work that needed to be done. So there was a focus on getting up on time, getting a 6-8 hour work day, and building. A sense of community had started to naturally develop amongst other artists and carpenters working there. It became an extended invitation because other working artists were interested in what an American potluck was and, I swear, we invited maybe 10-15 friends to a potluck at the Huguenot House where we dropped a grill and, of course, someone brought beer. The first night we had about 15 people and two weeks in, there was a line of people to get in! We had a DJ and they were hysterical, “Oh my God, American house music! Funk!” After a while we, ourselves, couldn’t attend the potlucks. The parties took on a life of their own… that’s how beautiful and collective artists can be.

PS: I think it’s so telling about how one approaches the idea of being in community with. It says so much about where you ended up. I like the fact that you weren’t starting with a linear trajectory towards a singular pursuit. It’s also a question of what accounts for being in community—what it’s composed of, what gestures [and] behaviors create that condition? I know that you approach your design practice similarly, and the way you move through the world also considers this.

NT: I think it actually does say a lot about the process that reveals a vision as it forms. Like the common denominator in this particular project was that the community rallied around it, but also that Theaster had strategically thought it out, but also left a lot of room for the “we’ll-see-what-happens” bit.

PS: There’s a term for this that’s described by [designers] Nelson & Stolterman as the fluid seed of inception, the ‘parti’. It’s the viscous nature of parti that leads to emergence in the design process. It’s approximate, never exact and infiltrates at different levels along the way.

I’m reminded a bit of the Indian design concept ‘jugaad’ too, which is translated as ‘frugal innovation’ here. It transpires in a condition of lack or poverty but is really a mindset. Since you’ve recently been dealing with plastics, a material that’s typecast as ‘waste’…

NT: Yeah, I think a lot of people do it, y’know? And they do it because… you just have to make do. It’s not a thing that we intentionally take/want credit for. It’s intuitive. If I was in another situation where I’m forced to use materials around me, whatever they might be, I’d find a way to do it again. Like water bottles (which I hate but have to keep at the studio). Yeah, it’s a space I really love.

PS: Are there moments from your childhood that speak to this experience of material?

NT: I mean sure [laughs] back to my nappy-haired childhood growing up in Bronzeville. [moves his arms comically in a marching motion]

I’m from Bronzeville and if you really think about it—imagine a kid growing up in a neighborhood where you’re asked to play, and the last fun thing that you saw was another kid in a go-kart. You’re like, “Alright, I can build one of those!” So you start to build things that are born of necessity…. You want to have these things, like candy, and you can’t buy it so how do you make it? Similarly, slingshots. We never saw them as harmful so we made them out of rubber bands, a branch I carved, anything I could get my hands on. I think when I got to an age where I wanted more, I turned to [Chicago] Park District wood shops. I had no idea what I was doing there but I knew I wanted to do something. This allowed me to begin to build things and began thinking about craft and making more seriously.

PS: I didn’t grow up here. Could you share a bit about how the Park District woodshops functioned?

NT: The Park District woodshop gave me pretty much the same thing the Art Institute gave me: space, material, equipment, and an occasional piece of advice every now and then.

PS: And what was the age group broadly?

NT: They were mostly older men and an occasional woman. They were either fixing an old thing or trying to build something new. There were boat building classes, things of that nature.

PS: I’ve barely seen any, how many of these were in the city?

NT: MANY. I mean, it was really easy to find a wood workshop at a Park District level. The same place where you’d go to play tennis or shoot basketball, you could actually learn how to make something. People say others weren’t using them enough so they decided to reroute those funds toward more technology. But I felt, and still feel, like those kinds of resources are really therapeutic. I think going to a ceramics class should be as easy as swimming at the lake, because these are things that help us use our senses, our hands, our minds, our imagination.

PS: There is a pragmatist emphasis of learning through doing, the connection of knowing through the work of the hand. In my undergrad, there was an emphasis on cross-disciplinary relationships… like I had to go through metalwork and wood workshop training before I chose to study film.

NT: It’s like asking an architect to be an architect without ever having laid a brick! So the study of the skill, whatever it may be, enriches the process. The work begins to make sense.

PS: In the U.S. though, there seems to be this historic divide over vocational training. I recall it was considered problematic when we were debating what resources the school could offer students from historically marginalized communities. At the time, I was adamant they should offer access to workshops whereas others thought annual trips to the museum made more sense.

NT: Right, but the trip to the museum would only be ‘of value’ if you’ve learned to do the thing, right? It would feed into their experience of what they’re seeing at the museum

PS: Right? Specific to working in community, could you shed light on what you’ve learnt along the way?

NT: Absolutely! I feel like I am blessed because I learned to use my hands and respect the value of that before entering the field. To think about the skills I’d developed prior to going to the [School of the Art] Institute (SAIC). Once I got to SAIC, I was like, “Whoa, I’m gonna have access.” I realized I’m going to have the time to make. At the time, I was 47, returning to school, luckily my kids were old enough and off to college, so they were stable. But I wanted more access—to tools, equipment, to archives and documentation. I felt that at SAIC, if nothing else, they make sure students get access to what they need, and get credit for what they do. I had stories I wanted to tell, I had a lot of imagination, but also I had a lot boiling inside of me. I was mad at how design history had erased people like us, labeling everything that came from us as ‘vernacular’.

[contemplates] I trust my work will be placed on the right side of history, wherever that winds up.

PS: Are there other designers speaking in a similar language or framework as you are?

NT: Not enough, but there’s some great thinkers out there. Michelle Washington is an amazing writer in New York. I think Glenn Adamson has a keen eye on things. There are a few but definitely not enough.

We need more writers of color writing on the work of people of color. It’s been growing since the pandemic, but it’s a bit worrisome. It’s hard to talk about the nature of the work with someone who doesn’t understand where you’re coming from.

PS: Or [who] is casting you in a canon that you’re trying to disrupt?

NT: Yeah, even in the gallery world, I think there’s a need for Black galleries that are also working with objects. I find a lot of them are more comfortable dealing with two dimensional work, so I don’t know… I’m sure someone like Martin Puryear would love to be represented by a Black gallerist, but I don’t think there’s many options for people working in sculpture.

PS: You transgress these boundaries so fluidly, it’s beautiful to listen to you speak on sculpture, art, and design in the same breath.

NT: They are [interconnected]!!

PS: I agree. 100%, they really are! If it’s okay with you, can we go there?

I’m looking at some of the pieces around us right now and materially, designwise, and in terms of what they ensoul, I’m thinking a little bit about how materials speak to you. It’s almost like you can hear them while receiving them in their final form.

NT: I’ve never heard it said like that. That’s beautiful.

I think I have relationships with the materials I work with. Sometimes a story develops prior or there’s a story that drives me to it. For instance, do you recall the balloons on the ceiling at my show at Blanc gallery?

PS: Yes.

NT: The balloons had this lightness to them. Of course, they had lightness in form of appearance and function, but also in terms of weight. At the time I was thinking about them as an homage to all the Black lives that have been lost. I was at SAIC and there was a great deal of… just lack of care for life. There were young Black boys being murdered across the city and it was sitting really heavy on my chest. [Walking down the hallway, we turn into one of several large doors. Norman gestures towards a large sculpture wrapped in a moving blanket.] That’s a self-portrait.

PS: Was that the only self-portrait you’ve made or was there something similar, larger?

NT: This is the only one.

This was another piece that came from the pain at the time I was at SAIC. It still carries a lot of weight. [points to a central columnar form that carries the weight of a circular base when turned on its side] I was thinking about this column as a force within colonialism—the way we’ve been systematically bamboozled for a number of years. [We unwrap the sculpture. The circular form is divided by sixths, forming the shape of a wheel. Along its circumference, it becomes a bookshelf.] You see, the front is shaped like a wheel and speaks more about the ‘good life,’ the admiration I had for fancy cars, forefronting desires that a young, Black man might have.

PS: The aspirational capacity?

NT: Yeah! Like why are young Tyrone’s desires not special? Why are his aspirations not relevant? Can we reframe how we draw a picture of ourselves? I really wanted to talk about how we are situated in the academic world—therefore, the book case. In a sense, I see [the piece] as the past-present-future—where I come from, where I am and who I want to be, where I want to go.

PS: It reminds me a little bit of an Indigenous craft called ‘channapatna’ from South India. The way the column is tiered and tapering. Was this a riff on Indigenous craft?

NT: I’ve seen those spinning tops! But no, this came more so from my background in architecture and my understanding of architectural relief and style that comes from my training earlier. I’m also motivated by artists like Puryear, but I think it was really fitting for the time. I’d like to touch [the self-portrait] again, maybe create a larger version.

[We continue walking from one studio area to the next. The sound of saws and drills drown out our conversation momentarily. We move through studio machinery and detritus]

PS: We went from speaking about listening closely to materials, to your process as an artist.

NT: Yeah. I’m thinking a bit about how to narrate my story a little better. How do you tell the side of your story that meets someone else’s life experience?

PS: But also, you work closely in your community. And in that sense, you become the safekeeper of stories.

NT: Sure, but I’m not interested in keeping these stories for the purpose of archiving in institutions. No, it’s more like, how do you speak in a tongue that actually feels really good to the people that understand you best?

PS: That’s a great responsibility.

NT: Yeah, but it’s like a case of double consciousness as well. What I’m really trying to do is speak the same language to two different people at the same time, so it gets a little messy for sure. But, because it’s your language, how do you learn to speak several languages to get a decent enough understanding from each person encountering the work?

PS: I think this returns to the idea of a fluid parti. Because of its fluidity, it trickles down to different points of the process. When you meet people, where conversations transpire, it propels the process forward. It’s linked to iterative thinking and prototyping—so say you have ‘X’ prototypes and you narrow it down to two. You’ve reached an approximation. Not a precise, exact answer, but something that’s close enough.

I think that’s where a lot of people get social practice wrong. Like an artist is here to solve ‘X’ problem, expecting it can be perfectly answered with ‘Y’ solution. It’s more like the design process where, if you’ve defined the right parameters for your question, you reach the most appropriate or closest possible approximation to an ‘answer’. But it’s never going to be a complete, perfect, or singular thing. It feels unnatural to expect that (and feels very Western and reductivist in ways).

NT: I think there’s age-old answers that come to the forefront, but you know… you’re going to get a different answer from a 12-year-old kid that grew up on the block and a different one from the 80-year-old down the street. I think it’s important that we’re constantly listening, with the preparation to pivot as needed. It’s the same thing that we’re asking from anyone who enters our neighborhoods, anyone who’s trying to validate themselves, to become a member. You’ve gotta remember that, this? This is a club that’s been around for a long, long time. I think people in the community just want to make sure your intentions to be here with them are clear and good. For me, it’s more so a question of ‘What do you want for a future generation?’ And if you’re not thinking of that, or doing it, or part of it, then what are you even doing here?

[Norman walks to a wall with long wooden planks stacked vertically. We see cutaways and voided silhouettes of bases, legs, and armatures one atop the other. The negative forms hold cobwebs at the corners. He dusts them lightly.]

NT: Right now, I’m looking at somewhat ‘junk’ and turning it into things that can be used again. At a certain level, taking jazz and improvisational tradition into consideration. This is probably the most fun thing I get to do, to cut out pieces that are no longer good to some extent and seeing what else they can do. See here, [points along the top left edge] these were leftovers from the Africana chair.

PS: This is where ‘play’ comes in. [smiles]

NT: Yeah! So I literally examine this and think, how does this come back into the world? I just feel like it has so much beauty, language, and other places to go. So I’m playing with these [wooden cutout forms] for a solo show coming up in January at the Elmhurst Art Museum, which I’m looking forward to. [continues walking then stops at a large work table covered in machine parts]

These are castaways too. One of my guys has been collecting stuff from companies that have been shutting down. [touches a large metal cog] This is from a metal gear company that recently closed.

PS: The nature of thrift. You’re integrating found objects that exist within their own realm, are cast off and, in a sense, channeling their potential?

NT: Yeah, I like to think of it as channeling, because you recognize the nature inherent to these things and think, what can be done with these to make new narratives from historical objects?

PS: But it’s the same for people, isn’t it? Everyone wants to be recognized for their strengths. No one wants to be cast off or identified through their weakness.

NT: It’s also for people you surround yourself with, the people you care about. Like you’ll be walking in a neighborhood and see, “Oh yeah, [smiles] I did that. I built that bench where the little old lady is sitting, right there.” And there’s a sense of pride in that. I think, if people can be proud of where they live and how they live, that’s what it’s about.

PS: It really comes down to how we frame our gaze of the ‘other’…

NT: “The Other” ooh.. There’s a wonderful talk by Leslie Lokko titled “I Prefer the Word,” where she talks about this ‘other.’ [shivers] Bone chilling!

[We pass a hardboard cutout of a map of Africa covered in small pieces of black, red, yellow, and green craft paper in wavy stripes]

This is for a high school. Dorian and I made this…do you know Dorian Sylvain? She’s an amazing muralist here in Chicago. I’m working with her on a project to design and build a pavilion for Frederick and Anna Douglass to be built at Douglass Park…something we’re considering ‘rehearsing’ with the Chicago Architecture Biennial.

[We exit and return to the office]

PS: I’m not sure if we got to it, but there’s this intersection between functional design and sculpture. I was wondering if you had any experiences, or processes that you could share?

NT: [hesitates] Yeah, I don’t know. I think it comes really from wanting to have these culturally specific objects, things that point to working with the hand and tradition that’s passed from generation to generation. To me, a basket will always be worth so, so much, because there’s this hand-value, hand-memory, and insight-expertise that is implemented each time someone does this. [points to a basket on a shelf] I, for one, really value and appreciate that. If there was a way to have hand-building at the scale of a barber shop, like if you want to have your hair done and weave a basket while you’re at it—you should be able to experience that.

PS: So really what you’re asking is for the reintegration of craft into life.

NT: I think we’ve become a very plastic society and non-appreciative of what the hand can teach you.

PS: Craft has always been looked down upon—like the lesser child of art and design.

NT: I know, right! So how do we propose living with it? How do we not separate it from the contemporary world that we call ‘Art’ and ‘Design’? I think and feel they mix so rhythmically, y’know? So, returning to the baskets, to plastics, thinking about the tons and tons of it that we have in the world and will soon have to reckon with—it’s something to think about.

How do you think about artists being a steward of renovation, of change, of branding and rebranding of this or that? How do you begin to brand plastic as a material that we can view as valuable as clay or wood? At the end of the day, it’s a material that needs to be dealt with. How do we turn it into something else, something more precious, malleable and value its newness?

PS: It sounds a bit like alchemy.

NT: I think the one thing that flips it on its head is the ease. We now have the means and machinery to collect, or let’s say ‘gather’ plastics that can be put back into the world. There’s this level of machine cooperation that is needed to melt the plastic. You can then create forms for it. You can do tooling if you want to injection mold it.

For me, it’s the freehand gesture of its malleability. That’s where I feel most comfortable playing, because I think it’s most comparable to painting. There’s such fluidity to handling the material that it becomes more like a loosely controlled gestural painting. Even in basket weaving, there’s so many levels of control that you can’t accomplish from this process, but working with a form, you get some direction. In this case there’s webbing that occurs that can also be tied to architecture and allows for a replica of the initial form.

So thinking about how to get a basket is one aspect, but also, how do we get the most from this material so that it can build upon itself? It stacks and bonds to itself like coiling clay where you constantly pinch to bond each layer. Here, you have to get to a level of heat to bond the plastic coils…but it actually happens in a manner of seconds. It’s a slower process that requires a certain level of hand technicality.

PS: For sure, and fluidity. You embrace the improbable. That wouldn’t happen if you were searching for perfection or working with a mold. There’s something to be said about approximation here.

NT: However, that’s no looser than the fluidity of say, a Giacometti. If you look at his sculptures, they offer you these long, slender body-like structures, but to some degree they’re loose interpretations. I think that’s where their beauty lies. Y’know, there’s still a certain form of looseness the hand maintains.

PS: I love the idea of looseness entering because design is rarely associated as ‘loose’—it’s always hard-edge, precise.

NT: Exactly! There’s a drawing you have to follow, so on so forth. So yeah, there’s this in-between place where I think we are willing to go. I think there is also this level where we know we gotta stay loose, because there’s not enough control in this process unless we put it through some sort of tooling path or 3D print. For me, following the handwork that you might see in basketry or coiling ceramics is needed to articulate quality in these final forms. [picks up a prototype] So some of these didn’t tie well together. But ultimately, the word that best expresses these outcomes is ‘exploration’.

I think, honestly, when Leslie Lokko asked me what we needed in the beginning, [when I was invited to the Venice Architecture Biennale] I was like, “Well, if there’s one thing that we don’t have in Black neighborhoods, it’s enough time and money to just explore.” Whether it’s the ideas we have, the conversations, the aspirations. Here at the studio, we glorify fuck-ups, because fuck-ups are a crucial component of growth. You have to have enough room to fuck it up, enough times to get it to that point where you know it’s right.

PS: Totally. I think that also speaks to adaptability. This flexibility we’re talking about speaks to resilience, survival… speaks to a host of characteristics that lead our communities to thrive regardless of circumstances. I think these are all interrelated. Like Nelson and Stolterman’s idea of ‘good design’ was described in terms of ensoulment. It’s the space where people’s values meet the value of an object, it truly captures the soul or heart of the issue and that’s where good design sits. Mind you, we’re not talking about value as a capitalist endeavor but in terms of values of humanity.

NT: This is so wild. I have this picture in my head. [starts sketching] Value meets value but it’s drawn as:

PS: Ahhh…or you could think of it as a mirror image where the ‘E’ and ‘L’ flip.

NT: There’s reflection but…there’s almost this golden sunshine that emits from between.

PS: And that’s the soul…Very cool.

To find out more about Norman Teague’s work, visit the Norman Teague Design Studios website.

About the author: Pia Singh is an independent writer and curator. Born in Bombay, India, and currently based in Chicago, she has organized several exhibitions and public programs since 2010, recently founding by & for (2020), a solidarity initiative that aims to bring together artists, curators and art professionals in support of community-run organizations. Her research investigates community-engaged arts practices through the frameworks of Contemporary Art and Design Thinking, to challenge hierarchies and structures within and outside of which artists form a set of improved conditions in communities, through artistic and collaborative research.