To be either predator or prey seems like an immovable fate; eat or be eaten, in the dark of the woods never the twain shall meet. Whether for Darwin or the capitalist, evolution and growth only take place through domination and mastery. Who cares about migratory birds crashing into buildings in the Loop, Starbucks workers being unjustly fired for exercising their right to unionize? Who cares about unhoused people dying at exponential rates from callow structural indifference, and the city of Chicago barely treating clean air as a shared, public good? Who cares about the old (take a Centrum Silver, babe), the ill (you should have listened to Dr. Oz), the dispossessed (not my fault), the incarcerated (you make me uncomfortable), the children of those struggling to survive (I will immediately call the police on you)? Who cares about the future? Not me, I pay someone to deal with that trash.

If I could articulate the verbal equivalent of an eye-roll here I would. The supposed schism between human beings and the natural world — and the correlated assumption of humanity’s status as apex predator — are neither accurate nor helpful perspectives. These are classifications built on relations defined by industrialization, colonial extraction, death, and destruction. Capitalism would have you believe, no one cares about anyone or anything other than themselves. Such disregard is usually typified in a lack of care for the natural world, because what sums up capitalism more than exploiting, grinding up, and burning the world for spare parts? However, here’s the truth that we can see each and every day: nature, humanity included, is much more intertwined and fragile than those in power would want you to believe. You, me, and the shared land between our feet depend upon this impossible care — because without it? We’re lost.

Artist Deborah Simon’s Embroidered Morphologies is refreshing in content and form because it explores this friction-filled bond between people and the earth, a bond which sorely, desperately needs care that is rarely given. The show features sculptures of toy-sized bears and rabbits, real enough to cuddle, turned inside out, blood and hairless skin exquisitely rendered through polymer clay, faux fur, linen, embroidery floss, acrylic paint, glass, wire, and foam.

We are rarely confronted by a facsimile of animal life not available for purchase or used to sell us food, goods, services, etc. You name it, something cute, fuzzy, and anthropomorphized has probably been sold to you, but Simon’s sculptures are created with startling realism that imbues the exhibition with a sense of the uncanny — can animals ever truly be bought? Viewers recognize Simon’s bears and bunnies as taxidermy, as toys, as art; but their pristine corporeality — skeins of embroidered blood, and unblinking glass eyes — propel the creatures into the realm of the liminal. Simon’s bears and rabbits are known and unknown, they are both manufactured and wilderness incarnate. When you cannot buy, sell, or otherwise master an animal, what do you see? What do you want to see?

Simon takes the bear and rabbit as her subjects because of the emotional baggage humanity places on these creatures, an interesting conceit when examined through the lens of American visual culture. If you contrast Simon’s toy-like sculptures, their blood and sad, unblinking eyes with Bugs Bunny, the teddy bear, the Playboy bunny, and the Charmin’ toilet paper bear you realize something: there is something uniquely American in the way the market encourages people to buy, consume, and deplete the world around them. It is a phenomenon connected to the ever present friction between what is and who are worthy of care. Can you care for an Other that has been transformed to an image? An image that’s meant to be bought, sold, consumed? Real talk, probably not.

Though each bear in Morphologies sits depleted, exhausted, hairless, and raw skin touching the air, their size gives them a sort of ersatz kinship with teddy bears. To whit, American mythology tells the story of Teddy Roosevelt freeing a trapped baby bear on a hunting party, keeping with Roosevelt’s image of a woodsy folk hero, the president who made the National Park System for future generations.

Consider: Roosevelt was president during the Gilded Age, a period in American history where the wealth gap between the rich and the poor was at one of its most pronounced and obscene (second only to our current moment). The Gilded Age gave us titans of industry, robber barons, children in factories, and invisible death for those too poor, too Black, too Brown, too foreign, too female, too different, too powerless for society to notice or care. Maybe we were “given” the National Park System under Roosevelt’s presidency but who was visiting them? People with money, people free to move about the world. For the many, life was nasty, brutal, and short; life was filled with tenements, slums, disease, dirty water, polluted air, and a desperate need for survival.

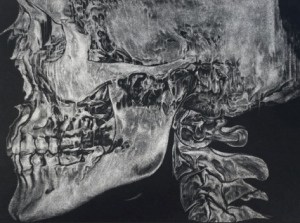

Moving through the histories alluded to in Morphologies is akin to experiencing a haunting; the artist’s Kami series quite literally preside over the space like ghostly witnesses. Each Kami rabbit sculpture is created from translucent organza, their skeletal frames fashioned with piano wire, epoxy, glass, and crystal beads.The kami are installed so that they hang higher than the average viewer’s line of sight. Positioning is important: they see you passively, but you must look actively to notice them floating impassionately within the white space of the museum. In the artist’s statement on the sculpture series, she writes that in the Shinto religion, kami can be thought of as spirits of the natural world. Kami possess no corollary in the global West — this is not a coincidence as capitalism, products, buying, selling, and striving contrive to kill whatever sacred exists within society. The closest approximation of kami are spirits neither positive nor negative, but haunting presences that exist in all life, human and beyond-human.

To be haunted is to be marked by experience; it is the world changing you and you changing it in return. Simon’s Embroidered Morphologies shows the consequences of power, humanity’s heavy tolls. We are linked: the world, you, me, everyone you know, everyone I know, the people neither of us know. In every line of embroidered blood, every glass pupil, every tender patch of skin, Simon reminds us that this too — you too, we too — shall pass. We’d do well to heed her.

Deborah Simon: Embroidered Morphologies is on view at the International Museum of Surgical Science from January 27 through April 23, 2023.

About the author: Annette LePique is a Lacanian.