This article is presented in conjunction with Art Design Chicago Now, an initiative funded by the Terra Foundation for American Art that amplifies the voices of Chicago’s diverse creatives, past and present, and explores the essential role they play in shaping the now.

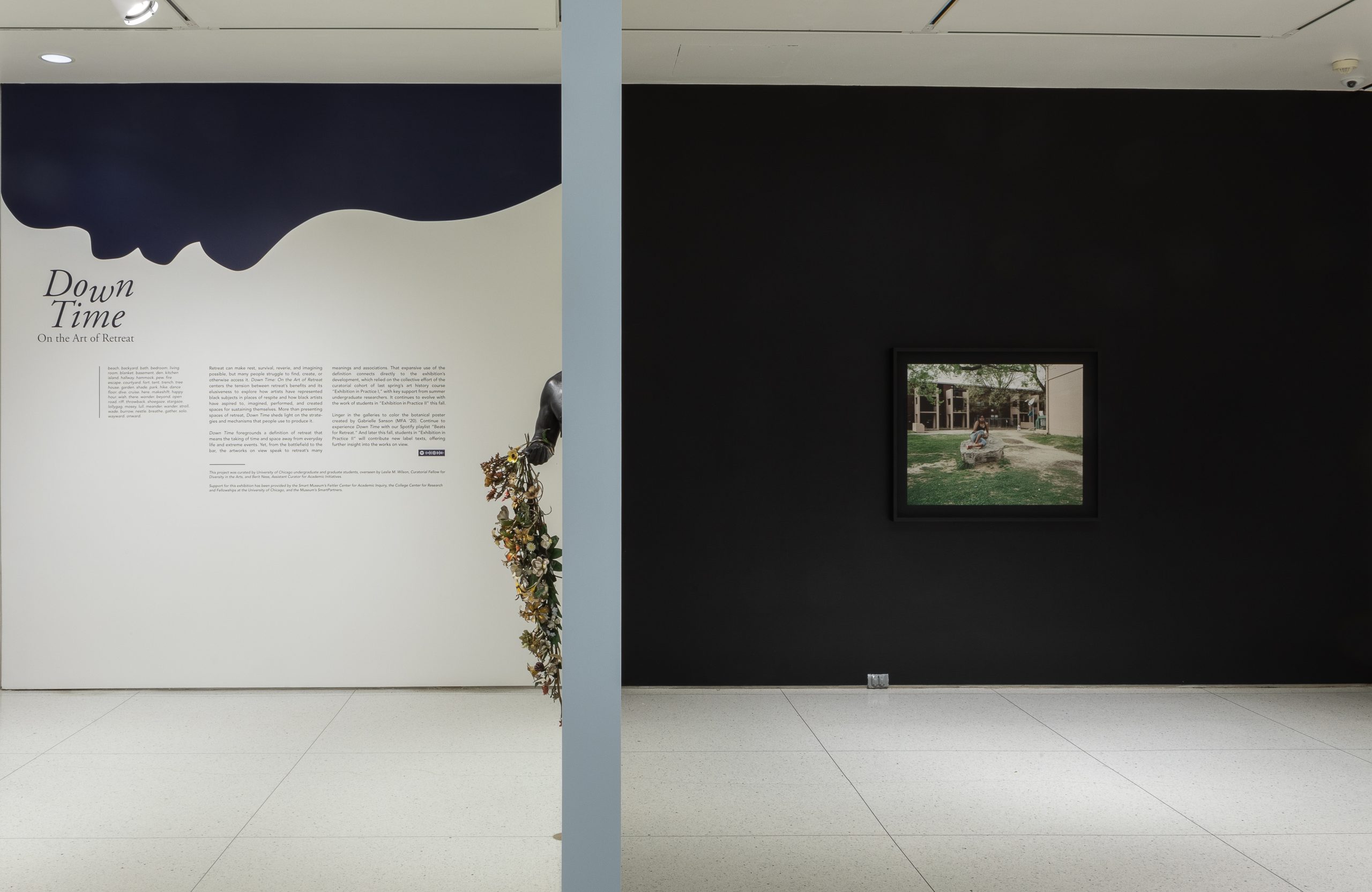

“Where can we turn when we need space and time away? What do those spaces look like, and how do we create them? Who has access? How does resting mean different things depending on who is doing it and who is representing it? How does “getting away” shape an ultimate return?” These are among the questions addressed in Down Time: On The Art of Retreat, which was on view from October to December of 2019 at The Smart Museum of Art.

The show, which pondered the idea of retreat from temporal, political, historical, and somatic angles, brought together a cast of intergenerational artists including James Van Der Zee, Romare Bearden, Faith Ringgold, Patric McCoy, Carrie Mae Weems, Lorna Simpson, Ja’Tovia Gary, Derrick Woods-Morrow, and more.

The genesis of the exhibition was, from end to end, a collaborative effort between undergraduate and graduate students at the University of Chicago. Together they worked under the tutelage of Leslie Wilson, the now Associate Director of Academic Engagement and Research at The Art Institute of Chicago.

I connected with Leslie after her talk Making Down Time, which was presented by Red Line Service as part of Art Design Chicago Now. Below, you will find our conversation about the delicate process of creating exhibitions that simultaneously begin with an inquiry about identity yet also refuse what Wilson calls “troublesome looking,” the challenges and triumphs of collaboration, the irony of curating an exhibition about retreat only months before the beginning of a global pandemic, and the tough yet deeply rewarding work of bridging theory to praxis.

Camille Bacon: I’m curious about how you came to the idea, the concept for Down Time: On The Art of Retreat. Why did curating that show at that moment feel urgent or important for you?

Leslie Wilson: [The exhibition came out of] a class that I was asked to teach by Ali Gass, [former Director of The Smart Museum]. She and Issa Lampe, [former Deputy Director for Academic and Curatorial Affairs and Director of the Feitler Center for Academic Inquiry], asked if I would come back and teach an exhibition practicum and I was like, all right, how will this work? And, you know, what will this be?

It was also a class that was open to undergrads and grad students. So it had students who were from second year in undergrad to Ph.D. students, a real breadth of experience. But what would it look like for all of us to make a show?

We made the show incredibly fast, so we were building [it] in spring into the fall and it opened in October. It was half loans and half from the collection, which was bonkers.

[The goal] was [also] to really sit down with students and ask them the question of “what are the merits of building any project that thinks at the beginning about identity?”

CB: Absolutely.

LW: Is that something we want to do? If we take our lead from artists like Adrian Piper, we could ask questions like “who is comfortably raced”?

CB: Yes, yes!

LW: So then it’s like we’re already starting in a problem and then how can we activate that problem for students to say, “let’s look at some work in our collection” and [consider] what does it mean to think about Blackness in the collection? And then we’re not just looking at makers of color, we are looking at anybody.

So we built a list that took you everywhere from Kerry James Marshall to Walker Evans. We had [students] look at the history of the Smart Museum [more broadly] and its exhibition history. Thinking in recent years about shows like The Time Is Now!, and Solidary & Solitary and saying, well, it’s not the Smart’s first show that focuses on Black artists. We’ll see a lot of institutions where it’s the first show. You know, [they] want to make a splash. So, what I told the class was that we could do a B-side show. [We could] go somewhere else with this. But do we even want to do a show that’s thinking about identity? So we were kind of reading into that problem through the quarter. And then students proposed exhibition ideas and we ended up making an amalgam [of those proposals].

It was 13 students, all with different ideas and things that were driving them. There was a group that was interested in a show that was thinking about race and privacy and thinking about some recent events on UChicago’s campus. And then there was another group that was really interested in Afrofuturism, for instance, and another group that was thinking about art and grief and mourning. There was real discussion in that room about like, well, we don’t want to do a show where we’re reproducing certain forms of troublesome looking. What can we do to intervene in that? So we had really wonderful discussions.

The one word we could all agree on was “retreat,” the one thing that kept coming back in discussions, especially as it relates to Black subjectivity. [With that context in mind, we wondered] who can get away? What does it look like to get away? But then there was also this pernicious question at the base of all of this, which is, is there an escape from race? Is there an escape from racial violence?

And then there was a sense of like, can we claim to know what retreat is for anybody? And if we maybe absorb the humility that we can’t know that, then maybe the work can offer some opportunities. And so we really kind of worked through that arc of difficulty. As a class, we shared that sense that you can’t leave the difficulty out.

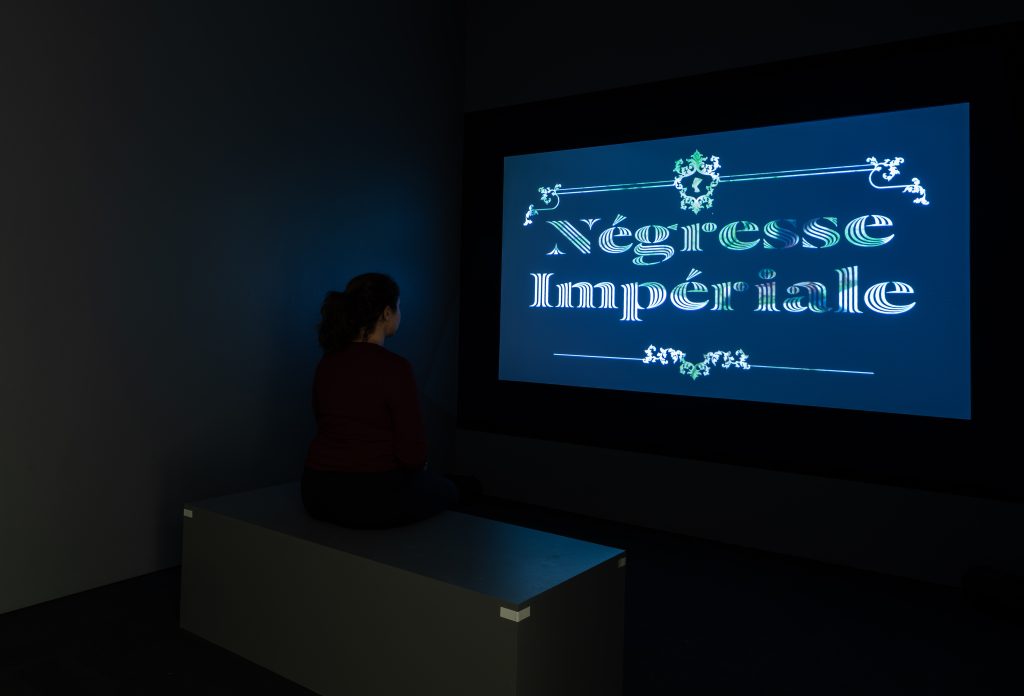

And so some of the most challenging work that we really wrestled with was work like Ja’Tovia Gary’s Negresse Imperiale. It was a work that felt really important in our class debates around, you know, how did Ja’Tovia use the residency experience at Terra to examine retreat itself [in Claude Monet’s garden in Giverny, France]? And even at maybe our most quintessential sites of artistic retreat, how does the world refuse to let us go?

I met with a friend, the wonderful Mlondi Zondi, for coffee and I was talking about some of the issues that students were raising and feeling my own stress about like, am I going to shepherd this project well?

[I was expressing] some real anxiety about [the ethics] of reproducing images from traumatic events in the show, [for example]. [Mlondi reminded me about] Harriet Jacobs making this hole for herself. She’s hiding to see out into the world. And she does that with what she refers to as a gimlet. I had not remembered the story like that and Mlondi brought it back and was like, “If your show is doing something right, I don’t even know if it’s about the loophole. It’s about the gimlet. It’s about the device.”

CB: … the device that you use to make the retreat possible in the first place. Right.

LW: How do we make a space for ourselves, while also facing life’s realities in those zones that feel absolutely impossible? And [Jacobs], she makes a space of possibility. She makes a space for imagining. She makes a way for herself.

And then it’s like you’ve stopped overpromising. You’re interested in a way, you’re interested in the mechanism. And so that became really exciting for the class. And that became something to really spin around and think about. And work like Ja’Tovia’s suggested “a way.”

CB: One of the things that really struck me is how tactful the framing for the exhibition was. By asking this question about ‘retreat’, you veer away from that idea of “troublesome looking” you mentioned. I interpret that as this move where spectators encounter a work by a Black artist, and then delimit their interpretive frame because they expect the work will inform their understanding of “the Black experience,” as if any one artwork could ever speak to the vastness of something so inherently expansive as Blackness.

And so I wonder how one can tactfully question how Black subjects, in particular, experience or don’t experience rest and retreat? And how do Black subjects relate to that question as a way of asking much larger questions about how our current conditions obfuscate opportunities for rest for everyone? I wonder if you could just talk a little bit more about that tact and why that tact felt necessary.

LW: This was at the base of some of the really good discussions in class and debates. The group who proposed an exhibition on race and privacy, one of my questions to them directly was I was like, okay, so this is really interesting, but how are we going to resist certain scopic machines that you want to critique?

But it was to say that, you know, do we have to look at a certain kind of problem to raise the problem? And I don’t know that we do. Can we assume the problem and go from there? A certain way of looking, we don’t need to see it. We’ve got it. We live that look every day. We re-perform it as much as we resist it if we’re honest with ourselves.

And we found ways to think about this through the work in the show, through the really exciting ways that younger artists like Derrick Woods-Morrow are drawing us into these problems, asking us what does it mean to push the dark as far as it will go and to really think about these spaces where darkness and Blackness create their own poetry.

But then I also wanted us to acknowledge that we were going to make certain decisions on the show that work for us at this moment in time, and five years from now we might think radically different things.

All exhibitions are experiments. It’s always a petri dish. So you’re running an experiment and as you see people interact with it and you see them respond, that’s your data. You’re collecting it and you’re understanding the show better. You’re looking at it more as it’s going. And so one of the things I asked the second half of the class to do was to suggest a work that they would pull out of the show and work that they would add based on their experience of the show.

And some of that was about formal things that were happening or just like not a great use of space who felt forgotten or lost. But a chance to say, “no, no, no, this isn’t done yet.” I’m still thinking about this. And it’s really done something exciting for us. It’s raised issues that aren’t resolved, and then that’s your next project.

CB: There we go. I feel like I have to ask about the context of the pandemic too because I think one thing it illuminated was the breakneck speed that we were operating. The pandemic gave many of us a chance to consider that more thoroughly and, in response, slip into new rhythms. Of course, that was occurring within the larger context of the world burning in literal and metaphorical ways and I think that reconsideration of time was perhaps part of the burning. All to say, the themes you and your students took up in this show were played out in real time very soon after it closed. And I wonder now, how do you reflect on the supreme irony of making a show about rest, retreat, and downtime that closes right before the beginning of a global pandemic?

LW: It was wild. It was really wild. I mean, I think it felt like it had predicted something.

And it was also strange because there was a real yearning to be back in the world. But one of the governing ideas of the show was questioning what retreat makes possible in the return. Like, how does having to change something about your way of working, of stepping away actually help you renew or restore or think differently about something?

It did help make possible a certain kind of looking at phenomena because people were inhabiting their lives differently. I thought a lot about that shift of attention. Like, what a certain kind of upset or change can do? But also a sense that there might be a little bit more time for people to do that looking and contemplating. So I don’t know if that was downtime, but it was a different kind of time.

And something I kept thinking about in the show afterward was what does it mean to be anti-time or against time, right? That a lot of what we were exploring might be considered a misuse of time. You know, if one looks at models like “colored people’s time.” Yeah, the idea of a certain kind of slowness. My family is from Jamaica so like, ‘When is soon?” in the notion of “soon come.”

CB: Yeah! Same in Martinique, where my mother’s side of the family is from. Same thing. You can tell people to come at noon. They show up at three and there are no qualms because we’re all inhabiting a sort of sticky time that glues us in the moment.

LW: Something we also talked about in class was, you know, how different understandings about time are at the crux of the confrontation between African peoples and Europeans. And what does it mean to face clock time and calendars with harvest time and moon time and just different kinds of attention to how we use time?

CB: And the different rhythms that stem from the different understandings of time too, right?

LW: Where many people are from, you would never labor in the middle of the hot sun. That wouldn’t make sense.

You could take a nap in the middle of the day, [when the sun is hottest], and it wasn’t about being lazy, right? It’s an actual good use of your time to rest at this point of the day. So you know we’re always operating with these many times confronting one another.

So I think the show was asking this question of not only retreat, but how do we use [and relate to] time, how do we explain our time to people? How is that challenge of being able to communicate time also where a lot of the friction in our lives comes from?

Part of it was also the irony that the pace of producing that show meant that the people who were working on it were, super busy, the whole time. And something I thought about a lot after this time was that I wish that I had found ways to model the actual ideas of the show, like the teaching of the class and the space that we were making but that didn’t happen so much.

[One moment when we did model the ideas of the show was when] we invited Tricia Hersey from The Nap Ministry to come. We had a nap in the museum. We laid out in the galleries and, you know, it was, it was really special. We had a conversation with [theologian and spiritual care practitioner] Mati Engel and talked about themes of rest, repair, and healing.

CB: Another thing I wanted to ask you about is actually connected to something you’ve already sort of mentioned: The Black feminist principle of bridging theory to praxis. Did curating this show also spur a kind of reconsideration of the pace at which you teach or even the pace at which you enact your life in excess of your work responsibilities at the Art Institute?

LW: It really should have. I think about it a lot. I want to find more ways to get there. I think it’s like a constant fight with oneself about like, you know when you get excited about different projects. Like I’m trying to say, ‘”yes” less. Or it’s like a “no” for now and maybe a “yes” later.

I sometimes find that [saying no] makes me feel off somehow. I’m like, I should be doing more stuff. Like what have I done with my day and time?

But then the flip of it is that if you’re not modeling it in your world, it’s like you can say as much as you want about different ideas, but what does it really mean? So it’s a work in progress, but on my mind a lot.

CB: The exhibition made me think about a book I read called “Cruising Utopia” by Jose Esteban Munoz. He has a whole chapter about aesthetics and he talks about how art can serve as a catalyst for contemplation. And that contemplation can galvanize those who encounter certain art objects to start participating in the critique of the systems that kind of reign over their lives and structure the ways they think about time and all of these other things that we’ve discussed so far.

But I remember reading that and feeling a really large degree of resistance to accepting that idea point blank. It felt incomplete to me because it brought up the question of who has time to contemplate? Who has time to come to the Smart Museum and be nourished enough in all the ways they need to really be open to the exhibition’s capacity to provide space for that critique?

And I wonder if you guys thought about that explicitly in class and kind of what the sum of those conversations was.

LW: Who has time for museums? That’s a big one. Through our inquiry, we wondered if the art needed to move outside of the building itself or if it needed to find other ways to connect with people in spaces. It’s not something that we realized through our projects. But it does make me think about something like Toward Common Cause.

There were some Njideka Akulini Crosby works on the side of the National Public Housing Museum, which got me thinking about the way artworks can enter spaces and be something that just becomes a part of your sightline. It’s something that raises or lifts or becomes the site of potential.

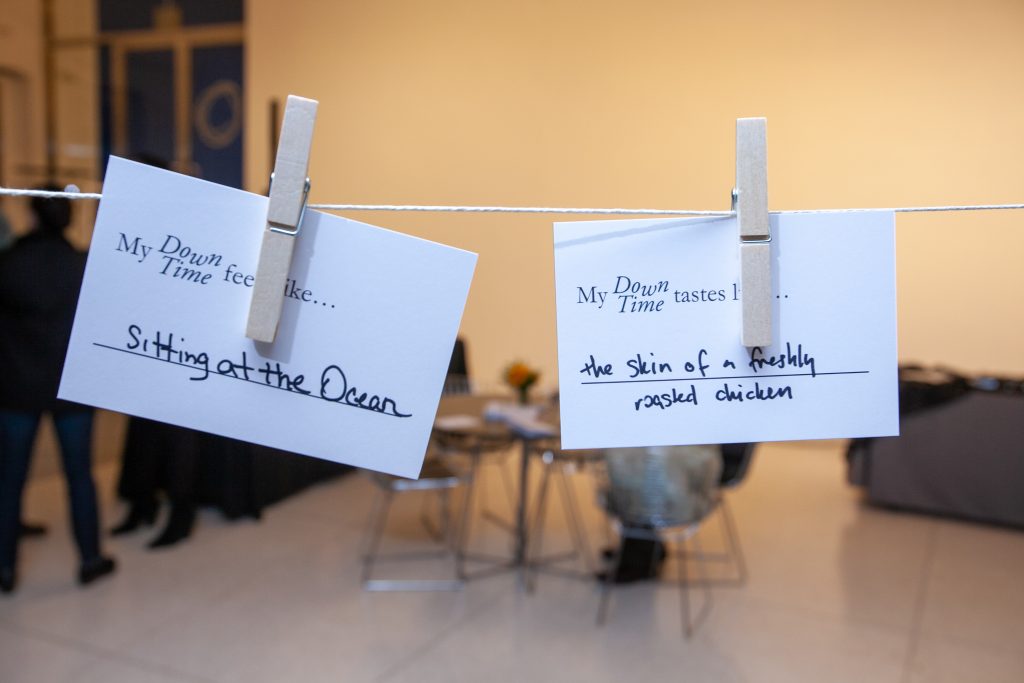

One student, Aneesah Ettress, suggested something that we brought into the show, which were these cards that said “My downtime smells like… my downtime feels like… my downtime looks like…” We went through all these different sensory zones to try to get at the ways in which we might be accessing that in some other way. And you know, for me, it was like my downtime tastes like risotto because it means I’ve had enough time that day to actually make risotto.

But there is a way in which we were asking is the museum a luxury? But then it’s also what are the ways in which museums are third spaces? Especially a space like the Smart that is free and open to all. So like, you know, that lobby is a space where you can sit and spend time and you don’t have to look at the art. You can be in the space that the museum affords you. And I think there’s real value in making that available to communities and really announcing that.

But I think this is one of the real pernicious questions of the show and it was why, you know, we looked at some thought exercises in class together. [Like this one]: A Black man is walking along Lakeshore path on the South Side at night and maybe gets stopped by someone in the police department who asks what he’s up to. What if his response is that he’s out to look at stars? What if his response is that it’s a really good night for stars? Do we think he’s believed? Like is that man up to something?

CB: Almost like that sort of contemplation and “downtime” is not a legible thing for Black people to be doing unless it’s somehow tied to some other “suspicious” activity.

LW: One of the anecdotes that I’ve told in relation to this show that made me think about a lot is that my dad, since retired from the military, is really into nature. He does a lot of nature photography. He will pull his car over the side of the road, you know, in a zone that may not look like the most picturesque, but because he sees a cluster of flowers that he thinks are really beautiful. He will do it because he’s moved by it.

Actually, someone once yelled out of their car, “Get a job!” My father is retired. He is someone who’s just out with a camera photographing trees and that’s read as a sign that he is like—

CB: Idle, Or, like, listless or whatever.

LW: Especially you know, in the height of the pandemic, pre-vaccine, and someone in his early 70 years, he was out with his camera in his neighborhood. People were like “What’s this dude up to?” And he’s like “dragonflies.”

He’s living in Florida. There are lizards there. You know, there’s all this stuff that’s right around him. And it’s nice to just walk around the neighborhood and look at these things.

But, what does it mean to still do those things as a Black person?

CB: As we touched on a bit earlier, you created this exhibition in collaboration with graduate students and undergraduate students. Something that often frustrates me is this idea of singular genius that plagues our field so deeply. I regard your willingness to collaborate with students as a challenge to that idea of singular genius and a gesture of renegotiating power. You ceded power and you ceded authority in this very specific way. And I wonder what that felt like?

LW: I love working collaboratively. So that’s something that I’ve wrestled with in my life as a professor. Like I can go off in a corner and work on this thing and I still love writing things independently. But I like kicking ideas around, so that felt really natural. By the time we were done with this project, we had a total of 28 students who had contributed to it in some way, shape, or form. They’d all written labels for the show and so like multiple vocality was what we were working with. So that is a lot. But it’s so much richer for all of those ideas. It never would have been the thing that it was without having all of that in that space and testing things out.

And you still might have under-considered something, right? And so I think there’s a real privilege to this project and giving us space to really explore but know that we can’t do everything. And I think it is something that channels through and flows through my other projects. I learned a lot about how to do that. [It taught me] to be sensitive in another kind of way.

I don’t want to produce harm in this space. I want students to feel listened to and that there are times when we can do that better. And I think there was a real mix of that for me across the project.

CB: I have one more question for you, and it kind of also returns back to what you said at the beginning. I was so moved by the question of how can “getting away” shape an ultimate return. And it reminded me so much of something another curator Legacy Russell, who is the director of The Kitchen in New York, has said. She once talked about how she – like I imagine you are as well – is really committed to seeding institutional change and how she had to leave institutions for a bit in order to really understand her adoration for and commitment to them. And I wonder if you, since the show closed, have had time to think about that question for yourself? What about your ultimate return?

LW: Yes, yes. That is a great yes. It is something I was really in the weeds and wrestling with.

I had a student recently say it seems like the pace of change in museums is slow, but the pace of change at universities is also slow. And so we’re like, which is better?

It’s a great question because we’re trying to find spaces to go, but institutions are hard–every single last one. We’re always challenged by institutions. And so if we’re not moving to the woods, how are we showing up.

I find myself thinking a lot about Yesomi Umolu’s, 14 points. It is absolutely critical that museums change their practices, engage with really challenging histories and really get to know how they got what they have, how they’ve talked about what they have.

But also these spaces need us. And if we’re honest with ourselves, we love them. And we love art and we care about this. And, you know, it’s like, what if that isn’t a contradiction? Or what if that isn’t something that has to be a site of fundamental ambivalence? What if that is a space from which to work? So what now? How do we face down the truth?

There’s less despair behind the door of that question.

About the Author: Camille Bacon is a Chicago-based writer who is cultivating a “sweet Black writing life” as informed by the words of poet Nikky Finney and the infinite wisdom of the Black feminist tradition more broadly. Her curiosities orbit around the aesthetic legacy of Black abstraction and the cultural production of her two homes: the United States and Martinique. She is a graduate of Smith College, has interned at The Studio Museum in Harlem, and has participated in writing programs such as The Black Embodiments Studio and the Momus Emerging Critics Residency.