Featured image: Full installation view of Fazal Sheikh’s piece, Desert Bloom, on display at Toward Common Cause: Art, Social Change, and the MacArthur Fellows Program at 40 at Hyde Park Art Center. The piece contains 48 inkjet prints of aerial photographs that were taken in 2011. Image courtesy of Hyde Park Art Center.

Artists at Hyde Park Art Center are turning their talents to expose and scrutinize the toll of environmental racism and the effects it has on people of color, from the streets of Flint to plots of the Middle Eastern desert.

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Mel Chin, and Fazal Sheikh are participating in Hyde Park Art Center’s exhibit “Toward Common Cause: Art, Social Change, and the MacArthur Fellows Program at 40,” a city-wide exhibition that started in the summer of 2021 and will run at various lengths through 2022. The Hyde Park iteration closed on October 24, 2021.

Toward Common Cause is a collaboration between more than two dozen exhibitions, programmatic, and research partner organizations across Chicago. It was organized by the Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago. As part of the 40th anniversary of the MacArthur Fellows Program, it features new and recontextualized works by 29 visual artists who have been named Fellows since the program was founded in 1981.

One of the things that the city-wide exhibition explores is the role that art plays in bearing witness and potentially being an act of resistance. It casts a light on the extent to which certain resources (e.g., air, land, water, culture) can be held in common and what happens when some people are excluded from or denied rights of access to these resources.

The three artists at the Hyde Park Art Center focus on environmental racism and inequalities. What happens when an entire city of mostly economically disadvantaged people are exposed to industrial pollution such as lead poisoning? What happens when we restrict access to healthcare, food, and clean water? What happens when we take land away from people and destroy the places in which they live?

In 2016, LaToya Ruby Frazier headed to Flint, Michigan to cover the water crisis—a human-made disaster created when the state-appointed emergency manager changed water supply as a money-saving move and failed to apply corrosion inhibitors to the pipes, releasing lead into the drinking water and poisoning the entire city.

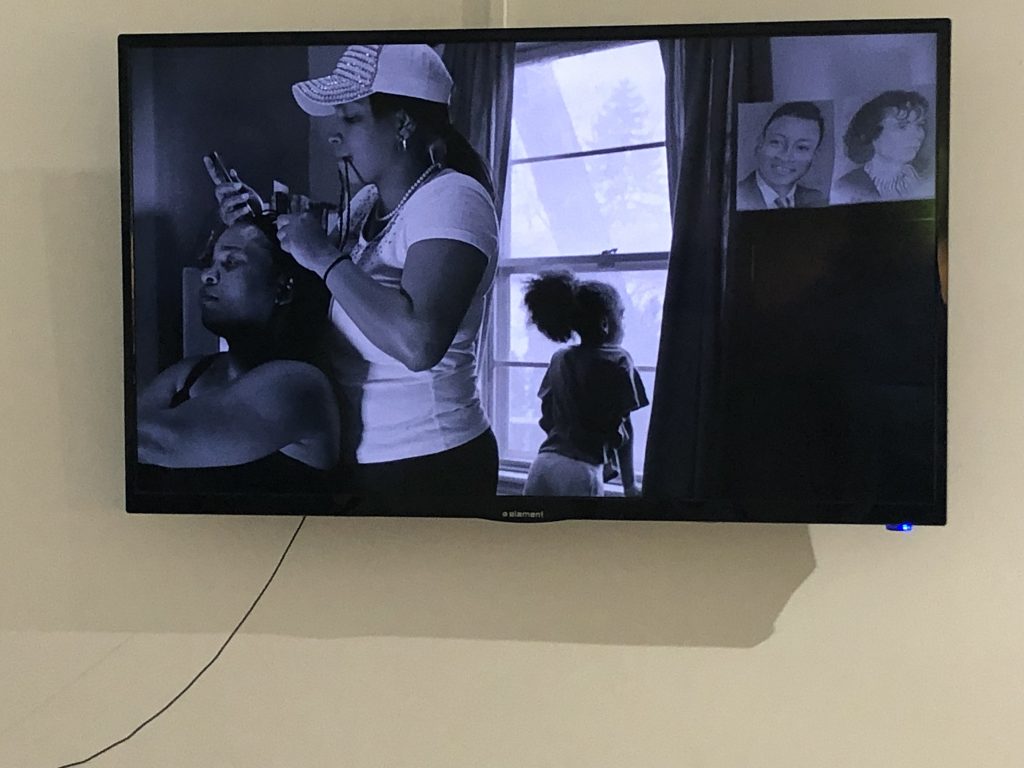

Frazier’s is the first work that guests see upon entering the exhibition. A video screen portrays a slideshow of the black and white photos she took during her five-month stay in Flint. Some pictures are what might be expected: photos of large, collective protests and ominous warning signs about lead poisoning. Others are more intimate pictures that depict families who live in the city, opening a window into their everyday lives.

Frazier’s work is humanizing, not just portraying the cost with statistics or explanations of the effects of lead poisoning, but also with highly personal visual narratives of individuals. Her work stresses that Flint is a city of Black people, and that the water crisis was ultimately an act of environmental racism—from the taking away of rights to representation from the residents with the installation of an emergency manager, to the slow response and stonewalling of those who raised the alarm that there was something wrong with the water.

Paired with Frazier’s photos is a voice-over to the video that was prepared by Shea Cobb, a lifelong Flint resident who shares her lived experiences in the city.

Frazier’s book on this project, Flint is Family in Three Acts, won the inaugural award of the Gordon Parks Foundation/Steidl Book Prize.

In 2008, Mel Chin began a project that he had hoped would fill a short-term need. Instead, over the past 13 years, the need for it has continued to grow and became more intense.

Chin’s Fundred Project aims to shine a light on lead contamination and its effect on children. It began after Hurricane Katrina, an event that made the already bad prevalence of lead poisoning even worse. Throughout the years, he’s expanded the program from New Orleans to help such places as Chicago, Flint, and Cleveland.

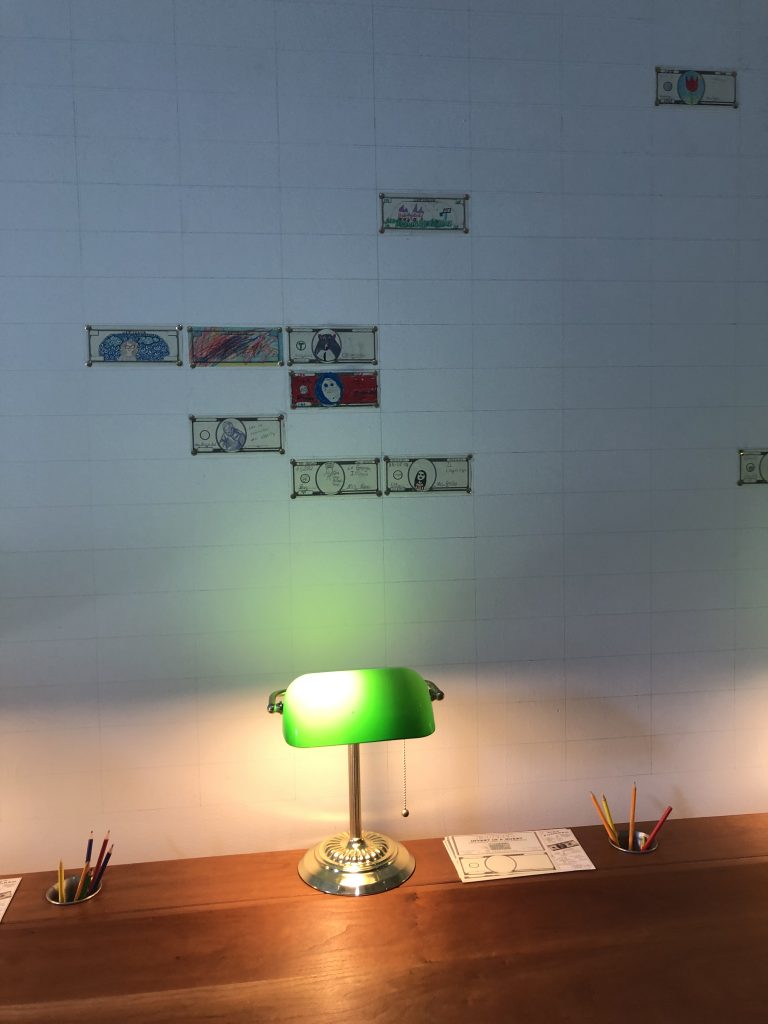

The Fundred Project consists of hundreds of thousands of drawings created not by Chin, but by children from around the world. He created the idea of a “Fundred” dollar bill on which children would color, draw, or paint. The children who are most affected by lead poisoning create the currency and their voices cry out through the art they make. The artist then collects and exhibits them in places where lawmakers could be influenced to make a difference.

As part of the Toward Common Cause project, Chin has created two places where children can do their part to not just raise awareness, but to demand an end to lead exposure. He has tables and art supplies spread out at Hyde Park Art Center and Sweet Water Foundation. The Fundreds that are created in these two locations will make up the Chicago Fundred Reserve, a pile of bills that presents a striking visual comparison to the historic disinvestment that communities of color experience across the city.

The Hyde Park Art Center Fundred program also includes three supporting videos:

Capital to Capitol: The Story of Fundred, a documentary of the Fundred project from 2008 to 2020, directed by Ben Premeaux.

Now You See It, two animated shorts that explain the threat of lead poisoning. The shorts show how lead contamination works and why it is so dangerous. It is directed by Chin and produced in partnership with LA Freewaves, Fundred Project, with animator Careen Ingle, sound artist Zig Gron, Southern California Health & Housing Council and the Healthy Homes Collaborative.

Do you wanna make a Fundred?, a short instructional video explaining how to make a Fundred. It is produced by S.O.U.R.C.E. Studio with artists Maps Glover and Fabiola R. Delgado, animator Thom Solo, sound editing by Public Media Institute, and with voiceovers by Issa and Aya Williams.

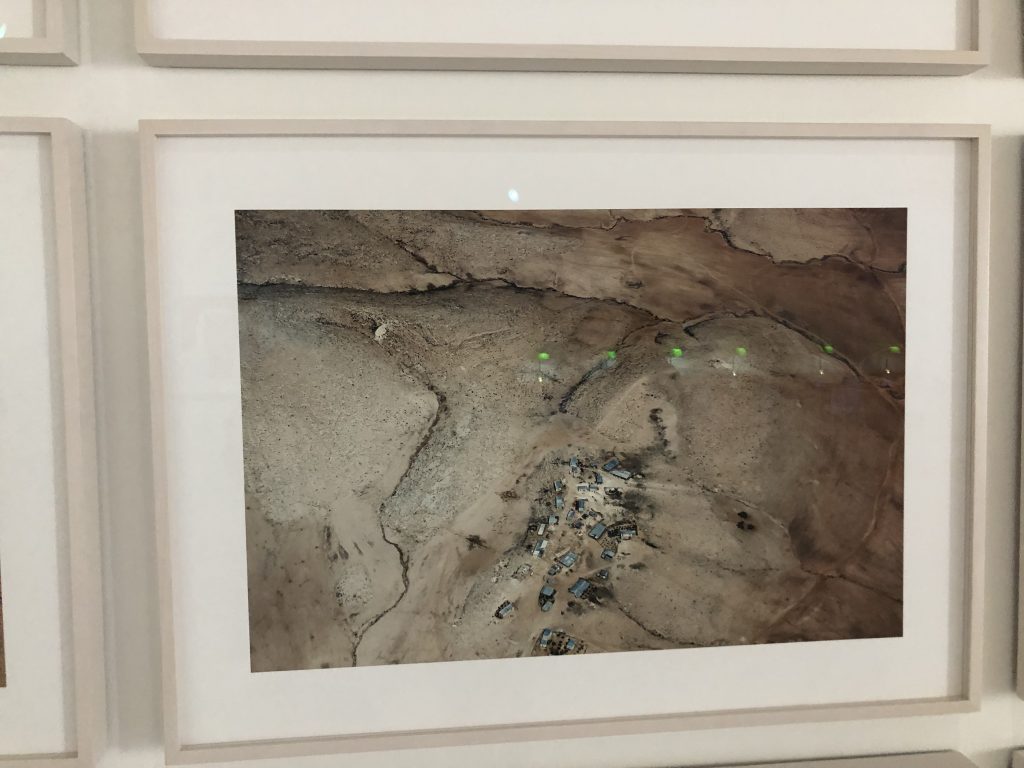

Fazal Sheikh’s Desert Bloom series, part of a larger work called Erasure Trilogy, takes up the largest part of the exhibition space. It is a complex spread of photographs showing how Bedouin communities have been displaced in Israel’s Negev desert. The title comes from the first Prime Minister of Israel David Ben-Gurion’s dream of settling the Negev and making the “desert bloom”.

The piece contains 48 inkjet prints of aerial photographs that were taken in 2011. The back wall of the Hyde Park Art Center exhibition space is covered with these photos; lonely, stark images that require interpretation and explanation.

Sheikh worked with architect Eyal Weizman to record information about the connection between the displacement of Bedouin communities from the Negev desert and desertification, colonialism, afforestation, the creation of mining projects, military training camps, and the clearing and appropriation of the desert. The pictures pay careful witness to how each of these spots in the desert have been treated. Sheikh worked with Eyal Weizman to further document the events, together gathering additional data including remote sensing data, remote plans, court testimonies, land contracts, maps, and 19th century traveler accounts.

There is special attention paid to Al-‘Araqib, a village that has been destroyed and rebuilt more than 188 times between July 2010 and June 1, 2021. Sheikh created a video that captures the history of the village and the Israeli state’s efforts to displace the Palestinian Bedouins who have lived there. Pictures show the fenced-in ancestral cemetery in 2011 where family members retreated.

Other pictures were taken in 2014, the year the Israeli Land Authority was joined by the Special Forces and the Jewish National Fund to demolish all remaining dwellings within the cemetery except for the gravestones and a tent used as a mosque.

The documentation can almost be overwhelming—photos taken from a distance that demand special knowledge to fully understand. The accompanying placards—written in English, Hebrew, and Arabic—act as more of a tease, a window into a story that is only partially told by these photos. They warn against an erasure; many of the images show what has been removed rather than what was present.

Together, the three works challenge a move toward change and tell stories of the ways that the lives of people of color have been threatened through neglect and targeted violence. These artists document events from all around the world and search for ways that their works can draw attention to injustices and perhaps create change.

It is a challenging exhibit—the works aren’t pretty. Rather, they ask a compelling question: Now that you know, what are you going to do?

Bridgette M. Redman is a Michigan-based journalist who writes about the arts for publications in Lansing, Detroit, Phoenix, Tucson, Los Angeles, Santa Monica and Houston. A member of the National Theatre Critics Association, her theater writing appears in several national publications. She is a second-generation journalist who believes in the power of art and writing to change our communities for the better.