The Chicago Archives + Artists Project (CA+AP) is an initiative that highlights Chicago archives and special collections that give space to voices on the margins of history. Led by Chicago-based writers and artists, the project explores archives across the city via online features, a series of public programs and new commissioned artwork by Chicago artists. For 2018, the Gaylord and Dorothy Donnelley Foundation has funded a series of pilot projects pairing three artists with three archives around the city: Media Burn + Ivan LOZANO, the Leather Archives & Museum + Aay Preston-Myint, and the Newberry Library’s Chicago Protest Collection + H. Melt. This series of articles will profile these featured archives and artists over the course of their collaboration, exploring the vital role of the archive in preserving and interpreting the stories of our city as well as the ways in which they can be a resource for creatives in the community.

Join us on December 1, 2018 from 6-9 pm at the Leather Archives & Museum for Artists + Archives: Pilots, which will exhibit the commissioned projects by each artist alongside the archive materials that inspired them, launching CA+AP’s first year-long collaboration between artists and archives across the city.

For this installment, I corresponded with writer and artist H. Melt about documenting the trans community, their artistic practice, and their experience exploring the Newberry Library’s Chicago Protest Collection to create new pieces for this project. You can find their recently published book of poetry, “On My Way to Liberation,” here.

Jennifer Patiño Cervantes: To start at the beginning, what made you want to be an artist and writer? How would you describe your work?

H. Melt: My work is a celebration of queer and trans communities. I’m a poet and visual artist, a teacher, and cultural organizer. I’ve been interested in art since a young age. There’s a great picture of me dressed up for Halloween as my childhood version of an artist. I’m holding a palette filled with different colors of paint. I didn’t envision a career in writing until much later, around the age of twenty. Making art brings me joy. I learn a lot about myself through artmaking and writing. It’s the place where I am most honest with myself, and can most clearly assert my trans identity.

JPC: You’ve mentioned previously in bios that your poetry documents Chicago’s queer and trans communities. As a poet and as an artist, as an editor of an anthology, do you view any similarities between the work of an archivist and your practice?

HM: Archive building is definitely part of my practice. I edited a zine called “Second to None: Queer & Trans Chicago Voices” that led to my job at Women & Children First [a bookstore in Chicago]. I view my first book, “The Plural, The Blurring,” as an archive, not just of my community, but of myself. Editing the anthology “Subject to Change” was a way to collect conversations I was having with trans poets and get more trans poets into libraries. I have a very direct personal connection to the work that I archive. I’m part of the communities I’m archiving.

HM: One difference is that my work involves much less formality and is more accessible than a traditional archive. Most archives aren’t digitized, you have to visit them in person, make an appointment, be approved to do research. You can’t walk in and browse. Someone else has to grant you access. I work hard to make my writing and art available to queer and trans people. I show art in community spaces, give away prints for free or sell them very cheaply, collaborate with bookstores who support queer writers, publish poetry online and in print. I think many archives fail to engage with the communities their collections represent. What’s the point of having an archive if people can’t access it?

I worked in a library for a few years at the Poetry Foundation. I mostly led youth educational programs and occasionally worked the library desk. One of my goals there was to encourage the acquisition of more books by queer and trans poets. I shared a desk and computer with a cataloging intern. There was always a cart full of material waiting to be processed next to me. I asked to be trained in cataloging and my boss said no. I asked for funding to attend library school and was denied. I love libraries, but this is the type of gatekeeping that has made it difficult for me to have a career in the field. This is why I love smaller community archives like Read/Write Library and the Queer Zine Archive Project.

JPC: For this project, you’ve been working with the Newberry Library’s Chicago Protest Collection. Have you worked with other archives before in your practice or is this a new experience?

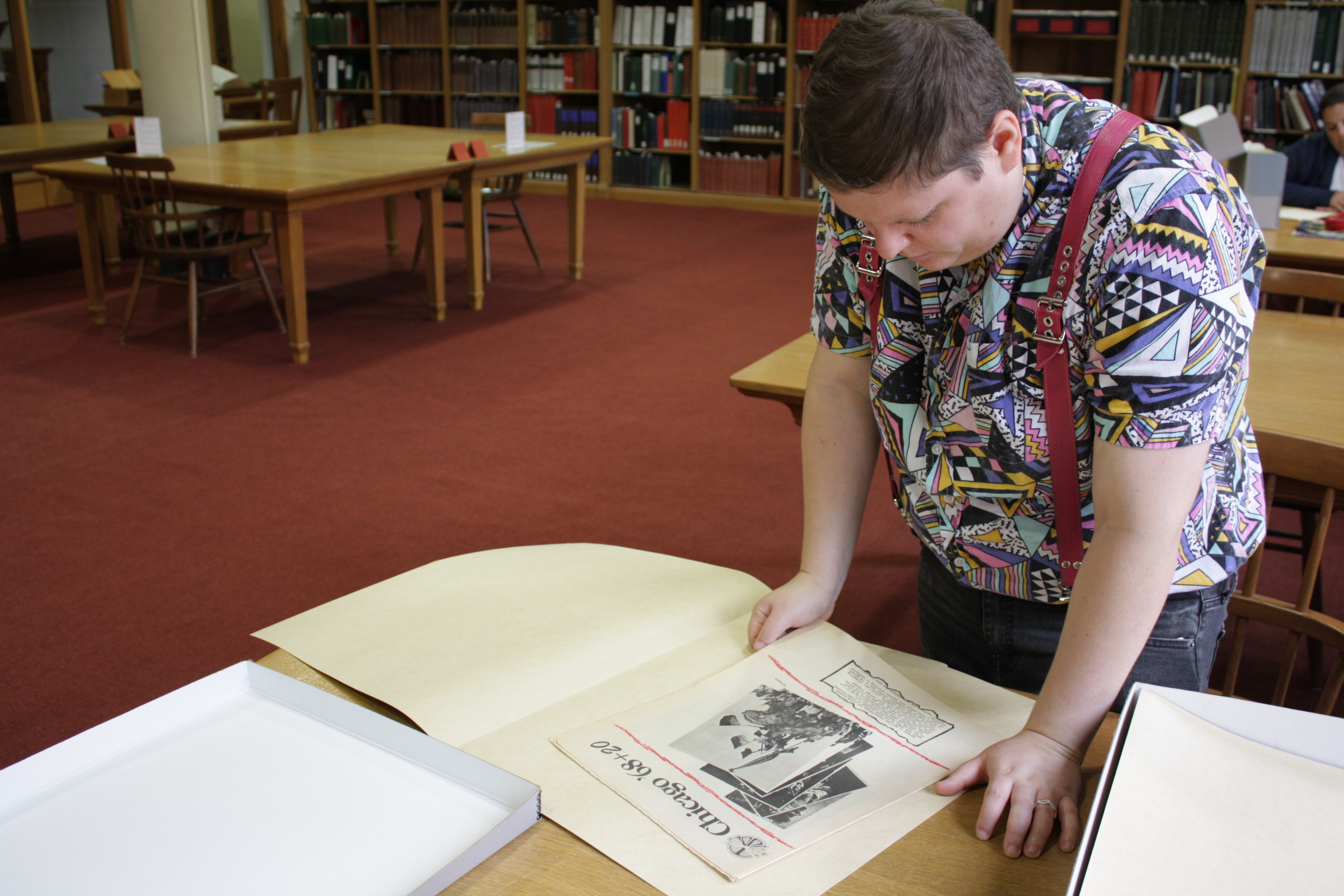

HM: It’s a new experience! I’ve always wanted to work with archives but didn’t have an entry point. Sixty Inches from Center has provided access that I wouldn’t have pursued on my own. I’m grateful for that. One really valuable part of working with the archive is understanding how to preserve materials, and what types of things might be interesting or useful to people in the future. I’ve also learned a lot about the decision-making power of archivists.

JPC: What has the experience of working with these particular archives been like? What have you found yourself exploring? What has the trajectory of your research been like?

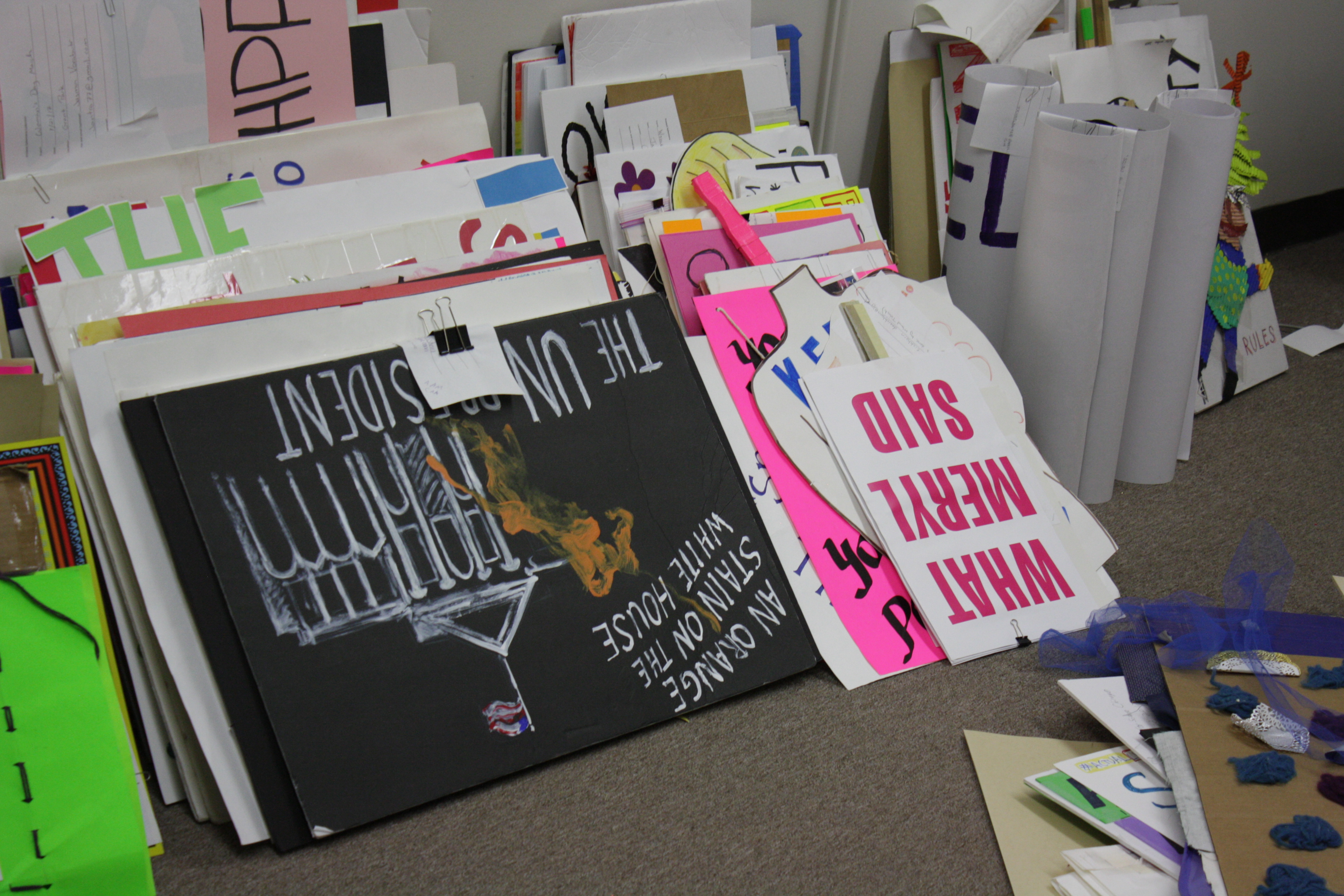

HM: I’ve mostly focused on the history of protest in Chicago. I started with the unprocessed Chicago Protest Collection, which features signs from the Women’s March, the March for Science, and a small collection of materials from the Muslim ban protests at O’Hare. I looked at hundreds of signs: how they were constructed, what materials were used, hand-lettering styles, colors, and reoccurring slogans. I then moved into the special collections room at the Newberry and viewed a range of other materials including their Black Lives Matter collection, newspapers from Students for a Democratic Society, a map of “gay Chicago,” a pamphlet from the first Lesbian Writers Conference in Chicago, Melvin Dixon’s file with Tia Chucha Press, and photos Chuck Renslow took of his partner Etienne, who was a dancer and had his own dance company. To my slight disappointment, they were all promotional photos of his dance career.

JPC: Have you had any surprises while working in the archives? What have been the benefits or challenges you’ve encountered?

HM: One of the biggest surprises was finding work by people I know in the archives! I identified several items made by artists I know, including photographs taken by Sarah-Ji of Love+Struggle Photos and posters by Pansy Guild. The biggest struggle was finding trans materials. I pretty much gave up on trying to find anything trans in special collections via the Newberry’s database. The place where I found the most trans material was in the Black Lives Matter collection. There were a few items related to gay and lesbian history, but I was disappointed at how little queer history I found at the Newberry, considering the massive size of their archives. I was hoping for more.

JPC: One of the themes that I have noticed come up in your poetry is the problem of misnaming and misgendering. Thinking about the use of names in cataloging and archives, is that something that you’ve had to navigate during this project?

HM: It’s a problem within queer and trans history more broadly. People are hesitant to label historical materials as queer or trans because people wouldn’t have self-identified that way, which is understandable. However, I think there is a way to categorize items so people in the present and future can find them. Using a term like “gender identity” for example is a way to mark something without labeling someone or harming future researchers. I found so many outdated terms in the catalog. There should be more of an effort to educate and hire librarians and archivists from marginalized communities. There’s so much erasure that happens in archives. The Joan Flasch Artists’ Book Collection improperly labeled a chapbook I wrote as “lesbian,” even though the subtitle of the book on the cover uses the word “transqueer.” That’s the same logic, ignoring how people self-identify, that leads to discrimination and violence in my everyday life.

JPC: During Sixty’s Chicago Archives + Artists Festival, you contributed a file to the Chicago Artists Files. How did you choose the items you submitted for your Chicago Artists File? Did you find yourself influenced in your choices by your work with the Chicago Protest Collection?

HM: I tried to choose the materials that were most important to me, that make me feel proud. I included things that spanned from throughout my career and highlighted different aspects of it, from early zines I’ve made to business cards for jobs I’ve worked, programs for workshops I’ve participated in, posters for performances I’ve done, an award I received. I chose things that I think are visually interesting and provide context for my work, that show the people and places that support and care about me.

JPC: What has been your favorite piece of ephemera that you’ve come across so far while exploring in the archives?

HM: It’s hard to choose just one! The protest signs that affected me the most were the ones scribbled on yellow legal paper asking questions like “are you okay?” “do you need help?” and “do you need an attorney?” from the protests at O’Hare. I participated in those protests and something about their practicality, urgency, and simplicity struck me. I found the map of “gay Chicago” interesting, which was really just a map of gay bars on the North Side. So many of the places aren’t open anymore, and it illustrates the whiteness and bias of the publication that produced the map. There was a great zine called Black Trans Lives Matter written by Jaz that was very critical of capitalism and gay nonprofits, which I loved. I also spotted a vintage ad from the late 80s for Chicago Women’s Health Center with the title “Women helping women.” I’m glad how much their services have expanded since then. Lastly, I appreciated seeing the very brief letters between Tia Chucha Press and Melvin Dixon’s estate about posthumously publishing his book, “Love’s Instruments.” There’s still so much more material I want to explore. I would love to work with other archives in the future.

JPC: Can you tell us about the piece you are creating through this project? What form will it take, and how has your research in the archives influenced it?

HM: I’ve been working on several new pieces for this project. I’ve made a few fabric banners with trans-affirming language and symbols on them. These include phrases and words like “Trans for Trans,” “THEY,” and “Mx.” I went a little out of my comfort zone and made a trans cape, envisioning what the logo for a trans superhero would look like. I’m also collaborating with Pansy Guild to create a poster version of the “Trans for Trans” piece.

JPC: Do you keep a personal archive? Do you feel that this project has had an impact on the way you think about preserving your own work?

HM: I primarily collect queer and trans literature and art, with a Chicago focus. This includes books, zines, catalogs, posters, buttons, and more. I think everyone builds their own archive throughout their lives. People are living archives. Everyone has stories that are meaningful and deserving of preservation. I have photos of my life, postcards and tickets for events I’ve attended, books that reflect my interests. I try to hold onto items relevant to my own artistic development. I think the best place I archive myself is through my writing. That’s what I hope lasts the longest, captures who I am, and provides understanding to people in the future. This project reminded me that queer and trans people must build their own archives and preserve their own histories, because they’re not likely to be found in institutions outside of our own communities.

The Chicago Archives + Artists Project (CA+AP) is part of Art Design Chicago, an initiative of the Terra Foundation for American Art exploring Chicago’s art and design legacy, with presenting partner The Richard H. Driehaus Foundation. The project is funded by the Terra Foundation for American Art and The Richard H. Driehaus Foundation.

Featured image: H. Melt is seated in their room facing the camera. They are wearing a plaid button-up shirt and red suspenders. Behind them is a blue, white, and pink transgender pride flag with the words “I am alive” written across it in purple capital letters. Photo by Ally Almore.

Jennifer Patiño Cervantes grew up on the Southwest Side of Chicago with roots in Mexico. She is a freelance writer, poet, essayist, and Director of Operations + Archives for Sixty Inches From Center. She graduated from Columbia College with a degree in Art History and double minors in Poetry and Latino/Hispanic Studies. She is currently pursuing her MLIS at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Jennifer Patiño Cervantes grew up on the Southwest Side of Chicago with roots in Mexico. She is a freelance writer, poet, essayist, and Director of Operations + Archives for Sixty Inches From Center. She graduated from Columbia College with a degree in Art History and double minors in Poetry and Latino/Hispanic Studies. She is currently pursuing her MLIS at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.