“Often by chance, via out-of-the-way card catalogues, or through previous web surfing, a particular ‘deep’ text, or a simple object (bobbin, sampler, scrap of lace) reveals itself here at the surface of the visible, by mystic documentary telepathy. Quickly — precariously — coming as it does from an opposite direction. If you are lucky, you may experience a moment before.”

— Susan Howe, “The Telepathy of Archives”

This past February, an initiative to pull books containing “LGBTQ content” from a public library swept through Orange City, Iowa. While the campaign wasn’t successful, its intentions remain the stuff of relatively recent Midwestern history. This is to say that when the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives was founded in 1981, patrons couldn’t necessarily count on finding their own experiences and narratives reflected in the shelves of public libraries — while queer content might not have been explicitly banned, it was certainly a blind spot in most mainstream collections.

Named after Henry Gerber (founder of the first American gay rights association incorporated in Illinois) and Pearl Hart (one of Chicago’s first female attorneys and most progressive public defenders), the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives is an absolutely crucial resource for anyone who wishes to better understand LGBTQ+ history and the people who constitute it. After years of frequent moves, the collection has found a welcoming home on Clark Street in Rogers Park, on the second floor of an expansive new building which also serves as a Howard Brown Health Center. It is beloved by the broader Chicagoland community for plenty of reasons — its yearly book sale, weekly game night, and regular film programming, to name a few. Gerber/Hart’s co-habitation with Howard Brown has also lead to a satellite exhibition space in the clinic’s lobby, and another exhibition space on the second floor features a curated array of holdings from the special collections.

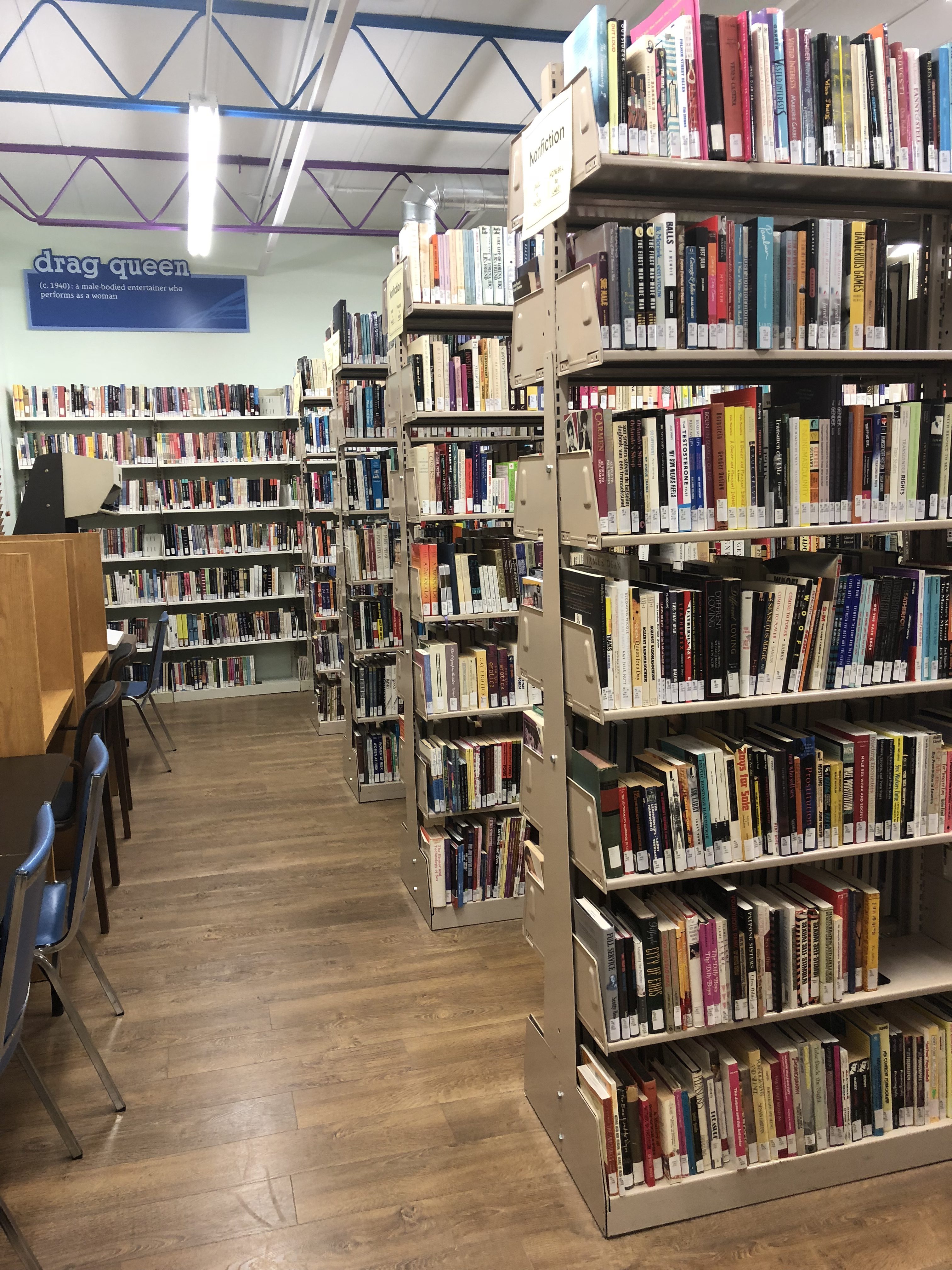

Walk past all of these displays, though, and you’ll reach the three modestly-sized rooms that house the largest circulating queer library in the Midwest. Encompassing everything from academic and clinical texts to fiction and poetry, Gerber/Hart’s collections chart a history of changing names, attitudes, and prerogatives surrounding sexuality and gender identity. As a queer person navigating this collection, I came to appreciate just how much of my self-understanding was placed on top of this archival scaffolding. Decades of re-defining and reclaiming one’s terms, of historically contingent genders and sexualities, have fed into the myriad definitions and conventions we have in place today. This may seem self-evident to most readers, but physically confronting those texts in an institution like Gerber/Hart remains a welcome reminder. What’s more, many of these volumes are extremely difficult to find elsewhere — often they have been out of print for decades.

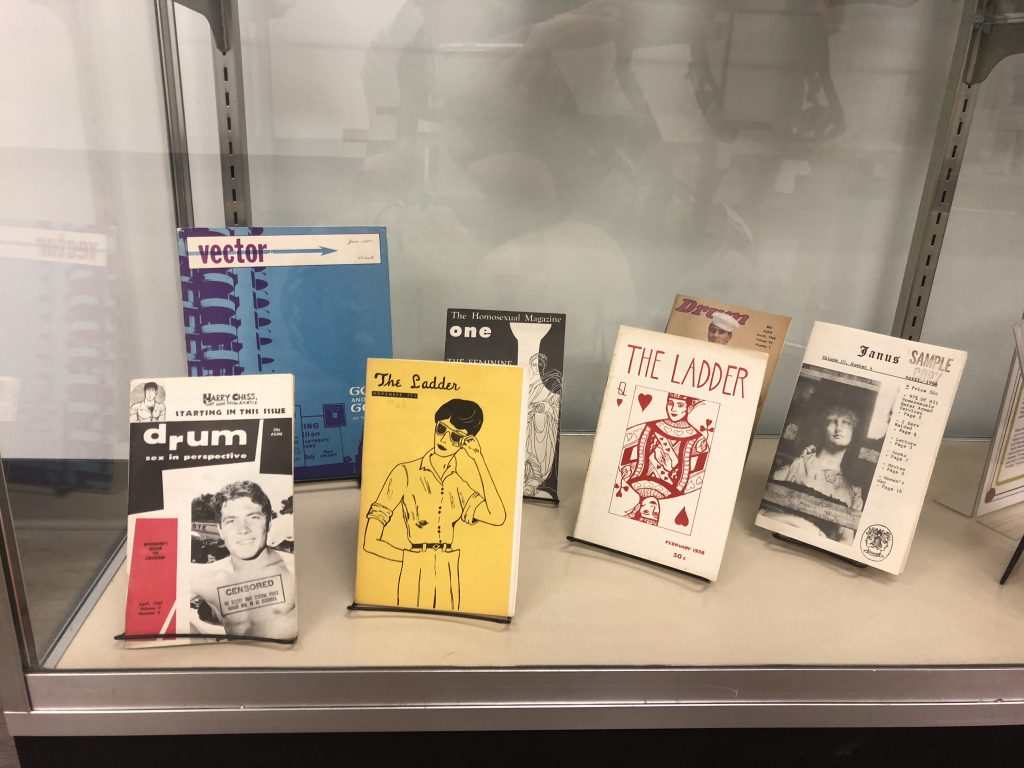

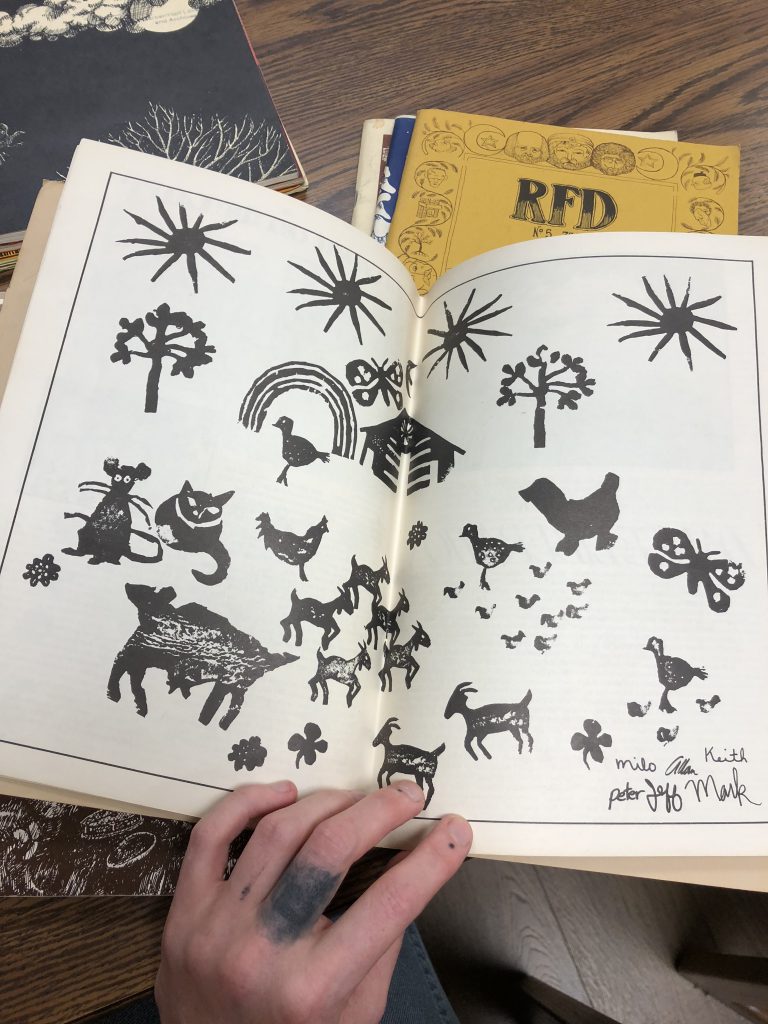

Such rarity, though, is nothing compared to the holdings in Gerber/Hart’s Special Collections. Composed of over 150 separate collections from both individuals and organizations, these materials allow a present-day researcher to actually “experience a moment before”, as Howe might have put it. Perusing the archives is much more involved than looking through the circulating collection, especially if one does not exactly know what to look for — many of the collections are unprocessed and more still lack specific finding aids, though the library has several initiatives in place to improve the accessibility of its materials. Amidst the personal effects and correspondence of notable Midwestern LGBTQ+ activists, one can also find posters, board games, and erotica from the 1930s — when efforts to dodge obscenity laws led to cleverly placed scratch-off undergarments.

In his article on queer archival research, historian Tim Retzloff notes the importance of “fugitive” material in LGBTQ+ studies — that is, material that remains in the possession of individuals rather than being incorporated into an institutional collection. Indeed, some of the periodicals I looked at during my time at Gerber/Hart were part of incomplete collections — because they were donated by an individual rather than safeguarded by a broader organization, and the person in question just didn’t happen to have all the back issues. The same is almost always true for archival records and ephemera. Threads are left out, lost, hidden, to be picked back up decades later. Rather than being a hurdle to research, though, these fugitive materials and their possible omissions are simply what we have to constitute such histories. This makes queer archiving a practice whose materials often exist in a fraught relationship to public institutional collections. This is to say that we can handle these materials today because someone took care of them despite efforts to erase their narratives from historical record. Such is the value of archives more generally: how many of those “moments before” have we simply not been allowed to think about on their own terms?

For artists, still another facet of archival research is valuable: the tactility of print artifacts and the ability to actually hold materials and engage with them as primary sources rather than digitized objects. Digitized collections are, indeed, quite important for further disseminating these documents and circulating them to a broader public. But in taking the necessary steps to actually handle and page through magazines from decades before I was born, my experience of that “moment before” was eminently more profound. Scanning the shelves of travel guides and reader-produced quarterlies, I came to appreciate the care and attention involved in carving out safe spaces for queer content in the pre-internet Midwest. Thankfully, Chicago has the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives to continue holding this sort of space, with commitment to our shared history, and more still to come.

Featured Image: The stacks of the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives. Closest to the viewer are the nonfiction volumes, with fiction held on the shelves further away. A few study booths are placed by the window to the left, and a banner above the shelves reads, “drag queen (c. 1940): a male-bodied entertainer who performs as a woman”. Photo by Maddie Kodat.

Maddie Kodat is a movement artist and writer working between Chicago and New York City. Maddie has performed with Ginger Krebs, Ballez, LA Warman, La Casa de Satanas, and Amelie Jakobsen; they have also published work with WINDOW, Glass Press of the Future, and Meekling Press. Maddie received a BFA in Studio Art and a BA in Visual/Critical Studies from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2017, prior to which they danced as a company member with Ballet Chicago for five years.

Maddie Kodat is a movement artist and writer working between Chicago and New York City. Maddie has performed with Ginger Krebs, Ballez, LA Warman, La Casa de Satanas, and Amelie Jakobsen; they have also published work with WINDOW, Glass Press of the Future, and Meekling Press. Maddie received a BFA in Studio Art and a BA in Visual/Critical Studies from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2017, prior to which they danced as a company member with Ballet Chicago for five years.