Libyans sometimes refer to being arrested and taken away without warning as being “taken behind the sun.” This interview series celebrates—through conversations with formerly-incarcerated artists and their allies—the ways in which an artistic, creative life can transmute the impact and redefine the legacy of an experience within the Prison Industrial Complex.

On his 18th birthday, rapper and spoken word artist RL Exclusive was transferred from the Cook County Juvenile Detention Center to Cook County Jail, having been tried as an adult at the age of 16. When new laws governing juvenile sentencing recently passed in Illinois, RL was freed and his sentence retroactively thrown out. Now, facing an upcoming retrial for his case just as his third mixtape is set for release, RL sat down with me to talk about his new music, the unique power of the Free Write Arts & Literacy program, and why labeling someone “troubled” has the potential to ruin their life.

Michael Fischer: You’ve been to somewhere around, what, seven high schools? What’s that been like for you? What was giving you any sense of stability through those years?

RL Exclusive: When I was getting expelled and going to all these different schools, I was still trying to find myself. But one thing that did keep me humble was my music. Through the process of me steady bouncing from school to school, getting into fights, getting kicked out, going to alternative schools, I was still recording. I recorded some of my best stuff, material I could re-edit and re-record and it would probably be some of my best. But back then I was still finding myself. You know, teenagers go through that rebellious stage. But I was still recording and that kept me humble.

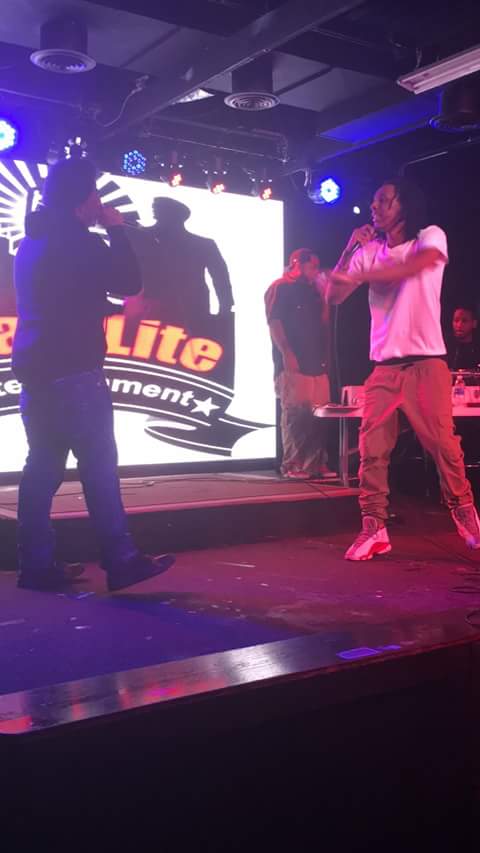

MF: I’ve seen video of you performing for the first time after your release. There’s a lot of energy in that performance, but you look so at ease as well, like you’re in your element. Talk about what it was like to be onstage after having been locked up for two and a half years.

RL: You know what’s crazy? I wasn’t even supposed to perform that night. I was with my brother and producer, his name is Jay Bucks. He produces all my beats, especially for this mixtape I got coming out. He was scheduled to perform that night, and he just wanted me to come to support him. It was a Young Chop event; whoever won, they’d get a free beat from him and some money.

When we got there, I guess my brother—I don’t want to say he got nervous, but once he saw how the energy was in the place, he was just like, “Bro, you should perform.” And it just happened like that. I ended up signing my name on the paper to perform. We were gonna split the performance in half, because I think they gave us like five minutes. He was gonna do two minutes or so of one of his songs, and we were gonna split the other time. He did his two minutes and thirty seconds, and then when my song came on—my song was like four minutes long, but they ended up letting me do the whole song because the crowd was feeling it so much.

That whole night was just crazy. I was on Facebook Live beforehand just keeping my fans updated. I’ll never forget that, because like you said, that was my first performance since doing two and a half years. And you’re right: I was at ease. That’s my element. I plan on doing a lot more of that right about now. I’ve got shows coming up, all type of stuff on the way.

MF: There’s a line in your piece Modern Day Slavery that says, “I am not a monster so please don’t be afraid of me.” How do you balance the artistic imperative to be vulnerable and express your humanity with the jail mentality that there’s no room for stuff like that—this idea that you have to be hard and emotionally closed off?

RL: Me as a person, being in an environment like that—being in the County or juvenile detention—like you said, you have to be like that. You have to be—I don’t want to say on go at all times, but you can’t show signs of weakness. But I know a lot of people that know how I’m coming. They know my personality. They know not to come that way towards me, and they know that I’m an artist. If somebody approaches me, they either want to fight me or they’re gonna tell me to rap to them. Nine times out of ten, I know the people who I’m into it with.

My people understand me as an artist. So it wasn’t like, “Oh no, I don’t want to say this, because they might not feel it.” I make music for everybody. I understand what type of stuff they like to hear. I had drill music; I still have drill music. I just don’t record it and publish it. That’s the type of music that they want to listen to. But they also know I have an artist side to me, like the poem Modern Day Slavery. So when I get on some spoken word type stuff, they won’t get on some stuff like, “Oh, I’m not trying to hear that.” They’ll listen to it and they’ll respect that, because I got their attention off rapping this drill music and stuff that they like to hear. And then once I’ve got their attention, I can go back to what it is I want to say.

So that line is like…let’s just say you’re a visitor coming in from the outside to inspect the County or something. You’re coming in here to Division 9, Division 11—a max division. Everybody here is fighting attempted murders, murders, rapes, all type of stuff. So you’re going to automatically have that perception in your head that these are not people I want to be around. You’re going to come in here with your nose already turned up.

When I said “monster,” I was exaggerating just a little bit, but that’s what you do in music. Sometimes you have to exaggerate a bit to paint that imagery in the listener’s head. But I do feel that’s how some people do look at us—and when I say us I’m speaking for everybody who’s locked up right now. I feel like they look at us like we’re monsters. Because you could be on your way to work in the morning, or just watching the news, listening to the radio and hear, “A fifteen-year-old kid just been locked up for a murder that happened uptown.” That could have been me. People could’ve judged me without even knowing what I’m capable of doing, just off of what they heard.

MF: You’re nineteen now. To me, one of the most infuriating things about how the criminal justice system works for someone your age is that the time delay between the alleged crime and serving the sentence is so long; you’re a different person by the time you’re actually punished. Can you talk about that, about what being kept stuck in the past like that by the system does to your ability to grow?

RL: I think that’s part of the reason why these new laws are getting passed, because they’re finally acknowledging that kids’ brains aren’t fully developed. I mean obviously I knew right from wrong, but I wasn’t making decisions as an adult. Kids get locked up when they’re fourteen, fifteen, I got locked up when I was sixteen. I know people who’ve been fighting cases for going on almost five years. That’s ridiculous. With a paid lawyer. How are you still fighting this case in the system?

Cook County is so big, and there’s so many different cases being fought, so when your time actually does come around, when it’s time to go to trial, you’re like four or five years older than you were when the case actually happened. It puts a strain on a person. It’s like, “Oh my god, I’m tired of steady hearing about this same case.” Innocent or not, you just ready to get it over with; you ready to cop out and take your time. I feel like they do that on purpose, so that you cop out to what they want you to cop out for.

Let’s say you really think you can beat the case, but they make you sit for five years. Who’s not gonna want to just get up out of there? You have to be so mentally strong. Also, the environment you’re placed in. Let’s say you’re in Cook County Division 9: max, the worst division in Cook County. The stuff that they do over there will make you want to cop out and leave. It’s an everyday thing: they fighting over there, spraying feces around, beating up the COs, you on lockdown all day, they stabbing people. Who wants to be in that? Who wants to wake up and go to sleep to that, with a bunch of lunatics on drugs? So I feel like the system, they know what they’re doing. They stretch things out longer to put that strain on you so they can get you to do what they want you to do. That’s how I feel.

MF: Did I see video of you sitting in your car outside the County? What’s the story there?

RL: My sister was going up there to see a close friend of ours; she asked if I wanted to go. I don’t like my sister or anybody in my family traveling around Chicago without me. When she told me where we were going, I thought, “Should I go, and see that place one more time?”

When I got out of the County, I said I never wanted to see it again. But me taking that trip with her, it humbled me. It reminded me where I came from; it reminded me that I didn’t want to go back. Because actually, from the gate where I was sitting at, I could see Division 9. I could see all the inmates on the patio playing basketball. I was just on the other side of that fence, doing what they’re doing, and now look at me: I’m out. I can move, I can do whatever I want. I can get in the car right now and pull off, and they can’t. They’re still in there fighting for they life, and they don’t know when they coming home. Somebody was probably getting stabbed in there right while I was sitting there. So it humbled me and reminded me that I’m not going back. I’m not. I’m not. That’s all that was.

MF: Your third mixtape, My Brother’s Keeper, comes out June 15th—the same day your trial begins. There’s a number of references you could be aiming at with that mixtape title. Which allusion are you trying to invoke with that phrase and why?

RL: The title came from my circle. When I say my circle, I mean the people that I surround myself with. I don’t have friends, because I’ve had experiences in the past where people stabbed me in the back. I’m a loyal person and I feel like my loyalty was a part of my downfall in some ways. You don’t have to be my blood relative to be my brother. Yes, blood is thicker than water, but love is thicker than blood.

What I mean by that is: I could’ve known you for ten years. You know my mom, I know your mom. Then over here, this is my blood brother, but I haven’t grown up around him. Now there’s a predicament where I’ve got to make a choice: you or him. Well I’m gonna choose you, because you’re who I know. I don’t know what he’s about. Yeah he’s my blood, but I don’t know him.

This mixtape is dedicated to my homie EJ, Eric Jordan. I lost him November 14th, 2015 while I was locked up. It’s partially dedicated to him and also to my brother C Kobe, he’s still locked up right now. When you see the mixtape art, it’ll give you a better understanding of what the mixtape is going to be about, but it’s basically just talking about my brothers. I’m showing you what loyalty should look like and what it should sound like. I really can’t say too much, but when you hear the mixtape, it’ll explain everything I’m trying to explain right now.

Speaking of the mixtape title: I just did a show in Detroit. We went out there and we were working with a group of—I hate to say “troubled kids,” because I was once in the same situation as these kids. They’re basically in like a boarding school setting. I know how it feels to be in that, because I’ve been to boot camps, all type of placements. So when they told me we were going out there to work with these kids, I guess they expected to mind my Ps and Qs or be uncomfortable or whatever, but I was just going to be myself.

Now before I performed, the kids had written some poems and we recorded them, so I got to know them from an artistic standpoint. Some of those kids did have some talent; some where trying to rap or whatever. And me—look, I’m a real street nigga, so I can tell if you’re trying to portray something that you’re not. I can spot that from a mile away. These kids come in there talking all this Chicago lingo—and yes, I take pride in it being our lingo, that being Chicago lingo. I feel like the industry has been using our lingo a lot.

I’m just observing these kids, not saying anything, just a fly on the wall while they record. One of the kids actually asked me, “You from Chi-raq?” Like he wanted me to give him some of that gang persona type stuff, but I didn’t. I spoke to him like I’m speaking to you, and I think that threw him off a little bit.

I waited until after the show, once I had their attention because I’d just killed the performance like I always do. We were in the cafeteria at this school just mingling, talking. I used that opportunity to pull all these kids to the side and just talk to them without their staff being right over they shoulder, so I could talk to them how I wanted to talk to them—beyond Scared Straight type of stuff.

I asked a couple of them, “Okay, which one of ya’ll gang bang? Because I saw ya’ll throwing up gang signs and whatever.” Remember, I’ve got their full attention by now, because they just watched me perform and they know my stuff now. And a couple of them spoke up: “Oh yeah, I gang bang, I’m from this set” and all that. I’m like, “Okay.” I went into depth and explained to them that this isn’t what ya’ll want. This gang banging life that ya’ll trying for, it’s not what you want, I promise.

I had to give it to them blunt. I’m from Chi-raq—and I say Chi-raq, because that’s what my city is right now. I had to let them know: “I just gave two and a half years of my life away for that, for what you guys are trying to do right now. Sitting here talking about gang this, squad that. Where they at right now? Ya’ll in here fighting for ya’ll life, don’t know when ya’ll getting out. Who ya’ll think you’re coming home to? They not writing ya’ll. They not sending ya’ll no care packages, nothing to make sure ya’ll good. Ya’ll moms are doing that stuff. So why ya’ll trying to put your life and your freedom at risk for a group of niggas that wouldn’t do the same for you?” Once I gave it to them like that, it connected instantly.

Basically, on that trip, I gained a whole bunch of little brothers. That’s how I consider them. That’s also part of being my brother’s keeper. Because kids like that, dealing with the situation that they’re in, I know how that feels. So I want to be the voice for that. What other rapper is speaking up for kids like that? Nobody. I’m not saying I’m trying to profit off of them; I’m one of them. These kids can get a hold of me when they get out.

MF: That’s really interesting, what you said about this label of “troubled youth” and “at-risk youth,” and how you can relate to that because you’ve been labeled that way. To me, those kinds of labels are self-fulfilling prophecies. These kids aren’t stupid; they know you’re calling them by these names, and now you’ve put that in their heads: “Now you’re this.”

RL: I’m glad you said that, because while I was going through different schools, getting locked up different places, I kept on hearing, “problem child, he’s a problem child.” Not from my mother—not once in my life has my mother ever called me a problem child. She still won’t. But I used to hear that a lot. I would think, “Okay, I’m a problem child. So now I’m gonna be a problem.”

It is a self-fulfilling prophecy, like you said. If you’re steady telling these kids they’re trouble or they’re juvenile delinquents or whatever, you’re putting that into their heads and then locking them up in these cages, and it’s messing with their heads. They’re starting to believe it, thinking, “Maybe I am troubled.” Because I know I questioned myself, like I’m sure we all do. “Why would I do that?” Well now you’ve got the answer: because you’re “troubled.” You’re “at-risk.”

That’s why I want my music to hurry up and get out, get myself global and not just local, so I can speak to these kids and let them know, “Ya’ll not alone. Everything that they telling you is a lie; there’s nothing wrong with you guys.”

You’ve got to talk to these kids, not just dope them up on drugs and sit them in a room. I know when I was locked up, there were kids who would get medicated and just go in they room and sit there. I remember I met this one kid in there, when I first knew him he was so full of energy. He had personality, and now he’s just like a zombie walking around. I know people personally who got out after being put on drugs like that and now they’re still the same way—they mom asking, “What’s wrong with my kid?” Well what’s wrong with your kid is that they gave him some diagnosis and gave him all these drugs, thinking that they’re helping him, and now he’s stuck like this.

So I hate those titles, the way they paint a picture in your head that doesn’t belong there. You start to question yourself, looking in the mirror thinking, “Am I? Am I really all of these negative things?” Words are powerful things, and if you keep saying something about somebody it might eventually come true.

MF: All that being said, what about Free Write was different for you, as far as being a program aimed at a particular demographic? What did [Free Write founder Ryan Keesling] bring into the juvenile detention center that spoke to you in ways that those other programs didn’t?

RL: First of all, shoutout to Free Write. Shoutout to Roger, Ryan, Elgin, the whole team. I love you guys. I think one of my staff pulled me aside and told me about Free Write, because I was known even in there for making music. I’d been asking for more programs, because I spoke up in there. A closed mouth don’t get fed; I didn’t want to keep sitting in my room.

So me and a few other guys went to check it out. When I went in that room, I automatically fell in love, because in the Free Write room in the detention center, they have a microphone. That put the biggest smile on my face and I just zoned everybody out. And that’s when Ryan was like, “Hey, how you doing?”

At first, I really was just coming there to use the microphone. I was like, “Okay, I get what you guys are saying and that’s cool, but let me get on this microphone.” That’s how I was looking at it. But then they explained to me what the program was about, how they help kids just express themselves in any type of way. It’s Free Write Arts and Literacy: you can come there and draw, there’s people displaying their talent and being free in their talent, and I love that kind of setting. There’s kids in there drawing, making beats on the computer, and there I am with the microphone.

When I met the guys from Free Write, they were very down to earth people and they still are. They made you feel comfortable, because they could’ve just had people in there going, “Alright, there’s a computer; go record. There’s some pens; go draw.” No, they actually interact with kids and ask them what they like to do and how they like to do it. They try to give outlets. They let me listen to music. I love music and I hadn’t listened to music when I was in there for like a year. They even helped me perform because they have little events in there, so I performed a couple times.

Now here I am: I’m still working with them, getting out in the community, still going strong. Now they’re part of my team and I’m proud to say that.

MF: I remember hearing guys boasting, saying, “I’ve got another bid in me.” I don’t; I never understood that, or why anyone would be thinking like that. And the sad thing is that just because of how young you are, a lot of guys inside would lay that on you and say that you’ve got another bid in you. Obviously you don’t, because you’re doing great things out here, but talk about that idea of “I’ve got another one in me,” as if that’s something to be proud of.

RL: You know, I ran into a lot of people like that while I was incarcerated that used to say that. It used to infuriate me. Sometimes I would bite my tongue but sometimes I would speak up and it would end up being these hourlong debates about why you feel like you’ve got another bid in you. Then some old guy would walk up who did twenty years, got out, did another ten, something like that, who would mediate the whole situation.

I hate that, like you just said, when people look at me: I’m young, I’m full of life and full of energy, and they think, “He’s got another bid in him.” Don’t say that to me, don’t say that about me. Because first of all, you don’t even know me or what I’m fighting, what I’m going through or what this situation is doing to my family. You don’t know who loves me or what they’re going through. How could you say something like that?

I feel like they’re brainwashed. Because the truth is that some people, when they’re out here in the real world and they’re not in jail, they’re nobodies. I’m sorry to say that, but it’s true. They don’t have a role to play or people who love them. When they get in jail, they become these so-called role models in jail, and they become a somebody. They find a sense of being somebody and they like that, and that’s why I say they’re brainwashed. They want to be in jail.

I know people who beat their case and got out of jail, were out for a minute—and before they even left were already saying, “I’m gonna get out there and do the same thing.” I’d try to talk to them before they even got out, but sure enough, a couple weeks later, somebody comes in and it’s the same person who just left. They never change; it’s that same mentality and it’s sad. So I’m like, “Don’t wish that on me. Don’t tell me I’ve got another bid in me. If you’ve got another bid in you, if that’s how you feel, then that’s you. But don’t wish that upon me.” Because like I said, words are powerful things and I feel like anything you say could eventually happen.

MF: Other than the mixtape, what’s the next thing you have coming up that you’re excited about?

RL: Right now, my main focus is my mixtape, I’m not gonna lie. I have radio interviews set up—my schedule is so hectic, but that’s a good thing. It’s positive stuff. I’ve got video shoots, I’ve got a studio session tomorrow, I’ve got other stuff to look forward to, but I can’t really see past my mixtape right now. It’s 24 days until my mixtape comes and I don’t have enough notoriety; I don’t have enough clout yet. I’m not sleeping because there’s no point in me sleeping. I just did two and a half years of sleeping. I don’t want to sleep.

So everything for these next 24 days is all about my mixtape; you know I’m dropping my mixtape the day I go to trial. So while I’m in trial, deciding what’s going to happen with the rest of my life, you guys will be listening to my mixtape. It’s gonna be a classic, the best mixtape of the year. I promise you that. Make sure ya’ll stay tuned.

RL Exclusive’s first two mixtapes are live on datpiff.com. His third, My Brother’s Keeper, will be released on June 15th. Follow him on Twitter @YOUNGEXCLUSIVE and on Instagram rl_exclusive

Do you enjoy what we do at Sixty? Please help keep us going by making a contribution today.

Featured Image: RL Exclusive with Jay Bucks

Michael Fischer was released from prison in 2015. He’s a Moth Chicago StorySlam winner, a Luminarts Cultural Foundation Fellow, and a mentor for incarcerated authors through the Pen City Writers program. His work appears in Salon, The Sun, Orion, Guernica, The Rumpus, and elsewhere, and his audio essays have been broadcast on CBC Radio’s Love Me and The New York Times’s Modern Love: The Podcast.

Michael Fischer was released from prison in 2015. He’s a Moth Chicago StorySlam winner, a Luminarts Cultural Foundation Fellow, and a mentor for incarcerated authors through the Pen City Writers program. His work appears in Salon, The Sun, Orion, Guernica, The Rumpus, and elsewhere, and his audio essays have been broadcast on CBC Radio’s Love Me and The New York Times’s Modern Love: The Podcast.

.