Art is affecting and hope-filled, expressing all the things words cannot. Cultural objects and experiences hold the power to reveal what is hidden about the world and ourselves, and artists act as conduits to these truths. While their ability to translate knowledge through visual and temporal experiences is remarkable, let us not forget that art at its core, is a technical skill that requires practice and study like anything else.

I spend a lot of time visiting artists’ studios, learning about what factors inform their practice, and thinking about how their encounters with me might affect the objects they ultimately create. Creating community and generating dialogue through art is the ultimate human negotiation, a relational push-pull and give-get. The artist’s studio is a system, a constellation of ideas, people, and decisions that ultimately influence the objects and experiences produced. Recently I met Chicago-based sculptor, curator, and arts administrator Faheem Majeed at his studio where we talked about what motivates his multi-disciplinary practice. Welcome to the conversation!

Lee Ann Norman: Your practice encompasses many roles from artist to teacher to administrator and curator. On the surface, they all seem quite different. Can you talk a bit about how you bring them together?

Faheem Majeed: I was trying to piece together a living. I had my feet in the teaching world [at Little Black Pearl Workshop], and when I was at the South Side Community Art Center (SSCAC), I carved out my own idea of curation. I didn’t have any training, but took [from] what I understood to be good shows and the idea of what SSCAC understood and needed a curator to be, and was able to be successful.

LAN: I think it’s connected because we are asking questions about art: [The work of] a curator overlaps with [that of] the historian, and the critic, and the artist. We come to [art] objects and experiences from different angles – even our work as administrators – because in the end we are all asking questions.

FM: Yes, and I say that’s out of necessity. In an ideal world, I [would] come to Chicago and be able to make a really good living as an artist, but if that were true, we probably wouldn’t be sitting here talking about these things. But it’s also about passion. I figured out how to have my cake and eat it too. At first I thought my artwork needed to be separate from my administration, from my curating – a very compartmentalized way of thinking. Once I was able to define that as an art practice – this kind of institutional critique and challenging ideas about art in Black cultural spaces – that’s when things started to get really interesting. [When] the exhibition The Demise of the Southside Community Art Center (2009) happened, people started to open up and I realized that I wasn’t isolated in this; everyone has a duality in their employment and personal life.

LAN: Sometimes I feel ambivalence about those frustrations because you are doing this thing that you love. However, this thing that you love is hurting you. (laughter)

FM: You just hope that it’s going to change its ways and [that] maybe if I do this one thing, it will change a little bit. As I’m doing these things, I’m moving around the city–the Art Institute one week, the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) the next, the Smart Museum, the Renaissance Society. I start connecting with administrators because I understand that perspective of feeling like a cog [in the machine] in one instance, yet in another working between the grain to hit on something really important. My role as an administrator – to be sympathetic and empathetic – has really helped me connect with people and organizations. I can relate to the challenges that arts administrators face. Often times, my work captures some of those ironic frustrations.

LAN: I’m sure your understanding of how various institutional structures work along with your own work as an administrator helped you as you moved around. Was there anything that you learned or something that surprised you as you started working this way as a practice?

FM: I was surprised by the way many important decisions and ideas are seeded. There’s so much power in being in the right room at a certain moment. Sometimes it seems like the biggest decisions can be based on a casual and impactful encounter, when someone has an “ah-ha” moment. I go into situations now with the expectation that everyone is good at heart and wants the same things: make some money, have healthy lives, raise their families, but too often, it only happens in our own spaces, so we aren’t able to see how significant or insignificant their roles are. There are valuable things that happen in my neighborhood, and there are valuable things that happen other places. It’s about leveling visibility for all of these things.

LAN: This speaks to the nature of culture and how it happens, particularly here in Chicago. Part of what is so amazing [about living and working here] is that there is so much space, filled with clusters of activity, but the mileage people have to cover to experience the range of things happening in the clusters becomes a barrier. I remember living in New York and thinking how easy it is to literally tumble out of a spot and run into people – very, very different people. In Chicago, it’s not so easy to do that.

FM: This is a city rooted in segregation. Not only is diversity challenging to human nature because we tend to gravitate toward the familiar, but there’s also a systemic plan geared toward segmenting and separating individuals. Even after those walls have been removed, the behaviors tend to remain. Only a handful are able to step out of it, and by stepping out of it, we acknowledge that there is a system in place designed to keep us apart. When people say, “I’m from the West Side” or “I live in Humboldt Park,” that’s a political statement. When I moved here that meant nothing to me, but I understand now. It’s a politic deeply entrenched in Chicago. South Shore [residents] will never be on the bus with Lincoln Park [residents]. Here, if we want those kinds of encounters to happen, we have to be very intentional.

LAN: Part of your work is about informing others, raising awareness, and value. You’ve mentioned that your education and exposure in arts wasn’t standard and that your canon was different. When you went to graduate school and your classmates were talking about Duchamp or chance operations, you felt a little out of your element. How did you begin to reconcile differing notions of value?

FM: At the time, my work was very figurative and Giacommeti-esque. I was starting to experiment, but I needed space to process that. For a long time, I felt ashamed and embarrassed about my lack of art historical knowledge. I went to Howard University, which has an approach of pumping students up with really powerful examples of African Americans in the arts who were really successful – the William H. Johnsons, the Richard Wrights . . . this was my base. When I got to Chicago and the SSCAC, [my base was] still African Americans, but they’re from Chicago. Instead of having to read about them in books, I could talk to them in person. This conversation wasn’t happening in graduate school. I was the only Black student – actually, the only Black person – in the program. I felt out of place and isolated. But there was a moment when I was able to shift the power dynamic. I began to leverage my particular art historical knowledge in a space where that information wasn’t accessible. I could learn all about the Duchamps and [Walter] Benjamins, but the reverse wasn’t happening. They might ask me if I know Jaspar Johns, and I began to ask if they know William Walker. I started presenting those artists [from my canon] through platform making, production, curation. I was name-dropping the way others were, without giving any information, and they experienced the frustration I had felt.

LAN: Right; they were making assumptions about what you should know and now you were doing that to them.

FM: Once I started to realize I’m not a minority, but maybe the authority, that changed everything. I became a lot more transparent in how I communicated about my work and influences. Much of the information I had isn’t written; it’s lived.

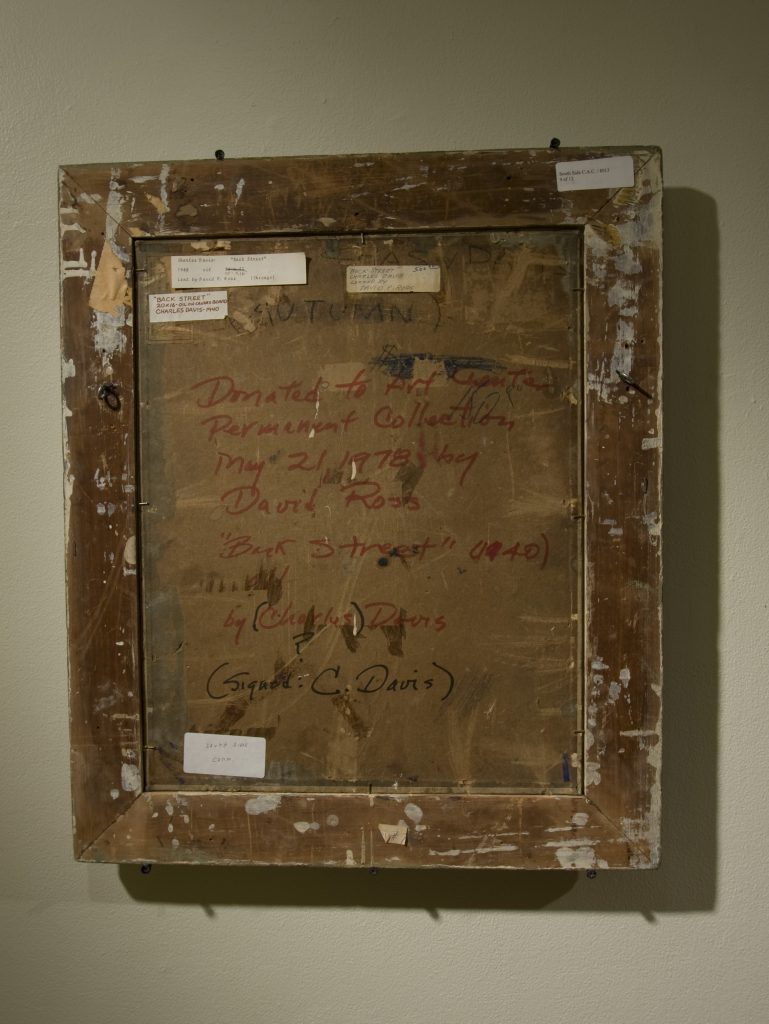

Once, I created an installation of work I brought work from the SSCAC’s collection. While I was in school, I became Executive Director, but I didn’t tell a lot of people [in the program]. I had incredible access and didn’t know what to do with it, or how to talk about it. I brought in five paintings (but I turned them around) from different periods, a couch, and five lamps from a predominantly Black space to a predominantly white one at UIC. People felt I was editing the intention of the artwork, since I wasn’t showing the front, but [from my perspective] the intention was to make a power move. When artists have shows and their artwork is returned, labels are often put on the backs of the pieces. The labels can be anything from prices, names of ownership, little installation notes . . . so all of these stickers had built up from years of circulation for these works. I called the work Provenance (2008) because the stickers might be more meaningful to viewers than the actual face of the artwork.

LAN: This was also marked a shift in materials for you. You are not working with traditional sculpture materials so much – not a lot of bronze or steel. Those choices are political as well. How did your experimentation with materials develop during this period?

FM: I’m still a “metal head” at heart, but I haven’t welded in a while. There’s a smell, a feel to it that I love. There are things I learned at Howard that I thought everyone was learning, but once I left, I realized how special that education was. I worked in re-found steel, learning how to rummage through an alley, re-use materials and make what I needed or climbing through a demolished building or gathering railroad ties and pipes. I never knew how to work any other way. I didn’t know it at the time, but Howard didn’t have a budget [for metal work].

LAN: I wondered because it’s really, really expensive to go to the foundry or create molds! (laughter)

FM: Foundry?! I didn’t get to the foundry until I was in Minnesota [after Howard] working for a rich bronze sculptor. That’s when I tapped into it, but never went back because it wasn’t something that was easily accessible. I have experience going through trash, finding what I need, making it look completely different, and putting [the material] back out there. This is how I made artwork. But I was moving away from metal even before graduate school. My thinking shifted from using steel to capture my ideas to letting my ideas dictate the right material to use. I made Shacks and Shanties (2012) from found wood and material in the neighborhood. It was really about finding the best material at the time to get the idea across. Now I’m moving into painting and collage. I know I’ll go back to metal, but I just need to make sure I’m not working with the material for the sake of material.

LAN: You’ve talked about how your practice is akin to a small arts nonprofit – mission driven, considering how the actions you take support the communities you work with, the artists you are invested in. You are interested in questions related to effectiveness. How does your current work, Floating Museum (2016), help you address that?

FM: I sit on a lot of diversity committees [at large cultural institutions] and hear questions all the time about how we can engage the community more. That’s kind of an empty statement, right? But my collaborators and I recognize the need for this. We hope we can get to true, sincere conversations, get people to stop saying empty things like “community” and “diversity,” and get to creating sustainable connections. Often we have these conversations [that] try to pinpoint people’s needs and try to put ourselves in other people’s shoes, but what we should be doing is simply having those shoes in the room.

LAN: When we think of museums, we think of history and legacy, but when we think of culture, it is bound; yet it is fluid. Sometimes it doesn’t feel like the institutions charged with educating, displaying, and collecting the culture are as responsive or nimble.

FM: I think of it as a question of language. I understand the perspective of working month-to-month and planning shows for 3 years out. Floating Museum is trying to set an example of potential as well as actualizing settings to help translate those perspectives through advisory meetings and engagements. Once you learn the language of a space, you can effectively navigate it. This isn’t about critique so much, but how to offer support. We don’t want to get rid of the model because we value it, but we want to support. And we’re not trying to “guerilla” the institution, because part of this is about working through the system–going to the Art Institute, for example, to get image permissions, etc. We want to get to the point of exchange. Part of the artwork is getting the access, learning how to negotiate and navigate these relationships with institutions.

For more on Faheem Majeed’s work, visit faheemmajeed.com.

Featured Image: Faheem Majeed, Self-Portrait, mixed media, 2010. Image courtesy of the artist.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Lee Ann Norman is a writer and culture maker who works between Chicago and New York City.

Lee Ann Norman is a writer and culture maker who works between Chicago and New York City.