At twenty-one, I stood at the crossroad of Hell

& Here, evil peering at me behind a blue-red eye. I armed myself

with the memories of Pentecostal tent revivals, apple orchards, the

strawberry fields I roamed with my mother & aunts in the summer,

& the sightings of UFO lights blinking in the black of an Ohio

nightsky. I am a weapon.

–Krista Franklin, from Manifesto, or Ars Poetica #2

I describe Krista Franklin as a poet and an artist only for the sake of offering an entry point into her work. It’s true–she is a fierce wordsmith and maker who moves naturally, yet distinctly, between words and paper. Those of you who know her work may be equally as familiar with the rhythm of her prose as you are with the beguiling tactility of her collages and handmade papers. You may know it at first sight or sound. But the initial encounter one may have with her work is simply an enchantment, a quick and captivating tool that forces a pause. Once you stop to stand still and sit between the lines or underneath the layers, there are pasts, presents, futures, and other worlds being agitated and conjured. With fluency, Franklin makes visible places and intelligences that are accessed by anointed scribes who have taken on the responsibility of translating the cultural and social detritus of humans, androids, and ancestors into a language that we can begin to understand.

Franklin is a storyteller and a vessel for well-known histories, things unwritten, and realities that have yet to be, which is why defining her as only an artist or a poet is inaccurate. Her work demands that those titles be interchangeable with historian, educator, caretaker, life scholar, ethnographer, anthropologist, and receiver.

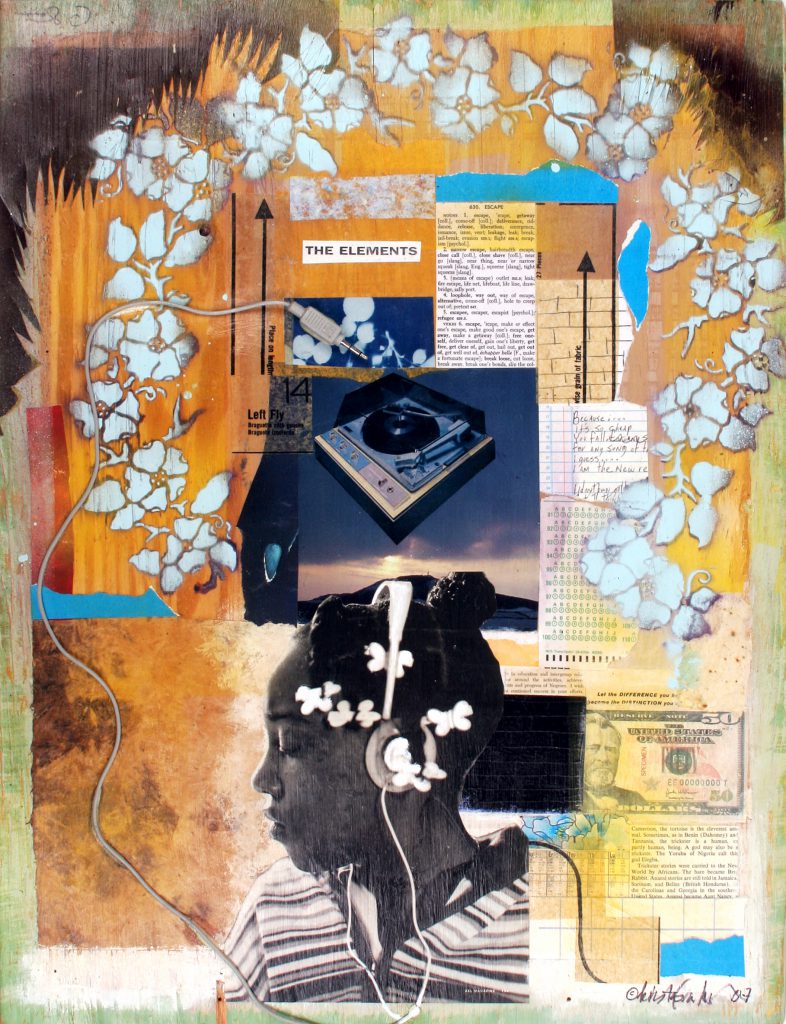

Her flow between roles is mimicked in the work that she makes. In poems and on paper, Franklin reveals herself as a master sampler who builds bridges between a vast range of elements and references within a profound sea of influences and experiences. Each work comes with its own laundry list of liner notes and citations. To describe her work I could as easily cite the poetry of Fred Moten and Amiri Baraka, writings of Ishmael Reed, or the worlds of Octavia Butler as I could the collages of Hannah Höch and Romare Bearden, or the chameleon-like characteristics of Grace Jones or Prince Rogers Nelson. I could use the lyrics of Bad Brains, the album covers of Parliament/Funkadelic, the music videos of Outkast, or the echoing sound of voices that linger above 47th street in Chicago on any given day to bring it back into a place of Black sonic culture. Then, within the same breath, I could speak about the recurring lyrical and visual motifs that show reverence for the grace of Black women, youth, and street scholars while channeling the supernaturalness of veves, afro picks, cowry shells, and global Black memorabilia.

Then there’s how she lays plain the underbelly of these mondes, expressing truths often thought but rarely said, as messy and monstrous as they may be. She does not discriminate between the celebrated and condemned strata of the landscapes she traverses. Unflinchingly, she approaches them with an unconditional love and discerning eye whereas most people would be left stunned, shook, and fleeting.

By sharing her origin story, Franklin offers traces, not a blueprint. She is one of those artists whose style and technique is often imitated but never can it be duplicated because her radial disposition is organically constructed through insatiable curiosity, instinct, and learning through living, making her process and approach distinctly her own. The Krista Franklin blueprint can and will never be written down. Instead, she will leave you with shapeshifting breadcrumbs so mighty and nourishing that you’ll feel full while eventually realizing what you actually got were hors d’oeuvres. In our conversation she offers some insight into the seeds of her life’s work by starting from the beginning.

Tempestt Hazel: Since you’re such a pillar in Chicago some people may think you’re from here when, in fact, you’re from Dayton, Ohio. What was it like growing up there?

KF: I grew up in a racially mixed suburb in Dayton, Ohio. The majority of my friends and neighbors were white, which, for the most part, was a non-issue for everyone around. It was fairly idyllic. We all played together, rode bikes together, went swimming together, went roller skating together, danced, and did homework together. We were all up at each other’s parents’ houses listening to music, watching TV, or whatever. What I remember most about growing up in Ohio has been chronicled in a lot of the poems I’ve written. I remember there being a lot of space; space to think, space to breathe, space to roam. The natural world was pretty prominent where I grew up, so trees, the woods, birds, creeks, minnows, deer, raccoons, possums, cats, dogs, cornfields, all that was present. There was also a good deal of quiet time. It’s slower than Chicago, so you don’t have a whole lot of distractions. If you want distractions, you have to create them.

I had a lot of freedom growing up in Ohio. I often think about and mention all of the brilliance that’s come out of Ohio in general. Nikki Giovanni, Toni Morrison, and Rita Dove were all reared in Ohio. One of Dayton, Ohio’s claim to fame is that it’s one of the seats of funk music – Ohio Players, Slave, Heatwave, Lakeside, Zapp featuring Roger (Troutman) – all out of Dayton. The Wright Brothers set one (if not the) first flight into motion in Dayton, Ohio. Ohio is a magical place to grow up really.

I’m convinced that the reason that I’m the artist and poet that I am has everything to do with being Ohio born and bred. Ohio is not without its troubles and pathologies, but growing up there and coming of age there in the ‘70s, ‘80s, and ‘90s deeply shaped and impacted the way that I see the world, the way I move through the world, and the way I process things.

TH: What is your first, most vivid memory from your childhood?

KF: My earliest memories from childhood have to do with the night. One of my first memories is figuring out how to climb out of my crib because the curtains that my parents put on the windows in my bedroom terrified me. There was a pattern on them that looked like faces to me and I wasn’t having it. I remember climbing out of my crib, scaling my way down in those pajamas with the feet, and walking into my parents’ bedroom to get in the bed with them. I think my mother was shocked as sh*t when I started calling her name in the dark. It’s like, “Dang, this child figured out how to climb out of her crib.” It was over from there. I was on the roam.

TH: What were you like as a kid and into your teenage years?

KF: Who knows really. That’s probably a question for the folks who knew me back then. But I remember truly enjoying my solitude as a child, and being bookish, and nerdy and awkward as a teenager. I watched a lot of television, and walked to the mall and spent a good deal of time there. When I was in elementary school, there was an annual school-wide poetry recitation competition that my mother made me participate in every year. I had to memorize a selected poem and perform it in front of a group of judges. I won second place every year which eventually started to make me feel terrible, and there were whispers in my family that my race may have played a part in that annual second place ribbon.

In junior high and high school I began to take on the cloak of being an outcast and an outlier, and developed a kind of disdain for those who I saw as “popular.” I loved English class and Art class, and hung out with the punk kids and the skateboarders. I bought magazines all the time and read them from cover-to-cover and bought albums and cassettes weekly at the record store. Most of my money went to music. I went to the movies by myself a lot and spent time at my friends’ houses or in my room at home. I remember getting turned out by Henry David Thoreau’s Walden in one of my classes when we had to read it, and I remember in my senior year reading about Jean-Michel Basquiat’s death in one of my magazines. I also remember seeing my first Andy Warhol as a teenager at the Dayton Art Institute with my punk boyfriend and one of my best friends. I wore black a lot and was pretty sullen. My father used to call me Johnny Cash.

TH: When did you first suspect that you might want to make a career as an artist?

KF: I never know the answer to this question because I always wrote and made art since I was very young. I would write poems as a teenager and then read them to my mother while she was doing her make-up or cleaning the house. My whole family knew that I was an artist and would always call me a bohemian, but there were no models or maps for how people became professional artists in my family. It was always seen as my “hobby,” and my mother, father, aunts and uncles were always asking me what I was going to do for a living and what was I going to grow up to be. I didn’t even think being a professional artist was possible, but I thought that I could probably figure out how to write for a living (as a journalist). In undergrad, I started writing pretty seriously and publishing and studying, and developing a political consciousness around Pan African issues. I hung out with designers, musicians, photographers and poets, and I spent hella hours in the library combing the stacks. I was just living really. I had no idea what I was going to be for years. Sometimes I think I still don’t know.

There was really no one definitive moment when I decided to make a career as an artist. It was a series of moments, experiences and people who encouraged me, and told me that my work had merit. I followed that impulse inside of me to make and write, and somehow I landed here.

TH: You spoke of this a bit before, but when did poetry first enter into your life? What poets and writers have been significant influences on you?

KF: It first entered my life in those poetry recitation competitions in elementary school. However, my mother and her sisters were teachers in various capacities, and my aunt Maria in particular had a wonderful collection of books that I would browse and there were a lot of black poetry books I was exposed to early. My mother also wrote poetry for fun; very traditional rhyming poetry that she would read to the family. Most of them were funny because my mother has a great sense of humor and likes shenanigans. There was always a lot of singing and reciting of poems between my mother and her sisters, and I was exposed through them to the art of transforming memory into art through storytelling and clowning around. It was all really quite poetic.

On Christmas of my seventeenth year my mother gave me The Selected Poems of Langston Hughes, and I spent that entire day reading that book. It was the “A-ha” moment for me around poetry. I remember just feeling this joy around that writing and around what words could do in a concrete way. The other writers and poets who were very influential on me early on were S.E. Hinton, Judy Blume, Gloria Naylor, Alice Walker, Toni Morrison, Sonia Sanchez, Nikki Giovanni, James Baldwin, Audre Lorde, Isabel Allende, Greg Tate, Amiri Baraka, William S. Burroughs, Anne Sexton, Erica Jong, Willie Perdomo, Octavia E. Butler, Katherine Dunn, Philip K. Dick, I could go on and on. I would also be remiss if I didn’t talk about the influence that hip hop MCs had on me and my writing and art: Chuck D (of Public Enemy) served as one of my most significant writing influences. There are many, many others though.

TH: Anyone who has heard you read your poetry knows how captivating of an orator you are. Is this something that came natural to you?

KF: I don’t believe in oration coming naturally. If someone is a good performer or orator you can pretty much guarantee that they practiced to be so. Again, I learned as a child in those dreaded poetry recitation competitions, but I also learned a lot from preachers in church, and from the women in my family who were constantly “performing” for each other through telling stories and sharing memories with each other in a very dramatic and hysterical fashion. Also, listening to all kinds of music, but hip hop in particular, taught me a lot about how to emote and move a crowd.

TH: When did visual art make its way into your practice?

KF: Visual art was always a part of my practice, even in my poetry. I always talk about my poetry being in the “Imagist” tradition. I believe that the most powerful poems are pictures painted with words. I always drew and doodled and made images on paper even as a child. My mother still teases me to this day about how I always had some “project” I was working on. I had this series of small books I created as a child using an ink pad and my thumb print. I would draw images around my thumb print. I think the series was called “Thumbody Loves Me,” or something terribly corny like that. I may have even been trying to sell them to people.

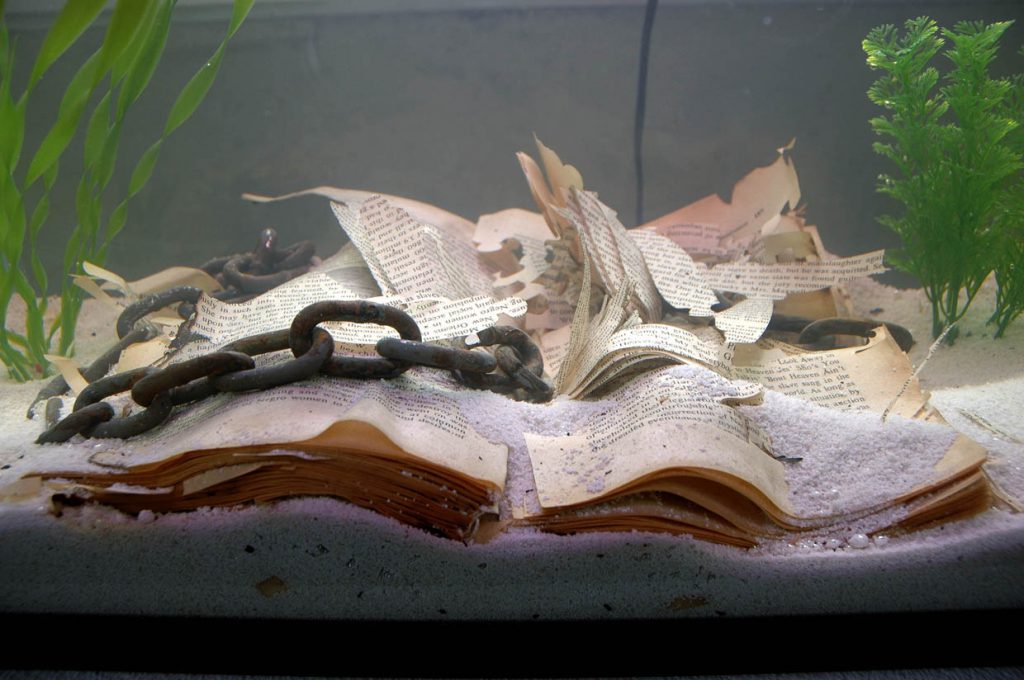

I began seriously making mixed media collages in my mid-twenties, and it was something that I did when I was afflicted with writer’s block. However, it wasn’t until I moved to Chicago and other artists and poets became aware that I was making them that I put them in the public eye. It was really at the encouragement of my artistic community that I even considered exhibiting and showing my visual art. It was always just my little thing that I did for myself to shake the words loose in my brain; the pathway to more poems.

TH: Before you came to Chicago, you went to Kent State. What were some of the most significant moments from your time there?

KF: Oh, my God. There are too many to name really. Kent State University is the site of my evolution from being a teenager to an adult, of becoming politically aware, intelligent and active, of developing my identity as a writer, of meeting other people who were like me and thought like me. I always say that the murders of those students on May 4th, 1970 by the National Guard (who were also young people who were afraid and confused) left some really powerful energy on that campus. May 4th, 1970 was two months before I was born. Sometimes I would feel so much sadness and rage on that campus. It fueled my political development.

Here’s a few significant moments: sitting in the quad outside the Student Center listening to Ice Cube’s Amerikkka’s Most Wanted on my headphones; standing with Black United Students and watching the Nation of Islam usher in a speaker we invited to the campus; reading and talking about Toni Morrison’s Tar Baby in my Black Women Writers course, and having my brain explode from the beauty and complexity of that text; pulling up to the campus after a summer break blasting Prince’s “Alphabet Street”; interviewing Giancarlo Esposito for the Black United Students’ magazine Uhuru when he came to the campus to talk about being an actor in Spike Lee’s movies; meeting and laughing with Q-Tip and Phife Dawg in the auditorium hallway with my friend Katika Thomas when A Tribe Called Quest came to campus to perform; interviewing Dove from De La Soul for Uhuru Magazine when Buhloone Mindstate dropped. I could be here listing things all day when it comes to Kent State.

TH: Why did you decide to move to Chicago?

KF: I moved to Chicago on a whim in 2001. My best friend Folade Speaks and I made an agreement to apply to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago’s Writing Program for graduate school. She applied and I didn’t. She got accepted and moved to Chicago. I stayed in Dayton. After her first year, her then-roommate, Kenyetta, called me and told me she was relocating to New York, and I should move to Chicago and take her place in the apartment. I told her she was crazy, and what in the hell did I look like uprooting my life to move to Chicago with no job or any real reason to move there? We got off the phone, and the next day I called her back and said I was coming. I gave away everything that couldn’t fit in my Toyota and drove to Chicago. I’ve been here ever since.

TH: It’s clear that music is important to you–Chaka Khan, Ohio Players, Michael Jackson, 2Pac, J. Dilla, and so many others have appeared in your words and visuals over the years. Can you talk about the role music plays in your work?

KF: Music is the underscore for everything I do. It’s the pulse of everything I make and write, really. I don’t even have a clear way to articulate the role that music plays in my work. It’s such a non-factor because it’s just so present. For years I was the girl who had the most formidable music collection of any of my friends. I mean, the music industry probably earned hundreds of thousands off of me throughout my life. Seriously. My visual aesthetic was cultivated by my father’s album collection in the 1970s and videos on MTV and BET in the ‘80s and ‘90s. My poetic voice was partially cultivated from listening to hip hop MCs, R & B and rock songwriters. My love of music is its own art form and art practice. The way it shows up in my visual art and poetry is just by-product.

TH: You’ve mentioned a few already, but have you ever had the opportunity to meet and talk with any of your biggest (s)heroes? What was that like?

KF: Absolutely. So many. I mentioned a few already (Giancarlo Esposito, Q-Tip and Phife Dawg, Dove of De La Soul). I also met and interviewed Poor Righteous Teachers at Kent State. I’ve had the opportunity to meet Sonia Sanchez, Lucille Clifton, Wanda Coleman, Greg Tate, Willie Perdomo, Nikki Giovanni. I’ve met a lot of my (s)heroes actually. The most ridiculous one though was seeing Toni Morrison in a theater lobby in New York and deciding to walk up to her and introduce myself to her. It was almost cinematic; me in my Doc Martens climbing over velvet ropes and walking through theatergoers to get to her, and once I did I completely lost the ability to speak coherently. I babbled something about loving her writing, and she just looked at me with the most longsuffering smile on her face and nodded and said thank you. I was literally stuttering. I know she thought, “This poor, pitiful inarticulate child. Bless her, Lord.” But in my defense, what exactly does one say when they stand in the face of a goddess? In hindsight my reaction was pretty appropriate.

TH: What experiences have been most transformative for you in terms of residencies, readings, travel, exhibitions, education, conversations, etc.?

KF: This question is a great one, and to be completely honest with you my entire life has been a series of transformative moments and experiences. I’ve had passing conversations with homeless people that have completely turned my top. I’ve read books that blew my imagination into other realms. I’ve been befriended by some of the most brilliant minds of my generation (to riff off of Ginsberg). I’ve been healed by women laying their hands on me and uttering prayers and poems and incantations. I’ve had men who I thought stepped out the pages of my favorite novels stare me in my eyes and say profound things to me. I’ve been driven to tears in pure ecstasy playing music in my car on the freeway. I’ve had people I deeply respect and admire greet me warmly when they see me in the streets. I’ve had the honor of teaching and working with some of the most powerful artists, writers and activists of this next generation. Some days, the realization that I’m still alive and can find moments to laugh with abandon in this brutal world is a transformative experience to me. The residencies and readings and travels and exhibitions and education are all just icing on a very rich layer cake.

TH: What are a few books and albums that have changed your life?

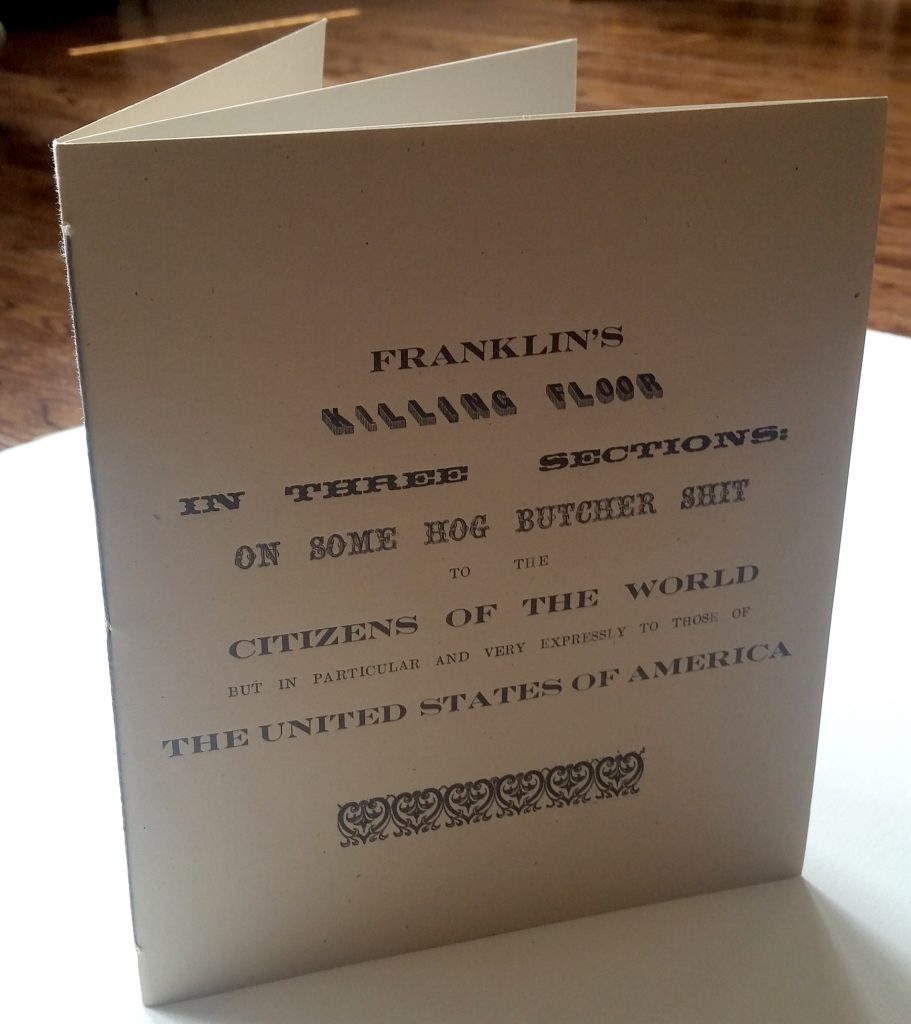

KF: It’s all detailed in “Manifesto, or Ars Poetica #2.” That poem is a roadmap to some of my greatest influences and life changers as an artist, poet, and intellectual. From the opening line (which is an album title) to the lines I sampled throughout it from some of my favorite poets and writers to references to characters in novels to album titles mentioned. It’s all laid out for the careful reader and researcher.

TH: Is there a different pleasure that you find in poetry versus paper and printmaking?

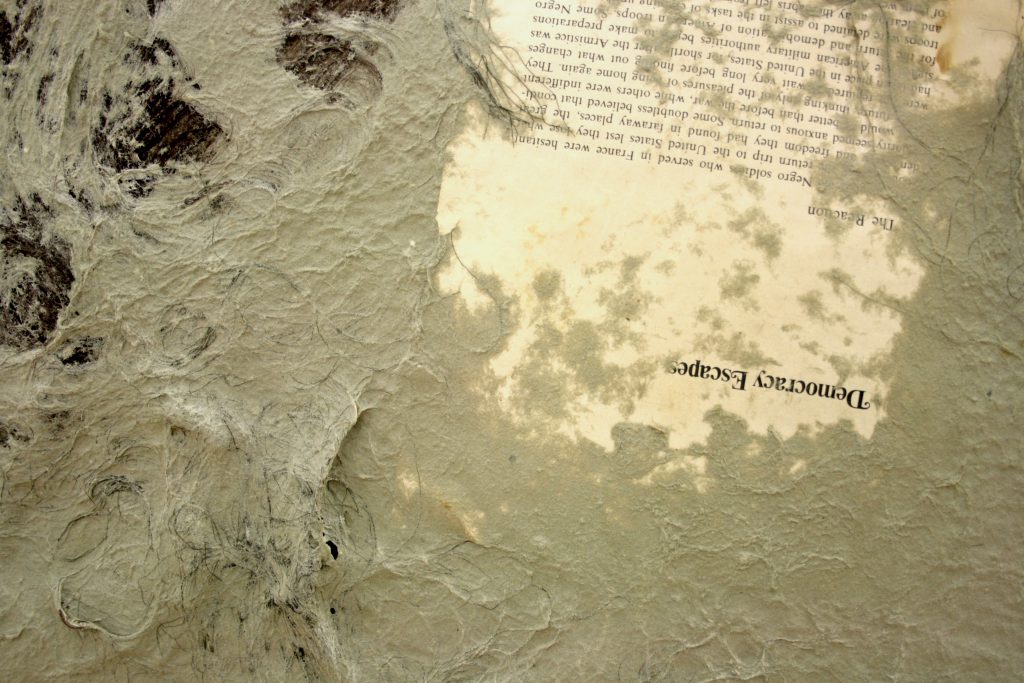

KF: I’ve never really thought about this, but I don’t think so. It’s all labor to me – writing (or constructing) and revising a poem, going through the various steps of the papermaking process, and the letterpress process. The letterpress process for me is more of a communal process because I’m never doing that alone, so maybe there’s a different pleasure in that I’m in community making something collectively. But even with poetry at some point I’m in community sharing what I’ve written so there’s still other people at some point in the game. I think it all comes with a similar pleasure though, or at least from the same life force/source. I will say that papermaking and letterpress are more kinetic to me. I often equate those experiences with dancing, and I often dance when I’m making paper or letterpress pieces. It’s all wonderful though, even when it’s challenging.

TH: How does poetry meet paper? In other words, are there moments when your poetry and your visual art come together?

KF: Very rarely do the two come together. The most obvious example of that would be the limited edition letterpress chapbook, Killing Floor, that I created with April Sheridan and Hannah King in 2015. But even with that project the “guts” were designed by Hannah, and the printing was done by all of us along with Heather R. Buechler. I set the type for the cover and a few of the insert pages, but that was a full-on collaborative effort. I have tried to force my poetry and visual art to play nice with each other, but I don’t think they’re that interested in that right now. I think they’re segregationists.

TH: You’ve already touched on this a bit, but in what ways does your family manifest in or influence your art making?

KF: Oh, my family have always been a huge influence in my writing, and they have appeared in various forms in my poems. The common understanding is that most poets’ first books are about their family. I would probably go so far to say that the first two manuscripts (unpublished) that I wrote and put together were completely about my family and my relationships with them. But when it comes to my art practice in general one has to understand that I come from a working-middle class Midwest family, and work ethic is just par for the course, whether you’re working at a job for someone else or working for yourself and your art. So if there’s any one way they have manifested and/or influenced my art making it’s in the work ethic and the determination for excellence on all fronts. My parents did not find slacking or playing around in my studies and endeavors cute at all. There was a high standard expected of me in all things, and if I was caught slipping there was going to be hell to pay. They conditioned me to be about black excellence, and it was a frequent saying in my parents’ house, “Don’t misrepresent us.” They were about representing before I even heard the term in hip hop. It was not a game to them! So the work ethic is the main family manifestation, but they appear in other forms, both overt and covert.

TH: What are some unexpected or hidden influences on your work?

KF: I’m not sure if there are any, and if there are they are completely hidden from me too. I think most of my influences are pretty transparent or already listed/named. However, there may be some people who don’t know that I’m a serious film lover, that video and the moving image in general have a big influence on my thinking and art practice. I actually find people who leave a movie before the credits have finished rolling to be quite rude. I read film credits like I read album liner notes. I’m always looking for the names behind the images. Many of my good friends laugh at me when I start talking about directors and cinematographers I love and what movies they’ve done, and folks’ filmography. I mean, even with television shows I love I’m like, “Who directed and wrote this episode?” Music videos too. If I see an aesthetic that I love I have to figure out who that is and do all the research. I’m real ridiculous when it comes to that. So there are a number of movie and video directors who are influences on my work, but I’m not sure if their influences can be tied so clearly or directly to what I make or write.

TH: Your influence as an artist radiates not only through your peers and the people in your constellation, but also through teaching, which is something that you are deeply committed to. Where have you taught and why is teaching so important to you?

KF: I’ve taught all over the city of Chicago, but mostly as a poet and teaching artist. Some of the places I’ve taught are Young Chicago Authors, Neighborhood Writing Alliance (now defunct), El Cuarto Año Alternative High School, Art Institute of Chicago, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Gallery 37. There’s actually not too many organizations or institutions in the city of Chicago that I haven’t worked for or with at one point or another over the past 15 years. As far as teaching is concerned, I come from a family of teachers so it’s just a part of the family legacy really. The more I teach the more I’m convinced that I’m in the work of teaching for what I can learn. I say it all the time: I learn far more from the people that I teach, be it children, teenagers or adults, than they learn from me. Teaching is actually a part of my own educational process as a human in the world. I could tell you some kind of altruistic reason for why I teach, but in all honesty my teaching practice is a purely selfish endeavor. I teach to expand my own thinking and knowledge base about the world around me. Almost every group of people I’ve been in a “classroom” with has taught me something new about what I thought I knew, whether they were three years old or seventy-three years old. I’m actually just out here gathering information from all the master teachers through masquerading as a teacher myself.

Learn more about Krista’s work by visiting her website, kristafranklin.com.

Featured Image: Portrait of Krista Franklin taken during a visit with the Art Institute of Chicago’s Teen Lab, November 2016. Photo by RJ Eldridge.

Tempestt Hazel is a curator, writer, and founding editor of Sixty Inches From Center. Her writing has been published in the Support Networks: Chicago Social Practice History Series, Contact Sheet: Light Work Annual, Unfurling: Explorations In Art, Activism and Archiving, on Artslant, as well as various monographs of artists and exhibition catalogues. tempestthazel.com