Viktor lé. Givens‘ work, which is primarily performance, sound, and installation, exists in a continuum of making that is inhabited by writers and storytellers like Toni Morrison and Zora Neale Hurston. The vocabulary used to categorize their style has trouble fully holding them, so what’s required is a new category. One that resembles a recipe kept alive not with precise measurement, but through muscle memory, making, and an awareness of hidden ingredients. Their work is called fiction and speculative, but I resist the limits of those labels. Describing it only as imagination and conjecture doesn’t recognize the knowledge, truth, and undefinable substance that is embedded within it.

In one of my favorite Toni Morrison speeches, The Site of Memory, she pulls the words of Zora Neale Hurston who said, “Like the dead-seeming cold rocks, I have memories within that came out of the material that went to make me.” In other words, there is truth and knowledge to be found in the marrow of our bones. It is a crucial part of how we retrieve and construct our lost and fragmented stories, traditions, and legacies. It is not fiction in the way you may understand it.

Morrison goes on to say:

If writing is thinking and discovery and selection and order and meaning, it is also awe and reverence and mystery and magic. I suppose I could dispense with the last four if I were not so deadly serious about fidelity to the milieu out of which I write and in which my ancestors actually lived. Infidelity to that milieu – the absence of the interior life, the deliberate excising of it from the records […] – is precisely the problem in the discourse that proceeded without us. How I gain access to that interior life is what […] distinguishes my fiction from autobiographical strategies and which also embraces certain autobiographical strategies. It’s a kind of literary archeology: On the basis of some information and a little bit of guesswork, you journey to a site to see what remains were left behind and to reconstruct the world that these remains imply. What makes it fiction is the nature of the imaginative act: my reliance on the […] remains – in addition to recollection, to yield up a kind of a truth.

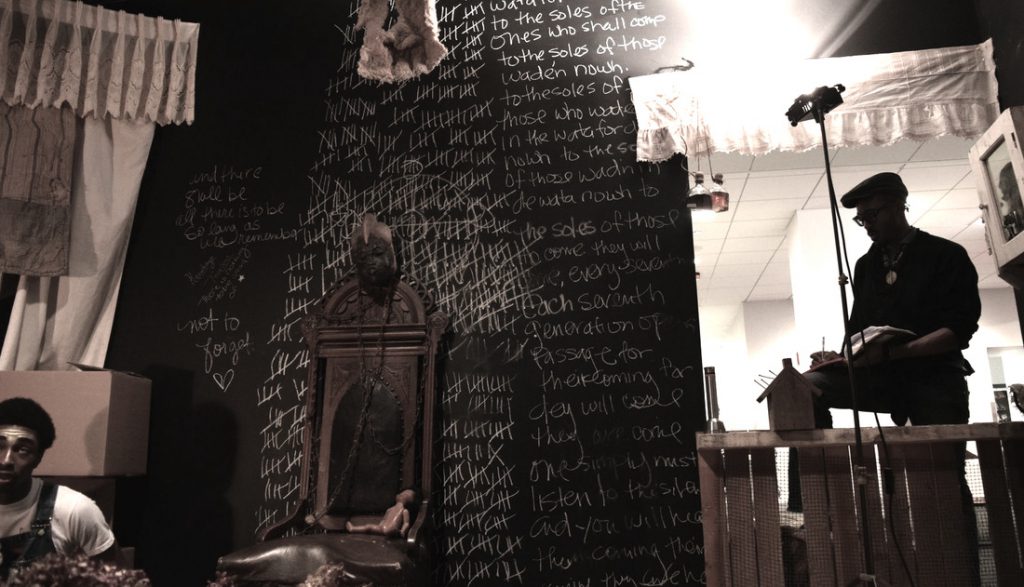

Though the form is different, I believe that lé. Givens’ work is a continuation and adaptation of the methods used by storytellers like Hurston and Morrison who find truth in their bodies and use the whispers of archeological sites (mental and physical) to piece together Black pasts. His most recent exhibition at Rootwork Gallery is an example of this. The In Between Space: Black Magic. Black Manhood. Black Matter is the final chapter of lé. Givens’ series of archeological installations dedicated to Black men with supernatural abilities–the “sight seeing, dream catching, street prophesying alchemists.” It opened at Rootwork Gallery under the curatorial eye of the gallery’s founder, Tracie Hall.

Just as the show was being installed, lé. Givens and I discussed his Texas roots, the often overlooked magic of Black men, and why deep personal excavation became such an important part of his practice.

Tempestt Hazel: Where were you born, where have you lived, and what brought you to Chicago?

Viktor lé. Givens: I was born on an autumnal afternoon in Austin, Texas. I spent my formative years as a child growing up in Houston. Two weeks after graduating high school I moved to Nashville, Tennessee to address my undergraduate quest for knowledge at Fisk University and lived in Ghana, West Africa, Kingston, Jamaica, Washington, D.C. and visited Bahia, Brazil, Gambia, Senegal and Paris, France.

TH: What was one of your most vivid memories of growing up?

VlG: I can recall being in the fifth grade and forgetting to give my father a permission slip needed for a field trip the following day to the zoo. I rummaged through his things until I came across a check with his script and practiced for what seemed like hours to get it even and without reserve.

I guess it goes without saying that I have attended many a field trips since, but this moment struck upon me the realization of the power of illusion and facsimile. I guess it’s when I discovered my magic as an artist.

TH: Tell me about your family…

VlG: I’m the middle child of three brothers. We were close growing up and still are. The three of us discovered, explored, and terrorized the simplicity of being boys and colored in urban America. We often played games made up in spare time and fought until exhaustion consumed us. They called us the brotherly love at the church house where we’d sing praise and worship on Sunday mornings.

I have always been close to my grandmother. She is my link to a nostalgic world from whence my muse is drawn. She is the embodiment of the rural gothic southern south world of dreams and salves, leisure, labor, home economics, blue spirituals, back yard wines, hole in wall social spaces, and open fields. We wrote letters to one another throughout the school year. She was a retired third grade teacher who taught me cooking, sewing, song, and the arrangement of flowers, furniture, and atmosphere in space. As I grew older, these lessons became foundation for my arts practice and to date she is still active in my making.

With my mother there is a sharing of zodiacal and ancestral kinship. Virgos are very ambitious, industrious, sensuous, and nurturing. Performance comes from my mother–that audacity to just be bold and loud, but just as swift into silence and solitude. Mom is very contemplative and thinks thoughts on thoughts thunk. My father is mellow, much like water, he accommodates. He takes on the shape of whatever, however, shifting function to fit form. My mutability and fluid improvisation comes from him. Dad is a dancer. Give him good music and the floor, and he’ll become possessed. He and I make a great pair of muses on the dance floor.

TH: Over the past year you’ve spent quite a bit of time in East Crockett, Texas, as caretaker of your great, great grandfather’s land. What is the story of that land and what role does it play in your work?

VlG: In 1891 my great, great, great grandparents Mary Pain and Albert Burleson gifted twenty acres of land to my great great grandparents Lula Louise and Solomon George Givens as an investment in their union. That following year, Lu and Sol worked towards the acquisition of an additional twenty acres to begin the development of a settlement, known as Givens Hill.

Givens Hill is a what many historians would call a freedom colony. These colonies of freedom were clusters of agrarian, land-owning settlements that were aggressively sought after following the ending of the Civil War. They were often located in secluded regions throughout the South and served as ecosystems for the self sustainability and governance of newly emancipated African families.

Lula and Solomon became the proud parents of seven children: Bertha Lee, Evola Rena, Payne Portilla, Fred Douglass, Mary Etta, Elbert Emory, and Hubert Lawrence. They prospered as social servants and spiritual leaders for migrating Negro families and, subsequently, they leased out the land around them as more families found themselves off the plantations and in territories of their own.

Over time, they developed a large eight bedroom estate where the Givens family resided, a barber parlor, convenient shop , baptismal pool and Men and Women’s social lodges.

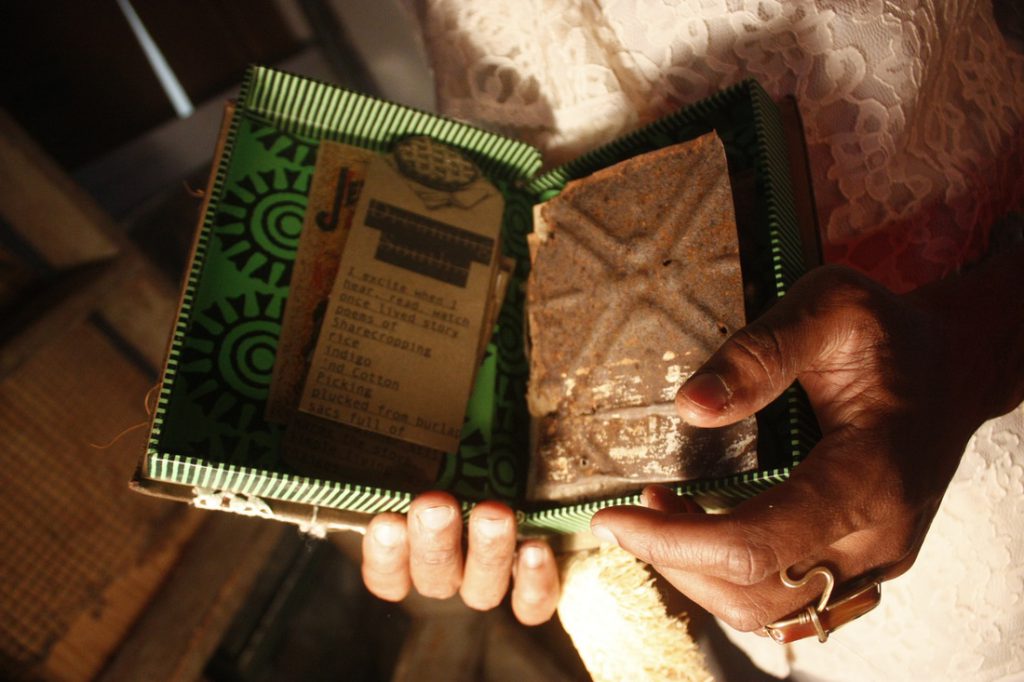

In 1973 an unfortunate fire broke out and consumed the family house, concession store, barbershop, and several other dwellings comprised on the Hill. After the smoke cleared and debris was hauled away there remained a single family home handmade by the men of the family for the eldest daughter Bertha Lee. It is from Bert’s home that I have been able to retrieve and preserve many artifacts from the material lives of my ancestors.

TH: What has the process of restoring the house been like for you and what are your plans for it when you finish?

VlG: It has surely been a process, that is for certain. Of course, there was the initial phase of garnering the support and permission from the elders. I begin rummaging and collecting the objects in the home and because it has been over forty years since it has been occupied, there were a lot of living organisms and excess matter in need of removal. To date, that has been where my energies have been vested–removing the matter, sorting through its content, burning that which was unsalvageable and washing out the home. The site has already be registered as a national landmark. In keeping with the traditions of my ancestors, I want redevelop on the land domestic and recreational spaces for the preservation and observation of creative folk practices.

TH: You work is largely about mining your own history by looking at the lives of your family through different generations. When did you first become curious the lives of your ancestors to the point of knowing you wanted to center your art-making around it?

VlG: I had just finished my first year at Columbia in the Interdisciplinary Book and Paper Arts program back in 2013 and I recall cleaning my studio. I was furious at myself because I saw no clear through line in anything I produced in that year. Nothing. No thing that resonated with me that I should continue to pursue. In that very moment, my grandfather called and said that he needed my help in getting things organized for our family reunion. I agreed to help and he sent me some documents to look over for reproduction. It was a compendium of certificates, receipts, narratives, and photos from the family three generations back. Reading these documents and literally hearing the voices, seeing the visions, and experiencing the emotions felt in the recapitulations let me know that I was onto something. In these archives was source material for a meaningful creative practice.

TH: As you started looking into closets, attics, and hidden places, pulling things out and dusting things off, what objects did you find? Anything unexpected?

VlG: I visited the land where many of the people who this information detailed had lived and started looking around the remaining structures on the lot. I found a few buckets and plant parts. But there was a quilt tucked beneath a window sill in my great great aunt’s bedroom that really got things going. I cleaned the quilt and began sleeping under it, only to be mounted by a series of surreal dreams that led me to archiving and repurposing more of the remaining detritus and travelling to similar sacred spaces in the south. I found myself consumed in the continued excavation, returning every chance I got to the ancestral land to peek around, sit quiet, and listen. That has been the greatest and most unexpected thing I found in the digging–the ability to sit quiet and listen intuitively to the innermost parts of myself in order to navigate the outermost and meet the two (inside and outside) in the middle through improvisation. As a performer, that has been invaluable in the strengthening expansion of my practice. [I’ve developed] an interconnectedness with time, space, and energies to operate within this flow. The initial dreams expressed a need for me to keep looking. As much as this archival work has been about the ephemera of ancestral material culture, it has also opened me up to spiritual, philosophical, and ideological memory as well.

TH: The project that came out of this digging–what is it about?

VlG: The performance installation works that I’ve been developing over the past three years are a result of the digging. It’s a project about neglect, ideas, places, spaces, people, but mostly material matter that aches to be reborn, renewed, regenerated, and re-envisioned. For it will be those things, these revisions and recollections, that will transform places and spaces or people and ideas into something old and new again. This project is about rummage and silence. It’s about contemplation and honesty. It’s about taking desire and motioning through it, following the quiet thunderous beat that tempts us all into trying something different. It’s about sensation and how feeling can lead us to new ideas and how those ideas branch and bloom into complex systems that materialize our outer world. It’s about creative obedience and listening for spaces, matter, energy, and air to speak to all those who take moment to listen. It’s about texture, smell, and surface. It’s about space and how space can speak to a larger psychology. It’s an arrangement being informed by the thoughts and kept secrets hidden in plain sight.

It’s a project about growth, recognition, and the sediments in soil from times before now that nourish the roots of yester-morrow. When we really listen. When we really look. When we really feel. We find ourselves present in another world full of meaning and magic wonder and revelation. Then, the signs within our outer life and in our dreams can speak to us and take us on a journey far beyond our limited world of the ego. They open the door to the symbolic and a world that is just beneath the surface.

Recognizing and working with symbols requires an attitude of receptivity that allows the symbols to communicate their own language. And it is from this inner world that our everyday life is nourished and we are given the direction we need. We are given joy to counter a culture that so eloquently loves to rob us of our being. Each of us has our own journey to make, our own exploration of the inner world, and we are drawn into this dimension through different doorway: dream work, music, painting, sacred dance or just sitting and being present with images that arise from the depths. Each journey will connect us not only to the meaning and purpose of our souls as individual bodies, but as universal energy bodies as well.

TH: In what ways do you better understand yourself since beginning this archaeological and historical digging that you do?

VlG: It’s surely softened my heart in a way that allows me to be open to receive what messages, memory and matter is wanting from me at the time.

TH: Much of the history, ritual, and practices your work taps into is rooted in many different geographies, but as an artist, you are invited to present it in many different spaces–each with different audiences and different levels of cellular understanding of what you do. I’m thinking specifically about the context of a MFA program, like the one you are wrapping up at Columbia College, or when you do work outdoors, in structures you’ve had a hand in sustaining, or places like Rootwork Gallery. How do you adapt your work to different contexts?

VlG: That’s the beautiful thing about working in the intuitive–it takes you where it wants to go. I am not one for aggressive marketing and administration for the work. I allow spaces, people, commissions, and workshops to come to me and I respond accordingly. Operating from that framework allows for an immediate filter to happen whether or not the space or people are open to receiving the work. I have learned that Western academic settings are archaically logic-centered spaces. Discourse around the emotive, intuitive, or spirit consciousness really makes the academic world uncomfortable and awkward. So what I have learned to do is covert shaman syncretic work, which directly/indirectly addresses the same needs without the explicit language around it. I am coming to find that this is the tactic employed by my ancestors before me when cultivating traditional consciousness under colonial surveillance.

TH: The upcoming exhibition at Rootwork Gallery is the final chapter of a four-chapter series you’ve created over the year. Can you talk a bit about the first three chapters that are leading up to this final one?

VlG: Surely. Back in 2013, shortly after the family reunion and series of dream sequences, I was invited by Heather I. Robinson, the director of the South Side Community Art Center at the time, to participate in a incubating residency in Gallery Too. It was during that time that the Dreaming South Suite was born. I took the initial collection of objects archived from the family estate and installed them in a spatial dream and improvised a performance ritual that has been archived as an experimental short film.

Then, that following spring, I was approached by Felicia Holman who was curating an exhibition on community collaborative works called CONNECT/ENGAGE at Columbia College. For that exhibition, I facilitated my first creative arts performance workshop for artists working with ancestry and memory based on Dreaming South Suite.

[The third chapter came when] I was awarded a three week residency with the Department of Exhibition and Performance Spaces (DEPS). The residency ended in the exhibition In Search of My Familiar: Dreaming South at C33 Gallery.

TH: For this series, you call out writers Charles Chesnutt and Richard Wright as inspirations. What is it about their work that resonates with the ideas embedded in your work?

VlG: I have always been drawn to recalled stories around spiritual encounters or experiences, but as I began to do more research on the folk customs of the African diaspora, I found that there was a progressive silence happening in the mentioning of black men in relation to this magic and in relation to his active participation in the preservation and evolution of traditional consciousness. I could find documentation of the black male in the black church, but not much on black men who operated outside the colonial mainstream. That got me to thinking about The Man Who Lived Underground by Richard Wright, which is the story of Fred Daniels, a black man who fled false accusation by taking shelter in the dark and quiet recesses of society. While in that blackness and in that dark, he has a cathartic revelation and aches to share that with the people above ground. Instead [of sharing his revelation, he is] shot to “keep him from causing trouble”. And although some may read that work and assume that he died after being shot, I like to imagine that he didn’t die, but was taken even deeper into the dark and we haven’t seen or heard from him since.

As for Charles Chesnutt, it was in his compilation of Conjure Tales that I was able to see the presence of the black male as protagonists, antagonists and narrator in memories of black men in relation to magic. His stories make me wonder what we might gain from expanding discourse around black male development through the inclusion of magic and the intuitive in that discussion.

TH: During your research, did you find any reasons behind why men are so few and far between in this history and these discussions?

VlG: It’s simple. Black men are powerful with or without magic. And I must clarify that my use of the term magic isn’t in the Walt Disney animated graphic sort of posture. Rather, magic is a conscious/unconscious knowing and exploration of the intimate connection ‘tween, matter, mind, improvisation and the phenomenology of being.

It goes without saying that western colonies both of the ancient past and the immediate present are/were designed in an attempts to control and regulate people and resources. Conjure, root working, folk belief, and magic all operate in such a way that they become explicit, culturally specific ways of thinking and talking about cause, effect, power, and agency. They are practical, creative processes of mobilizing spiritual and material resources to address problems and to effect change.

So, quite naturally, if colonies are designed for control and control is designed to take away agency, then there can be no mention of black men and their magic. We can find evidence throughout the visual culture of this country of strategic campaigns assaulting and muting the voice of the black males’ execution of magic. Now, I am learning as I explore the narratives, archives, and material culture of the south that simply because a thing is not mentioned does not mean that thing does not exist. As Zora Neale Hurston says in Mules and Men, “Nobody knows for sure how many thousands in America are warmed by the fire of hoodoo, because the worship is bound in secrecy.”

The navigation of being a black man in a colony designed for oppression places his execution of magical agency in an interesting position of vulnerability. He either uses his magic and suffers exploitation or assassination, or he becomes so enlightened that his dealings with the mundane become distracting and he vanishes into the “wilderness”. I am interested in the brothas that exist in the middle place ‘tween the dead and the vanished. How are they coping and dealing with their abilities? In a society so hard wired in the logical and empirical, where do my brothas go to strengthen, hone, and cultivate their magic? Then again, such worship is bound to secrecy–right, Zora?

TH: After experiencing your work, what do you hope that people walk away with?

VlG: Memory and encouragement to keep going inside the work, inside of life.

For more of Viktor’s work, visit his website, southernandroid.com.

The In Between Space: Black Magic. Black Manhood. Black Matter. runs through November 12, 2016 at Rootwork Gallery (645 W 18th Street). The gallery is open by appointment.

Featured Image: Portrait of Viktor lé. Givens in front of Rootwork Gallery prior to the opening of The In Between Space, September 9, 2016. Photo by Janelle Vaughn Dowell.

Tempestt Hazel is a curator, writer, and founding editor of Sixty Inches From Center. Her writing has been published in the Support Networks: Chicago Social Practice History Series, Contact Sheet: Light Work Annual, Unfurling: Explorations In Art, Activism and Archiving, on Artslant, as well as various monographs of artists and exhibition catalogues. tempestthazel.com

Tempestt Hazel is a curator, writer, and founding editor of Sixty Inches From Center. Her writing has been published in the Support Networks: Chicago Social Practice History Series, Contact Sheet: Light Work Annual, Unfurling: Explorations In Art, Activism and Archiving, on Artslant, as well as various monographs of artists and exhibition catalogues. tempestthazel.com