Without, Within the World: The Dojo

Call them DIY, alternative, radical, or safe, Chicago’s independent art spaces create a world without money and borders within a world defined by both. They function as community hubs and…

Call them DIY, alternative, radical, or safe, Chicago’s independent art spaces create a world without money and borders within a world defined by both. They function as community hubs and communal living spaces, providing free and affordable entertainment, hosting activism workshops and food drives, and building connections among young, emerging, and marginalized artists. “Without, Within the World” is a series of interviews that asks curators and administrators about building utopia while maintaining viable spaces.

The first to be profiled is the Dojo, an underground performance venue and gallery in Pilsen. Though the Dojo has its roots in the DIY music scene, their curation constantly skirts the boundaries between genres and communities. Established in 2015 by Alex Palma, Mykele Deville, and Daniel Kyri (DK), who all lived in Pilsen at the time, the Dojo is now run by Palma and Calie Ramone, who work with a variety of outside curators and “Dojo Homies,” who put together diverse music and art shows two or three times a week.

When I meet Palma at his Pilsen apartment (he recently moved out of the Dojo), he immediately ushers me over to his living room closet to show off the cat shelter he has just finished constructing. Five newborn kittens huddle together on a blanket in the warmly lit (and warm) paradise he has created for them—complete with a neon palm tree. Outside of paradise, three adult cats roam the living room, and Palma hands me a broom to ward off attacks from the paternal feline. This is just what Palma does. When I ask if he has an ego about his work, Palma reminds me that as an A/V technician, he is trained in service. He sees systems and how to build them, which results in a methodical, interdisciplinary, and collaborative working process that has marked the Dojo.

A portrait of Alex Palma, a co-founder and curator of the Dojo. He stands next to a string of lights wearing a dark jacket, a multicolored scarf, and black glasses. Photo by William Camargo.

Sasha Tycko: So the Dojo recently celebrated two years with an all-out festival at ChiTown Futbol, but you initially imagined it as more of a collaborative work space?

Alex Palma: The thing about the Dojo is that there’s no real plan for it. It’s just like each person who is involved is doing their own thing and everyone just works together. When I first got there, I was not anticipating doing what we’re doing. I’m more into post-production and quiet work, especially at the time, not events, so I had an idea of making it more like a home studio kind of thing. Which of course would ironically just lead to working in isolation. But Mykele and DK know half of Chicago and probably know two-thirds of Chicago now. Mykele immediately brought the DIY scene to the space, whereas DK and I had no concept of what the DIY scene was at the time, and all of the sudden we’re a part of it. By DIY scene I mean various houses and unofficial venues that operate and throw shows in their home. We kind of picked up the model from them. I don’t think we would have done things any way similar or even be called DIY if we didn’t start with the DIY scene, as in they were part of our audience. The short version of that is that we ended up saving a show, because a show fell through somewhere else. I don’t think my Dojo would have been DIY, especially since at the time I had a higher level of production value that I wanted to do. But it’s funny, because ever since, it’s been all about lowering the production value bar in order to make it easy and financially feasible.

ST: Can you give a picture of how the Dojo operates?

AP: It operates very differently now than it did.

ST: Feel free to give that story. I’m wondering how it remains sustainable while also paying the artists who perform there, and how you curate shows and decide who to work with.

AP: Basically, the core model of it is that it’s a home, it’s a live-work space, so people pay rent to live there. We don’t do it like some other DIY venues, which throw shows to pay rent. The Dojo is not responsible for covering any of the roommates rent. So, they live there, and we do our own events and bring in other people’s events. The function of that is that you can pay the music artists, because you’re not trying to cover your own rent. That’s how it started. Since then, our rent has been hiked several times, and the way we wrote it in is that it’s the Dojo’s responsibility to cover the rent that’s been raised since we started operating a DIY venue.

We also run a gallery from time to time. In the first year, we started with a strong visual gallery, but we’re more of a music space than a gallery. We don’t charge a hang fee. We do the $5 suggested donation at the door, and that’s how it works. We also have installations. The principle Dojo show, with all the core elements, has some sort of live lit, spoken word, poetry, open mic sort of thing; you have music performances in the basement and you probably also have a DJ in there; you have a gallery and an installation artist, and then you have someone cooking in the kitchen.

Alex Palma sits in the installation room of The Dojo, which became the “Self-Care Room” at the previous night’s fundraiser event for Mexico and Puerto Rico disaster relief. On display is a bouquet of flowers surrounded by an assembly of mirrors that lean on a black chalkboard wall. Photo by William Camargo.

ST: That’s what initially impressed me so much about the Dojo, and I’m guessing for other people, too—the complex format and how interdisciplinary it was. There’s so much more going on than a typical music show or gallery event.

AP: Yeah, we’ve gotten more music people interested in visual art for that reason.

ST: I don’t want to say that there wasn’t anyone else doing this at all, but it felt like something new and exciting to me, coming out of the DIY music scene.

AP: That’s the thing. We started existing in a scene. There are so many people who run spaces who would never call themselves DIY, they’re just different communities. We started within a very explicit, rock-oriented basement show scene.

A view from inside the Dojo installation room, which occasionally doubles as a bedroom. The open doors display a sign that says “Please respect the space!” and look out on a hallway decorated by a collage of posters and prints. Photo by William Camargo.

ST: Another thing that I think is unique about the Dojo is how much you bring in other people to curate shows. What’s your criteria for collaboration?

AP: We mostly bring in people who are looking to put on whole shows that are more conceptually oriented. Our first year was really focused on throwing our own shows and showing people you can use this specific space to do very cool things. So these first two years grinding out shows has led to us getting tons of proposals and handpicking the best proposals that utilize the space in cool ways and work with specific communities. For a lot of people, it’s their first or second show, so we do a lot of hand-holding. We intentionally try to reach different communities, and communities we haven’t worked with before to keep it this diverse, multicultural space. The people who go to the punk shows here won’t necessarily go for the dance party shows, or the more experimental music or poetry events. So they’ll think it’s the place that punk shows happen at, or whatever it is they’ve been to. The cool work for us is to try to cross-pollinate. The DIY scene is always there.

ST: What do you mean by that? That the DIY scene is always there.

AP: I don’t know how you feel about this, but when we say the DIY scene, it’s really just a specific community just like any other community. DIY [“Do-It-Yourself”] is a way of working, but when we say DIY scene we’re talking about the people that go to DIY shows, which is a specific crowd. Also, I feel like everyone has a different crowd for that because you frequent different spaces. It depends on genre, but within the Latin music scene there are so many people putting together shows in different kinds of spaces, but I wouldn’t consider them “DIY people.”

ST: I’m mostly coming from the DIY scene myself, so I don’t have the full perspective on other scenes. DIY stands out to me as a scene that has a pretty solid infrastructure that outlasts the specific people who come in and out of it, and that’s why it’s “always there.” It’s basically a network of physical alternative spaces, and even a national or international network. I don’t want to say other communities don’t have infrastructure, because that’s just not true, but there’s something very concrete about DIY.

AP: And the people who hold space are the people who primarily hold the infrastructure together. So if you run a space, or are in a band with people who run a space, that’s the scene. And if the spaces work together, it’s a community. By work together, I mean they recognize each other and support each other and pass artists on to each other. Which is what we’ve always done between a handful of spaces. There are obviously lots of DIY spaces that don’t all clump together, which is basically because of genre or identities. I don’t think it’s necessarily prejudice, it’s more just based on interest; so the DIY scene is made up of people interested in being in alternative spaces.

In the storefront gallery of the Dojo, a DIY Townhall hosted by the sexual violence-prevention collective F12 Network has just wrapped up. A circle of folding chairs fills the room, with art by Xavier Robles, Claudia Palacios, and Verónica Giraldo hung on the walls. Photo by William Camargo.

ST: What’s a show you’re especially proud of?

AP: The show I’m most proud of is the first time we had a Latin music showcase at the spot, which was probably the first show I curated myself. This was almost a year after we started. It was called Latinx World, which was basically doing a Latinx music show in the context of the DIY scene. We explicitly invited more people that identify as Latino, Latina, or Latinx from the DIY scene to participate in something with folks that have nothing to do with the DIY scene. I think it helped the DIY scene be a little more aware of the Latinx communities and culture that a lot of our DIY scenes are operating within, which is the big thing, because most of these venues are in Latino neighborhoods and typically aren’t that inclusive of those communities. The aside to that is a lot of punk houses seem to be more integrated into the Latino communities and neighborhoods than the more interdisciplinary DIY spaces seemed to be at that time.

Those of us who put on shows in the space kind of use our own identities to throw shows, and since I hadn’t really started curating until a year into it, there wasn’t really representation of Latin music. Of course, you can reach across cultures and identities, but it’s not as likely to become part of the structure. So that became a series, a Latinx World series. Lester Rey put that together with me, and got most of the lineup together. That was sort of the access point to Latinx music, and I asked him to throw more shows at our space. So we did three shows under that name [Latinx World] and another three under a different name [Dojo Presenta]. Since that got moving, the space became welcoming to Chicano folks, Puerto Rican folks, and they started hitting us up for shows. We also started to have dialogues that pertain to gentrification, which in that first year were not existent.

From the previous night’s fundraiser event for Mexico and Puerto Rico disaster relief, a sign by organizer Chrissy Puga reads “palante mi gente,” flanked by bouquets of flowers with a string of lights above it. Photo by William Camargo.

ST: Along that vein, what kinds of conflicts in the space or criticisms about the space have come up, and how have you dealt with them?

AP: The people who run alternative spaces tend to have stronger ideologies than more official, licensed, or commercial venues. We’re claiming to be an accountable space, so we have to be held accountable. This scene and these spaces have two problems, in general. One is sexual harassment, and the second is gentrification. They intersect a little bit, but basically these are two big storm clouds over DIY and alternative spaces. These are problems happening all over the country and in our scenes, but being alternative spaces, we want to be proactive and try to do something about it.

ST: Is there a protocol you have for handling sexual harassment, either in your space or related to the people you book?

AP: Everything is case by case. We’re fortunate enough to have worked pretty hard in the first six months or so to maintain a respectful culture at our space. It took the strong, hard work of Mykele and DK and those folks. Now, we have enough name recognition that the space holds it for itself. You’re going to harm your own reputation if you do some shit at the Dojo, and people know that. We’ve been able to change the norm. There is harassment that happens, but we haven’t had to bounce people in a while. That can happen. We tend to oversaturate the shows with artists and volunteers that there are enough people representing the space and subtly dictating how you’re supposed to act there.

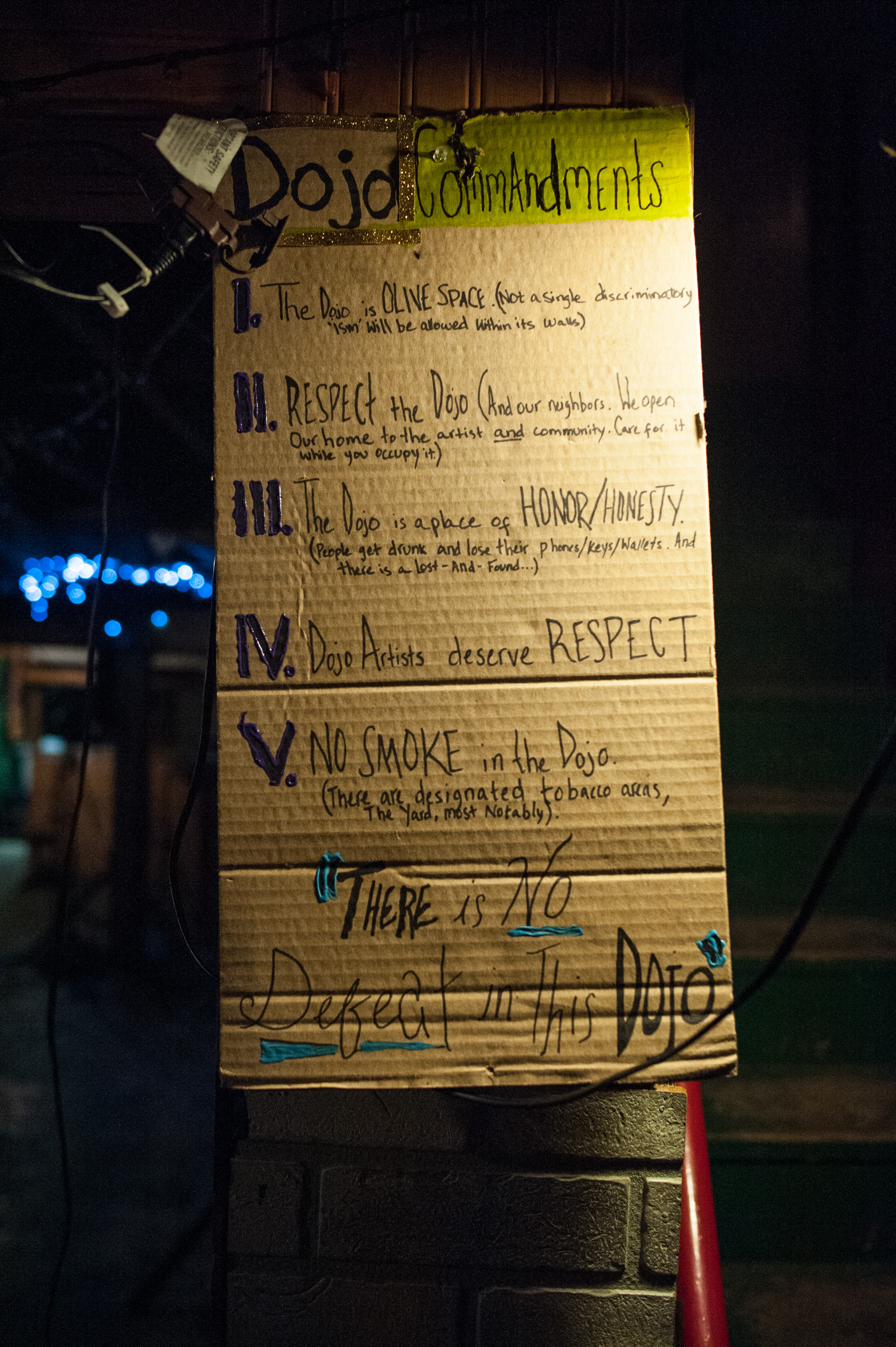

ST: You have a lot of constant communication happening between the space and the people there, with signs on the walls, extensive messaging in Facebook events, and the way you greet people at the door.

AP: Right, it’s very direct. We’re building policy that’s more strict for using the space as a platform for artists and not trying to support artists who have a history of abuse; which is borderline shunning people, so it’s sticky. We’re working on it.

A sheet of cardboard displays the “Dojo Commandments,” with the space’s motto, “There is no defeat in this Dojo.” Photo by William Camargo.

ST: So how are you thinking about the problems of gentrification and what people call “art-washing?”

AP: A lot of these DIY spaces are traditionally white-operated, and a lot of them are run by post-college people and transplants to the city, etc. So basically, people who are not from the specific neighborhood who are holding space in the neighborhood. The thing that’s nice about DIY is that they’re typically very quiet and under the radar, so I like to think we’re not causing as much of a problem in terms of facilitating gentrification as opposed to a coffee shop that pops up in Little Village or Bowtruss [in Pilsen], where immediately you have neighborhood people tagging your building and telling you to get out.

ST: Of course, there’s also the piece about coffee shops being for-profit.

AP: That’s true, but I’m just talking about the visuals of holding space in a neighborhood. Because it’s a home and alternative space, we have no interest in putting a sign in front of our house. That puts us in a different kind of space than other ones are in. It’s a very sticky space where people will hate you or they’ll love you. A friend said to me that art can basically either be a lubrication for gentrification, or it can resist it—by cultural preservation, specific fundraising, or helping educate folks that aren’t aware of what’s going on.

People have different policies. The Defend Boyle Heights movement out west has a very strong way of combating gentrification, which is arguably a way that works. In that model, if you’re soft against gentrification you’re facilitating it, which is messy and basically means you’re not supposed to facilitate anyone that’s not from the community. They didn’t say that, but the more that I think about it, that’s what it means. They have a philosophy that might be different than our local philosophy. I think if we showed up in Boyle Heights, we would have been shut down immediately, maybe. The only thing that could be the Dojo’s saving grace in terms of not facilitating gentrification is that we have no intention of ever becoming a legit business, so we can potentially exist as a place in Chicago that can facilitate people from all over the city and not be so attached to the neighborhood. We have a very small physical presence. Our name is very much attached to Pilsen, which is probably the most damage we’ve done because we make Pilsen look hot, which attracts developers and gets everything steamrolled. I’ve been thinking about this a lot, and I don’t know how to sum it up yet.

The basement walls of the Dojo are covered by murals and art by various Chicago artists. On this wall, a Mexican flag with faces drawn on by Javier Suarez partially covers a figure painted by Ross in black-and-white, who asks, “Who You Looking Up To?” Photo by William Camargo.

ST: Do you need to take a breath? I can pick up on something I think you’re saying, that the specific DIY model you operate with is not for profit, but not a government-recognized nonprofit, which means there’s something inherently anti-state and anti-capitalist about it.

AP: Yeah, but also in operating that way you can inadvertently attract developers. And because a lot of DIY venues that call themselves DIY are operated by mostly white people, they get less flak from the police or government for operating illegitimate music venues. It’s a double standard that allows DIY to exist, even though it’s unregulated.

ST: Right. DIY is not heavily policed.

AP: The other thing is there’s a variety of underground functions that aren’t DIY at all, but are just the way a specific community is working. There’s just so many private spaces that operate as public spaces, especially in Latino communities. DIY has a thing about naming itself. It’s funny. The problem with that is it leads into a colonial consciousness, where it’s all about the idea that what I’m doing is special.

On another basement wall, a swirl of colors makes up a painting by Shira Stonehill titled “New Mexico.” To its right, Tattianna Howard’s painting of a figure whose braids float toward the sky pays tribute to Jamila Woods’ “Holy” music video. Photo by William Camargo.

ST: Within Pilsen, you’re intentionally working with specific community organizations. Can you talk about some of those collaborations?

AP: We work with some neighborhood groups, such as Pilsen Alliance and ChiResist, and all that we simply do is provide space for them because they asked for it, which is a good way to be an ally. Keep in mind we don’t actually have that many resources. We’re just a house that throws shows; but by making others feel welcome to the space, we provide a resource that is free and maybe more available than other spaces in the neighborhood. I think one thing we can do as a space is help the people who feel threatened by gentrification communicate with the gentrifiers. We prioritize those activist organizations. I don’t know if this has to do with gentrification necessarily, or just supporting Latino communities in general, if you support a Latino cause. They’re kind of separate issues.

Gentrification is all about the quiet, slow, unconscious attack. I’m half-white, too, and sure we’re not literally raiding communities, but the colonial thing is still there in our actions. Also, sometimes more pressing issues come up around the country. So when the hurricane hit Puerto Rico or with the series of earthquakes in Mexico, we’re a good resource. We can hold fundraisers really easily. We’re super welcoming to those events, and that’s helped us assist our local community overall, rather than cause problems around gentrification. That’s an interesting situation, because it sort of means there’s bigger fish to fry than gentrification, and we can be allies with that.

Featured image: The basement stage of The Dojo, a DIY venue in the Pilsen neighborhood that provides space for emerging and marginalized artists and organizations. The floor-level stage is covered by a red throw rug and lit by lights strung from the ceiling. An acoustic guitar is propped up next to speakers painted by artist Presley Joy Paget. Photo by William Camargo.

Starting from the proposition that art-making is world-making, Sasha Tycko combines community organizing and curatorial work with writing, music, and performance. Tycko is a founding editor of The Sick Muse zine and an administrator of the F12 Network, a DIY collective that addresses sexual violence in arts communities. Find more on IG: @t_cko and at www.nomoneynoborders.com. Photo by Julia Dratel.

Starting from the proposition that art-making is world-making, Sasha Tycko combines community organizing and curatorial work with writing, music, and performance. Tycko is a founding editor of The Sick Muse zine and an administrator of the F12 Network, a DIY collective that addresses sexual violence in arts communities. Find more on IG: @t_cko and at www.nomoneynoborders.com. Photo by Julia Dratel.