Trouble At Mill Hill: An Interview with Samantha Hill and Ed Woodham

An interview about their experience at Mill Hill and being asked to leave for questioning the ethics of the residency’s approach to social practice.

This interview informed the essay, The Impossibility of Art, which further contextualizes and digs deeper into the concerns brought up by artists Samantha Hill and Ed Woodham during their work at Mill Hill. Read the essay here.

Maya Mackrandilal: In your practice, collaborating with communities has been central to your methodology. Before we delve into what happened at Mill Hill, can you tell us a little bit about a successful “social practice” project that you executed with the support of an institution? In particular, what structures (in your experience) are important to have in place in order to ensure that communities are not exploited or harmed by this type of work?

Samantha Hill: The most successful social practice project that I executed with the support of an institution was projects for the RISK exhibition at Columbia College curated by Amy Mooney and Neysa Page-Lieberman in collaboration with Allison Peters-Quinn from the Hyde Park Art Center. The purpose of this exhibition was to highlight artists that collaborate with individuals and communities to develop projects to activate neighborhoods in Chicago. During this time, I was working closely with the Bronzeville community organizations. So, I thought participating in RISK would be a great opportunity to collaborate with organizations, like the Bronzeville Historical Society, whose mission is to cultivate cultural & educational enrichment projects in their neighborhood.

The RISK curators understood and respected the ideas of the artists and community collaborators involved in the exhibition. We received all types of support from them, including planning meetings, funding, studio spaces and access to equipment to construct the projects.

An important aspect of my work is to have active collaborations with community organizations when creating art. They are the gatekeepers of their neighborhood and work diligently to develop programming which empowers the community. My role as an artist is to listen and learn from these organizations so I can present creative ideas during our brainstorming sessions. The community organization is constantly consulted during the planning process to make sure that our art project represents their story in an authentic way.

Ed Woodham: I recently completed a year long commission which transformed into a residency as part of Jamaica FLUX 2016 co-curated by Heng-Gil Han and Kalia Brooks at the Jamaica Center for Arts and Learning (JCAL) in Queens, New York. It began with a tour of the facility of the 100-year-old building which led to the discovery of the basement which was full of many years of collected debris floor to ceiling. “This is prime real estate for artists’ studios”, I told the executive director, Cathy Hung.

Hung together with curators Han and Brooks facilitated a path for my project to develop organically as I slowly but gently embedded myself into the JCAL institution. They introduced me to staff, the board president, and members of the JCAL and Jamaica Queens community who provided resources and encouragement but also questions, scrutiny, and numerous discussions.

At the beginning of the residency, I created a survey (eventually narrowed to ten questions) that was distributed to the Jamaica Arts and Learning Center staff, board, mailing list, and general public about how the center could best serve the needs of the community. The JCAL staff were vital participants in creating the questions on the survey as well as essential in the distribution throughout the community. The cleaning of the JCAL basement – was a long arduous process of group discussions, organization, collaboration, patience, sorting, cleaning, and removal of debris to bring to order and to make space for artists’ studios. Two 30 yard dumpsters were filled with detritus from the basement. Four artists are currently working in the newly created studios in the basement – with a social justice arts residency in the research + planning stages.

My relationship with both the basement and JCAL was less institutional critique but more maintenance of an institutional space underused and under-imagined. During the process of the residency there were discussions and mutual critiques of our respective priorities and focus – often difficult and frustrating for everyone. The residency project was successful because of the inclusion of diverse community voices and the deep commitment and investment of all parties.

Regarding structure to have in place to ensure that a community is not exploited: sound ethics and a solid history of authenticity in producing socially engaged projects in communities by the sponsoring organization.

MM: Are there any resources (particular theorists, critics, or artists) that helped you establish your own personal definition of an ethical social practice?

SH: Although I have read texts from theorists and critics such as Tom Finkelpearl, my biggest influence for developing my own definition of an ethical social practice originates from my Father. My Father was a teacher and developed sports programing in his childhood neighborhood of North Philadelphia. North Philly was a blighted area during the 80’s and he worked with a variety of community groups to develop programming in the area. This work was more than a job for him, but a way to share his gifts with youth to inspire their personal empowerment. I learned how to listen to a community’s ideas and needs by watching my father collaborate with educators as well as residents in the neighborhood. I have incorporated his lessons into my practice when developing community engagement projects.

Flyer posted in Fort Hill by Danny D. Glover. (Image courtesy of the artists.)

EW: I have family, friends, artists, and non-artists* who I hold in high esteem for their integrity –who’ve taught me through either their body of work and/or their life actions. My art practice is an ongoing exploration of working with public space, communities, artists, and institutions – and often there are mistakes. I don’t hold myself up to be a model of social practice ethics. Through my work in communities, I am continually investigating the elements of holistic ethics. I credit not being complicit to social injustices to my family upbringing and my collected life experiences as a queer growing up in the segregated South in the 1960s +70s. Models for me are most often personal rather than theoretical: Linda Mary Montano is a friend and mentor. She embodies ‘Art = Life’ through her work with personal and spiritual transformation.

MM: How did you find out about the Mill Hill Artist Residency? Why did you apply? What were your goals for the residency?

SH: A friend emailed me the listing for the residency because the call asked for artist working on neighborhood projects based on a community’s history. She thought it sounded perfect for me. I reviewed articles about Mill Hill and the Macon Roving Listeners, a community group that listen to the stories of their neighbors as a way to develop connections within their community. As a story collector, I was excited by the possibility of collaborating with a story collector community group to develop an installation project about the history of their neighborhood.

EW: I found out about the residency from Terry Hardy, an Atlanta friend and artist. I applied because I’m from Georgia originally and have been away for 20+ years. I was excited to hear of a social practice residency 45 minutes from my hometown of McDonough, Georgia. It was a rare opportunity for me to bring my experience of working with communities back home again. I was excited to live in a cottage in East Macon, have a studio, explore the geography of this new place, work alongside fellow artist Samantha Hill to see her process, research East Macon + Macon history, and get to know East Macon residents and Macon artists. My hope was to empower the spirit of both the residents and the arts community by conceptualizing and creating art together.

MM: Before arriving in Macon, did you encounter any “red flags” within the Macon Arts Alliance that would hint at their problematic relationship with the community? Are there any questions you wish you had asked ahead of time?

SH: I asked Jonathan Harwell-Dye a variety of questions about how community groups were engaging the neighborhood. Harwell-Dye told me about the Macon Roving Listeners story collection project and how they were making connections within the community through community dinners. Dye also mentioned they were in a process of developing a community land trust to keep the residents in the neighborhood. He had positive answers to my questions, so I thought the MAA had a good working relationship with the community.

I wished I would’ve asked to connect with other African American community organizations besides people on the Mill Hill Steerage Committee before the residency so I could hear a different point of view from people not working with the MAA.

EW: I called Jonathan Harwell-Dye with a list of questions before I applied to the call for artists. He answered every question beyond my expectations with answers that got me very excited with the anticipation of really wanting to be selected for this open call. He told me about 1) how the entire community had been engaged from the onset for two years, 2) that members of the community were on the steering committee, 3) about the Roving Listeners collecting stories, assets, and gifts (talents) from door to door interviews of residents, 4) about the Land Trust to ensure that no one would be displaced 5) about the cottages that the resident artists would be housed in within the community during the residency. Everything seemed to be in a genuine place for an ethical socially engaged community residency to create art with the designated residents and local artists.

I wish I had asked:

- Have there been any objections from the East Macon/Ft Hill community about Mill Hill Arts Village?

- How many African American exhibits have there been at Macon Arts Alliance gallery?

- Have other predominately African American communities in Macon been revitalized and what is their current racial make-up?

MM: Did you two have any communication before arriving in Macon? Were your projects aligned in any way?

SH: Yes, I was in communication with Ed before arriving in Macon. We spoke about our past works and ideas we would like to explore in our individual projects. I was interested in learning more about Ed process in developing projects in public space. The goal of this residency was for Ed and I to make separate projects, but we were both excited to learn new skills from each other to support our individual practices.

EW: On April 1, Samantha and I began conversations to re-write the contract that was originally emailed to us. Our original contract exclusively protected the MAA. It had no provisions that protected us – the resident artists – from artistic license to our mutual contractual rights and well being. We thought this was odd especially for a ‘social practice’ residency but we decided to be patient since it was the MAA’s first attempt. And they complied with almost all of our re-writes.

Our respective practices are very different. I was interested in learning about Samantha’s practice and interview methodology. Since I am Caucasian (and the community is African American) I planned to listen to a wide spectrum of the residents for a long period of time before conceptualizing an idea with the community + local artists.

MM: How long were you in Macon before you started questioning the purpose of the residency and the mission of the Macon Arts Alliance? What were some initial signs that “art-washing” was taking place?

SH: The first moment I began questioning the purpose of the residency when I met an East Macon artist who gave me a tour of Mill Hill and the surrounding neighborhood. He shared with me the community’s concerns of being displaced from their homes. Also, he told me that many people connected to the African American arts and grassroots communities are excluded from projects and exhibitions supported by the MAA. These concerns of exclusion were repeated to me by other marginalized artists in Macon.

EW: I fortuitously met an artist who had grown up in East Macon on the third day of the residency who drove me through the neighborhood and revealed his feelings of discomfort (and other community members) of the Mill Hill project being thrust onto the neighborhood and his feelings (and other African American artists) of being marginalized by the Macon Arts Alliance.

Signs of ‘art washing’ or disingenuousness came from the MAA being noticeably irritated as we asked for contacts in the African American community, as we decided to not exclusively work with the Macon Roving Listeners (who were obviously following a script), and as we strayed (as any good social practice artists would do) from their framed report of the neighborhood.

MM: Is there a specific story from a community member that you are able to share that can help illustrate “art-washing?

EW: After we were terminated, Samantha and I returned to Macon for a community-wide meeting addressing issues we had surfaced. The artist (mentioned above) who had been our community contact since our third day in Macon stood up to introduce a renter on Schell Avenue in the immediate designated Mill Hill area (one of only 3 occupied homes of the 12). This renter stated that she attempted to purchase the house from her landlord but was unsuccessful only to learn that it had been sold to someone else. When inquired about who her new landlord was, she was told that the current landlord (UDA) had requested that their name or identity not be revealed to her. This is in direct opposition to the MAA’s report that they are ONLY purchasing abandoned homes. This was quickly brushed under the rug by the community meeting mediator (a lawyer provided from MAA’s legal firm)

MM: What steps did you take to address your concerns with the Macon Arts Alliance? What was their response?

SH: During our first meeting with Jonathan Harwell-Dye, both Ed and I shared with him that we were concerned about listening to mixed opinions about the Mill Hill project. We shared with him that there is a national dialog pertaining to utilizing art projects as a smokescreen for gentrification projects. Dye never gave us a response to our concerns.

Therefore, I requested for Harwell-Dye to connect me to the members of the African American community so I could learn more about the history of East Macon from their perspective.

EW: We shared with Harwell-Dye how important ethics are in our respective practices and we were keeping a keen eye on displacement and disenfranchisement. The MAA was not open to any critical discussions of the Mill Hill project. Samantha and I only had two meetings with the MAA before being terminated.

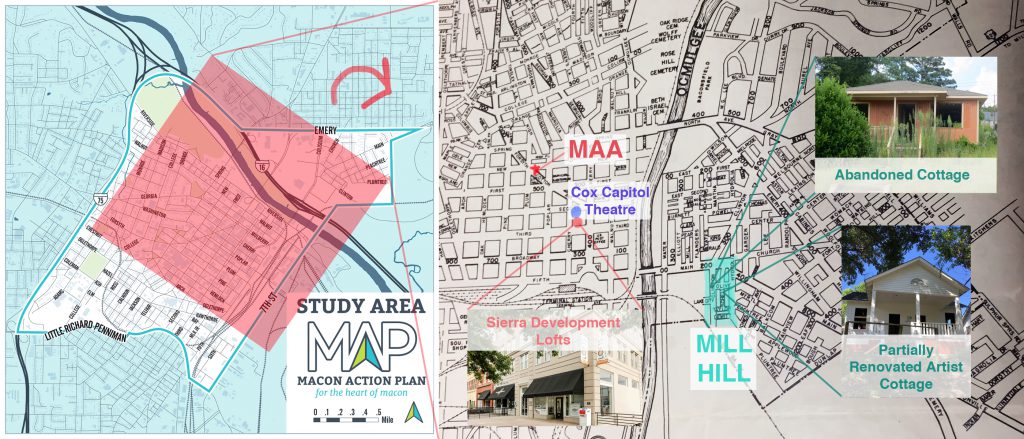

Composite image by Maya Mackrandilal.

This composite image offers some context to the area in question. On the left, I have appropriated a map produced by the Urban Development Authority of their “Macon Action Plan”– which plainly shows the area slated for development spilling over the river into East Macon. The red square superimposed on this map shows the rough area of the map on the right, an image taken by Ed Woodham at a local archive. It shows the neighborhoods before a series of developments over the past few decades that have added a sports Coliseum and Convention Center located near the Mill Hill site. The map on the right includes an example of one of the lofts that have been renovated in the downtown area (the number of lofts have doubled since 2012 according to a recent Macon Telegraph article). Sierra Development appears to be involved in quite a few projects in Macon, as well as across the country. The map also includes the location of the Cox Capitol Theatre, a building that was restored by Dunwody/Beeland (Jan Beeland’s husband’s architecture firm), along with images of an incomplete artist cottage and an abandoned cottage on the Mill Hill site (photographs taken by Ed Woodham).

Post-script: After this interview was conducted, Samantha and Ed connected me with two local activists who have been engaging with the communities around the Mill Hill project (Fort Hill and Fort Hawkins) to demand that their voices be heard regarding the relationship between the project and the neighborhood. They are community organizer Danny D. Glover and artist Charvis Z. Harrell, and you can hear their perspective through this Facebook video and this open letter to the Macon Arts Alliance.

Featured Image: Portrait of Samantha Hill and Ed Woodham, courtesy of the artists.

Maya Mackrandilal is an LA based transdisciplinary artist and writer. She holds an MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a BA from the University of Virginia. She has shown her artwork nationally. In her writing, which has appeared in publications such as The New Inquiry, Drunken Boat, contemptorary, Skin Deep, and MICE Magazine, she focuses on issues of race, gender, and labor. You can find her tweeting about politics and art @femme_couteau and can follow her on Facebook. Her website is mayamackrandilal.com.

Maya Mackrandilal is an LA based transdisciplinary artist and writer. She holds an MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a BA from the University of Virginia. She has shown her artwork nationally. In her writing, which has appeared in publications such as The New Inquiry, Drunken Boat, contemptorary, Skin Deep, and MICE Magazine, she focuses on issues of race, gender, and labor. You can find her tweeting about politics and art @femme_couteau and can follow her on Facebook. Her website is mayamackrandilal.com.