In a 2017 interview for the Brooklyn Rail, poet, critic, and theorist, Fred Moten said:

“Everything always needs new language. We constantly have to renew the language of any mode of inquiry. Some of the tools for that are in art history and some are in other places. If you’ve really got to do something, and it’s really important, you don’t give a shit where the tools come from. You get the tools wherever you can find them and then you deal with the consequences that attend those tools as you work with them. You don’t reject tools out of hand just because they come from this or that place. To me, that means you aren’t serious about getting the job done—you’re serious about something else, maybe about some bullshit notion of purity, but you’re not serious about getting the job done.”

This statement reverberates through table, a temporary project space organized by Kyle Bellucci Johanson, who has turned to building coalition through initiating critical discussions of contemporary art in the dining room of his Avondale apartment. Bellucci Johanson is an artist and teacher with an approach to art-making that is self-described as “transdisciplinary” and one that seeks to reassess value systems by working collaboratively in the hope of accumulating new tools to speak with and suggesting new political imaginaries through serious action. Bellucci Johanson is genuine in his discursive wonderment. His work is propelled by the overarching question, “What is contemporary art and what can it do to address the social concerns and issues we are facing today?” This summer I had the pleasure to sit at the table, per Kyle’s invitation, for the thoughtful dinner and discussion held in conjunction with “Salt in the I”, the last exhibition of the season featuring new work by Los Angeles-based artist, Andre Keichian.

Using salt, water, and wood as elements of discovery, Andre Keichian shares a sublime and solitary chronicle using original photography by their Armenian/Argentine grandfather in an attempt to draw connections between the personal history of the artist and their grandfather. Their “site-considered” installation is most evident in the large black and white photographs, framed in oak, curved and formed to the corners of walls and to the floor. The large photographs reveal a painterly quality, leaving the image to unfold several times before the viewer. Spurred by the dinner and discussion had while amongst Andre’s work, I invited Kyle for coffee to hear more about his project space, table, and its conception.

This interview has been edited with the consideration of a leading model for table: Ralph Lemon’s chapbook, On Value. How might we share private conversations– about art, politics, power, and community without compromising their intimacy, and in this case, the length in which a conversation may go.

Tamara Becerra Valdez: Can we start with your early experiences with cooking and sharing food?

Kyle Bellucci Johanson: I have been curious about food for as long as I can remember, and in my family it has been a way we care for one another. I am the oldest of three kids, and when I was in middle school my dad traveled and my mom often worked in the evenings so I watched my younger siblings and made dinner. I learned foundations from my mother and grandmother and quickly became obsessed and sought after any new food knowledge I could find. In college I had a number of friends who asked me to teach them how to cook, and I hosted Sunday dinners as a way to share time as a community.

TBV: What brought you back to Chicago?

KBJ: Inadvertently, actually, this time around. I grew up between Minneapolis and Chicago. My mother’s family is from Chicago and I’ve always felt more culturally grounded in here. I’ve also spent plenty of time in Minneapolis, which has been a home of sorts. I attended graduate school at CalArts from 2014-2016. After graduation, I was looking for work and hoping to stay in Los Angeles. I worked for a summer in Minneapolis at the artist-run space called The Bindery Projects, which was run by Caroline Kent and Nate Young, who are artists now living in Chicago. I curated a group exhibition called “anticamera” in October of 2016 and worked for Nate Young and Caroline Kent at the space. All the while I was applying for gigs thinking I’d be returning to Los Angeles. But the first job I received was at the Art Institute of Chicago. I had a lot of feelings about moving back to the city.

TBV: How many years had passed since you lived in Chicago?

KBJ: Eleven. It had been a good chunk of time since I had last been in the city. And Chicago has changed a lot.

TBV: How so?

KBJ: Gentrification is the catch-all term and perhaps the most reductive way to explain how the city has changed. The cost of living has risen. Chicago had a vibrant, local art scene when I left. It had its own school of thought. Its own ethos. Its own regionality. I feel like that specificity is more marginal now, more than it used to be. I don’t know. Times are tough. It’s even more expensive to be poor now than it was before.

TBV: What does economic justice look like to you? Maybe that is a big question to jump into early on but how does this history impact your new project space, table.

KBJ: No, it’s a great question and a good thread to go into for our conversation. In the project space statement for table, I believe the end line reads: “…we situate practices and facilitate critical discourse, building community outside of either institution or market.” That statement is completely intentional. My work is almost exclusively about expanding political imaginaries for ‘revolutionary becoming.’ It is often collaborative. So I was trying to find those kinds of conversations and spaces. I decided to make a space for those kinds of conversations to take place.

I wanted to do something that was extremely focused. All the artists I know who don’t have some kind of “in” such as generational wealth, legacy, family, or some kind of state-funded sponsorship, or really outside funding other than their own sort of resourcefulness and what they could do on their own, are really struggling. They are really great artists. Artists whose work is highly political, nuanced, and engaged in a discourse that I really believe in. I’m constantly searching for the next destabilization that makes me question what I think I understand about the world. I am interested in building culture and participating in politics, the way we see and frame and view and govern the world – its really difficult to situate your work when you are not in school any longer.

TBV: What did you study specifically in grad school at CalArts?

KBJ: I attended graduate school at Cal Arts from 2014–2016. I have an MFA from the School of Art with a concentration in Integrated Media. I was interested in the school’s radical legacy and transdisciplinary pedagogy rooted in conceptual and political traditions. I don’t think of making work through any commitment to discipline or medium so it was important to choose a school that would help me learn ways of thinking and speaking and situating my work. I am interested in participation in the systems of knowledge production, and I had witnessed CalArts help others to do that.

I’m not necessarily against commercial galleries or institutions, but I wanted to do something that operated in a different context to open space for practices and politics that may not be possible with the limitations either of those frameworks impose on artists. This also produces new limitations though, primarily funding limitations which I accepted going into it.

Economic justice is an interesting way to frame it. I don’t know if table is actively seeking or producing economic justice in concrete terms. It is a project built out of collective generosity and that is important. table is an experiment in collective generosity, when we make and value culture together, and if the generosity ceases to exist, then so goes the experiment.

TBV: Where were you, in your thoughts, your motivations when you created table? What was happening in your life?

KBJ: I can tell you the exact moment, actually.

TBV: Yeah? Okay. [laughter]

KBJ: I had been working at the Art Institute for two years in the Education Department. I appreciated a lot of the hands-on work I was able to do. I had been working with public school teachers building curriculum that was centered on critical thinking and meta-cognition. We were using art as a way to build critical thinking skills and critical discourse. It was a luxury to get to use art in a way that I believe art should be used, as something that instigates social participation and analysis, opposed to something decorative or rooted in the politics of negation or aesthetics, value-based structures or some kind of shallow version of cultural competency that celebrates the optics of diversity. As something that is only lip service, one that is definitely not interested in economic justice or racial justice. A lot of art education is framed in these contexts.

Despite enjoying the day-to-day work with collaborators and teachers across the city, for a variety of reasons, I realized that I did not want to continue working in that institution, in particular. Especially, in the context that I was working in, in terms of my academic freedom, intellectual curiosity, and personal politics. It became clear that I wouldn’t be able to do the kind of work I believe in at the museum.

Around the same time I started working at the Art Institute, I wandered into a lecture that was put on by two physicists who taught at SAIC, one of whom still does, Kathryn Schaffer. She is an astro-physicist who attended the University of Chicago and later taught classes there. Now she is faculty in the Liberal Arts Department at SAIC. Gabriela Barreto Lemos, a quantum physicist from Brazil, also participated in the lecture. The goal of the lecture was not to necessarily to talk about how art and science are related but, more specifically, how physics related to contemporary art discourse and how it might be useful for artist practices. In my work, I’ve looked to Karen Barad, a quantum physicist turned queer/feminist theorist. She has influenced my work on ghosts and thinking about things that are not necessarily not there. Those that are invisible, or absent. She wrote a book called Meeting the Universe Halfway. I wandered into that lecture loving Karen Barad’s work for sometime without knowing a lot of other artists who want to geek out over quantum mechanics in an in depth way. There are a lot of people who only want to talk about pseudo-science. I’m more interested in the science done in a lab. There is a gorgeous language in physics that builds mythologies around this kind of work. So, I went to the talk and later went up to Kathryn and Gabbi at the end of their lecture and asked them if they’d read Barad’s work. It was so cool! We instantly connected and became new friends.

TBV: Oh! How nice, like finding some kind of new kin!

KBJ: Yeah! Oh, kinship is an interesting word. We should talk more about that, too, because I don’t know if I have that. I feel kindred with a lot of people, but I don’t feel like I fit neatly into any communities. This is another reason why I started table. If anything, more than economic justice, the politics of table is about building coalition around a very specific way of having critical discourse. That, I definitely can say overtly, I am interested in cultivating.

Kathryn and I ended up developing a symposium all about the intersection of post-colonial theory, queer and feminist theory, quantum mechanics, and art, of course. Ultimately, the symposium was made up of Kathryn and I as moderators, students at SAIC, Charles Gaines, and Gabriela Barreto Lemos. A lot of artists use quantum mechanics as a metaphor for other things in the world but if we really take it seriously, we could argue that quantum mechanics undermines most of our practices as artists. Quantum mechanics obliterates language, for instance, and meaning.

TBV: What did you learn from the experience of developing the symposium?

KBJ: It was great to have someone trust me and build something like that and to advocate for me in an institution like SAIC and do this big project. This ultimately facilitated my transition from working at the museum to teaching at SAIC. So, yeah, table happened!

TBV: Yes! Let’s get back to that! table happened the night before?

KBJ: Yes, the night before the symposium I hosted a dinner with all of the people involved in the project. It was amazing! I wanted everybody to meet each other so that they felt more connected and familiar, and have some camaraderie. What is funny is – I think it’s ok to publish this [laughter] – the dinner was better than the symposium!

TBV: [Laughter] Okay, then, how so?

KBJ: There was no audience, no performance, or rather we were all the audience and all the performers. We were eating and drinking, and talking about the same stuff for the next day but in a much more informal setting that allowed people to be loose, be argumentative, and be more excitable about what they were passionate about. They weren’t being documented, photographed, or recorded. I woke up the next morning after the dinner and told my friends who were staying with me for the symposium, “This is it! This is what I want to do!”

TBV: You want to host the best, most discursive meal, yet! Would you add curator to your list of titles?

KBJ: No, no, no, no! I’m an artist who has an expanded practice and that is primary. I think artists are brilliant people who are constantly thinking about meaning and the politics of visuality and daily social life. We are good at it and we should situate our own work. I’m not saying that curators are not necessary, but I am saying that artists need to have a much more active role in how they are understood by people. One of the artists I admire most is Michael Asher who taught at CalArts. He never allowed anything into the world that he did not approve of. He is famously idiosyncratic and controlling of how his work moved through the world. I respect that so much, especially in the times we live in.

We [artists] often have a sense of scarcity. We need to hustle. We need to get ourselves out there. We are socially conditioned to say yes to everything. Even if it is not in our best interest, or subject to other power structures that may confuse people about our work – and also water down our politics – and ultimately what our work can do.

TBV: I think you are touching on how artists could harness more power collectively in situations where we are vulnerable to losing elements of our personal politics or what our work stands for. This makes me think about the discussion that was circulated after Michael Rakowitz declined the invitation to participate in this year’s Whitney Biennial. In an act of protest against the Museum’s vice chairman, Warren Kanders, he made the decision to stand in solidarity with staff at the Whitney and by his own convictions. Should we go there? [laughter]

KBJ: Let’s go there!

TBV: I remember reading about Rakowitz and feeling very invigorated by his decision. I asked several colleagues about it and what their thoughts were about his decision. I was disappointed when some felt like he made the decision based on his privilege. I was surprised by the overall reaction. How do we recover power in our collective decision making, as artists, when faced with issues that may compromise our values or ethics?

KBJ: This was a huge example. It’s interesting because we tend to produce these ideological binaries that I don’t think are actually accurate. In this situation, you should say yes. And then there is a counter argument, that I believe is a logical fallacy, that the only people who can afford to say no to this are people who have privilege. I would challenge any critic to take a look at the folks that we know as luminaries for social justice work around the world and ask themselves if any of those people had decided not to do what their convictions led them to do, especially because they were not privileged enough to do so, where the world would be?

I’m really sick of that argument. It’s a convenient way out to just be another aqueous neo-liberal. I think what he did was a sacrifice and what he did was a good thing. Yeah, sure, he has a successful career and I believe he would have done it even if his career was in a different stage.

I’m not interested in criticizing people who are standing up for justice. I’m not interested in purity – it’s not real. Comparative Olympics are a waste of time. How did we get here? [laughter]

TBV: Well, [laughter] you began talking about scarcity, the artist hustle, watered down politics. Just to circle back, you’ve shared a few situations that have influenced you in the creation of your artist-run project space, table. How do you select the artists exhibiting at table?

KBJ: There is no underlying formal or political consistency between artist practices. The work has been really varied. From poetic abstraction to representation-based practices, almost modernist dialectic structures, metaphoric considerations, and [work] like Andre Keichian, who is mining an archive and thinking abstractly and poetically through that archive. I’m interested in artists who are thoughtful and who have practices that are rooted in critical discourse or could highly benefit from critical discourse. This process is subjective. I’ll usually look for work that destabilizes me, my positionality, my understanding, and that takes time for me to sit with and, to be frank, that is serious. Made by people who, for whatever reason, believe in the power of contemporary art.

TBV: Especially for what it can do!

KBJ: It is specific. There are many reasons today to be an artist. There are many different ways to be “successful” as an artist that don’t contribute to cultural or knowledge production. There is no pressure to be capital “A” art. There is no need for perfection. Someone can share works that are a complete 180° for their practice that they’ve wanted to do for a while but have never felt they can do it in a public setting because of the institutional pressure to perform yourself in the way that people know you.

There are no neutral spaces. The project space at table is very particular. It is a dining room in an apartment building built in 1920 with old growth oak, woodwork everywhere, and only one wall that is not obstructed by a window or a door opening. And at the center of the room is a dining room table, designed and built by Nate Young and me.

TBV: Was the dining table constructed specifically for the space?

KBJ: Yes. He and I talked a lot about the table design and construction.There were a few things that I knew going in that I wanted to do. I wanted it made out of plywood. I wanted it to be an exquisite piece of furniture to be made out of the cheapest lumber material. It’s pine plywood. It has knots. It has warps. We had to laminate it, double it up and glue and screw the table into the floor. [Laughter] We did not have anything large enough to hold it down and make sure it was flat.

TBV: Exceptional skills! When I attended table for dinner at Andre Keichian’s show, I definitely noticed how I had to negotiate space when viewing the work around the dining table and in relation to the guests while I was sitting on the bench. I was mindful to not place my back to my neighbors while they were sharing stories at the dining table.

KBJ: When you’re sitting at a bench, you can feel the shifts and the people’s bodies moving next to you. You have an object that is mediating your connection as opposed to being in a discrete chair. It’s subtle, but it’s important. You have a physical connection to the people around you. You have to tell the person sitting next to you if you want to move or leave the table. Those little things matter.

TBV: Everyone had a complex personhood at the dinner. We shared so many intimate, personal stories for almost four hours that evening. How do you determine the guest list at table?

KBJ: [In the case of] the group of people who are invited to come in a show like Andre’s where the artist is coming from another city and doesn’t know the community of Chicago very well, I have more of a role in orchestrating who comes to dinner. Otherwise, I compile a large list of people that I think any one of them would be an interesting person to have at dinner for a variety of reasons, whether it is some kind of overlapping research, or someone with an oppositional viewpoint of the work, or who could be useful to make a more interesting conversation, or pose challenges to the ideas in the work. [I’m interested in] how the opposition can still create cohesion in the conversations. It still creates fullness.

There is a shared commitment to the understanding of building knowledge that I am wanting to make sense of. A disagreement is a buy-in and I respect this enough that I want to engage with you and argue with you. It points back to table’s mission of collective generosity. I appreciate when one can argue in a way that is constructive and propel everyone into a new territory of thinking and being together.

The dinner you attended was really personal. It’s the artists, the work, and the entire dynamic of guests at the dinner table that really make the evening. The artist is the host. We are all there at a dinner for them. You witnessed it.

TBV: Out of all the shows exhibited at table, how many artists have shown more personal subject matter in their work?

KBJ: Three out of four. So, I’ve never really understood, in my opinion, the arbitrary position of claiming that if a work is personal it is somehow not accessible to a wider or “universal” audience. That’s bullshit. The work I care most deeply about is so intensely personal and connects me to humanity or personhood. There is something much more at stake. I can’t help but to slow down and pay attention. You don’t want to miss work like that.

I don’t think that all the works at table are site-specific. Recently, a term that Andre used for their current show at table was that they make work that is “site-considered.” They do not make work that is negligent or disregards where it is located.

TBV: At dinner, you mentioned the structure of a critique class at CalArts that inspired you to create table. Are there other models of reference that have influenced you?

KBJ: There really isn’t a model that is being lifted or grafted onto this project, but there are models that I really admire because they did something to me. table is comprised basically of three things: the public exhibition, the dinner/conversation, and the publication. They are all working in service of the same goal which is to situate artist’s practices on their own terms. That’s the bread and butter of the whole thing. I was really interested in a publication as a structure or format that shared collective authorship as opposed to a singular voice of a curator, art historian, or a critic because those are the three we read most often on an artist’s work. Not every artist wants to write about their work, but at table an artist can select a group of people who they would like to talk about their work. They have a hand in structuring the conversations: like an orchestra, an artist tunes the conversation into something more reflective of what they are actually trying to do.

Ralph Lemon’s book, On Value, has one chapter of a conversation between him, Fred Moten, and Kevin Beasly. It was not a spectacle, by any means. It was a subtle, quiet gesture. It captivated me because it somehow maintained the electricity of being at a conversation and witnessing something that is unfolding before your eyes. This is what is so exciting about participating in dialogue because no one knows that is going to happen next. You are there and in it. Your consciousness unfolds. But what it also did is it somehow made that article more interesting because the documentation of that dialogue was sent back to everyone who participated. They had opportunities to edit, change their minds, add footnotes and add more clarity to what was being read in the final published piece. This tiny postcard-sized book had a big impact on me.

The other model was RE-CON, a critique class taught by Charles Gaines at CalArts. At the beginning of the semester, everyone is divided into partner teams. You and your partner have your critique on the same day. You take detailed notes about what happened during your partner’s critique. Then, you write a summary of the critique and follow with a written response to the summary. The two of you have one or multiple meetings with the faculty after the critique has happened and go through line by line of what happened in the critique and revisit everything. It was the most useful critique I have ever had. You know, often you walk into a critique with very little sleep because you have just completed the work – almost no distance between you and the work because it’s so fresh. You don’t even really know how to articulate. You can’t step back because you’re in it. There is no separation. Also, there is the social dynamic, anxiety, competition…all these other things at work.

TBV: Yes, including the politics of the critique and performativity that occurs.

KBJ: Yeah, the politics of the classroom, the performativity of the student or someone who wants to enact revenge or destabilize their practice from a previous conversation. All that shit happens. It’s weird because we all pretend that it doesn’t occur. [laughter] I think that if table can produce a document that exists in the world long after the show has come and gone, as a way of understanding that moment or historicizing that moment, and of being able to build a research body of an artist’s practice, then it is useful. I knew I really wanted to host a dinner, a multi-sensory activity that activated the mind and body.

TBV: It slows things down. It’s hyper-sensorial experience.

KBJ: It informalizes the academic framework in a way that I believe really matters. The structure of table is not really a critique. It’s not really a lecture. It’s critical but not interested in an evaluative structure like a critique. table is engaging with the work in the world and seeing what it’s doing.

TBV: table is a juncture for interpretation, critical discussion, a sensorial experience – with food and art. It activates a more lively discussion around the artwork. Let’s be clear: this is not relational aesthetics! The dinner and discussion is the not the artwork.

KBJ: Yeah! Bourriaud can go to hell! [laughter]

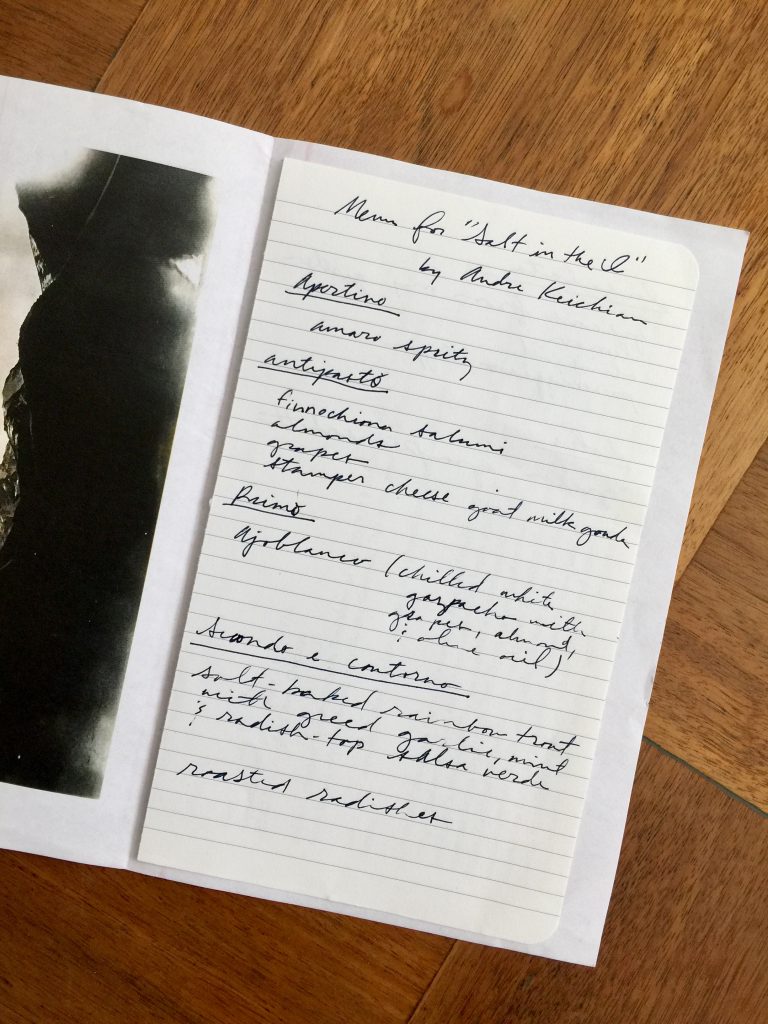

TBV: The menu for dinner during Andre’s show was impressive. Grapes were on the menu that evening, and salt, of course! I loved the white grape gazpacho! And I don’t believe I have ever had grape ice cream. It was a delicious meal. How do you prepare the menu for each exhibition?

KBJ: The first approach is the dietary constraints of invited guests. I strive to make the entire dinner edible for everyone. For three of the shows, the artists have had their heart set on a specific dish or type of food. Early on, it was very clear to me that Andre wanted me to use the salt that was produced through the making of their work to season all of the food. Sometimes the food is conceptual or very related to the work or celebrating seasonally delicious food.

The work itself matters too. I want the food to match the intensity/sensitivity of what we are viewing and talking about. Andre’s exhibition is very sensitive and precise. I wanted to serve food that was light and delicate, not distracting with aggressive seasoning, so rather than a rich pasta course, I chose to serve a chilled soup called ajo blanco made with green grapes, almonds, and olive oil.

TBV: Growing up with a family of tamaleras, bakers, and cooks, my upbringing was deeply connected to working, specifically towards teamwork, diligence, and how to have the big picture in mind. Often, I joke that I am at my best when I am put to a task and working. [laughing] I enjoy it! I like to problem solve. While in grad school, these qualities became more apparent. Eventually, in my art practice, I know I want a team to work with on future projects. I am seeing the fulfillment of this insight from my upbringing into my adulthood and career. What is a moment in your childhood that has deeply contributed to the artist you are today?

KBJ: This resonates with me. I don’t know if I can pinpoint a specific moment, but I can recall a couple of formative experiences. When I was in third grade I had a teacher who hated me – I wish I were speaking hyperbolically but I’m not. We had a capitalist propaganda/American exceptionalism curriculum masquerading as a unit to learn about the People’s Republic of China, and the teacher, Ms. DeVaulk, had us do a trivia game as part of the unit. If you repeated an anecdote about China that someone else had already shared you had to sit down. My friend Chris was called and proudly proclaimed his word “red panda” (a cute little furry creature that looks a little like a red raccoon). The teacher told Chris to sit down because someone had already said “panda.” I was outraged, fed up from months of biased power-wielding and third grade injustices. I stood on my desk, pointed at Ms. DeVaulk and yelled, “You’re a liar! There are two species of Panda in China!” I was promptly sent to sit in the hall and think about my actions, with hot tears streaming down my face. This moment, albeit hilarious in its childhood drama, was significant. I was outraged by her unfairness, and a “game” with rules that were not followed by the referee. I didn’t know what hegemony meant in third grade, but much of my adult life has been spent studying the politics of communication, image-making, and the rhetoric of truth. I want to participate in making spaces that protect people from exploitation and work that illuminates futures rooted in a concern for justice.

The second memory is from high school. I was the “editor” for an underground zine, a counterpoint to the “state-sponsored” school newspaper. The writers all went by pen names to protect their identity, and I collected all the work individually to further safeguard this. Someone wrote a sardonic criticism of the school mascot, Pirate Pete, in which, among a litany of other concerns about the moral implications of using a pirate as a cultural symbol for the student body, they skillfully and subtly compared his musket to a sex toy. The administration somehow missed the subtlety, interpreted the essay as a potential gun threat, and subsequently interrogated any student who knew anything about the zine. I was found out and called to the office under threat of suspension if I didn’t reveal who the author was, and in my moment of need, my art teacher, Susan Chun, (who also secretly copied our zine for us) burst into the principal’s office with the student handbook on the bill of rights, citing each way in which the authors and I were operating within our rights as citizens and how we were being unlawfully interrogated and threatened. I had previously only had family members defend me like that and I knew in that moment I wanted to be an artist, and a teacher.

The third formative experience happened later, after I had finished undergraduate work, as a young artist working in Minneapolis. Caroline Kent and Nate Young built an artist-run space in called the Bindery Projects which became a kind of sacred space for young artists with politically motivated practices. They served as a refuge for many of us who were discouraged by a lack of diversity we saw in the kinds of practices being lauded by institutions and markets, and their space continues to serve as an inspiration for my own work as an organizer to this day.

TBV: The clarity you have of these past experiences are impressive. It crossed my mind to share a quote from a conversation with Mylène Ferrand Lointier and Hans Ulrich Obrist that I believe you would be interested in based on your attention to the potential of an artist’s work. Let me reference it…Did you know that UIC hosted Bruno Latour for a master class last year at the campus?

KBJ: WHAT!?

TBV: Yes! It was part of my graduate research position to assist in organizing his master class and the symposium that followed after his week long class.

KBJ: Oh my God, Tamara! I can’t believe I missed that! I love Bruno Latour.

TBV: In the interview, they discuss Obrist’s collaboration with Bruno Latour and how they began working together. She asks him, “What is your opinion about the situation and the political remobilization of art that we are witnessing today?” And, Obrist responds:

“We have to consider the practices of the extraordinary, extremely politicized – in both an artistic and activist sense…It is therefore not necessarily a matter of going beyond the questions of art, but about going beyond art…From now on, what is important is not so much the category as the practice, but more generalist practices. I also think that it is necessary to create a pool of all knowledge to be able to pose the big and urgent questions of the 21st century, regarding issues like ecology and inequality. As scientists, artists or architects alone, it is impossible to resolve these problems. This is the reason why more and more collectives are created…We no longer live in an era of isolated geniuses, but rather in an era of research networks.”

KBJ: Yes. Yes. Yes. And, I would even challenge it further – what is the impetus to even want a totalizing power to have a discussion about culture? It’s an amalgamation. This constant flowing, evolving, changing set of rites, rituals, practices, traditions, and beliefs enacted by people over and over, and over again. It’s crazy to think that anyone could have singular power to talk about something that is so unwieldy and constantly changing. Political work that is not engaged with the positionality of the artist, well, what world do they live in? It is a privilege to assume that an object can do all the meaning-making on its own regardless of where it is.

TBV: What have been some of the major challenges that you have faced in creating table?

KBJ: The only challenge, which isn’t very interesting, is the financial challenge. If you are not going to be a non-profit or a for-profit, then what are you? [laughter] To be honest, I hate soliciting. My cultural ideal is a community of gift-giving and reciprocity and exchange, and that people help each other out. Not to reconcile debts, but more so something like, “I have these skills, you have those skills, so let’s help each other out.” I’d prefer to work that way. It’s not that it’s not easy but it’s not socially acceptable.

TBV: To help sustain the project space for the next season, will you host a fundraiser for table?

KBJ: Yes, in July and August. Where I landed on this issue of raising money is that if it’s integrated into the ethos, the system, and production of table, I will do it. We are going to do four fundraisers this summer. I’m asking four people to host each fundraiser dinner at their home. I will provide all of the food. Guests will purchase a ticket for the meal. The host is committing to enthusiastically supporting the project and purchasing one of the prints. Aron Gent from Document extraordinarily, generously is printing an edition of each artist’s work for table – FOR FREE. It’s unreal. Guests will have an opportunity to purchase these prints, as well. This is how we will fund next year’s shows.

TBV: How much is a ticket for the fundraising dinner?

KBJ: A five course dinner with wine is $100. The print editions are $250. One dinner could pay for an entire artist’s show. Everything was out of pocket for our first season.

TBV: What can you share about the artists for the next season of exhibitions? Any Chicago artists in the mix?

KBJ: Absolutely! Confirmed artists for this upcoming season are Quito, Ecuador-based Paul Rosero Contreras, Philadelphia-based Lily Kind, Los Angeles-based Lucia Prancha, and Chicago-based artists, Nyeema Morgan, and Sanaz Sohrabi.

TBV: Let’s close with this question: what do you eat for dinner alone?

KBJ: I try not to eat alone – food is better for and with others – but if I must I usually eat a salad with citrus and shaved vegetables, and pasta, orecchiette with cime di rapa and anchovies is a favorite as well as bucatini all’amatriciana (a chile tomato sauce with guanciale and red onions.) Of course, wine is important and fernet afterwards helps both food and ideas to digest.

Featured Image: Andre Keichian, ‘Salt in the I’ (detail), 2019. View of negatives from Keichian’s family photo album adhered to a glass window, part of the exhibition installation at table. Photo by Kim Becker. Image courtesy of Kyle Bellucci Johanson.

Tamara Becerra Valdez is a visual artist based in Chicago, IL. Valdez earned her BFA at the University of Texas in Austin and MFA at the University of Illinois at Chicago (2019). She is currently a BOLT Resident Artist at the Chicago Artists Coalition for 2019–2020. Photo by Jae Kim.