Scrolling, swiping, and clicking are the only tactile skills required to engage with Institutional Garbage, a web-based exhibition produced by Sector 2337 and the Hyde Park Art Center. These actions, performed by a mouse, keyboard, or the tap of a finger, make a ritual out of interacting with exhibitions presented in the digital sphere.

Co-curated by Caroline Picard and Lara Schoorl, Institutional Garbage conceptually tears down the institutional walls of the art world, from elite academic spaces to donor-run museums, to showcase “the administrative residue of imaginary public institutions.” [1] As the title insinuates, the show makes a point to draw attention to the seemingly imperfect “trash” of 41 artists, writers, and curators.

Lara Schoorl, a recent graduate of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and current publicity manager at Sector 2337, states that the exhibition aims to “elevate the connotation of trash,” attempting to understand it as a crucial component of the creative journey through the art world. Schoorl described in detail how this innovative rendition of a virtual exhibition initially “started from a question posed by Caroline to imagine a utopic institution that did not exist.”

In grappling with this conundrum, Picard and Schoorl stretched the boundaries of the art world to re-conceptualize the potentiality of future of museum spaces. They use the virtual as their artistic medium, including email threads, unrealized exhibition proposals, rejection letters, and fictive admission letters, to curate exhibition content. Institutional Garbage thus puts the process of curation in reverse—it starts from the administrative ephemera of everyday correspondences, interactions, and very real human feelings of restlessness and failure, to place them at the forefront of exhibition-making. It makes a point to archive the forgotten remnants of back end activities of public institutions, demonstrating how these invisible liminal acts are crucial to allowing large-scale institutions to function for the public.

Together, Picard and Schoorl envision ways that mundane bureaucratic spaces can formulate an exhibition.

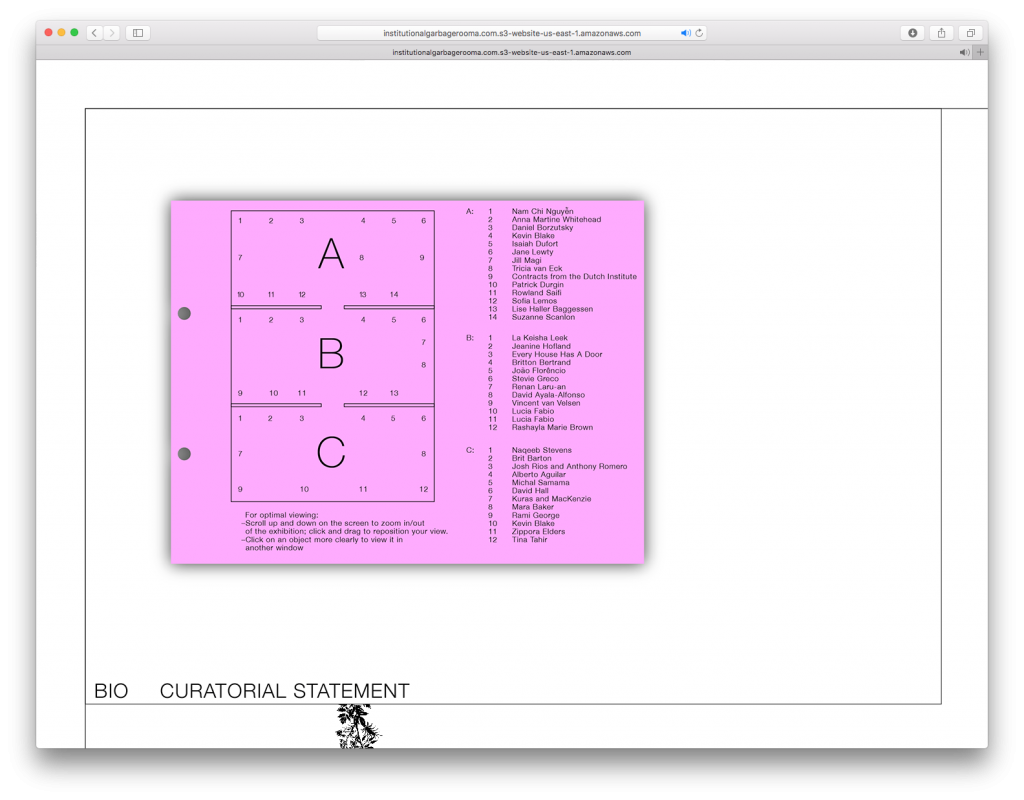

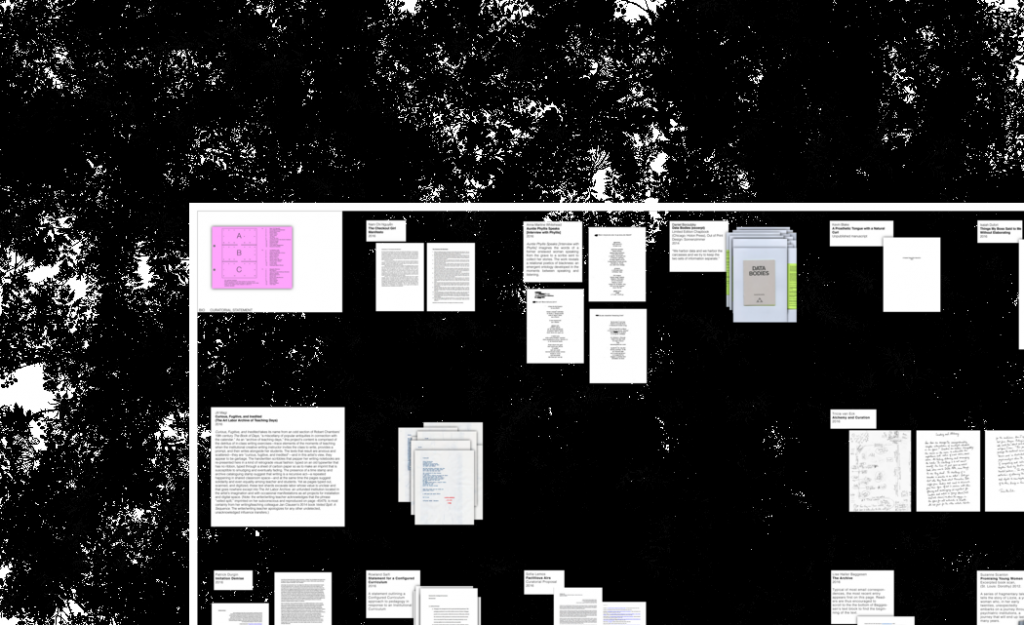

Institutional Garbage starts with a single image of a pink floor plan showcasing individual “rooms” of artists and their works—a signature of navigating traditional art spaces. Once the viewer zooms out of this singular image, the infamous white walls of the conventional art institution are represented as digitized white lines that precariously border a decentralized conglomeration of floating webpages. Designed by Pouya Ahmadi, the elements that comprise the show consist of three virtual rooms labeled as Room A, B, and C. They contain a diverse selection of mediums: snippets of untraditional poetry, discarded drafts, paperwork, and drafted notes.

Upon first click, each work initially appears to be scattered on the page. However, after navigating the rooms with a cursor, the viewer becomes acquainted with the non-hierarchal nature of the exhibition’s composition. The multiple methods needed to navigate the site, ranging from zooming in and out of large pages to sifting through individual tabs, make moving through the exhibit unintuitive.

But once the visitor begins to revel in the fact that an erroneous tap could lead to a close up of an individualized piece of work, the exhibition space acquires an aura of serendipity and innovation. The fluctuating design of the website, oscillating between different perspectives, literally strips the foundation away from this imaginary institution.

Visually grounding the exhibit behind the virtual rooms and works of art is an abstracted background image of leaves and an open sky. Its amorphous shape, juxtaposed against the rigid rectangles of the virtual walls of the exhibit, adds a sense of visual coherency that locates its viewer back into the natural world. The perspective of the background image positions the viewer to look upward towards the sky—perhaps a testament to the exhibit’s theme of approaching the art institution from the “ground up.”

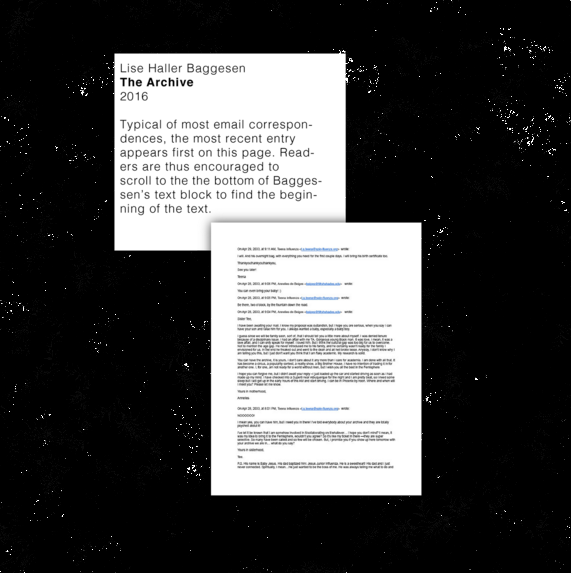

Lisa Haller Baggenson’s piece The Archive demonstrates this theme perfectly. The Archive is prefaced with the blurb “typical of most email correspondences, the most recent entry appears first on this page,” bringing attention to the design of email threads which are often read backwards in time. Despite this, the email is dated on the futuristic date of April 29, 2033, warping a sense of time altogether. To further dislocate the viewer, the thread starts mid conversation:

I will. And his overnight bag, with everything you need for a couple of days, I will bring his birth certificate too.

The context of this correspondence is generally undetectable, but as one reads more closely, the email plunges the viewer into a highly sensitive issue. The receiver, Annellies, has been denied tenure for sleeping with a TA. Described as a “disciplinary issue,” Annallies admits to being a “flaky” academic for her emotional love affair with a “gorgeous young black man,” but claims to still retain her “solid” research skills. Beggenson thus touches upon the disconnect that can exist between personal desires and the bureaucratic rules of institutional spaces, often unaddressed in the public sphere.

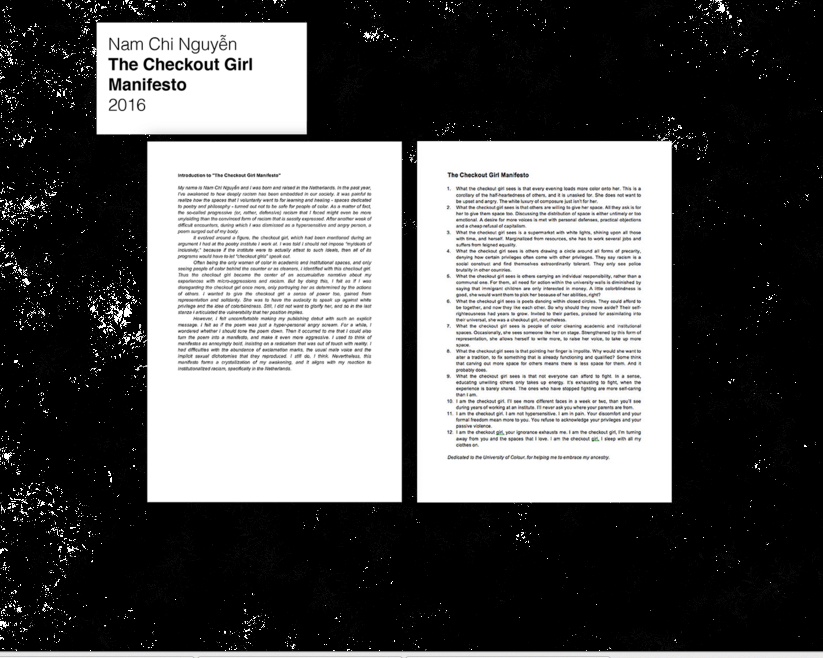

“The Checkout Girl Manifesto” by Nam Chi Nguyen vulnerably touches upon “how deeply racism has been embedded in our society.”[2] The introductory paragraph expresses how it was painful for the author “to realize how the spaces that [she] voluntarily went to for learning and healing—spaces dedicated to poetry and philosophy—turned out not to be safe for people of color.”[3] This racially conscious piece of nonfiction uses a protagonist of an unnamed “checkout girl” to be the “center of an accumulative narrative about [Nguyen’s] experiences with micro-aggressions and racism.” Using the repetitive declaration of “What the checkout girl sees…” each point of the manifesto reveals the hard truths of being a person of color on the margins of institutions that are often advertised as incubators of progressive thought yet, at times, perpetuate the very elitist thinking it condemns.

Works like Baggenson’s and Nguyen’s showcase how the uncomfortable “residue” of institutions is often silenced in traumatic ways and, as a result, internalized.

Institutional Garbage exists as an organizational critique of the often exclusionary practices of art institutions. What Institutional Garbage excels at, in the midst of primarily text-based works, is archiving the emotional baggage carried within, which can often be transferred to material objects in art spaces. Despite it’s virtual form of an online exhibit, it allows for the unwanted feelings of hesitancy and doubt to surface.

Artist and curator Rashayla Marie Brown’s work featured in Room B, a room showcasing the unrealized exhibitions proposals by curators in 140 characters or less. Brown shows how unpredictable administrative titles can appear to be, summarizing her exhibition proposal as:

The artist curates curators who used to be artists 2020 features explanation from those who gave up and became curators.

Brown’s trite phrases make a sarcastic, Basquiat-esque evaluation of the arbitrary nature of institutional roles. The assertion that artists “who gave up and became curators” further comments on the practicality of art-making, casting uncertainty around the field’s ability to generate revenue.

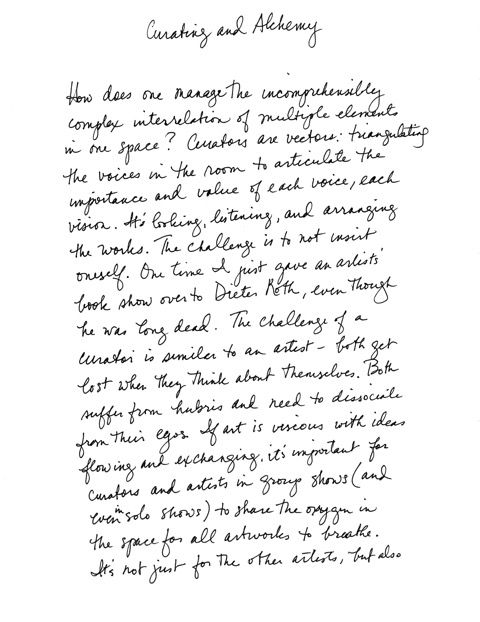

Although cloaked in sarcasm, a piece like Brown’s demonstrates how the expression of raw and vulnerable emotion is frequently looked down upon within institutional hierarchies, and as a result, remains masked. Many pieces throughout the exhibit, like Tricia Van Eck’s Alchemy and Curation, become streams of consciousness that have the ability to break through bureaucratic barriers.

Collectively, Institutional Garbage’s selections of work comment on the emotional strain of working in a capitalist society that measures productivity at the expense of the personal, such as feelings of love and exclusion. In doing so, it demonstrates how trials and tribulations are inherently embedded within institutional successes that can lead up to the large-scale programs like biennales, fundraisers, galas, and blockbuster exhibitions.

So, while this online exhibition is in the form of the imaginary, intangible, conceptual, and virtual, it generates questions concerning what lies beneath the intangible, such as “how does one digitize emotion?” or “how does one archive loss?” While it does not present many answers, it provides evidence that vulnerabilities and setbacks are a part of a collective experience.

This show will live in cyberspace until December 30th.

[1] Institutional Garbage, http://www.hydeparkart.org/exhibitions/institutional-garbage, 2016.

[2] Introduction to “The Checkout Girl Manifesto”, http://sector2337.com/sector-daily/page/8/#institutional-garbage-nam-chi-nguyen, 2016.

[3] Ibid.

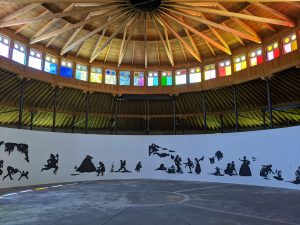

Featured Image: Detail of La Keisha Leek’s “Super Nova: Joan E. Higginbotham and Mae C. Jemison”

Sabrina Greig is an art critic in Chicago, originally hailing from New York City. She received her MA in Art History from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago with a focus on representations of the Black diaspora in pop culture, fine art, and gentrified urban spaces. Sabrina is a current curatorial fellow at ACRE projects located in Pilsen and has curated shows at the Haitian American Museum of Chicago as well as the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Her literary work has been published in Fnewsmagazine and Bad at Sports.

Sabrina Greig is an art critic in Chicago, originally hailing from New York City. She received her MA in Art History from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago with a focus on representations of the Black diaspora in pop culture, fine art, and gentrified urban spaces. Sabrina is a current curatorial fellow at ACRE projects located in Pilsen and has curated shows at the Haitian American Museum of Chicago as well as the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Her literary work has been published in Fnewsmagazine and Bad at Sports.