“Brilliant and divisive,” those were the words Catherine Edelman, gallery owner and panel moderator, used to describe acclaimed photographer Joel-Peter Witkin. The latest exhibition at Catherine Edelman Gallery, Joel-Peter Witkin: From the Studio, features more than 25 photographs, 80 drawings, as well as sketchbooks and journals, darkroom tools and cameras, letters, and contact sheets. But it was Witkins mission, “to create photographs that show the beauty of marginalized people,” and how he executes that aim was the primary topic of discussion for the ‘Otherness & Beauty’ panel hosted by the gallery on June 1. The panel included painter, writer and disability activist Riva Lehrer, art therapist Deb DelSignore, and art historian Mark B. Pohlad.

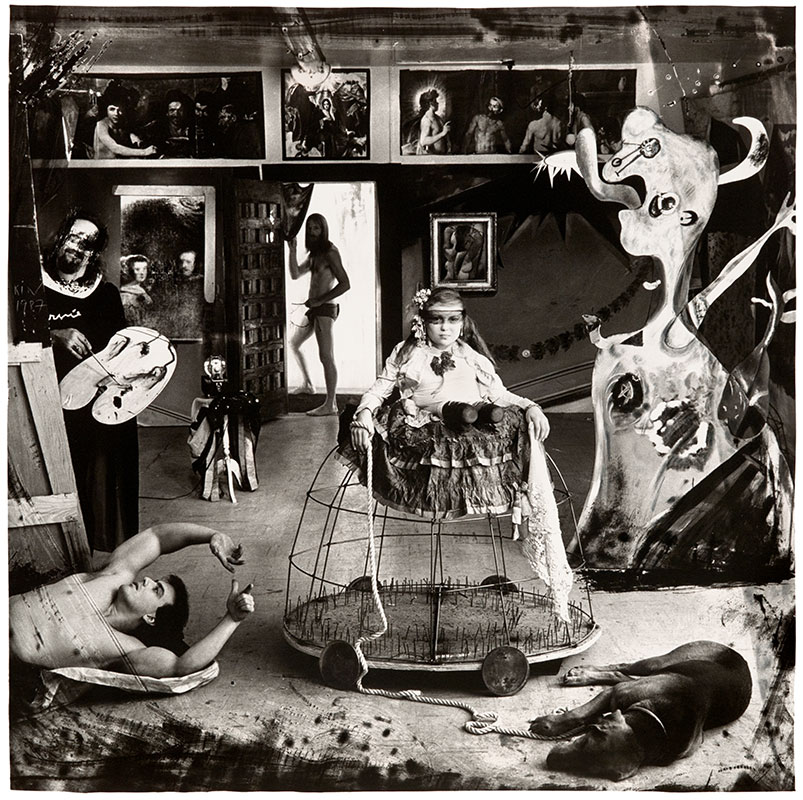

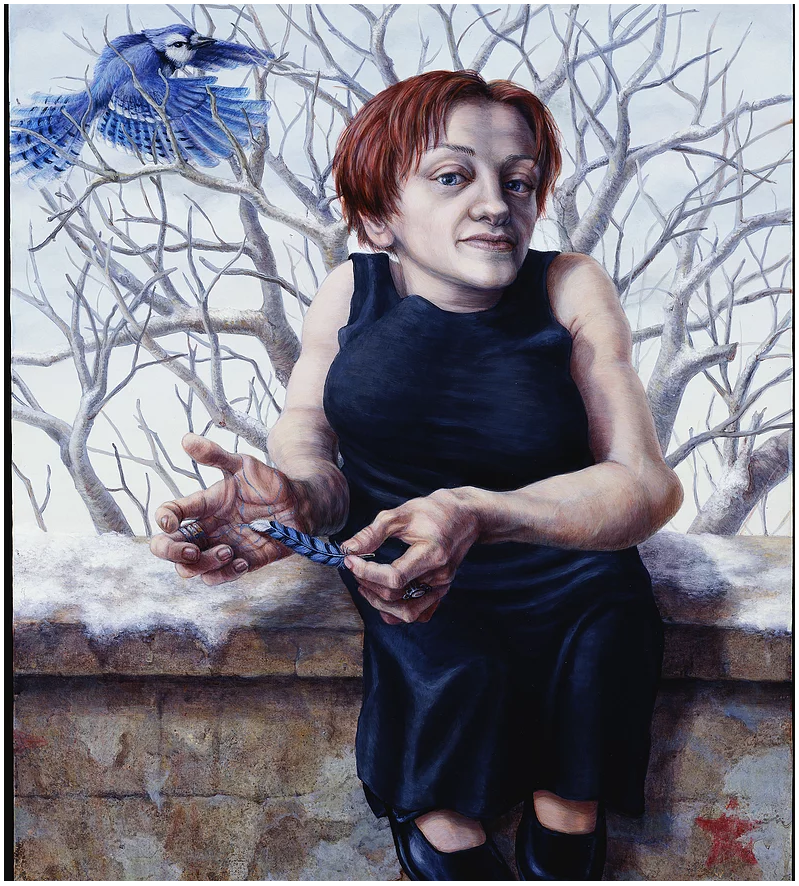

Witkin, an American artist based in Albuquerque, photographs his subjects in carefully crafted settings and utilizes manual darkroom techniques to produce surreal images. The subjects are often “intersex, post and pre-op individuals, and people born with physical abnormalities.” Lehrer makes artwork depicting similar marginalized people, with one very important difference—she is a portrait artist. Lehrer works collaboratively with her subjects to portray their individuality, regularly subverting stereotypes. Witkin’s work is decidedly figurative, rather than portraiture. In figurative work, subjects are “subservient to and at the mercy of the artist,” Lehrer explained; they disappear into the narrative, becoming actors rather than people. Through his work, Witkin is “constantly obliterating the body,” creating a “destruction of wholeness,” said Lehrer, that reinforces the portrayal of disabled bodies in the art historical canon. For centuries, people with disabilities were used to show the healing power of God, violently used as props to demonstrate religious lessons. Because Witkin references art history so directly (his The Raft of George W. Bush, NM is an obvious parody of Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa), this context cannot be ignored.

Witkin sees his work as “elevating marginalized people to the point of beauty,” said Edelman. This implies that marginalized people need the non-marginalized to take some kind of action in order to make them beautiful, which couldn’t be further from the truth. This difficult portrayal of ‘otherness’ is further complicated by Witkin’s recent diagnosis of dementia. Witkin has stated that A Mermaid’s Tale will be his last photograph, as his symptoms have “left him unable to create art.” Art therapist DelSignore noted that “he may begin to experience this otherness himself.” While some questioned why his work has to come to an end since people often continue creative expression through conditions like dementia, there was an emphasis on respecting people’s self-identified capacities and that those capacities are ever-changing.

Artist Michael Taylor Orr, who attended the panel with me, remarked at how A Mermaid’s Tale “still has a sense of melancholy, but with more warmth.” The piece has a noticeably softer tone, and having been made after Witkin’s diagnosis, it’s hard not to read into the shift towards a more tender and compassionate scene. The set for this work has been recreated in the gallery, a unique moment of color in the space. As for A Mermaid’s Tale being his last photograph, Orr said if Witkin “pursues his work, which I hope he does, I think it might be even more interesting coming from a more direct introspection of his newfound, but true self.”

Orr also talked about how “the relationship between an artist and their work is often so different from what is perceived.” In their work, Orr also depicts ‘othered’ and exaggerated bodies, but “as a way of self-healing.” Witkin has cited a couple traumatic childhood experiences as catalysts for his curiosity around people with disabilities as well as the dead. “Witkin was a witness to death, I’ve also been a witness,” says Orr, “I don’t know why that fascination becomes embedded.” Orr discussed how searching for ‘the why’ turned into an admiration for the beauty in the human body. This interest has since shifted towards the philosophical, with physical portrayals of mental pain as the subject in much of Orr’s art. “Disabilities and mental illness have a very negative discourse around them, but my generation also glamorizes it—they put it in their Instagram profiles,” said Orr, “it’s a fashion statement.”

It’s a broad and complicated spectrum from stigma to romanticism, but it’s through conversations like this panel discussion as well as deep looks into work like Witkin’s that understanding is built. “I think we should be talking about each other constantly,” said Lehrer. I was impressed Catherine Edelman Gallery hosted such a program to dive into the complexities of Witkin’s work through critical discussion—critical as in important as well as critiquing. However, I would be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge that the talk was held on the lower level of a space without an elevator or a ramp that meets ADA standards, which made it quite clear just how far we still have to go in terms of accessibility. While it is about small slights that add up to oppression, we are also in a political climate that is waging war on disabled bodies. As Lehrer says, “the stake are really high; this is about whether disabled bodies are valued.” Through Witkin’s work we see a troubling depiction of ‘elevated’ marginalized people, but we also find urgent conversations with others, and ourselves.

Joel-Peter Witkin: From the Studio is on view at Catherine Edelman Gallery’s new location in West Town through July 3, 2019. You can view more of Michael Taylor Orr’s work on Instagram and Riva Lehrer’s work on her website.

Featured Image: A black and white photograph with a multitude of surreal figures. At center, a woman with a partial leg sits atop a cage-like structure on wheels with a sleeping dog at the bottom right. On the left, a bare-chested man lies on the floor, modeling for a painter holding his palette. In the background, a man exits out an open door. Art historical and religious references fill the room. Las Meninas, New Mexico, 1987 © Joel-Peter Witkin / image courtesy Catherine Edelman Gallery, Chicago.

Courtney Graham is a Chicago-based arts administrator, writer, and event planner. Her writing and research focuses on accessibility for people with disabilities in cultural spaces, exploring access and spotlighting artists with disabilities. Courtney serves as the Assistant Director of the Evening Associates at the Art Institute of Chicago, engaging the museum’s next generation of art-minded philanthropists. She completed her BFA at the University of Michigan and her MA at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.