Of the countless exhibitions, essays, programs, and projects that are dotted throughout Chicago’s art history and the world because of Hamza Walker, there’s one that sits at the forefront of my mind. The show was Suicide Narcissus, an exhibition he organized at The Renaissance Society in 2013. I visited the exhibition multiple times for the sole purpose of seeing the piece Leviathan Edge (2009), a 30-foot long suspended skeleton of a sperm whale by Lucy Skaer, which was enclosed by a series of walls, making it mostly hidden in plain sight within the gallery space. Though it was largely closed off, there were small gaps in the walls, occasionally revealing series of vertebrae or the massive skull, bringing me closer to a whale than I had ever been. There was something I enjoyed about my access, visual and physical, being restricted, not getting the satisfaction of being able to see everything easily, and having to fill in the blanks of what I was seeing. Looking back, I realize that I was attracted to that piece because of my appreciation for mystery and the charge given by the artist to complete the fragments for myself if I chose to.

I bring this up because Leviathan Edge serves as a kind of metaphor for how Walker has operated during his thirty-two year chapter in Chicago–a steady voice with a hint of stealth, whose presence whispers at times and becomes emphatic and booming at others. Since the ’80s, he has worked behind the scenes and alongside many to support Gallery 37, Urban Gateways, Randolph Street Gallery, and the art collections at Chicago Public Libraries. He has taught classes, visited many artist studios, voiced his thoughts on panels, and sat in on endless crits, nurturing a generation of artists, writers, and curators. He has built his jazz chops with Southend Music Works and under the moniker Mandrake for WHPK, and given shape through words and exhibition-making to the Renaissance Society and the artists it shows from around the globe. He made the original 53rd Street Hyde Park Art Center into a semi-secret indoor haven for skaters before the skate parks well-known today started being built around the city. Then, marked with the scratches and tracks of Chicago skaters, it has been exported to Germany and San Francisco, with a final landing place in Los Angeles. The list is long and endless.

I say this all to say that we think we know the full mark that Walker has made over the last three decades, but the truth is we may never get a full view. Even as a transplant, it’s impossible to truly see roots that have reached the depths that his have. For now, we will hold and appreciate the slices, vertebrae, jawbones, and fragments that make up this chapter and lead into the work that he will go on to do in the next.

Nevertheless, I wanted to collect as many fragments as I could before he made his exit to Los Angeles as the new Director of LAXART. So, at a small coffee shop in Pilsen, Walker spun a web of memories, many sparked by gold-marked tangents, leading to the cast of characters, spaces, and experiences that he’s collected since landing in Chicago from the east coast in 1984.

Tempestt Hazel: How long have you been in Chicago?

Hamza Walker: I’ve been in Chicago for 32 years. It’s interesting to see how things change. [When I moved here] the needle just got dropped in the record and this is where I came in on the story. You don’t think that the parts you’re witnessing will in and of themselves become historical. But sure enough, they do. [laughs] It becomes very funny to think that way, but you only think that way in relationship to change.

TH: Have you recently had time to reflect on things from your past that you now recognize as having resulted in significant historical impact or influence?

HW: No, I’ve just been putting one foot in front of the other. There’s been nothing monumental, just a succession of things and exhibitions.

TH: But in 30 years you’ve been able to see how the city shifts over time…

HW: To see the late ’80s when I used to go to River North–and that was the new gallery district [at the time]. People would talk about how the gallery district used to be east of Michigan Avenue, near the [Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA)]. And now, people say “Oh, the old gallery district used to be in River North…” [laughs] That was interesting to see–to watch it happen in real-time. Now, there are still galleries in River North but it’s not the center. Now, it’s maybe the West Loop.

TH: What were some of the important galleries or who were some important people for you at that time?

HW: Donald Young and Rhona [Hoffman]. It was the Young Hoffman Gallery for a while, and by the time I came to Chicago they had split up.

It was interesting to also have spent [time with] and to have known Chicago grande dames like Ruth Horwich and Lindy Bergman. They’re two generations above me, but I like having an intergenerational cohort, as oxymoronic as that sounds. I felt as connected with them as I do to people who are younger than me now, now that I teach and have students. It’s very beautiful. What do we do with our experiences? Do we assume that the experiences we have are similar to others’ experiences–to think, “Oh, doesn’t everyone have that intergenerational cohort?” When I think about Lindy and Ruth, I remember their basic accessibility and how often they would open up their homes and have parties. It seems like everyone has access to that, though maybe it’s a different time and a different era. But that was very beautiful–the openness of the community here. I never in the slightest felt intimidated by an art world insofar as what I knew to be an art world was Chicago at that time. It always felt very open and accessible, even intergenerationally.

TH: I think that happens now, though I can only speak to my experience. There was a time when it was intimidating because I was learning the landscape. I became fans of people–and there’s an invisible, and temporary, divide that I created with that. But as I moved closer and closer to these people and interacted with them more, started to see them as friends and worked with them, things started to open up. But I would never find myself wandering into someone’s party or home in the way you’re talking about. That’s only happened to me a handful of times.

HW: Yea, so I worked at Urban Gateways with Ronne Hartfield, who knows everybody and all the Chicago grande dames. I would see Don Baum, who was close to Ruth. I can’t remember the first time I went to Ruth’s home–and it’s beautiful that I can’t remember–but it was probably for a luncheon. Something to do with Urban Gateways. It got to the point where it felt like Ruth’s home belonged to everybody. I knew Ruth through Don because she hung out with artists. But it never felt like another world.

TH: What were you doing at Urban Gateways?

HW: I was a secretary in the fundraising office.

TH: You weren’t necessarily part of the education work that they do, rather supporting it.

HW: Right. I knew the artists who were part of [Urban Gateways]. I’d go out to events, only on occasions to schools. I wouldn’t see them perform as artists inside of schools as much as I saw their lives as artists outside of that. They would have exhibitions and I would go to them. Or they would drop off exhibition announcements, or say that they were going to be in a performance at [Club] Lower Links.

TH: Let’s step back a bit. You landed in Chicago in the ’80s to go to school at the University of Chicago…

HW: 1984.

TH: So, after you graduated…

H: I never graduated, technically. That’s what’s really funny. I still owe the University of Chicago a dissertation.

TH: Really? And you’re going to give it to them?

HW: I have to give them something. I did all of my four years and all of my coursework, but I kept getting jobs.

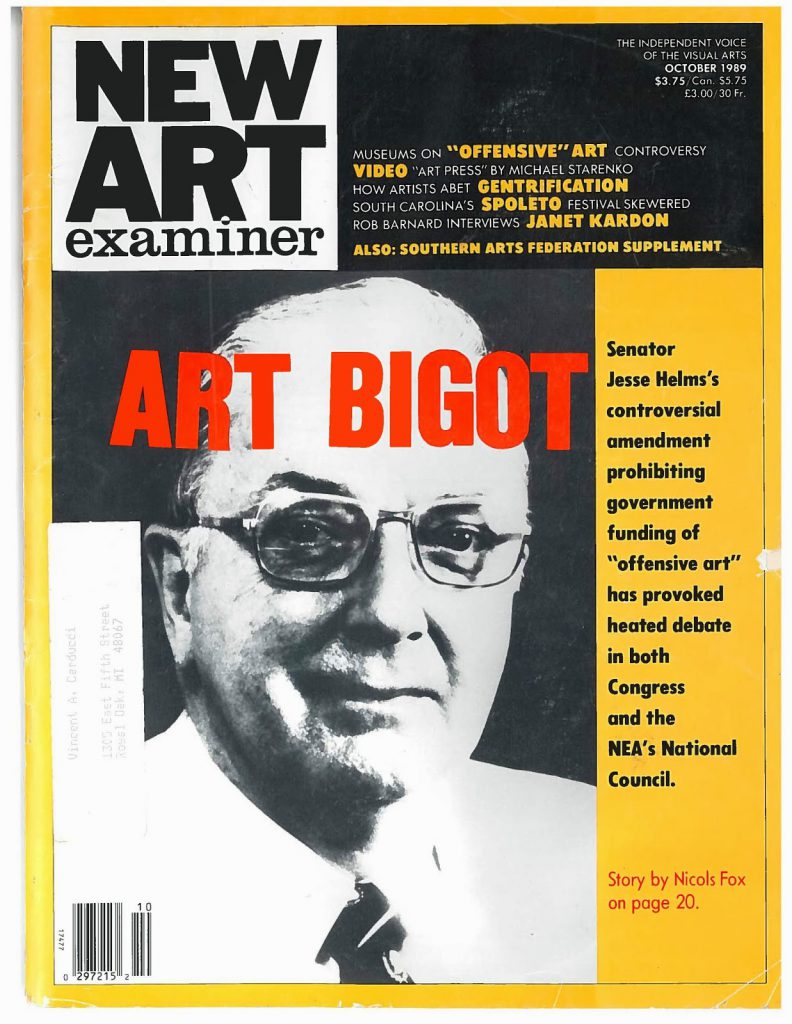

And I didn’t like writing–I still don’t like writing. But my boss at Urban Gateways taught at University of Chicago and he taught me how to write, [especially] basic office correspondence. I knew how to write a paper, but I never technically learned, so it remains extremely torturous. At that time I could articulate my thoughts, but I just couldn’t write them down. I worked with Mike Lash at the Public Art Program starting in 1990/91 to 1994. Mike introduced me to the Allison Gamble who was the editor of the New Art Examiner. Mike told her, “[Hamza’s] always talking shit. He has a lot to say. Why don’t you ask him to write reviews?” So, Allison, who was delightful, gave me some reviews to write. It was Allison, Kathryn Hixson, Deborah Wilk, and, later, Anne Wiens. [It was] writing for them and for the New Art Examiner, writing for a magazine, and having to make sense for an actual readership as opposed to writing for papers at school–that helped me organize my thinking on paper. And them making suggestions like, “You may want to think of it flowing like this…” They were important on that front.

TH: It sounds like it was important for you to have people around you who could identify and make that connection for you and provide an outlet that could challenge and push you to write your thoughts down…

HW: Right. That was key as a learning experience, but one that was, again, by way of a kind of accessibility. It was like, “Hey, kid. You. You have something to say? Write 500 words, right here, right now. Drop and give me 20. Did or didn’t you like the show? What are you trying to say?”

TH: Given your time in Chicago and how it has changed, what was the impact of the New Art Examiner folding as you saw it? How did that change the dialogue happening in the city?

HW: There are so many subtleties to that. The New Art Examiner has its own history and its role was to cover things in Texas, Georgia, the south east, etc. And for a specific window in the mid ‘80s, it was at its peak of readership nationally. As much as it was a Chicago institution, it was also national. It was here. This was its locus, but its coverage extended [beyond here]. New Art Examiner was the grande dame of regionalist arts coverage, in some sense.

TH: Regionalist but not quite regionalist.

HW: Right. It was a place where people could cut their teeth. There were editors, so it served as a kind of boot camp. [I was able] to watch the landscape shift and change, so when the New Art Examiner folded, it was due to print media in the face of the internet juggernaut.

The lifecycle of something like New Art Examiner, in and of itself, was an issue. Then there’s the issue of regional coverage. [There was] Alan Artner for Chicago Tribune. There was the Reader, which wasn’t visual art friendly at the time, focusing mostly music and theater. Newcity was art friendly.

But with the publication cycle and press coverage, I felt you needed to take matters into your own hands. [This meant] not just writing a press release and issuing it, but not waiting for someone to interpret the show. I started to write, in-house [at the Renaissance Society], about what was going on with the shows. Period. If you thought the press was going to be your output, [that probably wasn’t going to happen].

[For instance], the Ren has thousands on its hard mailing list. We realized that more of the people who are on that mailing list are our audience. Our shows were not [always] going to get reviewed in the Tribune, so we thought, “We’ll just do it.” That’s what led to the development of the essays in the posters [that were sent to our mailing list]. And that was a response to a really specific landscape. And it was functional. When nobody knew who Luc Tuymans was, [we wrote about him].

TH: That makes complete sense. And now those essays have been a consistent part of the Ren even with the move into a kind of internet domination. And your mailing list–has that audience shifted? Or have they remained consistent in wanting physical materials?

HW: Yes. Even ten years ago, I would argue, when others started sending out notifications saying “We are going all electronic. Do you want to continue to get mail?”, we never did that. We wanted to give [the posters] away. There’s no real reason to hang on to the poster other than that, by today’s standards, it’s a work of art. It’s a space onto itself. Even if it was functional, I always thought of it as a platform and gave it over to artists.

We [at the Renaissance Society] never really believed in branding. And we never assumed that anyone would come down to see our show just because the Renaissance Society said so. But now people think, “Oh, they’re showing it. It must have some value.” Before, we could never make that assumption, especially when we were doing events where only two people would show up. You had to fight and make an argument for what makes this work important and why [someone] should get on the goddamn Jeffrey Express to come and see it.

TH: Do you feel like over the years a trust has been built in the Renaissance Society and its work?

HW: Yea, the brand’s got equity. There isn’t the same kind of pressure to say what you’ll see when you come.

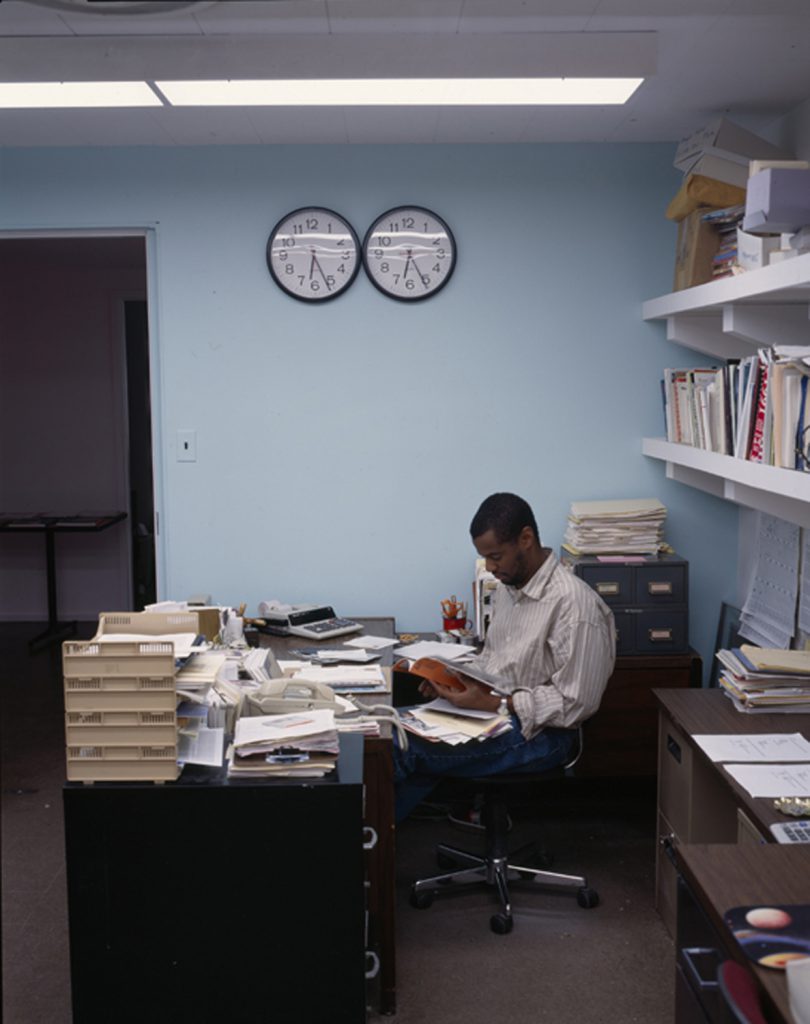

TH: So, between Urban Gateways and taking the position at the Renaissance Society, you worked for the Public Art Program?

HW: I worked for the city (Department of Cultural Affairs) as a Public Art Coordinator for almost four years. It was autonomous at the time, then it got folded into the visual arts. I was brought on to administer the Percent-for-art Ordinance for a series of branch libraries built in the wake of the Harold Washington Library. The two coordinators at the time, Stephen Mitchell and Mike Lash, were working full time on the Harold Washington Library. I was only working part time on Harold Washington Library and spent the rest of my time working on the branch libraries.

TH: The library has an incredible art collection.

HW: Yea. I was going to studio visits with Mike to make the selections of which portable pieces they would purchase. I remember Jacob Lawrence installing the mural and falling asleep as they were installing it [laughs]. These were major public commissions. I did the Chicago Authors Room. [I worked with] Tim Rollins on that. Because I worked at Urban Gateways, I knew the arts education people. [Mike] told me to take this project to Rollins who was showing at Rhona Hoffman Gallery at the time. To get the high school students who would work with Tim Rollins and Kids of Survival (KOS) members to make art for the reading room, we did an open call, surveyed a number of portfolios, came up with [a list of] about 14 kids.

Then, because I did that, I became the architect of Gallery 37 when it opened. Figuring out how Gallery 37 would work–that was my job. The day it opened, I was relieved from duty. [I was chosen to develop it] because I had dealt with the Board of Education when working with Tim Rollins.

Lois Weisberg wanted [Gallery 37] to include kids from all around the city and all walks of life. She wanted to put up tents, and show the work in the tents. Then, she wanted us to have the kids paint the tents. [During a meeting on day one] I spoke up and said we weren’t going to paint the tents. She looked out at me–I was all the way at the other end [of the room]–and she said, “Who are you? Do you work for me?” Everyone laughed. I did not know the protocol. I didn’t know that you do not tell a commissioner “No”. And you certainly don’t tell her “no” during a major meeting when she’s unveiling a plan. [laughs]

After that, I was going to move to Los Angeles–after college, whatever that means.

TH: But then what happened?

HW: I got the job at the Renaissance Society.

TH: Why were you focused on Los Angeles?

HW: Because of Mike Kelley. The energy in LA was so good. The Mike Kelley show at the Renaissance Society had just happened in ‘88 while I was an undergraduate. Everything in LA just seemed so magical. It was shit from childhood, and as far away from Baltimore as I could get. It had CalArts and [John] Baldessari. It had an aura.

I was going to head out there. Then, in ‘92 there was the Rodney King beating–I remember all that. I remember Mary Murphy and I were in a cab and the verdict was delivered. At the time I was volunteering for Randolph Street Gallery. And she was like, “You might want to think about your plans of going to LA.” And I thought to myself, “Damn, that’s true.” But that’s to say that as early as ‘92–I having been at the Department of Cultural Affairs for two years–I must have seen that my time at the city would wind down. Certainly by ‘93 I knew. By ‘94, I was ready to go [to LA].

TH: When you landed at the Ren, what art was happening on the South Side of Chicago? What landscape were you entering into?

HW: That’s a very complicated set of questions. I would rephrase or reframe it–since you said “on the South Side”–that means Black Chicago.

I’d worked for the city, so I knew about Africobra, Preston Jackson, Margaret Burroughs, Marcus Akinlana, and John Bankston. Kerry [James Marshall] had just moved here. Martin Puryear was here, but he left around that same time. Madeline Murphy Rabb, who was commissioner before Lois Weisberg, I knew her. Amina Dickerson was at the DuSable Museum and was friends with Ronne Hartfield. As far as cultural figures go, there was Beryl Wright, who was the curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art who committed suicide. Kerry did the painting of her. It’s so beautiful. (I don’t know if the MCA bought that painting, or if someone in Chicago bought that painting but it should be here, it should be there. It should hang at the MCA–they should own that painting.)

So, there was a constellation. The rhetoric of multiculturalism was in full swing [in the ‘90s]. It was all going down in New York. Chicago was wrapped up in a different dialogues that seemed like a holdover from the ‘70s. But in New York there was Glenn [Ligon], Lorna [Simpson], Gary [Simmons], Thelma [Golden]–that was all New York.

Then, generationally, age-wise, and as someone from the east coast, I always felt [different]. That’s why I moved to Pilsen and not the South Side. I cast my lot with that immigrant group. I had a really complicated relationship to Black Chicago. It was one not mediated through family. I’m not from here. I’m from Baltimore, and I’m actually not from Baltimore–I’m from New York. I’m from Baltimore insofar as my mom, my sister, my grandma and great grandma–four generations of women–are from Baltimore. I wasn’t born there, but my family was from there.

Chicago is a different city if you come in from somewhere else. I’m not connected [in the same way] to the Black Chicago machinery. When I worked for the city on projects on the South Side, people would always say, “You’re not from around here, are you?”

TH: Have you ever called yourself a Chicagoan?

HW: Only when I leave. Professionally. I have to represent when I have to do things and go places. At a National Endowment for the Arts or USA Fellowship panel, I represent the midwest.

TH: Going into somewhere like the Renaissance Society, which has an international scope, makes for an interesting positioning of yourself when considering what the landscape of the South Side was at that time. Did you feel the need to connect locally?

HW: No. I went to University of Chicago. I was going to the Ren while I was in college. At that time, I was a hopeful synonymy. When I interviewed with Susanne [Ghez] at the Ren, I knew about the Victor Burgin show, the New Sculpture show. I was a member in good standing when I interviewed. I didn’t know what it was when I was in college, I just knew they did interesting things. I liked it truly for what it was. I liked it not for the international reputation or scope at all, but because the exhibitions made me come back. I was curious [about work I didn’t get]. I found myself being more interested in that than in art I could get. There are a lot of ways to plug into the contemporary.

TH: Through that lens, you entered in as Director of Education.

HW: I resisted having a curator title for at least seven years. I was on the exhibitions committee at Randolph Street Gallery, so I didn’t have any anxiety around the title. If I wanted to do shows, I could do shows over there. [The title] didn’t matter to me. And I like the idea of creating the position of Director of Education, considering the rhetoric of multiculturalism and the number of Black faces in education departments and museums nationwide. Whatever I wanted to make of this, I could make of this. It was liberating to ask what educational programming could be for contemporary art. What do you do if you don’t have a collection? How do you contextualize work more socially, perhaps, than art historically? I didn’t feel beholden. I knew they didn’t have an identity problem, they had a PR problem. I knew that coming through the door. I knew what the University of Chicago environment was. I didn’t know shit about the rest of the South Side–actually I did since I worked at Urban Gateways and the city. I knew it geographically. But I wanted to start with the people across the street [of the Renaissance Society]. I’m talking about campus. [After that], then we could branch out to the neighborhood. That was more of the approach and spirit.

Outside of campus I visited Isobel Neal Gallery in River North. She used to have shows of the Black masters. That was the only gallery showing Black masters–Jacob Lawrence, Norman Lewis. At the [Chicago] Cultural Center I saw the Martin Puryear show, a phenomenal show. And there was the DuSable Museum. [At the time], I wasn’t interested in DuSable, and I still have my own thoughts about it relative to somewhere like the Studio Museum in Harlem. They stick to being a history museum who might engage in material cultural. But I don’t care what you are, you’ve got to do something more dynamic. There’s a lot to talk about.

My racial orientation with respect to art at that time could best be described as hopelessly queer. I’d seen enough of an ilk of Black romanticism that goes on without end. But that was me younger and angrier. Now, I have a more judicious way of thinking. At the time, relative to an ‘80s emergent politic and generationally, I knew that was over.

TH: I think you can recognize it while simultaneously realizing that it’s not for you or what you’re interested in exploring. I agree with you on many of those points. But it’s a matter of where your curiosity lies. It’s interesting to me how you escape the pressure to fall into being on the South Side around the strong presence of that work, and not feeling obligated to it.

HW: I didn’t have exposure to it. And I was far more headstrong at twenty than that work and whatever its mandates were. I’m a post-Civil Rights child. History, I love it. But I’ve got to be free now. I had a level of productive anti-essentialism.

Even still, when Kerry [James Marshall] came [to Chicago] I was down with that out-the-box. I remember Susanne putting images of Kara Walker in front of me and asking, “What do you think of this?” and I’d say, “I love it!” [laughs] It was a picture in a pamphlet from a show she did at Bard. The piece was of this young Black man with a huge erection, like a balloon, and he was floating up. It was a black cutout. It was so funny. I saw a level of irreverence, I understood it. It was like, “Finally.”

But at the same time, you also have to realize that that work wasn’t strong enough for me. The discourse and dialogue coming out of New York and the east coast around multiculturalism was more for me. I was here and it was there.

I was about 28 when I took the job at the Renaissance Society. The ‘93 [Whitney] Biennial went down. I was just reading about things like that in magazines. I never imagined that by 29 or 30 people like Glenn Ligon or Lorna Simpson [who were in these shows] would become my friends or that I would ever meet any of these people. I put emphasis on that because it says something about the scope of activity as I understood it and the nature of the hereness of the Renaissance Society. There was a whole other set of cultural politics going on in my head, and that’s how far away that was from me. They were famous, in magazines, in museum shows. I thought I would never meet these people. There was no Black Artist Retreat. [laughs] How was I going to meet them? I was so squarely here and not ever going to be there or participate in that dialogue. It wasn’t imaginable to me that through some slight-of-hand that that that would come to pass. I was just here doing my job. It did not go past the city limits. I was doing it for people from around the way. I was involved in the local art scene [in other ways], which was also nurturing for me.

TH: You mean when you were at Randolph Street Gallery?

HW: Yes. At that time, I’m hard pressed to list Black artists around the early 1990s. Chicago had folk art–William Dawson and Joseph Yoakum. And there were other artists here working, but they were working much more in a community arts beat, and hopelessly romantic. They weren’t participating in this larger discourse and dialogue. From my perspective, it was pretty blique. But I was not in that world.

But Theaster [Gates], he was into poetry, Afrocentricity, Love Jones, all of that shit. Poetry slams. The Green Mill. Youthful expressions of identity for me were really hackney, but necessary. It was not something that can be taken up in a solo sense by one artist. It almost has to be done collectively if we’re going to get into a dialogue about who we want to be or representation with degrees of complexity. Any kind of cultural essentialism is a project, and one that I think is underway still. It’s a project–not a piece of art. It involves producers, audience, but it has to heat up and get discursive. I felt it was going on, but outside [of my realm].

TH: Can you talk more about your relationship to music? Who were you listening to, where were you going to hear music in the city?

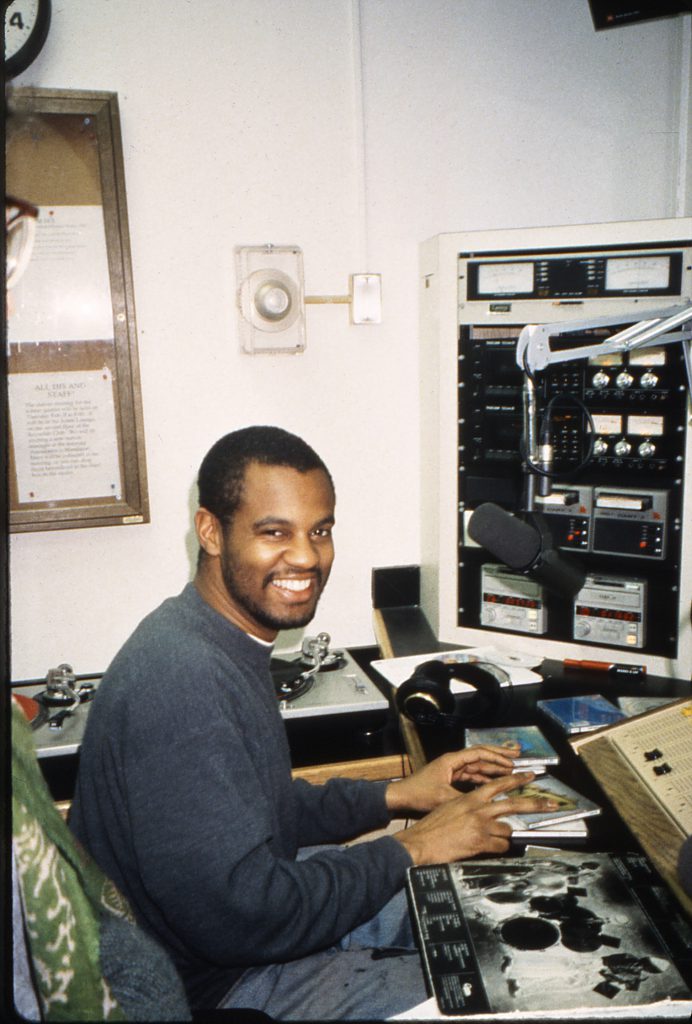

HW: Jazz, that was my thing. Culturally, that was my guide and what sustained me as far as Black cultural production here. My father was a musician, so I had a working knowledge of jazz. But I didn’t know about free jazz and [things like] the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM). I’d heard of Anthony Braxton. My father was friends with Archie Shepp and Gary Bartz, so I did know later day figures–but not the Chicago school. I had a radio show on WHPK in my last three years of college–my name was Mandrake. The show was Wednesdays and Sundays–different slots over the years.

During that time, I met Lawrence Rock and Leo Krumpholz–the guys who founded Southend Music Works. Somehow, somewhere in there, even before meeting them, I was quite conservative in my tastes.

TH: What do you mean by conservative?

HW: In terms of jazz beyond Ornette Coleman, my knowledge of free jazz was shaky. Some of my knowledge was self-initiated, so I spent a lot of time in libraries reading liner notes and looking for things to play. But some of it was from Lawrence and Leo.

I remember Kahil El’Zabar came into the station with Leo once. It was right after the release of Another Kind of Groove with Billy Bang [and Malachi Favors]. Orchestra Infinity–I saw them at Heroes one night. Rita Warford was on vocals.

It’s such a constellation of people and places. Sophia, [a friend at University of Chicago], knew about the Village Compound, which was on 71st. And Marguerite Horberg had a place–HotHouse–and before that it was called Salon Moda. These were all places [I would go to see shows]. But before that, I knew about the AACM historically. I had absorbed and taken in [their music]. But Leo and Lawrence started Southend Music Works, the Nomads of Modern Music. I volunteered and joined them after their first few shows.

So, [I was] volunteering for an arts organization, moving around to gigs at Columbia College or the Elbow Room, and meeting some incredible figures. Leo brought in a later day, European free-jazz elite and mixed it up with the local AACM scene. And also with a healthy dose of world music. Such amazing concerts–the list scares me. In terms of a sense of agency within the cultural scene, that was it. [It showed me how] someone could make a difference.

TH: You were doing this while at Urban Gateways?

HW: Yes, I was at Urban Gateways during the day. I remember sneaking Leo in and letting him use the Xerox and postage machines. [laughs] We would go out and pick up musicians from the airport. Musicians would crash at my apartment. I was really hands-on and making posters for a gig at the Elbow Room for Peter Brötzmann, Sonny Sharrock or Aki Takase.

There was also contemporary chamber music, classical stuff. I befriended Gene Coleman, a bass clarinet player in Ensemble Amnesia. And because I knew the free jazz side of things, Gene taught me about 20th century classical music. It was through [my relationship with] him that I came to develop the music program at the Renaissance Society. He was my eyes and ears on the ground, traveling through Europe and suggesting people for me to listen to. I met him through Southend Music Works. Then, I would spend my money at Rose Records and Jazz Record Mart. That’s how I got to know Chicago.

TH: What was the difference for you between the music and the visual? It seems like you were drawn to the ways music can have a much broader sphere of influence and pull from global styles in a way that the visual sometimes struggles to. Music is perhaps not as weighted by…

HW: Cultural specificity? Having a father who is a musician made music a default. I grew up in a perfectly fine upper-lower class community [laughs] We were poor and no stranger to government butter, cheese, and food stamps–just to set the record straight. But it was a proud Black nationalist home. I was a dashiki-wearing child. With my name, how could I not be? That was never in question.

But on another note, I was weaned on the rhetoric of anti-essentialism, which is different than a Black national cultural essentialism. I always keep those two things separate. So, ideas of self-determination and giving expression and form to a kind of relatively new, emergent, post-Civil Rights Black subject–that was the agenda. It wasn’t essentialism that was the problem. This would, still, put me on the outs with respect to the rhetoric of multiculturalism and a certain set of identity politics well into the ‘90s. Having been raised, in some sense, on an anti-essentialist rhetoric, the question of who or what one is or who/what one wants to be is a question without an answer. I mean, you can be whatever you want to be, but the idea to keep it as a question as opposed to an assertion as an answer was all to lay claim to a retooled African aesthetic. As visual tropes, it became, in some senses, somewhat easy. I wanted something more. I was after something [else].

Now, I’m older and it’s a matter of history. I’m now understanding what that work was and what it was trying to do at that time. I understand it for what it is. I’m coming to appreciate it on those terms, squarely. There’s what it was, what it was doing, and what I wanted when I was growing up. And what it was doing when I was that age, it was not measuring up to the world that I saw opening up in front of me.

TH: Around the time that you were starting at the Renaissance Society, there were some pretty significant shows happening–like the one at the Whitney, curated by Thelma Golden–Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary American Art. Did you see it?

HW: Yea, I saw it.

TH: What were your thoughts about it at that time, given where your thinking was?

HW: It was very complicated. I didn’t understand the gravity of the exhibition at the time. It was the first time I would see Barkley Hendricks’ work. Glenn Ligon’s response to Robert Maplethorpe [was] incredible, Lyle Ashton Harris’ response to Robert Maplethorpe [was] incredible. These were the works that stayed with me. The most interesting thing that I took away wasn’t the affirmational tone of it, or the tone of victimization or underrepresentation. The show was doing a lot of things and included work that came across on all of those registers. But the work that stayed with me was Lyle and Glenn in terms of race and sexuality. That opened the show up. They gave it another tone. The way it was critiquing representation–specifically with Maplethorpe.

The fact that that show was the first, and that it could be connected with Harlem On My Mind [at the Met]. [It showed that] history is still being made in terms of types of shows and kinds of shows that are really watershed and firsts. I didn’t understand that when I saw it. I mean, it was just on the eve of the OJ [Simpson] verdict and after Rodney King. So, I think my response, the highest praise I could give the show is to understand that at that time, more than a value judgement, it was hitting me at a really complex set of registers. It did stand out.

So, that’s where Black Male fell. I wouldn’t meet Thelma [Golden] until years later. The Black New York culturati seemed so amazing and distant to me.

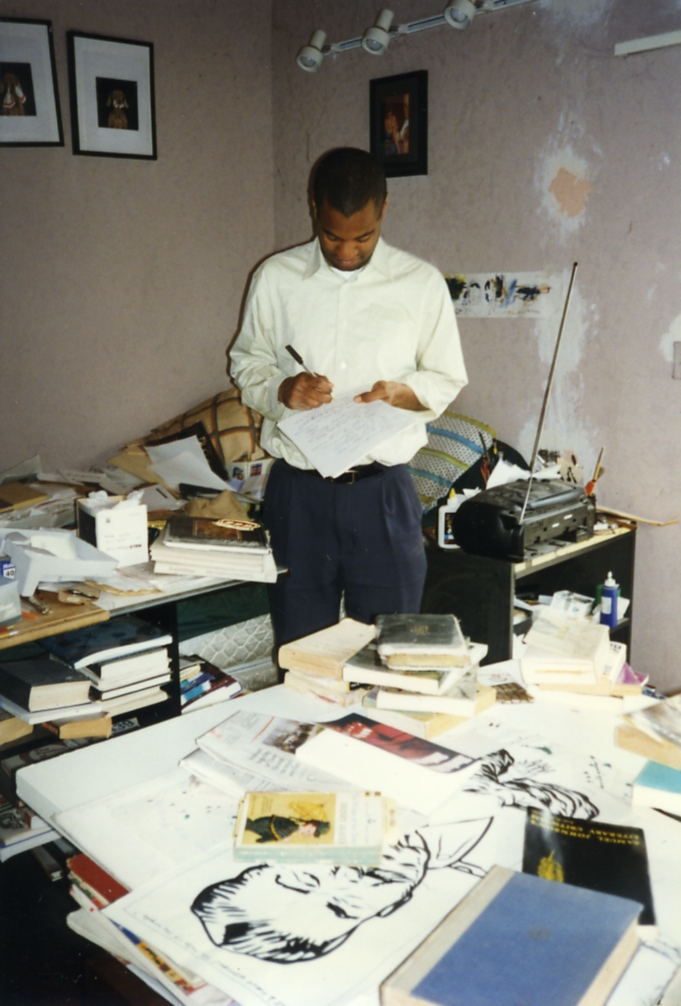

TH: So, you were seeing shows, meeting artists, but also doing a lot of writing as Director of Education…

HW: Yes, and thinking about the graphic identity, events, public programs, and publications. It’s a non-collecting place. So, [I was questioning] how to contextualize art being made now. I was crafting a kind of education on what a work of art has to say about living now. To talk about the legibility of the present is to talk about the newspaper. But, I was questioning if there are things outside of that information that art can reveal. That’s assuming that the present can be made legible. That’s a question. Can it? And can it be done so through a work of art? And does the work of art privilege legibility? Contextualizing the art socially and art historically [was my work]. What does it say to the last canonical movements–minimalism and conceptual art? That was the goal of the essays I was writing.

Because of Susanne, I had a director title. And all full of piss and vinegar, I could dig in. No one was stopping me. Susanne let me have 1000 words, 1,500 words–whatever I wanted. I was so much more invested in the local–that’s who I was talking to. The main thing was to keep the shit local. And even though the essays were going out to our mailing list [globally], everything was here.

TH: How did you keep a locally-minded voice through the writing, since it was being exported globally? How did you think about your language?

HW: I used plain-speak. If I wanted to get into post-structuralism and [my audience] didn’t know what structuralism was, I needed to be able to explain what it was. And I would say, “Oh! Structuralism. These are the implications of what structuralism is–the deep structures of the mind are thought to be wrapped up in language. And that would allow a certain set of anthropologists to start to talk about universality and they would find these things in children’s stories, folk tales, etc.” You have to be able to square your terms. And if you can’t square your terms, then do you know what you’re talking about? What constitutes coming correct is approaching somebody in plain speech. You can build the case so that by the time you’re ready to drop that word, you can drop it. Now that you’ve introduced it into the conversation, there’s an inherent pause where you should be able to have and go back [to your reader] and say, “You follow me?” This was very much a product of [Chicago]. Susanne was picking the artist and taking me on studio visits, and I had full access. So, those people were my friends. People like Luc Tuymans and Diana Thater were my friends.

And I was amusing myself. I was my primary audience. All coked up on Starbucks, late all the time and burnt out from it.

TH: How did you develop your curatorial voice?

HW: There’s no such thing as that. I don’t believe in that. You do shows, you work with artists. I volunteered for Randolph Street Gallery, and they never called anyone a curator. They would say, “exhibition organized by…” They never liked the term curator because it was authoritative. I inherited that. It was more about the exhibitions committee. I was just the organizer, I wasn’t the curator.

You had input from other people. And they didn’t do solo exhibitions. They only did thematic, group exhibitions. So, for me, exhibitions were meant to be thematic. Doing a show meant a group show. That was the default.

It was not a privileged activity for me. The ethos of it was always about presenting the work in the least mediated fashion. And if it was good, you didn’t give a fuck, period. It was about presenting work you believed in–that’s all. And you were doing it with others. So, we believed in the work and we hoped you did too. The idea of a curator and the division between the audience and curator [didn’t exist]. It was a different era, a different time, a different moment. So, the early group shows at the Renaissance Society, that’s what I knew curating to be.

The writing and studio visits with Susanne was a form of curatorial labor. She chose the artists, but I would write about them. So, then who’s the curator, what’s the curator, and what’s the curator’s voice? Well, I’m giving voice institutionally on what the show is about but Susanne is the curator. The idea of a vision and a style, there’s no “me” in it.

And in terms of it being a curatorial practice, fuck that! This is a job! [laughs] Practice my ass. With all the hoops and hurdles that come with it, the shit costs money. It takes resources. When someone’s about to drop ten thousand dollars, at that level you’ve got to earn it, raise it, figure out what to spend it on–that is a job. Practice is work.

TH: How did you come into the curator title?

HW: It came about because Susanne got tapped to do Documenta. By ‘99 or 2000, Susanne was on the road in India and China, and couldn’t be as present on the floor [at the Renaissance Society]. She noticed that I’d been running around the city [doing shows] and she’d seen the show I had done at the old Hyde Park Art Center in the Del Prado with Simparch, called Free Basin–a skate project with Matt Lynch and Steve Badgett.

TH: Tell me about Free Basin.

HW: At the end of a trip to New Mexico and on the way to the airport, my friend’s boyfriend took me to a warehouse. I didn’t know where I was. When I walked in, someone jumped down from a platform on a ramp, on a skateboard. I had walked into the middle of ramps where the skaters would criss cross. When I came back, I said that we should do a skate bowl.

It was just for the skaters. And it was before they built all the skate parks around the city. Supreme–the skate store in Los Angeles, Tokyo, New York–they own that skate bowl and made the final resting place of the piece their store in LA. That was a big one. Then it went to Documenta in 2002.

In 2001, I did another piece with Simparch, a sound piece called Spec: An Electro-Acoustic Investigation. We commissioned Kevin Drumm to make a composition. They made the gallery acoustically viable. And that one, too, went to Documenta.

TH: Let’s fast forward to when you did Black Is, Black Ain’t (2008). Did you know it was going to hold as many tensions as it did with it being a show that was a direct reflection of the expanded way you viewed Blackness? It makes complete sense now knowing your personal ethos on anti-essentialism.

HW: That show is becoming increasingly biographical for me. It has a lot to do with understanding something that we all think we understand: race. What do we mean when we talk about race? Things are always changing. In my life, my parents’ lives, my grandparents’ lives, society. It’s easy to say, “Ain’t a damn thing changed.” But how did you learn race? You were taught in school. And what was that built on? What is this thing that we make up and abide by?

In that window [of time], there was plenty of work made that played with race in interesting ways and in a way that’s not resolvable. But we still think we know what it is. Then, when there’s a show of Black artists people think it’s about race when it’s actually not. It’s just a show of black artists. [I wanted to call out] the lopsided nature of the subject.

I remember an older woman came to the exhibition talk and told me, “Where’s the ‘is’? I don’t see the ‘is.’” I’m bothered by that even to this day because I now understand what she was looking for–as far as essentialism and non-essentialism. I had a much more ironic tone about the ‘is’. I now joke with Theaster [Gates] about how to be the ‘is.’

Then there’s play. People saw the show and said that it was so much fun. People figured that when I said I was doing a show about race that it would have a serious tone. But I was having fun, and that’s how I went into it. I didn’t realize what it originally sounded like at all.

TH: I find that to be really important way to approach that subject matter. It goes back to what you were saying about Black Romantic and perhaps how we have been trained to read and express the work of Black artists or on Blackness for so long. The fact that people are able to move outside and away from that, particularly in this show, my mind goes back to music and how it’s so flexible and able to absorb and expand without having to remain in a certain genre and speak to specific histories, techniques, audiences. It’s happy to say, we’re starting here and going in this completely different direction.

HW: Yea, and that’s the thing of joy. It’s a riddle. If you can stay at the level of the riddle, it’s great. And looking [at things as] one of many possibilities. You want to stay in the riddle phase. But also, there’s a beautiful and warm reaction. Even the idea of getting [or understanding] something. Black Is, Black Ain’t wasn’t about getting it. People were enjoying themselves. It was fun. I had as much fun doing it. But the show after that was better.

TH: Which show?

HW: Several Silences (2009) was better. Black Is, Black Ain’t was a generous show with a lot of work. And it had its own architecture. But Several Silences was pure architecture. There were fewer points, and there could be fewer points to describe a certain structure. Like a wine–you have wines that can power through a grilled piece of meat. Then there are others that are built with an architecture that is lighter and airy–it just breathes. Black Is was a more solid kind of building. With Several Silences, everything turned around a single work, so the mapping was very clear.

In making an exhibition, you should do something that is smarter than you. I wanted [the show] to be built around symmetry and revolve around the individual pieces–with no fat. It was a counterpoint to the previous show. Why I feel better about it as a show is because I was wholly conscious and profoundly confident, which is a rarity for me. I could give a precise schematic of what I was going to do, and the results were so much more than what I was wholly conscious of.

Friends knew. They knew I stepped up into a whole different register of poetry and meaning. Usually people can understand and follow your dance steps, but I did a number and busted a move. [laughs] I’m really proud of that show. Then, there was Suicide Narcissus. I like the fact that they’re all temporary. If you saw them, you saw them.

TH: I don’t want to gloss over the past several years, but since then it seems like there has been a slow transition that now lands you in LA, just after working on Made In LA at the Hammer Museum with Aram Moshayedi. Did Made In LA kickstart a rekindled interest in LA, set the groundwork, and lead you to the path you’re on now?

HW: We’ll see. It’s a new terrain. We’ll see what survives and if I’ve learned anything or what things are useless there. [laughs] Made in LA was a different mandate. I was brought in to come and look at what was there right now. I wasn’t there to learn about LA art or be beholden to [its history]. There was no need to lapse back into a narrative about the city itself. All it was, at the end of the day, was some art. It’s really hard to resign yourself to that.

TH: And what’s your new mandate at LAXART as the Deputy Director and Curator?

HW: I don’t know yet. These are interesting times. I think I’d like to try my hand at responding to the here and now.

TH: And what does the here and now mean to you?

HW: This election means something. What exactly is something we are all figuring out in real-time. How things play themselves out in this context is a question that is hard to ignore. You can do all kinds of things–maybe you would do the same thing with or without the election, and it doesn’t matter. But I would still argue that even if it’s the same program, there’s a different figure/ground relationship. We’re on a different ground.

How contemporary can contemporary art be? Can we ask it to respond to this situation? To be so bold is to do so. Sometimes I think maybe we should back away. You either back away or double down and make a bigger commitment. But let’s be bold. Some pretty big shit just went down and if you were ever going to have a reason to be bold, I would make the claim that this is that reason. And to not be afraid.

TH: So, now you’re packing up. Your connections to Chicago are pretty thick, and it’s been a long run of nurturing those roots. I’m curious if you think there is anything that Chicago gave you. And what is the theme of your Chicago chapter?

HW: I grew up here. It’s home in that way. There’s growing up between zero and 18, then there’s growing up professionally. This is where I learned how to do things with a community of people that were encouraging and supportive of me doing those things. This is a place that does allow you to dream and scheme. Chicago was a place that could indulge me. I could do things with my immediate community–like insisting that everyone who wrote for Black Is, Black Ain’t catalog be from Chicago. I could do things from here and for us. And to feel like what we do from here, for us, can be significant in a broader context.

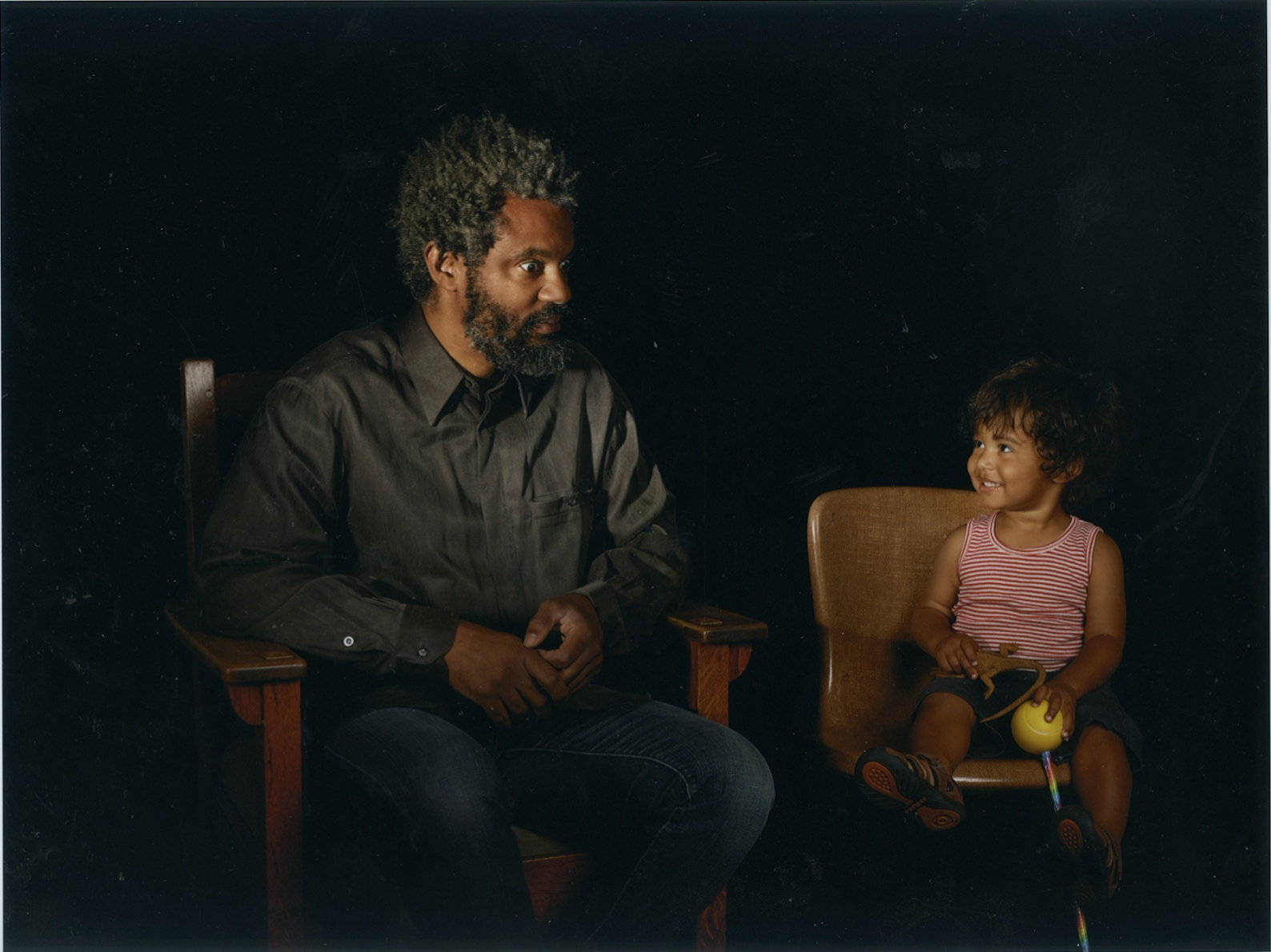

Featured Image: Portrait of Hamza Walker, courtesy of the Renaissance Society.

Tempestt Hazel is a curator, writer, and founding editor of Sixty Inches From Center. Her writing has been published in the Support Networks: Chicago Social Practice History Series, Contact Sheet: Light Work Annual, Unfurling: Explorations In Art, Activism and Archiving, on Artslant, as well as various monographs of artists and exhibition catalogues. tempestthazel.com

Tempestt Hazel is a curator, writer, and founding editor of Sixty Inches From Center. Her writing has been published in the Support Networks: Chicago Social Practice History Series, Contact Sheet: Light Work Annual, Unfurling: Explorations In Art, Activism and Archiving, on Artslant, as well as various monographs of artists and exhibition catalogues. tempestthazel.com