The following are reflections and suggested sounds for pieces by seven artists that were included in the exhibition ALL WE WANT IS TO SEE OURSELVES at FLXST Contemporary. The exhibition ran from August 3 – September 1, 2019 and was curated by Jan Christian Bernabe

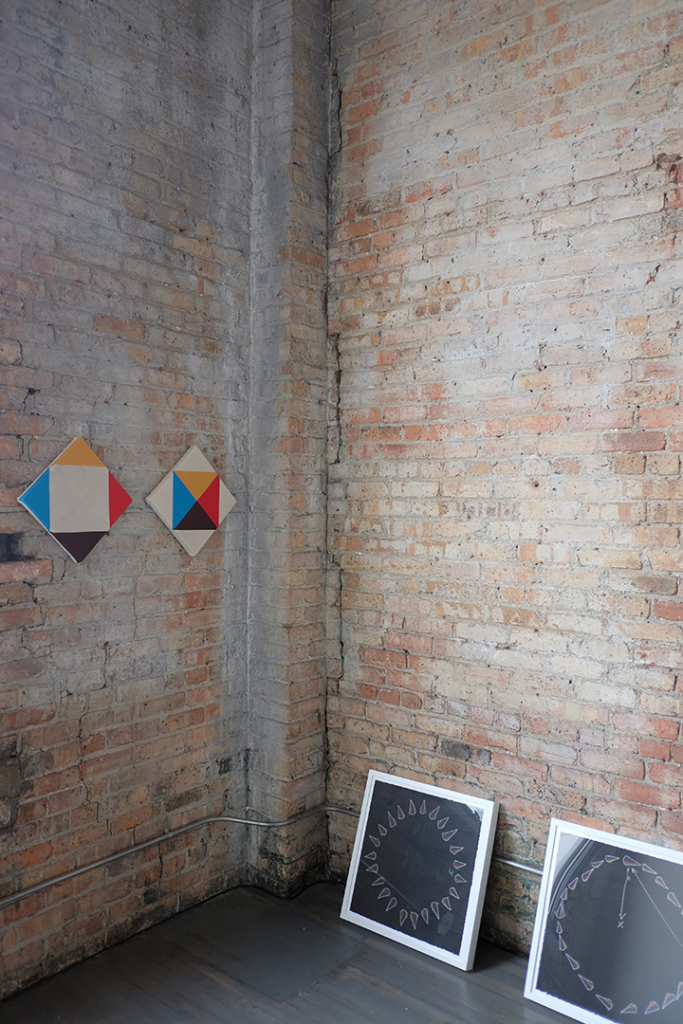

Paolo Arao, Greater Than (Diptych), 2018

Greater Than (Diptych) splits into two canvases hung like diamonds, each one broken down by the same primary colors: blue, red, yellow, and beige cotton. On the left canvas, the corners each have a perfect triangle of either blue, red, or yellow while in the center lies a perfect beige square. On the right, the same color pattern is inverted: four beige corners and a square divided into four slices of elementary colors.

Once you know the title, it all falls into place and the geometry, the hidden mathematics of artifice, begin to open themselves up. An elementary school teacher taught me that the greater-than sign could be remembered because the alligator (> or <) eats the bigger number (the better number?) and here, the alligators are everywhere, pointing you back and forth between canvases. You impose the outline of the canvas as the outside of the canvas and difference as a marker of quality as the artist knows and suggests.

Do you take the hint? Or do you trust alligators more than yourself?

(A person behind you claps 2×4 planks together at regular intervals of your discretion.)

Kelvin Burzon, LATEX: Heart and LATEX: Kidneys, 2019

I didn’t realize that Burzon’s photographed sculptures were made of latex. Before I formed that understanding, I had already decided that these meats looked delicious and if I were deserted in a house in an apocalyptic snowstorm with only the body of somebody I had never met before and if I were assured they were without disease, I would.

I would.

But LATEX, with its meat-stuff wrapped in condoms and stitched together by stray thread, evokes disease and microscope slides and hospitals looking at people’s bodies after the fact. ALL WE WANT IS TO SEE OURSELVES dissected and pulled apart for the good of science, even if wrapped in a body bag. This is the bitter humor that Burzon approaches us with. Centered with a black backdrop and surrounded by white, you’re viewing the diseased body like capitalism: a series of parts ready for consumption.

One way or another.

(Somebody smacks their lips about fifteen feet away from you.)

Roberto Jamora, Bayou St. Malo, Lake Borgne, and Manila Plaza, 2018

The lines curve and form rivers over the horizon and a geography of memory emerges from the river bed. The bayou flows and breathes. The lake looms and sees. And Manila Plaza thrives and beats drums. Jamora’s paintings work texturally. The bodies of water mentioned become crossroads of time and space, imprints of a history lying underneath dawns and dusks. Jamora’s trio acknowledges the multiplicity of identity and applies it to landscapes; this place is not only a river, but it is an ecosystem, a market, a disaster, a secret, the sacred. It’s difficult to not want to scratch the upper layer back to view the wholeness of the underimage.

But if you did, your nails would break and your fingers would bleed while the paint sits scattered at your feet. The canvas would be empty and there’d be nothing to do to bring it back. That’s not fair. So… don’t do it or promise to bring it back.

I dream of bringing it back.

(Somebody kicks a bucket and a leak drips into it. Ping.)

Kiam Marcelo Junio, Sheath (from the Dona Nobis Pacem series) and Pink Panagnip (from the Dona Nobis Pacem series), 2019

I’m staring and I know what I’m looking at. I have seen it before and yet it disorients me, it moves from under my feet. God, grant us… something. Am I praying? All of a sudden, I’m praying for something with something, but I’m not sure of what I’m praying about nor which words I’m using. I decide to leave the rest to God because they’ll have all the words.

You know what you’re looking at, but you can’t call it what it is because it disintegrates even as you put words to it. It’s a flower, it’s cheesecloth, but it’s also vanishing, jerking in and out of your view. You’re trying to hold onto it, trying to grapple with this image as temporary as milk, an orchid, a fraying sheet.

If you could collect yourself long enough, you’d remember their names.

(Faraway, a person folds a quilt.)

Kat Larson, Untitled (Dirt Painting), 2011

Untitled (Dirt Painting) is clean. The lines are sharp, the dirt is chocolate, and where there’s no dirt, there is a solid, sterile white. I look at this, I think of a grave, a temple, a city park, or the foundation of a building. It is the most explicitly political of the pieces. Which piece of the painting is foreground, which background?

Regardless, Larson’s painting leaves me dissatisfied; the lines are too clean. The dirt should be everywhere. Ev-er-y-where. It makes me want to make a garden, it makes me want to break the glass containing it and destroy the tidiness that should not exist. Maybe this is the point: that to separate the dirt is intrinsically destructive, extractive, and to manipulate the natural is an act of human, colonial pride that hollows us in the process.

I could swear that I’ve seen this painting before.

(You overhear a conversation in a garden. Cars.)

Gina Osterloh, Orifice, Holding Space (Blue), 2018 and Drop Shadow, 2014

Respectively, Orifice and Drop Shadow observe the macro and the micro, expanding and shrinking into the other until we understand how fractals work.

Orifice is a series of small black dots in an ultramarine background. At the center, the dots condense around a circle of that bluest blue. From far away, it resembles discolored dragon fruit flesh. If you get close, they’ll start to expand and you’ll wonder if they’re islands. You could fall into this painting. It wouldn’t be difficult. The center, the suggestion of shape opens wide and invites one.

Drop Shadow on the other hand breaks away from indicators of the natural and instead takes place in the corner of a bathroom. I don’t know for sure, but it reminds me of college drinking, staring over the toilet and into the tiled wall where the grouting begins to delineate, and when I get close enough I can see the grouting, a house millipede, and the floaters in my eyes. A universe unfolds in those tiles.

Osterloh makes good maps.

(A person sits, wringing a broad piece of paper. Close your eyes. Waves lap on a shore.)

Jeffrey Augustine Songco, Choreography Playbook no. 1 – 9, 2018

Chalk, it’s chalk. You remember middle school, maybe high school if they hadn’t switched over to whiteboard. Were you ever in a locker room waiting for a show? The lights, fluorescent melt over you while emaciating the faces of your team. There, that one: they work at an orchard in the summertime and bake pies in the winter. Next to them, that one likes to smoke weed and go for long runs. She parties hard, but works even harder. Me, I observe, listen, archive. We wait for our coach, I don’t remember his name, but I remember that they were a big deal for this theater maybe ten years ago. That’s all I know about them. When they arrive, they flip the chalkboard.

On it are a number of triangles, each containing a stripe of rainbows, arranged in a line from the top to the bottom, growing progressively smaller as they reach the bottom. Next to that line is an arrow pointing down. At the bottom, an arrow on either side directs the smallest triangles in a semi-circle back up to the top.

I’m on the field or the stage. The crowd looks at us. We’re all in uniform. We’re inseparable.

Looking at the piece, I empathize deeply with each of the triangles. I feel unique and just as brilliant as the other players and dancers. I move in line because my coach respects both my role as an individual and as a member of a collective. Some of these arrangements look like teeth, some like clocks, but all offer you the respect as a member of a movement. You deserve it.

(Glasses clinking together. On the count of three. One. Two. Three.)

Featured image: A fading brick wall and, running parallel to the wall, bluish-grey floorboards. To the right, a black backless bench. Behind the bench is a white wall with Kelvin Burzon’s LATEX: Kidneys and LATEX: Heart. Leaning up against the brick wall on the floor are eight pieces from Jeffrey Augustine Songco’s “Choreography Playbook” series in white frames. Image courtesy of FLXST Contemporary.

Persephone Jones is a writer, theater maker, and visual artist whose work focuses on the interaction between fiction and non-fiction; names and events as well as the contours of dreams against the material. They’re a contributing writer at NewcityStage and have worked with the Neo-Futurists, Facility, the Prop, (re)discover and TUTA.