Allison Lacher and Jeff Robinson work collaboratively as artist-curators and organizers in Springfield, Illinois. For over seven years, they have developed contemporary arts programming at the University of Illinois Springfield Visual Arts Gallery, DEMO Project, and the Terrain Biennial at Enos Park. Lacher and Robinson reached out to seven creative and cultural purveyors whom they have worked with over their tenure in the capital city to reflect on their experience there — that is to say, “here.” The resulting texts together form “You are Here,” a new venture from the collaborative duo in partnership with Sixty Regional and made possible with support from Illinois Humanities. As is typical of their curatorial approach, Lacher and Robinson have extended freedom and latitude to each contributor, resulting in texts that take a variety of forms and offer wide-ranging glimpses into what it is like to work here in the flyover region of the United States, in the perceived rural Midwest, in Central Illinois, and, at the heart, here in Springfield.

An Argument for Excavation

by Cass Davis

In 2017 I was invited by Greg Ruffing to create an outdoor installation for Terrain Biennial in Springfield, Illinois. The lot I chose reminded me of my childhood home in a number of ways. It rested in a quiet, historic neighborhood alongside railroad tracks, where time was marked by the passing of the occasional train that broke the silence of the small town. An empty site, it echoed the empty lot next to my childhood home whose wound in the earth spoke of a grave absence. This space also held unexcavated trauma for me. The chosen lot in Springfield had been the site of a home likely destroyed in the aftermath of the 1908 Springfield Race Riot.

The haunted emptiness of a lot that once held a home spoke louder to me than the archival photographs I found of the neighborhood that had just crumbled beneath clouds of billowing smoke. In the photographs, a seemingly innocent crowd of onlookers gazes at the wreckage and into the lens of the camera. To me, their witness is an act of indirect, but very real violence. The trauma of the Enos Park community was compressed into a newsworthy spectacle for the rest of Springfield—and the country—as the 1908 Springfield Race Riot became the catalyst for the formation of the NAACP. During my research into the State Archives in Springfield, I held in my hands disturbing postcards and “souvenirs”created around this event. I listened to cassette tapes that held the voices of individuals who had observed the event, the tactility of their voices translating material from their memory of 1908.

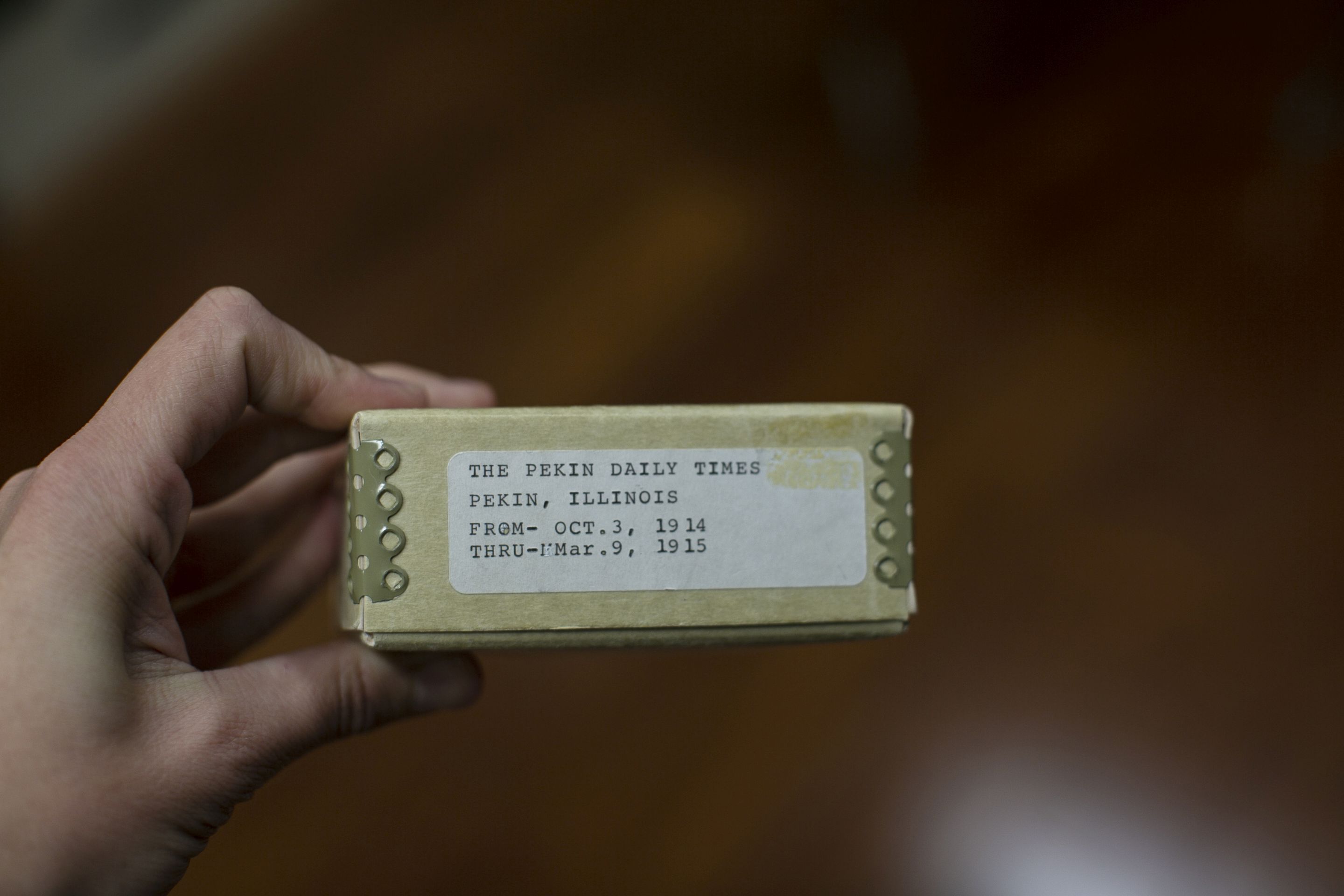

For my installation at the Terrain Biennial, I replicated one of the archival photographs in large scale and erected a form of its image in the empty lot in Enos Park. I wanted to speak to the phenomenological history of the space and to invite an echo of the community that once lived there but had been driven out. The lot was situated between two homes and was center stage to the regular passing of railroad train cars. The sound and presence of these train cars was nostalgic for me as they filled the background of the days and nights of my childhood in Pekin, Illinois. Pekin has a history marked with racism and an unresolved reputation as a Sundown Town until the late 1970s. I’ve spent a great deal of research working to uncover Pekin’s history in relation to racism and found that much of the archive is missing or hasn’t been recorded. The absences in the archive speak volumes. In the Midwest and across the nation, there is a burying and erasure of these histories before we’ve even been able to address them. Especially for Sundown Towns in the north, there is a misconception that our communities do not have important history to address in relation to racism.

In her text Ghostly Matters, Avery Gordon describes that which is quite intangible and seemingly impossible to locate: collective and personal trauma, buried deep within our histories and memories in such a way that we cannot look straight at it. She describes the kind of trauma that is unspeakable or that has been neglected and hidden for so long that we question if it ever happened. Was it as bad as we said or thought? Was it worse? How could that have been possible? On a biological level within our own bodies, trauma is stored in strange ways that often mean memories and events are buried deep in order to survive and move forward without entirely breaking down. In some ways it is a phenomenal adaptation that our brains, at times, literally forget certain events so well that traumatic childhood events can go unremembered until years into adulthood when something triggers the memory, or treatments like hypnosis bring lost memories to surface. It does beg the question then, how does one heal from trauma and find a way to move on?

Some remedy this by identifying the cause of the trauma that has occurred but this becomes difficult when the memory is lost, forgotten, or purposefully buried. This sort of “forced forgetting” is used to maintain control over the survivors and ensure those in power who have inflicted such violence stay in power. Avery Gordon talks about these sorts of buried traumas and how they function parallel to our personal experiences, but on large scale societal levels. She describes such lost memories functioning as ghosts or hauntings, speaking of them as a sort of presence. Gordon writes, “The ghost imports a charged strangeness into the place or sphere it is haunting; the ghost itself represents a symptom of what is missing and of a loss or path not taken, and then that ghost becomes alive.1” While we may not be able to access the original memory, there is a reverberation and sort of ripple that occurs in the trees and buildings and soil around us. There is a haunting of that memory. And essentially, by recognizing that haunting, we can identify to what it is pointing.

How is the haunting embodied in and conjured through material presence and human absence? How can we alter our perceptions of history? What if we recognize that the oppressed past is non-linear; that history remains alive in the present? Perhaps we can recognize that the ghosts that haunt our lives are speaking to us from the past—that through acknowledging their presence, we may find a place to address our history with honesty and find a path to healing. As Gordon reminds us, we must reckon with these ghosts, “We are in relation to it and…we must reckon with it graciously, attempting to offer it a hospitable memory out of concern for justice.2” The ghosts remain alive because their history is unacknowledged and unresolved. It is our due diligence to continue to question history and to fight for its complexity. We can only move forward when the past is acknowledged for what it truly is, no matter how painful those truths may be.

What does it mean to really confront, to really examine our collective trauma? Our own trauma?

Featured image: Image: Documentation image of Cass Davis’ Witness, 2017. The piece is made up of 30 hay bales, bailing twine, and an archival reproduction of a photograph from the 1908 Springfield Race Riot. The close-up shows details of the black and white archival photograph that has been enlarged, cut into smaller rectangles, re-pieced together, and strapped onto the face of a stack of hay bales with twine. Subjects in the image appear to be onlookers at the scene of a catastrophic event and several gaze at the camera. The documentation was taken at sunset, as the light fades. Documentation photo courtesy of the artist. Archival photograph courtesy of the University of Illinois, Springfield Archives.

Cass Davis is a Chicago-based artist with an MFA in Fiber and Material Studies from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Their solo shows include No Body on Earth But Yours in conjunction with the Chicago Underground Film Festival, and Of Roses and Jessamine at SUGS gallery in Chicago, with an upcoming solo show at G-CADD in St. Louis. Davis has shown in group exhibitions and screenings at York St. John University, UK, Tile Blush in Miami, FL, The Art Institute of Chicago, Museum of Contemporary Art, The American Medium in NYC, Terrain Biennial, Chicago Home Theater Festival, Mana Contemporary, Sullivan Galleries, and the Silent Funny in Chicago, IL. They have been awarded the Oxbow Summer Artist’s MFA Residency, Roger Brown Artist’s Residency, and the IOTO Summer Residency, Shapiro Center Eager Research Grant, the World Less Traveled Grant, Dean’s Merit Scholarship, and has been lecturing faculty in Fiber and Material Studies at SAIC. Davis is currently an artist in residence at the Chicago Artists Coalition as part of the HATCH program. Artist portrait by Gillian Fry.

Cass Davis is a Chicago-based artist with an MFA in Fiber and Material Studies from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Their solo shows include No Body on Earth But Yours in conjunction with the Chicago Underground Film Festival, and Of Roses and Jessamine at SUGS gallery in Chicago, with an upcoming solo show at G-CADD in St. Louis. Davis has shown in group exhibitions and screenings at York St. John University, UK, Tile Blush in Miami, FL, The Art Institute of Chicago, Museum of Contemporary Art, The American Medium in NYC, Terrain Biennial, Chicago Home Theater Festival, Mana Contemporary, Sullivan Galleries, and the Silent Funny in Chicago, IL. They have been awarded the Oxbow Summer Artist’s MFA Residency, Roger Brown Artist’s Residency, and the IOTO Summer Residency, Shapiro Center Eager Research Grant, the World Less Traveled Grant, Dean’s Merit Scholarship, and has been lecturing faculty in Fiber and Material Studies at SAIC. Davis is currently an artist in residence at the Chicago Artists Coalition as part of the HATCH program. Artist portrait by Gillian Fry.

1 , 2 Gordon, Avery. Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination.Minneapolis: U of Minnesota, 1997. Web.