Allison Lacher and Jeff Robinson work collaboratively as artist-curators and organizers in Springfield, Illinois. For over seven years, they have developed contemporary arts programming at the University of Illinois Springfield Visual Arts Gallery, DEMO Project, and the Terrain Biennial at Enos Park. Lacher and Robinson reached out to seven creative and cultural purveyors whom they have worked with over their tenure in the capital city to reflect on their experience there — that is to say, “here.” The resulting texts together form “You are Here,” a new venture from the collaborative duo in partnership with Sixty Regional and made possible with support from Illinois Humanities. As is typical of their curatorial approach, Lacher and Robinson have extended freedom and latitude to each contributor, resulting in texts that take a variety of forms and offer wide-ranging glimpses into what it is like to work here in the flyover region of the United States, in the perceived rural Midwest, in Central Illinois, and, at the heart, here in Springfield.

Auxetic Art Community

by Adam Farcus

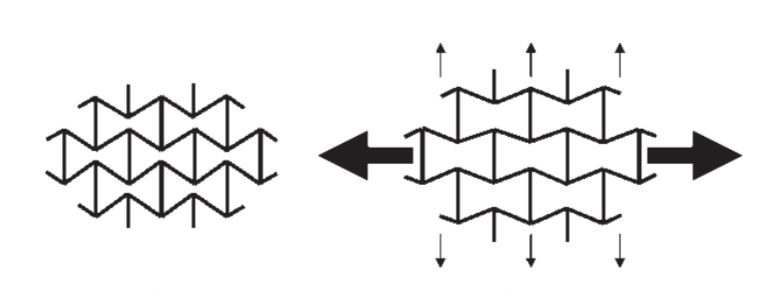

A cat’s skin, when stretched longitudinally, becomes thicker laterally. Cat skin is in a class of auxetic materials, which also includes salamander skin, cow teats, human tendons, cadmium crystals, cork, seat cushions, airplane wings, antibiotic-self-delivering bandages, shock-absorbers, and body armor. The structure of molecular or macroscopic auxetic materials offer mechanical properties of energy absorption and fracture resistance. Which means, when auxetic materials are stretched, under pressure, or otherwise ‘put to the test’, they become stronger and more responsive than non-auxetic materials.

The art community of central Illinois is a cat’s skin, and is akin to the art community structures found in other perceived rural areas. Baltimore city and county might be the body armor, the Mississippi delta region could be the shock-absorbers, and Wisconsin is definitely the cow’s teat. These areas are sometimes correctly defined as rural, but they also include college towns, suburbs, urban areas, and cities that are diminished when compared to New York, LA, or Chicago. In these three cities there is a wealth of privileges: large numbers of creative people, opportunities for art sales and public funding, geographic proximity, and many spaces to make and exhibit work. In perceived rural areas like central Illinois, the art community is stretched out through a large social and geographic area. This stretching of space and resources is what makes the central Illinois art community resilient. There is a formal and informal lattice-work of artists, curators, galleries, art centers, project spaces, and educational institutions that understand how their auxetic art community is maintained by their strong bonds to others and by the collective stretchiness required to meet the community needs.

Auxetic materials work because they are made of grid-like structures that look compressed in their un-stretched form. When force is applied to the grid, often a tessellating honeycomb, it looks less compressed and becomes more spacious. The intersecting points within the structure hold the honeycomb together. These points of intersection in the central Illinois art community are the stake-holders and institutions. Springfield, the knot of stretchy belly button skin on the central Illinois cat, is important not only because it is geographically central between Chicago and St. Louis, but because of local artists who are committed to the city and centers of artistic practice, including the now demolished DEMO Project, the Springfield Art Association, and the Visual Arts Department and Gallery at the University of Illinois, Springfield. These institutions on their own serve an important role in the city of Springfield, but their connections to other sites are of equal importance. Such sites include: Project 1612 (Peoria); the School of Art + Design at University of Illinois and the Krannert Art Museum (Champaign); The Freight House Exchange (El Paso); Heavy Brow (Bloomington); Illinois State University’s School of Art and University Galleries (Normal); the Art Department at Millikin University (Decatur); many other art centers, galleries, and programs; and institutions like the Illinois Art Council and Sixty Inches from Center that are committed to funding art (and art writing like this) in central Illinois. Also, it is inspiring to know that there are artists and mentors with thriving studios, such as Bill Conger’s studio in a century-old building in downtown Peoria, Jan Bandt’s converted space in Bloomington that functions as a site of creative production and public engagement, and Allison Lacher’s sub-division garages-turned-studio in Springfield.

Even though I no longer live in central Illinois, I still have a meaningful connection to the area. I have gained insight into the innerworkings of this auxetic art community through my experience as a BFA student at Illinois State University, a preparator at the McLean County Arts Center, a collaborator with area artists, an exhibitor at numerous central Illinois alternative and institutional galleries, and as a curator for a few different spaces (including my first and short-lived alternative gallery, Elder Space).

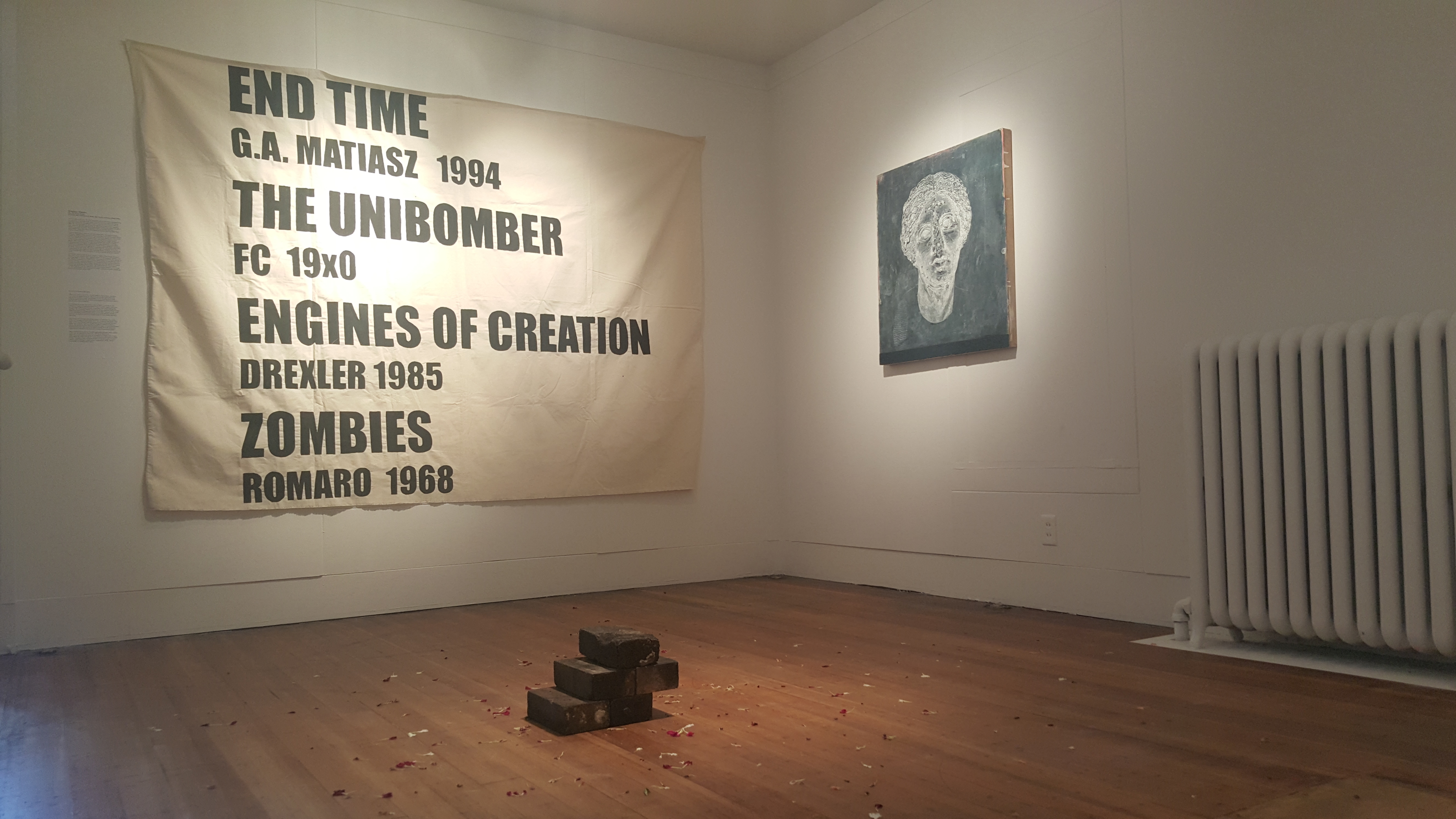

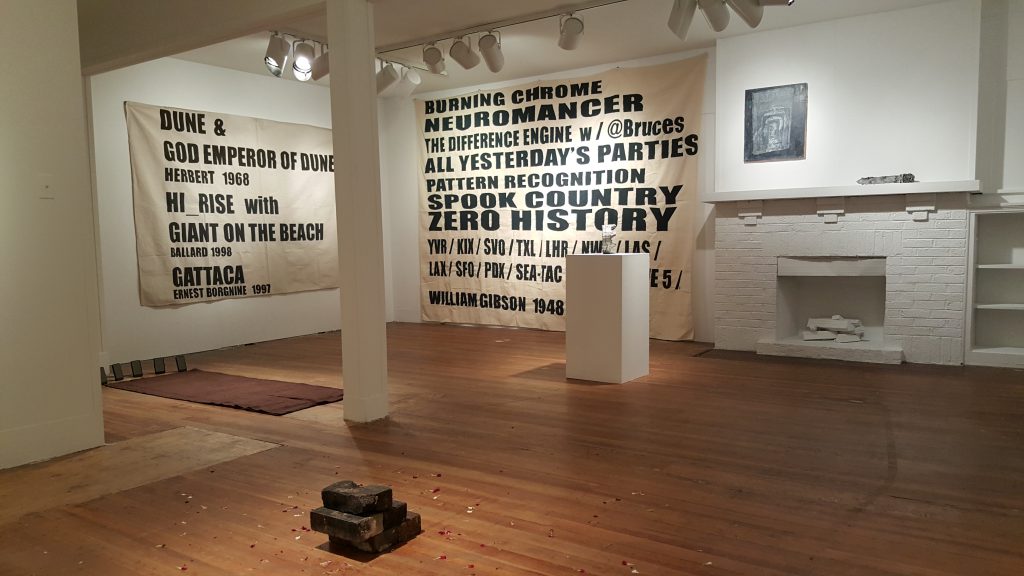

There is an assumption that perceived rural areas are not as rigorous and that expectations are lower than in the big cities. In contrast to this, when I was curating the group show, Dustsceawung, and organizing my concurrent solo exhibition, TEOTWAWKI, for DEMO Project in 2016, I saw that not only did the community want a thoughtful and contemporary dialog, but that traveling an hour and a half for two exhibitions was not a problem.

In central Illinois, artists, curators, teachers, and art administrators understand the need for structural support from each other in order for the community to work. Through this structure, the perceived weakness of social and geographic distance becomes a call to action that keeps the community strong. Stretching forward, the Springfield and central Illinois auxetic art community will inevitably change and contend with issues of growth, resources, visibility, and inclusion of historically underrepresented artists and narratives. The artists and institutions in the region will be called again to act and they will expand laterally to meet the task.

Feature image: Installation view of Dustsceawung, 2016, curated by Adam Farcus. Artwork by Harold Mendez, Stephen Hendee, and Erin Washington. Photograph by Brytton Bjorngaard.

Sources:

Auxetic Materials. Alderson, A & Alderson, KL. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part G: Journal of Aerospace Engineering, Volume 221. 2007.

Coincident molecular auxeticity and negative order parameter in a liquid crystal elastomer. Mistry, D, et. al. Nature Communications. 2018.

Adam Farcus is a Lubbock, Texas, based activist, artist, curator, feminist, and teacher. They were born and raised in the rural town of Coal City, Illinois. Adam received their M.F.A. from the University of Illinois at Chicago, B.F.A. from Illinois State University, and A.A. from Joliet Junior College. Their work has been exhibited at numerous venues, including The Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth; Vox Populi, Philadelphia; the American University Museum; and Advance Art Museum, Changsha, China. From 2012 through 2015 they were also a co-curator, with Allison Yasukawa, for the Baltimore-based residential art space, Lease Agreement. Lease Agreement now exists as an alternative curatorial project, based in Lubbock, Texas. Adam is a professor of art at Texas Tech University.