On August 7th of this year, Milwaukee’s Bronzeville Center of the Arts debuted “Black Defined 1: Ceramics,” curated by Phoenix Brown, which is the first part of their Black Defined series. Its title suggests the exhibition begins answering a complicated question—how is Blackness defined, beyond race and ancestry?

The exhibition addresses how Black artists during the colonial era and in the present define themselves in the face of enslavement, displacement, and cultural appropriation, using the medium of ceramics as a ground for exploration and storytelling. This exhibition does not shy away from showing how Black people have experienced great loss—of personal history, of family, and more that cannot be measured—because of colonialism and white supremacy. However, in the gathering of clay, stone, porcelain, Black art, culture, and traditions will thrive as long as Black people continue to live and create. Though Black people have experienced immense harm and devastation because of slavery and systemic oppression, “Black Defined 1: Ceramics” promises us that we will always have the power to define our experiences on our own terms.

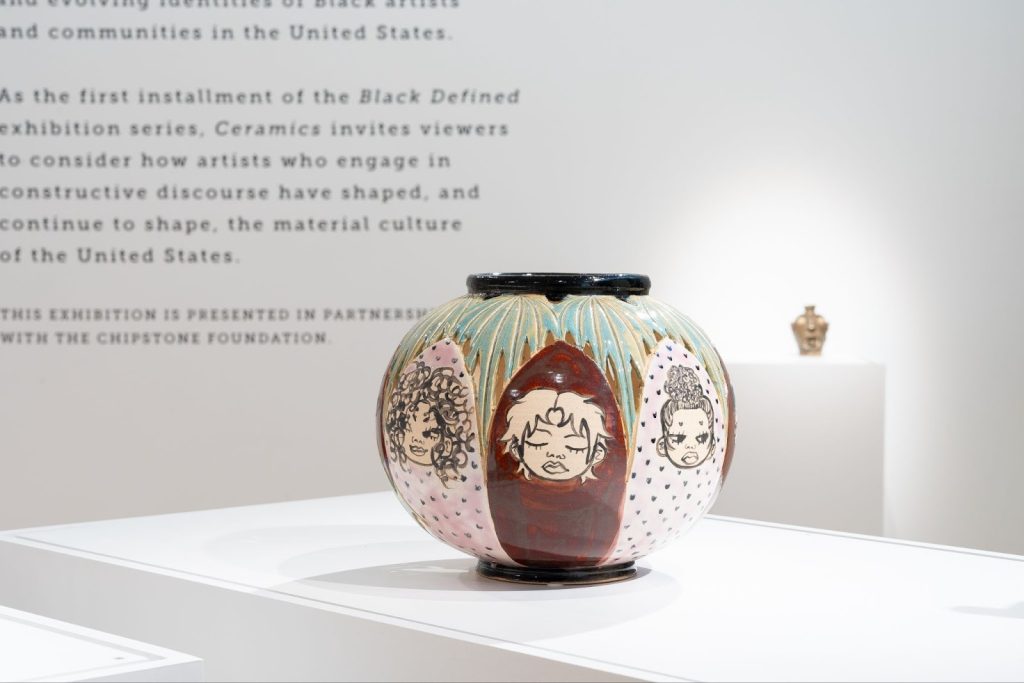

At first glance, these ceramics—rugged and chipped earthenware bowls, a tall vase adorned by pearls, a dish branded with graffiti—look connected only by their shared medium. Upon closer inspection, they span generations, speak to each other, and echo similar forms and techniques that vary and evolve. For example, I sensed a link between the alkaline-glazed 19th-century face jug and Sydnie Jimenez’s Double Spouted Hoodie Vessel, made of glazed terracotta. The older jug wears a haunted expression with white kaolin eyes bulging out of its head, while Jimenez’s vessel remains at rest as it keeps its long-lashed eyes closed. Both stand out as having the connection of a face, which is often the primary way we identify another person. The face on Jimenez’s piece is more human-like than the alkaline jug, which is warped as if to intentionally obscure the face’s true identity and ward off onlookers from what the vessel may contain.

Seeing Jimenez’s piece alongside the alkaline-glazed stoneware vessel reveals a perceptible evolution of the lineage of the African American face jug. Early forms of the face jug can be traced back to Central and West Africa, where people made face jugs to contain intangible components, such as spirits and ethereal medicine. The tradition was brought to the United States by enslaved African people and could be spotted throughout the American South in the mid-1800s, but was most notably created by enslaved potters who worked in the Edgefield District of South Carolina. The white kaolin used to detail the eyes and teeth is similar to how African people would use kaolin to mark their faces to denote the presence of a spirit or god inhabiting that person. Though Jiminez’s vessel forgoes the use of kaolin, the two spouts that jut from the resting face are reminiscent of devil horns. These two spouts perhaps denote a spiritual, yet rebellious spirit within herself, which contributes to how Black people across the African diaspora have defined their relationship to the spiritual world.

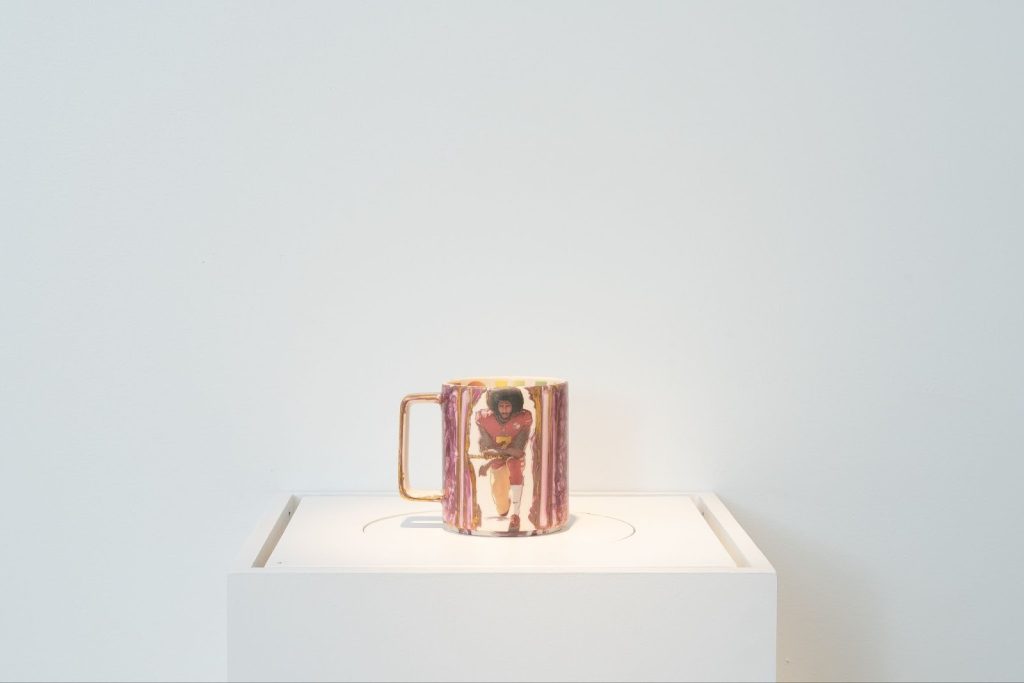

Moving towards the furthest corner, there is a similar connection between David Drake’s alkaline-glazed storage jar and Michelle Erickson’s Remember. Both vessels were originally made to hold liquid; Drake, commonly known as Dave the Potter, crafted a jar that holds up to three gallons, as seen by the three perforations near the jar’s opening, while Erickson’s mug could hold a cup of coffee. While different sizes, these pieces have a shared original purpose; they were commercial products to be sold for profit. It is not known if Dave was initially taught to read by his first enslaver, Abner Landrum, or if Dave learned how on his own. However, Dave was given away by Landrum to be enslaved by his son-in-law, Lewis Miles (whose initials can also be seen on Dave’s jar), and would go on to make jars for Miles’ pottery business for the next two decades. With Erickson’s piece, you can faintly see a Starbucks logo peeking through a layer of gold paint. Starbucks has also been heavily criticized for utilizing slave labor practices. This was exposed in 2018 when Brazilian labor inspectors tied Starbucks to plantations where laborers were forced to work in dire, filthy working conditions while their pay was stolen from them.

With the addition of Drake’s signature in grand, cursive letters across the jar’s surface and Erickson’s two portraits on opposing sides of the cup—the first being of football player and activist Colin Kaepernick and the other a kneeling Black woman—the artists turns these ceramics from products made to profit from the backs of Black labor to art that resoundingly condemns these exploitative practices. More than this, Dave and Erickson reclaim these objects by transforming these commodities into art that represents resistance in the face of systemic oppression, art that affirms the humanity of Black people above all else, and art that redefines events of exploitation wholly from their own perspective.

In addition to showing the evolution of African American art, this exhibition also gives insight into how Black people used ceramics throughout time to support everyday routines. A collection of colonoware, two bowls, and a kettle, lines one wall of the gallery that were used by enslaved people during the late 1700s and early 1800s. The colonoware on display was discovered in South Carolina’s Cooper River, which flowed in a region home to a large population of Gullah Geechee descendants. These ceramics were not considered art then. They were daily objects made by enslaved people to hold food and water that helped feed, nourish, and sustain themselves without having to depend on European-made ceramics that were often inadequate or hard to obtain. Moving forward in time, we see a larger bowl than earthenware dishes. This one is adorned with graffiti (Robert Lugo’s 40 Cooler 4), a style of art that typically would be seen on the sides of buildings and concrete walls. The graffiti documents the names of his community as an homage to them. with each tag marking the influence a friend, mentor, or family member has had on his own art. Lugo takes his inspiration from Italian wine coolers, typically made to be used by wealthy families, and instead makes something that could be used to support the everyday needs of a modern Black home.

Additionally, on display in the gallery are a series of vases, one of which is made of glazed white porcelain and is embellished with dangling pearls and twirling ceramic pink ribbon (Alisa Drakes’ Pretty in Pink; A Perfunctory Femininity), another porcelain vase is an earthy brown with knotted porcelain ropes restraining its body (Alisa Drakes’ Sub Space). These ceramics, made by contemporary artists, are not made to be used; they are made to be seen, recorded, and serve as the artists’ self-portraits, defined by their lived experiences, represented by the shaping of these vessels into their final forms by their own hand. Drake’s vases also stand in as a representation of core parts of their identity as well as highlight personal sites of conflicts relating to their sense of self—for example, a pressure to perform femininity as perfectly as the pearls and bows precariously placed on Drake’s vase.

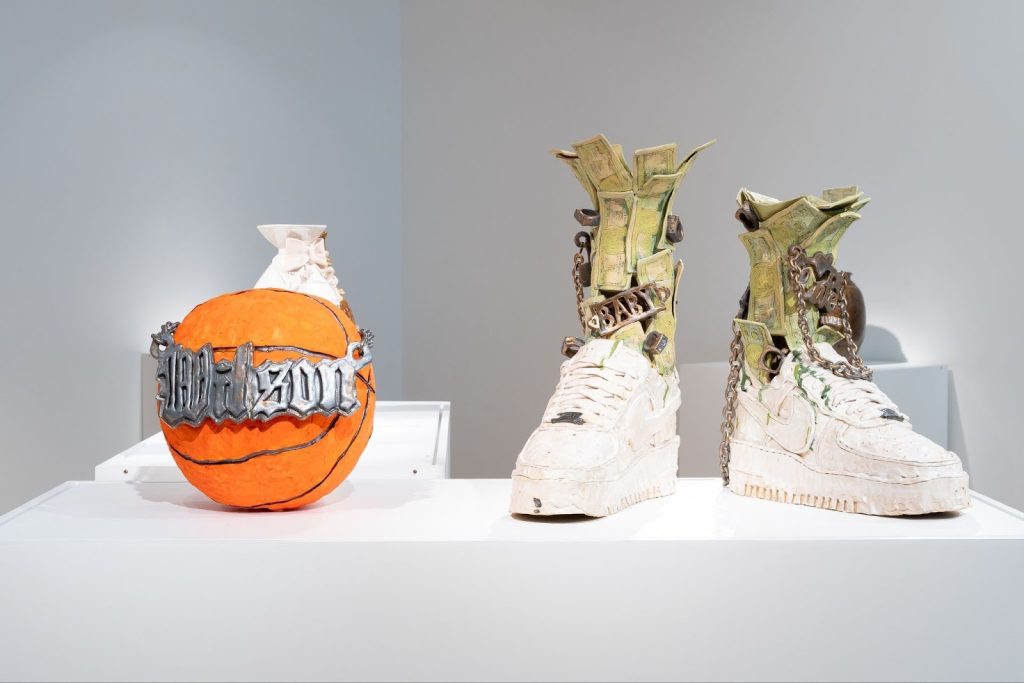

Black Defined 1: Ceramics culminates in two striking glazed stoneware pieces positioned in the gallery’s center. One of them is an enormous basketball wrapped in a chrome chain with a “Wilson” nameplate (Janiece Maddox’s Wilson’s ), and the other is a pair of oversized white Air Force 1 sneakers partially made of crinkled dollar bills (Janiece Maddox’s Ca$h AF1 ). And, like the basketball, each shoe also wears a chrome chain. Both ceramics are super-sized replicas of iconic cultural symbols that Black American athletes and youth have worn with pride for decades. However, the dollar bills, crinkled and dull, and the weighty chains, which look more restrictive than the typical chains worn for fashion, are a stark reminder of how these objects have been sold to Black consumers on the basis that these are the defining images of Black American culture, when in reality, these objects cannot be removed from the businesses who manufacture them by appropriating aspects of Black culture to gain maximum profit. Maddox specifically references the Nike brand in this work, which has been critiqued for co-opting social justice movements and commodifying them.

Black Defined 1: Ceramics marks the beginning of a larger series, because the process of determining what defines Blackness—as a culture and as an identity—will always be ongoing. Though perhaps this process of self-definition may never feel complete, what this exhibition proves is it is essential for Black people to continue telling our own stories, especially in the face of attempts to have our narratives defined for us through the sanitization of Black history. Furthermore, seeing these works from different times all in the same room, it is also apparent that while white people have relentlessly tried to benefit from Black labor and appropriate Black culture, they can never take ownership over what lives within us. Black culture and traditions are embodied knowledge—embedded in hands that mold clay and in the creativity that continues to reimagine what has come before. The exhibition rejects the narrative of “recovering what is lost” and instead reminds us that nothing has been lost but embodied.

About the Author: Nadya Kelly (she/her) is an arts writer based in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. She uses text and audio to explore themes of Blackness, imagination, girlhood, through the lens of visual art, music, and performance and has written for publications across the Midwest, including Newcity Art and Milwaukee’s NPR. Nadya holds an MA in Arts Journalism from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and currently writes personal and cultural essays for her online blog arbitraryminus.