***a writer’s note: in lieu of recent egregious acts made by the Poetry Foundation, it is strikingly apparent that there is no safety in neutrality. Re-centering the faith in the power of the written word, acts of silencing are perpetual acts of violence. We are all experiencing such profound suffering and loss and artists help us to articulate the transformation required to not only imagine but enact change from the rubble of collapsing systems. This note makes for a small, but wishfully profound, ripple of solidarity with artists working under capitalism, peoples fighting occupations in every corner of the world, and many others living through and dying from genocide in Sudan, Congo, Haiti, Palestine, and so many other unnamed places.

When I find myself searching for faith, I always find my footing in music. As of late, I return almost daily to the interlude “We Go Through Changes” by The Emotions as a black optimistic register, a register that carries a mythical and ecological reassurance that everything is every thing when my other senses seem panic stricken and overworked. Sonic temporalities communicate in a dialect that helps me to reattach my cognition to my constitution—I feel possible after hearing the hypnotic psalm “We go through changes, changes we go through”. This melodic anchor and others reanimate my daily interior life reminding me that new guidance systems can take shape from the ruins of this world. As I press repeat again and again on my Frustula playlist, I wonder what composes the soundtrack of these times for others? What apotropaic sounds furnish the revolution? What sounds announce its arrival?

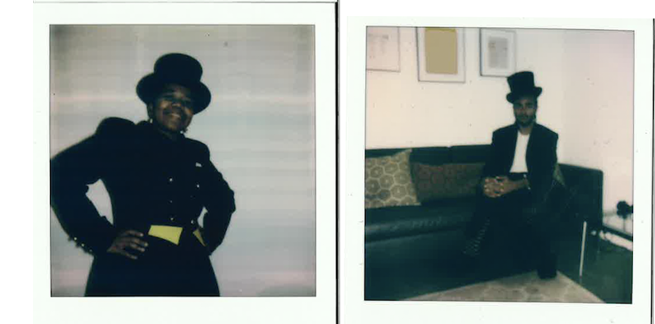

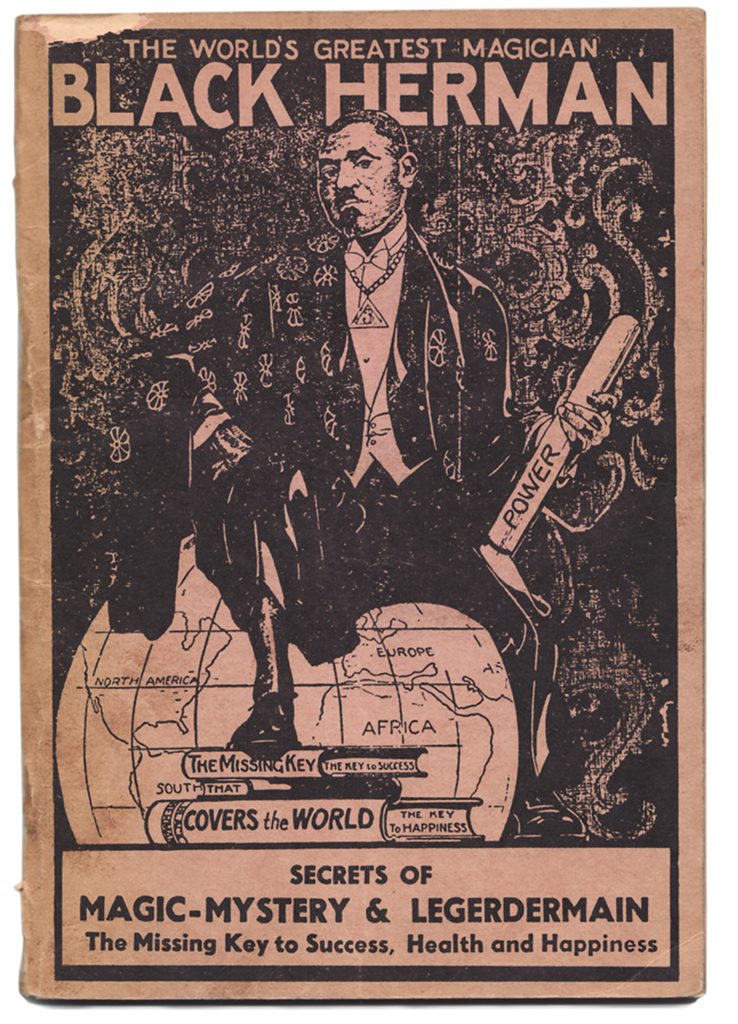

Nestled in the fantastical legacy of the Black Herman, the most prominent African American magician of his time, and the boundless love between jazz and poetry, Herman’s Lounge: A Night of Prose and Rhyme offered a panoply of sonic sensibilities. Jared, Janelle and I spoke several weeks after the balmy evening of events. The spaciousness between the performance and our chat allowed us to decompress, process, and return—still struck by the magnitude of the experience we shared.

isra rene: Herman’s Lounge made for such a dynamic container space. It seemed that illusion, sonic choreographies, and jazz influenced oration were actively disassembled and reassembled. Why Herman’s Lounge now?

Jared Brown: Well, it is all grounded under the umbrella of Jazz as a Communication, a class that Gabrielle Octavia Rucker led in the fall of 2022. And even prior to us being admitted into the class, the prompt of “how do you define jazz?” in the application process helped Janelle and I to begin to define what jazz is for ourselves. I distinctly remember Brianna Perry, who was also in that class, mentioning Black Herman in response to a poem that I wrote. I thought it was cool that Gabrielle gave everyone space to define what jazz was, and my definition was just simply: jazz is disobedient.

Janelle Miller: I think jazz has been transmuted. Jazz has now become an art form that feels like it encapsulates a lot of people having access to that space when jazz was found typically in a black space of conversation. I feel like it is a Black American musical practice and tradition, and it’s Black people talking to each other through sonic sounds. To me, Herman’s Lounge encapsulates that honoring and tradition of being in dialogue of transmuting and creating magic from the tools and sources that have already existed.

IR: The opening performance was so visceral. I think the eulogy is such a votive practice of commemoration, especially because eulogies aren’t known to be heard by the person they’re about. It was so compelling that the opening scene collapsed itself as the introduction to the show but also as a vignette of a funeral. When you both asked “Does anyone have any words about the deceased?” I thought, ‘WOW, anything could stand in for “the deceased”.’

JM: There is a musician, Art Blakey, who said this phrasing during an actual eulogy. We rephrased it for our piece, but it’s basically holding that space, allowing us to be the vessels for that evening. Though Herman is the pillar for the evening, with our research for this show it welcomed in a whole cast of figures. We were talking a lot about Lil Hardin Armstrong, Baby Dodds, Johnny Dodds, Charles C. Dawson, and Jelly Roll Morton. So though those figures weren’t explicitly mentioned or the sites of the old theaters and spaces that they performed in, they were present in the room. We were experiencing a lot of death within the Chicago community at that time, particularly black people like Roderick Sawyer and Don Crescendo. We wanted to allow people in the audience to reflect, and have that site and source to welcome whoever they wanted into the performance.

JB: And although nobody may have spoken up at that moment, I think that just giving people the potential space that they may need or not need was still an ode to a sort of generosity that happens when you grieve collectively. I was definitely very impacted by grief at that time with Don specifically. KeiyaA supplemented it in a line where she said “real niggas never die”. And after hearing that I felt like, okay, I can heal a little bit of something. Things that we said that night helped me to mourn in real time.

IR: Each artist seemed to have their own rendition, or reperformance, to the question of “Does anyone have any words about the deceased?” And having the backdrop of the lounge accentuated my understanding that mourning can happen anywhere, it isn’t specific to the spatial politics of a church or cathedral. It can happen at the club, on the corner, or in the transformed space of the Poetry Foundation; there was a revision of the architectural vernacular of the space. People were able to move differently because of the curatorial reformation from “Foundation” to lounge.

JB: I want to highlight how Noa’s [co-curator of Herman’s Lounge and Public Programs Curator at Poetry Foundation] curatorial presence existed in Poetry [Foundation], even prior to Herman’s Lounge which really guided the structural reformation for the night. I think that she’s someone that wants to always complicate or obscure the traditional, transactional thing between performer and audience. And Janelle and I were really adamant about going to the nth degree of how to disrupt that too. A lot of that did have to do with orienting the space so that it wasn’t a sterile, typical orientation for people who have been there before. We found out later that night that a lot of people had never been there before—a lot of Chicagoans. That, in of itself, is a wild concept to think that native Chicago people, who have spent X amount of years in Chicago, had never been to the Poetry Foundation. So I think Noa was also just really good at accommodating that ongoing conversation around accessibility. We worked closely with her and other staff members like Maya and Orlando, tech specialists at Poetry [Foundation], who really helped create an ethos for that night that felt authentic but also disruptive of what Poetry [Foundation] typically does. We wanted to distinguish this as a lounge and the domain space of a lounge feels like a space where there is an organic rift between audience and performer or those things can be interchangeable. I wanted it to feel like anybody could walk up and be a part of the ensemble. Also, Janelle and I were cognizant of the financial stipulation of putting together this event. We wanted this to be free and for artists to be paid reasonably and compensated for transportation and food. These things should not disrupt accessibility for the general public. It shouldn’t be compromised. I don’t think that it should cost more money to experience music and culture in a city that generates so much culture.

JM: And to add to your point, the Poetry Foundation does an exemplary job with interpretation, and that is not something that we always get a chance to experience. It really welcomes a wider audience that can be present. I’m thankful to the interpreters from that evening. They really added a layer of dynamism to the work. When Jared and I were thinking about spaces to have Herman’s Lounge, this was a main reason we chose Poetry [Foundation]. I hope more sites across the city make ASL interpretation a priority in the future.

IR: All of these components and considerations build together to create a space that reaches a landscape of sensibilities. I am reminded of a moment after the event where a friend described the night as “balmy” and I thought that was such an appropriate word for the evening. Balmy meaning pleasantly warm while a more antiquated definition of the word is rooted in “crazy or insane”. There were so many times throughout the night where the emotive barometer reached drastic octaves that sometimes nightlife today doesn’t reach.

JB: We still had to contend with the physical limitations of what the space could and would not do for safety reasons. If it were up to me, we’d be smoking cigarettes and weed and we would have some Narcan in case the girls wanted to invoke other spirits. You know what I mean? I want the girls to come in authentic. And sometimes that might mean the girls are high and I want all of that. I want all that negotiation because that is the real ethos of the space. People in the city take public transportation and get tried in all these different ways. And I think musical spaces are a place where people can unfasten that or to leave something there. Or even church—they’re not that different.

IR: I’m glad you bring up church as a backdrop for spaces that “invoke.” Can you speak to the duality and relationship between Black spirituality and death in this event?

JB: A precedent that was inadvertently set for me at a young age has a lot to do with going to church. I think the ethos of church is like no matter what you endure in this material physical world, in death you will be free. And then there comes a time when you get older and you start pushing back against that. I think my angst really wrapped something up in me where if you’re like, okay, and that may be true, and I also want to be free right now, and I don’t want to apologize for that. And I think actually jazz is an entryway, feels like a really appropriate entryway. I think that disobedience is the offset of that. I want to live now. I want to make music that doesn’t adhere to whatever legible music structure that was before this. I just want to be in the now and live in the now and be free right now. I don’t want to have to die in order to be free. And I think with everything going on now in the world I keep hearing this part in KeiyaA’s set because when I heard “ real niggas neva die,” it […] make me think about how you can’t control, how things permeate, and even if somebody is physically not here, you can’t undo the impact. The more you just take up space, that just keeps going. Anybody that saw the look, anybody that heard the scream, anybody that got cursed out by you, read by you or whatever, you do not die. It still keeps going and changes. I’m thinking about how we all saw All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt. This film is thinking through the notion that water just changes and things just change. That’s kind of how I’ve been meditating on it. I mean, real niggas neva die. And if you’re saying real shit, that’s never going to die.

IR: There is an article online titled “Black Herman Comes Through Every Seven Years” alluding to a long standing and contested trick where he faked his own death, but would dramatically come back to life. He was an illusionist and has a long legacy that supersedes him in the most interesting and perplexing ways. For instance, in the midst of my research of Black Herman I stumbled upon Herman Roberts Show Lounge, a prominent jazz lounge owned and operated by Herman Robert on the Southside of Chicago from 1954 to 1961. I am convinced that this is a spiritual ripple of Black Herman—life and death live on the same line.

JM: One thing I will say is as soon as you enter this life, you’re ushered into this form and then you have to be confronted and greeted by death as an ever-looming presence. Everything that you do impacts and has ripples around you. So, going back to water, I think about how it is said that water doesn’t forget for hundreds and hundreds of years—the impact and ripples are felt through. I think about every ripple that my ancestors made that impacts how I feel, my health, how I think about things, and how all those things are imprinted upon me. I think the special thing about Herman’s Lounge, even though we were talking about Black Herman, we wanted to honor how amazing it was to have musicians from the South, who came to Chicago at the turn of the century, and left a big impact that we have to go back and reflect upon their legacy. That’s meaningful! You may have wiped away the Pekin Theater, you may have wiped away the physical buildings that were standing in on these sites and everyone who we’re talking about is no longer here, but their impact, sonically and spiritually, is still here with us.

IR: There are resonants that sometimes don’t really settle until days or even weeks after performances. I am still thinking about the moments when Ben Lamar Gay meandered throughout the space taping his sticks on the floor—something reset in me every time he did that… I still hear the bird call of Dee Alexander and still feel KeiyaA’s guttural wail in my bones.

JB: That makes me think about comprehension and people trying to give proof that they understood something. Some feedback that I got from people in attendance were like, ‘well, there were moments where I didn’t understand this’ and some clarification was given, but a lot of it wasn’t. It made me begin to think about how Black artists and musicians are at the mercy of genre. I think that there were some people in attendance that maybe had a starkly different definition of jazz than the collective definition that Janelle, me, KeiyaA, Gabrielle, Ben, and Dee created together just by being in space together. Their feedback served as a riff. Being in the audience doesn’t mean that you have to be passive or not accounted for.

IR: “At the mercy of genre” is so poignant. I spoke with Noa and she described collaborative projects between genres, like Herman’s Lounge, as a way to “complicate language as a form of relation”. Understanding the slipperiness between genres, in this context, as relational rather than illegible is so informative. New definitions and glossaries take shape…

JB: At Herman’s Lounge, we saw the etymology of blues to jazz to gospel…

JM: And they want to separate it so bad. When you look at early music, Black music history, all things were in direct conversation informing each other. One thing about early music research is a lot of blues women were the foundation to recording industry music which set the stage for jazz. In particular, when I was hearing KeiyaA that evening, I was thinking about the history of that early recorded music.

JB: I feel like her stuff really bent time in a way because it was still very electronic, but also soulful and bluesy. That’s why I love KeiyaA’s music and her output so much because I think that it is a prompt for us all as Black people right now to really unpack what genre is and isn’t doing for us anymore. I’ve seen iterations of her performance where it’s felt more punk. I’ve seen times where it has had this quintessential soul R&B feel, and I’ve seen it at other times where it’s a hybrid of all those things. Or even thinking about Gabrielle at the typewriter and those sounds coming through.

IR: Very Lorraine Hansberry, Gwendolyn Brooks…

JB: I mean, yes, Gabrielle tore it. This lineup was the original lineup that Janelle and I were talking about almost a year ago. We had never really gone to these levels of trying to make something in this space, but that lineup was the original lineup. That’s how I knew it was blessed.

IR: It seems that nestling into a genre is becoming more and more straining and obsolete for Black artists. How do you both think of jazz as an umbrella for new and evolving forms of communication in Black sonics?

JB: I’m not sure that jazz ought to be an umbrella for newer and evolving Black musical and sonic practices, however I do hope that budding musicians invoke the experimental and disobedient disposition that many of our jazz ancestors embodied. And by embodying that disobedience, may it open expansive doors that allow black musicians and sound artists to disavow themselves from the rigid often myopic limitations of genre… perhaps we are on the brink of a newer genre. And if so, may it be as Black as ever and ours as ever, forever until it’s time to evolve again.

JM: And to that I say Amen, Asé, and all spirited things!

About the author: isra rene is a curator of care weaving webs of dreams tufted by our inherent connections of love, vulnerability, and care.