I was able to schedule an appointment to see Wash & Set at Hawthorn Contemporary on a sunny Tuesday morning. Entering the large, white-walled gallery was disorienting at first, as I haven’t been inside an art space since last March. Being isolated in a space designed for conversation felt chilly and brought attention to my body. Fortunately, I was in this hollow space with a collection of intimate works by LaNia Sproles and Ariana Vaeth. The uniformly desktop scale of the works exhibited invited me into vignettes of their lives. As I made my way through the gallery, I felt my shoulders relax and my attention moved from myself to scenes of celebration, leisure, and love.

I met Sproles and Vaeth while studying at the Milwaukee Institute of Art & Design. Before this, Sproles was a student at High School of the Arts in Milwaukee, a school that allows students two hours per day to focus on art and hone their skills. Being that it had a more diverse student body than her previous school in the suburbs, she developed an understanding of the ways in which young POC are treated differently than white students. Sproles described this difference as “The environment in Black and brown schools are run like mini prison complexes. Going to school was where [students] ate for that day, so it made me realize that it is very hard to be Black.” Meanwhile, Vaeth, having grown up in Baltimore, attended the Carver Center for Art & Technology, which functions as a magnet school in Baltimore’s suburbs and also has an arts-focused curriculum. In our conversation she explained to me that “It had [a] community because not just the students wanted to be there, also that the parents could [afford to] take their children to that school. In my class, there was a strong collection of Black women and that shit has embedded itself in me to this day.”

The works in Wash & Set are a welcome re-frame of the past year, focusing on intimate relations with loved ones and oneself through environmental portraiture and dreamscapes. In doing so, they center a proclamation of pleasure without giving a white viewer the catharsis of a neatly contextualized oppression. 2020 saw an explosion of aestheticized infographics and informative, if brief, social media posts simplifying the very complex issues of racism in America. While I don’t doubt this form of ‘activism’ helped to radicalize some white liberals, very little can be said about its merits to affect change. The proliferation of appearing engaged has extended to the art world as well. The sudden shift in programming from major galleries and museums to promote artists of color has further brought into question how these institutions have disparaged Black and brown artists and to what degree the opportunities now presented to such artists provide value. Wash & Set is an exhibition by two Black femmes focusing on who they are and their capacity for joy and pleasure rather than their struggle. With many Americans seriously engaging with racial discourse for the first time in the aftermath of last summer’s protests, there has been little room for nuance, especially when BIPOC are called on to educate their white peers. Sproles’ and Vaeth’s works push against the notion that depictions of Black people in art is inherently political, opting for an actualization of self through pleasure, stillness, and love.

In the exhibition statement, Sproles and Vaeth state: “In the fading utilized acts of self-care, these best friends depict in their works what it looks like to pour back into their lives when given the bare bones. Their work stems from the impossibility of commemorating the ones that shape them. Wash & Set is merely preparation to fall into our softest tresses of ourselves, something much sweeter than perfecting survival.” It is through this depiction that I was able to breathe and understand the very human need to recognize myself; to recognize my body inside the white-walled gallery and the capacity I have to love my familiars and myself.

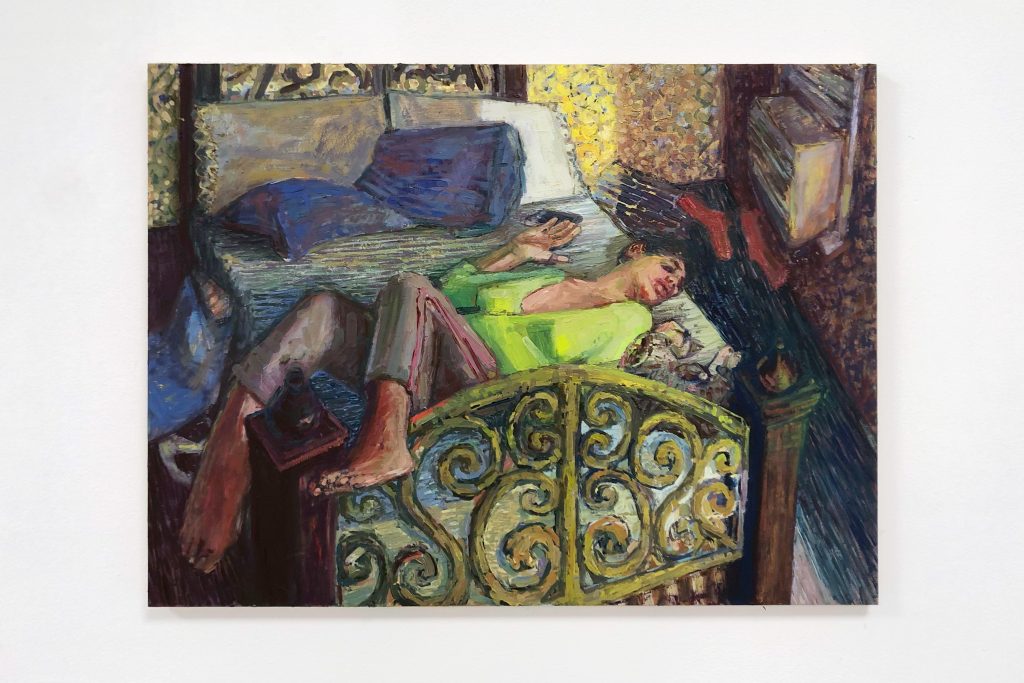

Vaeth’s paintings exist in a self-referential continuum, functioning as snapshots in a photo album or episodes in a series. Through their small scale and vibrant, warm light, scenes of repairing a leaky pipe (L’il Handy) or taking a bath (Zombie Encounter) are filled with love and reverence. She finds herself at her mother’s home in Mt. Olive, NC, through empathetic displays of stillness and family. Vaeth’s work has been an ongoing love letter to those she holds close to her heart, focusing on the intimacy shared in private such as dying hair with friends or cuddling in bed. All of the pieces made for Wash & Set come from her time with her mother, and earnestly speak to the need of retreating into togetherness and self-love.

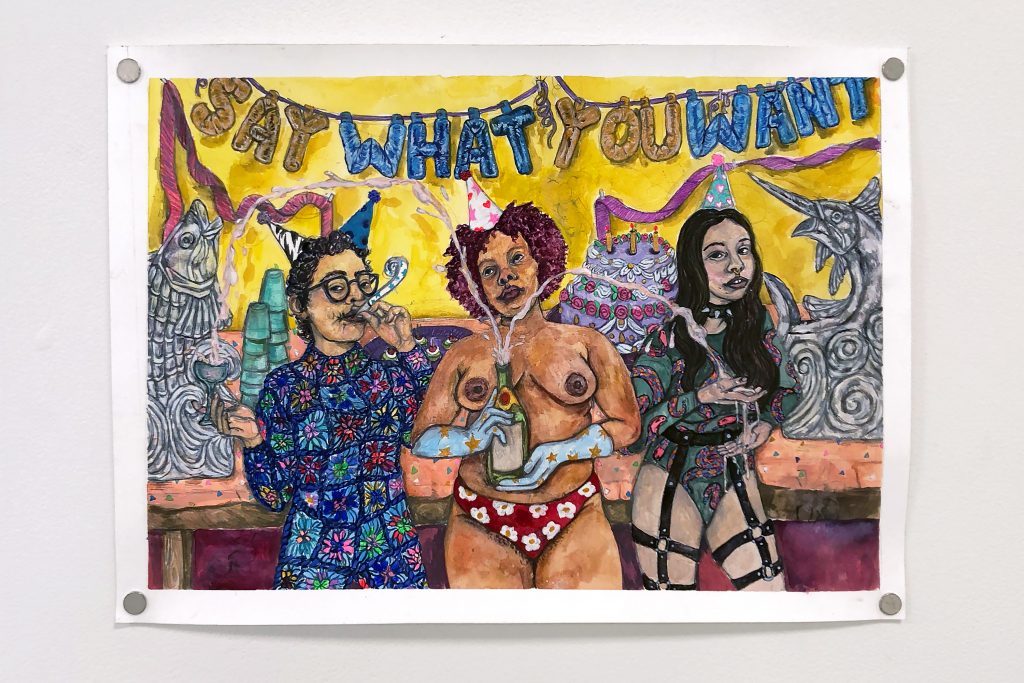

Sproles’ drawings and collages depict a romanticized togetherness, occasionally occupying spaces that have often become associated with a negative self-image ─ making jokes while staring in a bathroom sink (Major Loser), or creating ritualistic love in an alley by a dumpster (Superstar). By reframing these scenes, Sproles creates a marble fountain in a kiddie pool (Swan Lake) and a sacrament in a house party (A Thotquarian Ball). She is deeply empathetic to the queer, femme, and Black subjects in her work, portraying the way they see themselves rather than what they are.

Joe Acri: The lived environment, and the day-to-day surroundings that you experience in life being in Milwaukee, being in Baltimore, commuting, going to schools; to what extent has that influenced your art practice for both of you and the kind of themes and subject matter that you focus on?

LaNia Sproles: I would say it is. Going to MIAD and developing all of these relationships with the people that I still have relationships with today, I am extremely appreciative. They come back in my work, and just like the people I have relied on in the past couple of years, my work has become more documenting what is happening around me and these relationships and my own turmoil. Documenting the things that I’m going through also means documenting the things that I am dealing with outside of these relationships as well. My commute to MIAD was 40 minutes there, 40 minutes back, and I lived in a Black neighborhood and I would go to my really white school. I was used to going in between these two different spaces and having two different ways of communicating and traveling. That was just the result of living at home while I attended college. So, all of that is making sure I am documenting everything that is happening to me, whether good or bad.

Ariana Vaeth: Art School put a lot of like-minded people together. I feel very much that the work that I make, and the work that we both make, follows not just the bonds that we made, but the complex feelings of joy and sadness and melancholy; especially following school when you don’t have those people immediately next to you. For my ideas, there is some kind of want for me to be reflecting where I am at certain moments. I’m always thinking about people that I have relationships with. I just have to really be secure with the subject matter. I am thinking about the show and I specifically wanted to make work when I wanted to go to my mom’s house. I just wanted to get there and get into the hearth. Being able to start there, it did kind of prove to me how important it was. There were so many ideas I had drawn before I got there and that wasn’t what it was about, it never could have been what it was about. But I had to try to get my brain moving in the process of the practice, even though I knew that the process would be futile.

JA: You have both worked kind of alongside and with one another for a while now. Appearing in each other’s works, collaborating with similar people. Is that a product of both of your time spent at MIAD developing those relationships further and having a mutually beneficial artistic voice? I’m also just curious about the effect of the necessity of a code-switch that existed in going to MIAD, and the effect that that has had with the relationships that were made there, and going forward.

LS: I mean, if it is a white dominated space, all of the Black people look at each other and sort of connect because it’s strength in numbers, or it is more like a mutual understanding of each other. I almost feel that was just sort of inherent and if I think about all of the friends that I made, they’re mainly people of color. You find comfort in familiar company. Obviously, because I went to MIAD, I got to meet some of the most important people in my life. I would say that I have met some people outside of that institution as well. When Tianna Buie left Milwaukee, I still stayed in contact with her and she is still a good mentor of mine. We have a mutual respect and understanding and love for each other. Maintaining those relationships with these people kind of helped me realize that I am not alone, that we are all struggling, and we are all trying to move elbows around to make room for ourselves. Especially the close friends that I made at MIAD, mainly because they are all non-binary, femme, or BIPOC folks. That just happens naturally. Not because we feel like we have to, but because it is just the right thing to do.

AV: I think you are drawn together through these kinds of cultural phenomenons. As I got to thinking about school, each person you touch base with knows another person, and that is how the camaraderie really gets forged. I think about my life trajectory and what I can accomplish, but also having concrete aspirations isn’t actually that helpful. I think they are very clout-based.

JA: I was wondering if you both could speak on the way in which your presentation through the artwork, within the stage scenarios, or collaged bodies, and imagined spaces have been used by each of you to speak to a cathartic ideation of place; or the compassion that you both were talking about.

LS: I feel like that is always going to be a struggle–struggling for autonomy and place and power in general. It is a power struggle and to put all of the things that we have to deal with being femme, Black, or for me being queer, are always going to be a part of our struggle. But being able to see that in other people is the most important part of being empathetic. Making work about people that we care about is not only seeing them for what they are, but seeing them as the human they are, as opposed to a shared struggle, or a shared common knowledge of melancholy that we all will experience during adulthood. Even the clothes they wear influences a lot of my decision-making and thinking about what sort of bodies are put on a pedestal. I am thinking about all of that, and thinking about their personalities, and how that can translate through clothing, how that has become sort of a freedom or a way of expressing how you feel and how important it is.

I am also looking at the way people curate themselves on Instagram, specifically Black queer people, and I get a lot of my inspiration from the things that I see on social media, on Black Twitter, or even memes. Not every space is meant to be inhabited by white people, and I think the more I draw from those inspirations, I can further talk about these relationships with these people. It makes me feel good that at least I know that I am paying attention and nurturing a lot of these relationships that I do have with these people. The fact that they know I would go out of my way to make sure that they are seen in a certain way that makes them feel uplifted and in a pleasurable state.

AV: It’s affirming when I see the work of LaNia’s in the show about how often people want to express themselves. If they truly had the resources to express themselves the way they wanted to, or they felt safe enough to be portrayed in the way the people see themselves in your work, I think their reaction is shock, but in this very playful, sometimes inviting way that they didn’t think of. I am still trying to decolonize the way I think about my art-making. And how much of that worth comes from rules that I didn’t make, and how important it is for me to make the rules in the work. If I didn’t start, there was never going to be a time where I am fully secure in it. That’s kind of how I was thinking of things, because of a particular esteem I hold LaNia in. That is also the very unique challenge of the show; that is a challenge that I will look back on as I continue to work towards the solution. It was good because the challenge was very internal, and that is what I like about that situation. It was all about what is in my head, which sounds dangerous, but I actually do want to figure it out.

LS: I think you are!

AV: I think I am. As I keep making more it will continue to be.

LS: Like I said, it is important to capture these really tender moments that you aren’t always invited to. I think in a lot of people’s work it is really important to talk about moments unseen. Even being your close friend Ariana, I don’t really know what it is like to be at your mom’s house. But I feel like I understand it by looking at your paintings. Often a lot of what is authentic and what is authentic to Blackness, is being questioned. Who gets to own it and who gets to commodify it is always in question. That authenticity is always being questioned, so I think it is very important that we talk about that.

JA: It appears that the two of you have found a real grounding and real traction in your art careers. A through line that I have noticed in both of your emerging art careers is this reverent utilization of your familial relationships, through blood or otherwise. Ariana, could you talk more about how your mini-residency at your mom’s house in Mount Olive, the self removal from social media, and those power structures that exist, had an effect on the work that you made for this show?

AV: When I think about it, I always have a home. Not everybody has that. So, it’s in my head that I know that I will be dedicated but I always know that I can do another several months stay over there and remove myself from odd things and that is going to be a way for me to organize myself. It wasn’t spoken about in the work, but when I think about exhibitions in the future, and when I think about extended family as I get to know them more — we already had a very sparse relationship — but it is making me know where my touch points, any place that I have where I can have an extended stay, are. While it took a long time for me to build them in Milwaukee and it seems very hard for me to build them in other places, having a place to be makes it a lot easier to even start. I’m taking things into my own hands, like the residency. Thinking about things I want, and how I can just make them, and that is actually how you get them. You have to prove yourself disciplined.

LS: We have created a lot of the joy in our lives, and that is hard work. Again, things in the art world are very futile, unpredictable, so a lot of that stuff you have to just make your own room for. It’s nice, I think, having to be self-reliant that much. But like I said, you have to make time to create the things that you want to see come to fruition.

AV: I like that! I know we are having all of these internal conversations, but it is so hard sometimes.

[laughter]

JA: LaNia, so much of your recent work has been drawn from a reckoning of queer femme Black visibility. I’m curious about the relationship with loved ones and the self presented in your work; how does all of that come together and merge into a cohesive thing?

LS: I think now I’m starting to diversify not only what I perceive to be femme, but how the world perceives femme. It is a lot more broad; having a queer non-binary sibling helps me put those things into perspective. Not necessarily that they are aiding me, but there is something to be said when you grow up in the same home and experience similar treatment to different degrees. I see myself in a lot of these people and in the way I walk through the world, if that makes sense. Part of my process is being able to find common ground with those people and making sure that they are seen. I am also finding common connections in the things that they deal with as Black femmes.

There is this special resilience. I get strength from a lot of Black femmes in my life. Being able to get your shit together and being strong enough to hold up your own — I have seen that in my mom, I have seen that in my grandma, I have seen that in so many different versions of feminine being presented in different people that I hold near and dear to my heart. Like what Ariana said, it is a duty, and I have to do it because these are the people who helped me. They are the people who got their shit together to get me to where I needed to be. That is something worth talking about. I think we are all kind of struggling together; we all are victims of white supremacy, and I think in a lot of the work that I do, I am actively trying to work towards demystifying what our community is. A lot of my work is very personal, so I am trying to make sure that I know who is in my court. I think it is important to not put those people on a pedestal, but make sure that other people know that they exist. When we think of a community, we use it in abstract, such as the community of Milwaukee. But what does that actually look like? I’m trying to figure out what that looks like to me. So the people that fit within my community tend to be queer and Black or femme, and for good reason. Those are the people that I find a lot of my strength in.

JA: Something that I always look for in work is a sense of urgency, and there is a direct reason for the work to be made now as opposed to ten years from now or five years ago. The reason I really wanted to write about this exhibition in particular is because it is very emblematic of 2020 net large without being, for lack of a better word, pornographic of struggle and conflict. A big reason why I got off of Instagram and I’ve been trying to avoid digital activism is because it comes with a very aestheticized, hyper-focused version of the world, and I have seen a lot of art in the past year that really focuses in on that. But, I think what is happening with Wash & Set is an actual conversation that has nuance.

Also, at what point in your practice did the notion of an autobiographical storytelling and an exposé of the lived experience, romanticized or made beautiful, begin to stretch outside of yourself conceptually? Has it always been something where you are making this work for yourself knowing that it will affect others, or is that something that you are thinking about when you are making works?

AV: Before this I watched a talk between Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson and Faith Ringgold. What’s cool about two artists and friends going back and forth is that you get to see what I really want; what I see LaNia and I as. I want to see that our lives continue to interlock and not just me and LaNia, but a million other awesome and amazing artists. I was thinking about Robinson commenting on this duty to capture a reflection of her Columbus neighborhood. Oftentimes what they teach you in school is to make the work and think about it later, so you don’t get stuck in procrastination while you’re thinking. When you’re making you know that your intention is always there even though you haven’t formulated the language for it. That is one of those things that only time can tell, but I wanted to be taken seriously within history in that realm.

LS: I would say that I feel the same way. It is important to document what is unique to you, but also I have always been autobiographical. I journal a lot, I do sketches, and reading, and just always making time to listen. And listening also meaning observing things that are happening in your life.

Something I have been thinking about very heavily in terms of my work is the access to pleasure, and who gets to frolic in pleasure and experience it. Also, what that could look like in an ideal world, and I think sometimes adding the fantastical elements in my work helps me envision that. Being able to fantasize about something else is a privilege in itself. Sometimes that has to do with taking people from my life that I really respect and care for, and putting them in different compositions, and putting myself in the composition. Just, reimagining myself elsewhere, and I guess that is my long answer to the importance of being autobiographical. Being able to be imaginative, and what does that look like for someone like me?

JA: The pieces in Wash & Set have a sense of returning to oneself, focusing on home, family, and self-care. To what degree do you feel this desire has been informed by the last year, mired by isolation, racial injustice, political unrest, and general exhausting circumstances?

AV: All of it. All of it. How opportunities have come to Black people and other minorities when they are convenient but I think–

LS: How they magically pop up sometimes, especially now–

AV: What I will say is that there were things that were very opportunistic over the summer and we were used for some of it. We were used because we needed money. This show was not exactly like that because this show was asked in advance. I remember being told in college that, in the few times I was given literal information which was actually helpful, an art exhibition should be stated over a certain amount of time. I think both of us are still continuing, and I wonder how many other people of our colleagues are asked to do this, things are just so last minute. Things that aren’t being reimbursed; they don’t have anything to offer and not with good intentions.

JA: When this show was offered, how much curation took place that was outside of the two of you?

LS: I feel like it was more so ‘Hey you guys are extremely close and you guys both pull from the same sort of personal pot of your own experiences. Let’s talk about that relationship.’ Or ‘Let’s talk about how you like to pull from your own life resources.’ I think what is good about being really close is that we kind of trust each other, and the day that we installed we kind of just played things by ear and placed things intuitively.

AV: We also talked about specific sizes and like ‘I am going to work in this size, what size are you going to work in because I don’t want to look crazy.’ If you are going to do something with another artist, it should have a certain series that speaks specifically to one another versus a series that is one-off episodes. As it is kind of episodic, I guess it was the LaNia and Ariana show, but also in our conversations that kind of freedom just put the full reign on us.

LS: Yeah, I think we both wanted to just take this opportunity to make and not really worry about if a piece was successful or not. We both kind of talked about that too; and just being like ‘this has been an exhausting year, I don’t have much creative juice left,’ but also still thinking about it with a lot of intention and care. I think we respected each other’s explorations even though it is, like I said, it is both autobiographical in a sense but it is just translated differently and we use different mediums and whatnot.

AV: You were more responsible in the sense that you had started work earlier. I was in my head like ‘Oh I’m going to get all of my stuff together before I move.’ I had very little responsibilities when I got there because it was almost like a residency for me. I just had time and space.

LS: But you went through a lot of life changes through all of this so it was just different. And now I am going through more life changes, but thank god we are done with the show.

AV: Our work really was created at the exact same time but my pieces were all started later. As we are both Black people, definitely we are exercising what privileges we have, and that’s what forced me to realize that I needed to spend time while I have the resources to do so. These series are both true reflections of this time. That’s what is really cool about this show in particular versus any of the past shows that I have been in. It really does feel like I needed to make it. I was really grateful to have this experience be exhibited.

LS: It was also nice to get a real exhibition other than like ‘hey we are trying to make up for the past fifteen years we were racist at our company, do you want to make a stickman for two bucks?’ That was happening a lot in my vicinity, meaning other people of color. You can’t make up for that in a month when Black people are dying. But, it was different because we have a relationship with Jason Yi (gallery director). It is not going to change because of some social uprising, so that was what made me feel good about that exchange.

JA: Has your art practice affected your relationship with, or how you see, yourself?

LS: I am a lot more comfortable painting myself. I’m getting over that, and not always being the skinniest person. I think that was part of my issue; just having my own body issues but getting over it. Painting my body as is, I think is really important. Especially now, you get more educated about certain things, and why certain people are afraid of becoming fat or gaining weight. You learn that it’s mostly just anti-Blackness and it is all a fucking mess. I have become a lot more comfortable with myself, and that will just keep getting more and more evident in my work. Hopefully in bringing my sense of humor more to my work, that is starting to come together. People that know me look at my work and be like ‘oh, that’s definitely the way LaNia would see something!’ It is sarcastic, ridiculous, but also sweet. It’s like a mixture, but I see myself coming out of the work more. It is becoming more and more authentic, so that is exciting.

JA: Definitely. Thinking about how your practice has become more and more extroverted, and cultivating this garden of expression that you have been making has been a real treat to see. And Ariana, I know you spent a good amount of time in self-portraiture and creating scenes with yourself and loved ones. Has there been an effect from the scenes that you have created over the course of the last few years to now on the way you experience the world, and the way you experience yourself?

AV: Every year it is revealing itself, as you make very personal bodies of work, how much privacy you have. That is something I feel even though, through my writing, I am still grappling with, and expressing certain things. I’m trying to grapple with other creation issues and it is showing me how much this could be the spark which, in the long run, could be a delicious kind of thing. This could be the very beginning and I like the thought of that, and how much pressure that could really take off of me. I can’t see too much further than six months ahead, and while that is very exciting, it also leaves me low. That unknown also reminds me how serendipitous this shit is, and that’s fun. It is hard to think about how much I am going to have to exhaust myself of other resources, and how much I will have to explain myself. But, there are other ways that I do have this freedom which is found by a certain scariness. There is this pressure to fill certain amounts of things, so I will be able to be viewed as enough, so I can get the next thing to hold on to in hopes that it will bring me somewhere else. But, it does make you think about ‘How am I going to sustain this?’ Because this is all I can do, in the sense that this is all I want to do.

LS: It’s kind of true though.

AV: Because you see all of your friends doing well and it’s like, ‘They’re doing well, even when they’re not.’ You go on Instagram, and you’re like, ‘Man, I feel bad’ and that’s all they’re showing, just so that they can feel that little bit of Instagram goodness.

LS: You know I’m sad; I am on medication for depression, and you know I’m dealing with a lot of things outside of the art world. I am not just go-go-go. I’m doing a lot to feed myself, and that’s exhausting. You know, as a kid I thought that’s what I wanted — doing all of these murals and commissions. It is fun, but it’s exhausting. I don’t have any energy left over for myself. I like teaching, but I don’t really want to be a part of a school that kind of lies to kids and tells them all of this hard work is going to pay off. Because is it going to pay off? I hope it does, but I have just been trying to practice being honest and saying ‘make art because you want to, not because you think that you’re going to be famous.’ It is all just very futile, it really is painful.

AV: If people can’t honestly talk about how exhausted you have been — you have been involved in what, four shows this year so far?

LS: Yeah!

AV: Well, what I want is just a little bit of that pie and some time to make the work. Not necessarily just having it look like success, but it is not stability. We did not choose stability, we all chose this. We all went to MIAD. After seeing all of this I know I made the right choice because I don’t know what else I would do. Knowing what the world is, I do know that it was the right choice, but it was not exactly what I thought it was going to be.

LaNia Sproles has a vinyl mural installed at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center in the studio project area that will be up for about a year. She also has an upcoming solo show at the Art Literature Lab in Madison, WI and will be working with Escuela Verde to make a small mural for their new cafe this spring.

Ariana Vaeth has an exhibition, Primary Characters, that is up until April 16th at the Miller Art Museum in Door County.

Both artists have work the show Unraveled. Restructured. Revealed, curated by Tyanna Buie, at the Trout Museum of Art in Appleton, WI.

Featured Image: LaNia Sproles, Bu$$y Fount@in, 2021. Intaglio print, gouache, collaged cut paper, blue film. Various figures are seen frolicking in a large fountain as blue water flows around them. In the lower left, a figure in a colorful-patterned outfit sits at the edge of the fountain, holding a water bottle and looking towards the viewer. Photo by Joe Acri.

Joe Acri is an artist and organizer in Milwaukee, WI. He is the owner and co-curator of Gluon Gallery and a lead organizer of the Grilled Cheese Grant, an annual community fundraising event and emerging artist grant that provides financial support for undergraduate seniors at MIAD and UWM who are completing their senior thesis projects in the areas of Fine Arts and Design. His work as a curator and organizer is focused on accessibility and diversity of voices in art spaces.