It’s an unseasonably warm December morning and I’m driving cautiously through a Chicago warehouse district, south on Ashland Avenue past an overpass of the Stevenson expressway. The slice of the interstate makes this patch of the city feel like a peninsula, jutting timidly into a convergence of two stretches of the Chicago River. My directions lead me down a small road innocuously named Marketplace Access, past the slick corporate bulk of the QTS Data Center campus, and I’ve arrived.

I join a group of about forty light-jacketed companions at Canal Origins Park for a walk through the city’s history of timber extraction with Deep Time Chicago, a collective of ecology-minded artists who want to retrain our awareness to our surroundings, and the artists Sara Black and Raewyn Martyn, whose joint installation Edward Hines National Forest is on view at the Hyde Park Art Center.

The park commemorates the point where the Illinois & Michigan Canal once connected the Great Lakes with the Mississippi River drainage basin. It’s an impressive sounding spot, but if I’ve ever been this way before, I’ve never noticed it. That flicker of awareness, the suspicion that I’ve been blind to something entirely present right in the middle of the city, is a fitting preface to the day to come.

As we mill about, I peruse a long didactic panel, slightly obscured by weather and graffiti. “The Illinois & Michigan Canal began here, and so does Chicago’s story,” the panel explains. For someone with deep time on the brain, it’s fitting that the panel traces this spot from prehistory to the present with neat linearity. The park, it boasts, is “the place where water connections transformed Chicago from a tiny trading post into a national crossroads.” The story of Chicago is embedded directly in the land.

That premise is the starting point for Deep Time Chicago’s practice. “Not just the urban surround,” their website reads, “but the entire global ecology has become an artifact of society.” This is the distinguishing feature of the Anthropocene, a somewhat controversial scientific concept that human intervention has imbued the structure of the planet—its geology, biology, and atmosphere—with such force and permanence that our era requires its own designation. “Anthropocene engineering changes the fundamental structure of the earth,” Brian Holmes, a founding member and one of the primary guides of today’s walk, explains to the assembled group by way of introduction.

As we move through the park, Holmes, Black, and Martyn teach us about the landscape around us. Across the water is the former lumberyard of the Edward Hines Lumber Company, the entity responsible for deforesting Wisconsin’s old-growth Northwoods in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Before settlers arrived, the site was an intersection of forest, waterways, and western savannah and prairie ecosystems. By the mid-1800s, this fortuitous situation was considered providence by the settlers: God’s wish for Manifest Destiny. “The landscape formed a sense of vision for how to use the landscape,” Black explains. To settlers, and later, to corporate interests, the land was communicating its own consent, giving permission for its own use.

Artists’ explicit engagement with questions of ecology have existed at least since the beginnings of the discipline in the 1960s (and artistic meditations on the nature of nature have existed as long as art). Deep Time Chicago traces its origin to a 2014 convening of ecological thought called the Anthropocene Campus, initiated by Berlin’s Haus der Kulturen der Welt and the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. The seminars generated a global, interdisciplinary movement of ideas around the Anthropocene among climate scientists, artists, and cultural theorists. The ideas stuck; two years later, at the follow-up Campus in 2016, two of the ten seminars were convened by Chicago artists. They established Deep Time Chicago to further this expansive form of inquiry.

How does one respond to planetary upheaval? “The subject is so rich that it allows the projects to expand rhizomatically,” Holmes tells me with excitement. Human intervention is undeniably present around us, and grappling with it requires experimentation in form. The literature on the field is abundant, from scientific texts to eco-poetics. Feminist and Marxist critiques remind us the blanket term “Anthropocene” may mask the power imbalances that ensure certain groups of people share the bulk of the responsibility for the transformations, while others bear an outsized burden of their effects. Other names have been proposed to reflect this, from Capitalocene to Chthulucene and beyond. For the young collective, much of the current dialogue is working to mold the direction of its own efforts.

It’s hard to pin down exactly who’s in the collective; membership in the group is—what else?—“organic,” as Holmes emphasizes. It comprises a handful of core members, some of whom attended the Campus, alongside frequent participants in Deep Time events and others who attend on a more casual basis. Artist Jenny Kendler puts it succinctly: “The group is anyone who shows up and does the work.” Each has his or her own independent practice but sets aside energy for collaborative and generally public-facing activities.

Holmes addresses the assembled group along the waterway. “We don’t want to know about the connections between our past our present and our future,” he laments. In the face of this dangerous, willful apathy, the collective calls for “first person science”: direct sensory perception of the world around us. Though this specific walk is not strictly a Deep Time Chicago event, since it’s run in conjunction with an outside exhibition, the group has organized several similar walks around Chicagoland, from the Morton Arboretum to the forest site of a buried nuclear reactor.

Places like this—places that question the nature we think we see—are abundant. “The Midwest is the area in North America that has the most human intervention,” explains Kendler, calling the group’s angle “specifically Midwestern.” In some ways, the very premise of the Anthropocene throws into question just how comparable human intervention is in different regions. Presumably, nowhere is pristine, try as we might to forget this on a stroll through a city park. But looking around at the locus of I-55, countless stretches of train tracks, a canal that’s diverted the river from moving water into Lake Michigan to draining waste back the opposite way, all of which is surrounded by anonymous parking lots, belching smokestacks, and acres of cold data storage, it’s hard to disagree that there is something especially potent here.

Sara Black, based in Chicago, and Raewyn Martyn, from New Zealand, brought us here to tell one such Midwestern history. Standing near the site of the Edward Hines lumberyard, now home to Chicago Yacht Works, I’m transported back to their work in the Hyde Park Art Center, a few miles south of where we’re standing. If a lumberyard is the site’s not-too-distant past, Black and Martyn’s installation is perhaps what a forest looks like in the deep future of the Anthropocene imaginary.

Black notes that Hines’ company “wasn’t seeing trees, they were seeing lumber.” So are visitors to the gallery. Their massive structure is made of the region’s pinewood and nailed together like our ubiquitous Balloon Frame construction. But this is no laborer’s home; wild wooden angles are draped with translucent, peeling sheets of swirled color made of cellulose-derived biopolymer paint. A precariously lofted pine bridge offers access to the airspace of the double-height room.

If bureaucratic endeavors transformed wilderness to wilderness preserves, enclosing a section of nature before loggers have the chance to swing their axes, Black and Martyn have built a landscape from a time long after industry has ransacked the area, reconstituting “forest” with material on hand as though according to a hazy, half-remembered description of one. The installation is an unsettling promotion in the shape of a tree house.

But back out in the raking sunlight of Hines’s now-treeless home turf, I try to ground myself in the specificity of this place, this moment. It is a process of sensitization. It’s also surprisingly somewhat difficult. Despite being at such a historically important site for the history of the city—and of European settlement in the region—the spot looks like absolutely nothing important at all. Deep Time Chicago is well aware. “A story is told but the material reality is totally neglected,” Holmes says to the group, gesturing at the nondescript land around us, “Where was the canal? What space are we actually in?”

Periodically, we break from walking for Black and Martyn to elaborate on the pages of handouts they’ve distributed (including, perhaps ironically, a map of the continent’s paper pulp mills). The readings and lectures, charts and graphs remind me of an especially fun day in a grad seminar; the rigor gives off the vague sense of a parallel academia. Indeed, many of the members of the Deep Time Chicago are professors.

Yet Jeremy Bolen, a founding member of the collective and faculty member at SAIC, emphasizes that Deep Time Chicago is committed to bringing these ideas “outside the walls of the university.” It’s clear that these institutions have quite different approaches to similar material: Bolen noted for instance, that as we were walking, the University of Chicago was celebrating the 75th anniversary of the first plutonium-producing nuclear reaction by hosting an artistic recreation of a nuclear explosion and a talk by the CEO of the energy corporation Exelon. The politics of the collective require a critical stance toward the institutional production of knowledge.

Open-ended inquiry is the day’s methodology of choice to orient us toward the narratives that structure land use. As we walk, participants freely share their own curiosity (“What’s the status of the Asian carp?”) and the artists offer structured provocations in an attempt to reframe that environmental perception: “What is happening here?” “How to live inside the big dry and big wet?” “When do we celebrate?” As we discuss, artist and Deep Time Chicago member Amber Ginsburg reflects on less obvious forms of human intervention: “The governing bodies of this river run extremely deep.” The group lets out a collective, knowing hum.

It occurs to me that there’s something productively absurd about the name “Deep Time Chicago.” How to reckon the profoundly immense “deep time” with the something as embedded in cultural and historical circumstance as Chicago? It sounds as though the entire archive of geologic time could be housed in special collections at the Harold Washington Library.

The collapse of the unfathomable and the quotidian is apt; it forces us to look at the whole city, each material particle, as part of the span and scope of the life of the Earth: something both extracted from and active in the ground and surrounding ecosystems. Standing in the breeze, sandwiched between Chicago Yacht Works and the QTS Data Center, it’s suddenly impossible not to see the land as a product not just of two waterways joining up, but also the convergence of material construction, financial development, and cultural narratives.

Direct sensing, as performed in the collective’s walks, gives us access to less straightforwardly spatial human constructs as well. The land’s transformation from lumberyard to luxury manufacturer, from heavy industry to information hub, manifests as a bend in the flowing story of accumulation. Holmes, perhaps similarly struck, turns the group’s attention to the Sears Tower visible behind us, a looming tribute to financial capitalism. “The city continues to radiate out into the world,” he says as we meander back to our cars. “What can we do to think about the city’s role in the world and not just on a Saturday afternoon?”

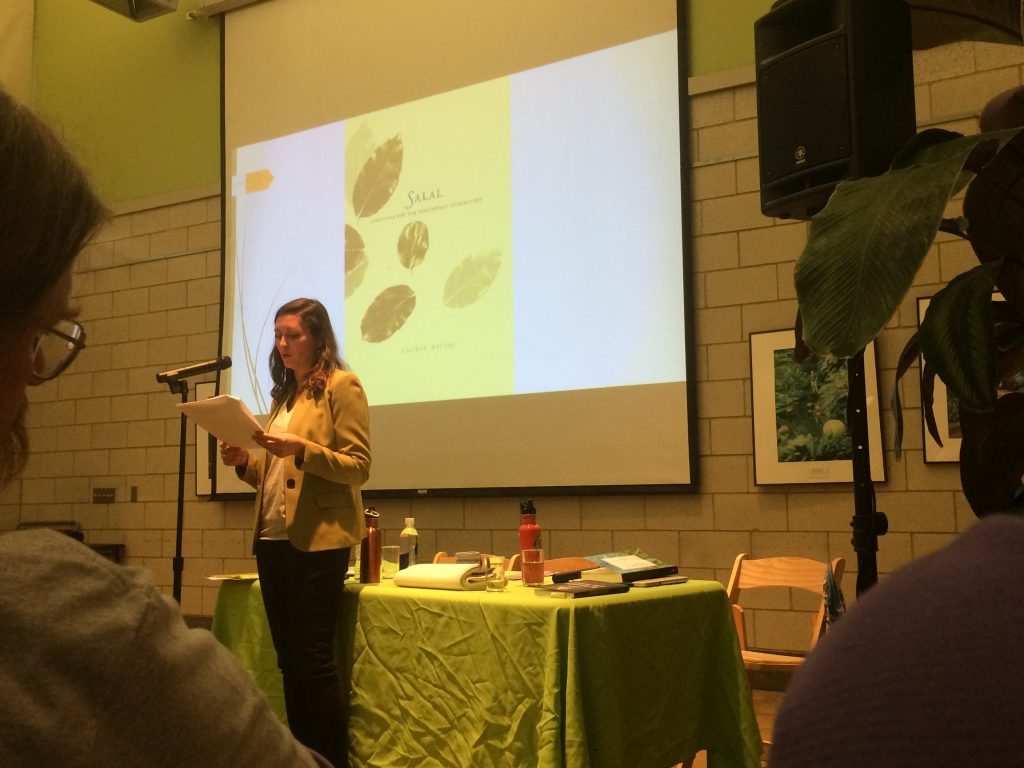

I look forward to considering the question. But for now, the afternoon isn’t over quite yet. After a quick lunch, I head back out for the collective’s afternoon panel discussion. It’s at that most cultured of nature spots: the Garfield Park Conservatory, where Deep Time Chicago member Claire Pentecost is its inaugural artist-in-residence. True to form, she is using the opportunity to foreground the ecological voices of others. This afternoon, we’re treated to short presentations by Wendy Makoons-Geniusz, director of American Indian Studies at the University of Wisconsin, Eu Claire, and Aubrey Streit Krug, a postdoctoral fellow in Ecosphere Studies at the Land Institute in Salina, Kansas.

Both women bring with them scholarship on relationships to nonhuman life in North American indigenous thought. Makoons-Geniusz reflects on Anishinaabe teachings through the lens of the Ojibwe language, explaining the Four Orders of Life that categorize the agency inherent in everything from mountains and rivers to trees and animals, and even foundational stories themselves. In contrast to Western anthropocentrism, humans are in category four of four: “It’s not a hierarchy, but if one is least important, it would be us,” she deadpans. Later, Streit Krug offers her own meditation on communication with the nonhuman. She compares the English word “plant” and its pedestrian, settler colonial etymology, with the finely attuned specificity of the Omaha language. Her solution? “Listening in an immersion experience.” The sentiment feels very much in line with our day of Deep Time.

Following the presentations, the crowded, humid room becomes the site for a fluid exchange of audience members asking questions, offering thanks, and musing on their own relationships with nature, language, and spirituality. Pentecost asks the speakers if they have noticed a recent uptick in ecological awareness. “If you look at all of human history,” Streit Krug replies measuredly, “it’s only a relatively small group of humans in relatively short period of time who have distance from the nonhuman world, who don’t understand this connection.”

I’m still turning over this idea—so fundamental yet somehow eerily simple to overlook—when I revisit Black and Martyn’s installation the next day. The cheeky title begins to feel lucidly sinister. Afterwards, as I leave the Hyde Park Art Center, I walk past a cluster of identical high-rises each called Algonquin. Just one day immersed in the collective’s work has reminded me that heavy cycles of exploitation and entanglement pervade land use, language, and layers of time. It’s a form of privilege to be able to forget that these cycles are everywhere, baked into clear-cut forest and towering development alike.

Perhaps the most fundamental lesson of Deep Time Chicago—and the reason the group’s expressly interdisciplinary approach is so intriguing—is that the effects of human intervention extend beyond the quantifiable. Boating down the canals of deep time must also be a practice of attention and exchange. To confront material realities of ecological disaster requires decolonizing both infrastructure and the structures of language and thought, so that we might see alternatives beyond those that reversed the river, drained the prairie, and settled the land.

I think back to Holmes’s original question: “What space are we actually in?” The answers span millennia in all directions; the first step to finding them is to start walking.

Featured Image: A handout featuring photographs of the Edward Hines lumberyard held up in front of the site’s current tenant, Chicago Yacht Works. Photo by Nina Wexelblatt.

Nina Wexelblatt is a Chicago-based writer and curator interested in the intersections of art, ecology, and technology. She is the current Curatorial Research Assistant at the MCA Chicago. Nina earned a BA from Yale and MA from Williams College. You can follow her on Twitter @nina_rrose.

Nina Wexelblatt is a Chicago-based writer and curator interested in the intersections of art, ecology, and technology. She is the current Curatorial Research Assistant at the MCA Chicago. Nina earned a BA from Yale and MA from Williams College. You can follow her on Twitter @nina_rrose.