My first experience with AJ McClenon’s work happens to be my most memorable. It wasn’t as part of an exhibition or screening, but while quietly seated in public solitude, headphones on and computer screen inches from my face. The first time I watched the collage video Things to do like breathing it set the tone for how I now prefer to view the videos and audio tracks–by bringing it in close, almost inescapable, sensory proximity. At that all-consuming distance, partially immersed but still aware of my surroundings, is where the core of the work presents itself–at least to me. It was there where my own anxieties found something familiar.

McClenon’s layering of sound and image, and use of repetition creates a hypnotic agitation that is a signature of the work, particularly the time-based pieces. The form of the videos thickly coats the content, providing them a lens that works to help us as viewers to understand how things like the struggle with mental health, a shifting sense of belonging, and the jurisdiction we have over our bodies and lives impact how our stories can be told. It’s artistry that requires us to look and listen closely for not only the obvious or more covert narratives, but also how they’re being delivered. It can be easy to miss the message by reading it all as purely personal. Sound, image, and autobiography aren’t the only things being stratified. Scratch the surface and underneath you’ll find archives of McClenon that expand beyond a singular voice and into something that bridges a distinct east coast/third coast understanding and a historically-informed, contemporarily-centered but deeply personal exploration of the nuances of Blackness across spectrums of age, gender, wellness, and other ways of being.

As McClenon continues to build a presence across the city, we took some time to discuss how the current practice has evolved from focusing primarily on sculpture and painting to video and sound, the ways in which health can impact life and art-making, the ongoing efforts to collapse hierarchies, and the variety of narratives and storytelling techniques stretched across these different bodies of work.

Tempestt Hazel: From your 202 area code I suspect you might be from Washington, D.C., though you went to school in New York and Maryland. Where did you grow up and what path landed you in Chicago?

AJ McClenon: I am proudly from D.C. and I spent my summers since I was about 7 in Baltimore and New York to be with my aunts.

In high school my Mom enrolled me in the Upward Bound program through the Latin American Youth Center (LAYC), which is in an area of D.C. called Columbia Heights. The program held academic Saturday classes and college prep programs at GW University for students from low income families. When applying to colleges one of the mentors at LAYC, Mirna Turcois, suggested that I look into The New School’s liberal arts college, Eugene Lang College, where she attended. After taking the college tour at Eugene Lang, it became my number one choice, but because of my subpar grades from a record of skipping classes during high school I was put on the waitlist. But my exams, extracurricular activities and me flooding the admissions department with emails got me in for the following semester, which began in January of 2005.

I was excited about the small classroom sizes and the emphasis on writing but I was also struggling with crippling anxiety. Before I left [for Eugene Lang] I had my first panic attack on the New Year of 2005 and ended up at Howard University Hospital. In New York my anxiety also took the shape of claustrophobia, so I began to avoid trains and elevators, and even trips going home to D.C. became difficult. It was really hard to socialize with these limitations and with the panic attacks. By my third semester I decided to try to transfer to the University of Maryland, College Park (UMDCP), which isn’t very far from my D.C. home. At the time all of my roommates in New York went to Parsons School of Design at The New School and I became fascinated with their late night projects and talks about critiques, artists and fashion. So I applied to UMDCP as an art major.

The program there was open in that I was able to delve into projects from metal sculpture to painting to video work. I eventually minored in Creative Writing after taking so many writing courses and joining the Jimenez-Porter Writers’ House residency program. After moving back to D.C. and attending UMDCP, my anxiety eased up somewhat for me to make genuine long term connections in the art department. But after another severe panic attack my anxiety and depression hit an all time low. I had to decrease my academic workload to 12 credits per semester. Even though I could barely leave the house post-graduation I still began to apply to graduate programs across the country, despite my fears surrounding leaving the house. Before graduating in the winter of 2011 I made meetings with professors about where to apply to. At the time artist, Hasan Elahi was teaching there and he suggested that I apply to SAIC’s writing program and to take advantage of their allowance to be flexible within other departments in order to think of writing and storytelling through different mediums. With that suggestion, my intuition and the funding that SAIC offered I decided to face my fears and move to Chicago.

TH: So, time-based media wasn’t the first art form you worked in. You found it eventually after working in other ways?

AJM: I initially gravitated towards sculpture and metal casting when at UMD. I really enjoyed the aspect of play with found materials and its transformations. One of my favorite projects was taking cassette tape ribbon and meticulously gluing them together using foam to hold the strips together. I used the colorful ends that you find in some cassette tapes (blues, yellows, reds) to contrast with the browns. The final product had a leather texture and it also created a fringe effect with the parts that remained unglued. I was really into the redundant almost obsessive process. I was also fascinated with this idea of reconstruction after the deconstruction of materials–like taking the leather off of hymn books donated from my Grandma’s church, replacing the bark of a tree trunk and infusing tambourine cymbals in the cracks of the tree which articulated a sort of bent metallic growth from it. I always wanted to make this project bigger, so maybe that’ll be a plan for a near future project.

With metal casting I got really into portraits, with a heavy emphasis on exaggerated facial features, using my grandma’s face as inspiration. [I also got really into] hairstyles; making metal cornrows for an aluminum piece that’s still resting at my Grandma’s house. I would cast mostly in aluminum and sometimes in bronze when I could afford it. During my sculpture days – which may come back around – I worked closely with artists and teachers, Foon Sham and Steve Jones.

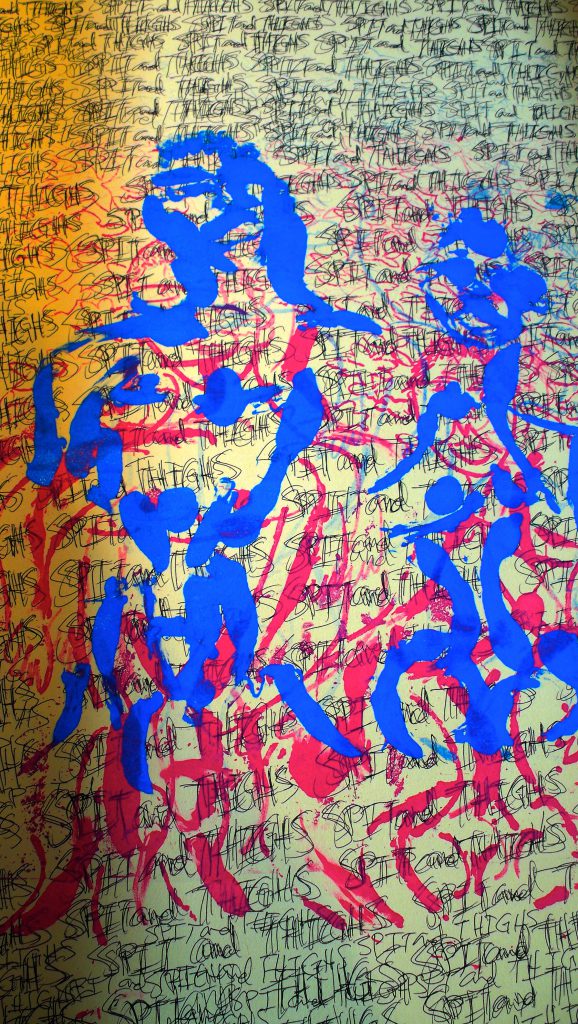

I wanted to try printmaking and take advantage of the facilities at UMD, so I took a lithography class and began working closely with teacher and artist Margo Humphrey. She encouraged me to draw more and reminded me to focus more on the process and to trust my intuitive hand with creating images. I began to do that with painting as well, working with teacher and artist, W.C. Richardson during my last two semesters. I worked only with acrylic paint instead of oils and would also use ink, spray paint and other found materials. When I paint I like to use thick coatings of everything, using lines, Black bodies & faces, texts on top of texts and mostly primary colors. Painting and drawing began to help me tie together some of my interests, including writing, science–biology and geometry more specifically–and music.

For my last year I wanted to create a comic book using a story that I wrote and did an independent study with Jefferson Pinder, who after looking over a few of my sketches suggested that I look into animation. I ended up creating my first stop-motion animation, Traveling, using Barbie dolls and hand made sets from cardboard. I fell in love with the tediousness of taking frame by frame to the editing process and the aspects of drawing and painting for the sets. I was also excited to use my writing to tie together scenes through narrative captions.

After coming to SAIC and having access to more video equipment and editing software, I began using live video footage. I also took a lot of sound classes with Mark Booth where I began to work with the storytelling process through sound. It really transformed the way that I thought about writing and communication, not just beyond pen and paper but also beyond words as language.

Cornrows, aluminum, 2007. Image Courtesy of the artist.

TH: What was it about sound and film that drew you in?

AJM: Everything begins to come together with video and sound. Editing both sound and video feels a lot like sculpture in the [way it requires the] breaking down of original forms. By the time I moved to Chicago, anxiety with panic attacks had been an active part of my life for about seven years. Video and sound began to capture the components of anxiety that I wasn’t able to fully communicate otherwise. The high vibrations of senses, the tunneling sensations, the claustrophobia, the control through avoidance and food, the agoraphobia; video and sound became a language for me to articulate these experiences.

Just walking around was oftentimes a challenge for me and after the passing of my step-dad, who I called my godfather, a month after moving to Chicago, the grief shook me hard. I couldn’t cry for almost a year or bring myself to get home for the funeral. I began to record my time on the bus and at the grocery store, make loops from the sounds and compose those loops into a layered track along with my voice. I got really into sound before thinking about video. It felt safe. Making these loops and soundtracks originally from spaces that caused me a lot of anxiety and turning them into soothing rhythmic loops created an alternate pathway into the outdoors in a way.

TH: Other than what can be seen in your animations, what overlap is there with your time-based work and your painting/drawing practices?

AJM: Editing sound and video feels very much like painting/drawing to me. The heavy layering of materials. Silence used in sound just as negative space is used in the composition of images. You’ll also find a lot of the same colors that I like to use in paintings that are in my videos– primary blues, yellows, reds and greens. With these color options it can be both very serious and very youthful to me. With video, I really enjoy using the GoPro camera that doesn’t have the viewer screen so that I can explore and draw out moving images later through editing. Much like painting, with video and sound I’m not much of a planner. I really enjoy building something from many other pieces that I collect throughout the days. It’s the same with painting. I know that I want to talk about shapes, lines, dimensions, and the navigation of Black bodies through those spaces. But one moment I will collect acrylic brush strokes and then another day I’ll place a flat piece of metal on top, then I’ll layer that with a ninety degree line and two figures. Then, it’s the same with video. If something’s upsetting me from what I hear on the news, I’ll think of footage that I took that represents that feeling and then layer it with a sound and continue on.

TH: Naturally, writing is also a big part of your practice. What forms do you work in?

AJM: I really enjoy broken narrative. Using poetic forms to write a longer story that works outside of linear time. For some time now, about 3 years or so I’ve been writing a longer narrative piece that is composed completely out of linear time where the narrator speaks disjointedly through flashbacks and current time in discussing their movement through the world as a Black and queer person, a sex worker, and their encounters with those living and dying around them.

I’m also very interested in oral storyteller as a form of writing, critical writing in response to politics, culture and current events and linear prose.

TH: I’m curious about what are you reading, listening to, watching?

AJM: I really enjoy reading nonfiction and looking at science journals from human biology, public health, astronomy and technology. It’s nice, too, to look at historical scientific texts and see similarities to now, predictions of the future and shifts that occur–especially during certain political climates throughout the world. I also like to read autobiographies written by Black authors, coming-of-age-stories, and fiction that uses themes of Blackness and youth.

Right now I am reading The Awakening by Oliver Sacks, Spill by Alexis Pauline Grumbs and Black Looks: Race and Representation by bell hooks.

I really enjoy reading song lyrics too. I like to listen to hip hop, rap, punk, free jazz, funk, and I’ll check out anything that pushes and fuses genres together. I love music and sound, so I will always dig deep to explore new sonic sensations. Right now I am listening to the Boredoms’ album Vision Creation Newsun.

I also like to watch independent films and TV when I have the time and I love digging around to find vintage home movies, old political clips, vintage scientific footage and things like that. I also love watching music videos. I’m also a big fan of Pam Grier and the blaxploitation films she was in.

Recently, I finished watching the TV series Westworld and I loved the writing in that.

TH: To build off of that question, where do you draw inspiration from–other than maybe the things you’re reading, watching, and listening to?

AJM: I draw inspiration from what I am paying attention to within different media, conversations, history, science, personal events, experiences, and also what is happening here in the United States and globally.

And although I don’t listen to the radio a lot these days, it was a huge part of my life growing up. [I used to] listen to radio shows with my grandpa and I tend to think about those times while storytelling. Sound is a huge inspiration for all of my work, even when I’m working from a visual perspective. I listen to music while I’m painting and when I’m shooting videos, too.

TH: Front and center on your website you mention that you’re interested in leveling and collapsing hierarchies of truth by placing scientific data alongside your own personal experiences and histories. How did you arrive at that point of inquiry?

AJM: There are some instances where truth is relative, then there are instances where the relativity of truth becomes dangerous and where systems are created to speak to and to “educate” the masses with what they deem as valuable or factual truths that don’t reflect history or the lived experiences of the lives that are underrepresented and [often not] present in positions of power.

TH: Why is collapsing hierarchies and understanding personal narratives as a form of truth important to you?

AJM: As much as I really enjoy science, it has a tendency to become disconnected from intuition and sources of empathy. There’s a constant hunt for proof that seeps into systems in a way where someone is saying, “this isn’t working for me (us)” or “I am hurting,” where there’s not an active response to find new systems because it can’t be “proven” that these systems are hurtful and broken.

As a Black queer person whose narrative is constantly under scrutiny and investigation, whose narratives are muted, hijacked, written off as fictional, continued as untold, information and truth continues to be important to me for what it stands for and for what it doesn’t stand for. I think a lot about valuing truth as experience above truth as lies and truth as oppression through religion and laws.

TH: One thing I love about your work, particularly the narrative work, is that, to me, much of it poses questions or gives a sense of curiosity and discovery rather than imposing a set idea. There’s an approachable uncertainty that’s felt from you as the artist and conjured for me as the viewer, and you apply it to talking about human dynamics across lines of gender, age, race, geography, time. You seem to create from a place of vulnerability. Does it feel that way when you’re making the work?

AJM: It does feel vulnerable in the way that I am being led by my curiosity. I approach a lot through questioning. Even though I am interested in a breakdown of hierarchies I know that I can’t achieve these breakdowns alone but I can question them. As a Black person, I get questioned often. My body is questioned, my intellect is questioned, my presence and existence is questioned, my questions are questioned. Culturally, through my own experiences and observations, I’ve noticed that Black people have been taught to fear our curiosity, to fear our voice and to fear our stories so we often [only] tell them to one another. But what does it mean to discover and question ourselves and then to question the world around us–[question] what we fear and [question how] the world fears us? [What does it mean] to discover our own fears within ourselves and to make these systems accountable for them?

TH: You keep bringing up storytelling, which is at the center of much of your work–even the titles of your paintings and drawings are almost short stories. But with your film and video work, the narrative is often disjointed, offering only small fragments that seem to come from memory. Form and content seem to be feeding off of one another in a very direct way. As a filmmaker, why do you choose to disrupt and dice up the traditional linear narrative approach?

AJM: I think I was in junior high school and we were talking about story arcs and mythology–or something like that–and one part that I picked up was this idea of returning home. Leaving home to find home and to return home again and that’s kind of stuck with me in the way that I read, write and make work. Leaving something to return to the beginning of it and to leave it again in the same way or in a different way or to not leave and to leave from a different home.

Also, thinking about memory’s role in how we grow–whether it be physically, mentally, or spiritually. We may feel more advanced or more grown up than we did a few days ago or a year ago, but then an experience or a previous memory comes up and transports us beyond the kind of linear existence that we find in physical and emotional aging. I am very interested in articulating our looping existences through personal experiences, politics, and histories.

TH: Tell me a bit about your performance work. Does it cross over somewhat into the video work as well?

AJM: My performance work, unlike my video work, is much more improvisational and usually not accompanied by video. But similarly, it works towards non-linear storytelling.

I fuse together poetry, personal texts, and interviews with activists and community organizers with music from various genres, pre-recorded compositions and sometimes live instruments. Lately, I’ve been working with a mix-deck as a device to integrate these sounds together presented as a DJ set.

The themes presented usually cross over and align with what I talk about in my video work, but the outcome of the performance work is independent from video.

TH: Your sound work moves between being surreal soundscapes to musical tracks. What role does music play in your practice–do you see yourself as a musician or composer?

AJM: Music plays a huge role within my practice. I do think of myself as a composer in a non-traditional sense. I play the guitar, piano, and harmonica by ear–and any other instrument that I find access to. I sometimes use these sounds for videos and during performances. I take sounds from the grocery store or the bus and create looped rhythms as well as creating sound loops from video footage. I’m also very interested in echoes and created presenting sounds as if they’re coming from underwater.

I do think of myself as a composer in in the way that I am arranging sounds to create a track. And, I guess, I feel more like a musician when sound arrives pre-edited and through improvisation. That’s not a general distinction of what I think a musician is versus a composer but a distinction I use for myself.

TH: Speaking of sound, you often use and distort your own voice in your videos and animations, which reinforces your interest in combining a personal narrative with found footage. Are there other reasons why you maintain your voice as the primary narrator?

AJM: I really enjoy using my voice as an instrument of its own and its attachment to my own personal narratives and stories. Currently, within my live performances I use a mix-deck and I’ve been integrating other voices from NPR podcasts, political and community activists, feminists, news clippings and the voices of other musicians such as Leadbelly and Albert Ayler.

TH: Sometimes you separate out your sound compositions from the video or visuals that they are combined with in other pieces. I like to think the sound as a stand alone piece allows for a kind of focus and imaginative scope that isn’t always allowed through video. What does that separation reveal to you in how you read the final and separate pieces?

AJM: For me, I am thinking about a few things when separating sound from video. I like to think of the isolation of senses. Experiencing sound and image together, then sound alone. I also think a lot about growing up and spending time in different cities during a time where hyper-awareness was necessary. [During those times you’re] always being cued in with what you can hear and not see and vice versa. Or there’s how the city moves into private spaces like the home.

TH: When you know they are going to potentially function separately, does it change your process and approach?

AJM: Yes–especially if I am working with live sound. I find that my edited videos [are sometimes] carried using looped sounds or something more consistent and steady. And, sometimes, that will also happen with just standalone sound work where there’s a narrative voice component. I’ll use a streamlined rhythm or beat that continues or goes in and out. But with live sound, there’s much more of an improvised integration.

TH: What is your research process for the found video footage and audio tracks you incorporate into your work? In other words, how do you find those clips and samples?

AJM: I’ll record sounds and video during my commute and loop them to make my own rhythms, and visual patterns. But I really love research, so I’ll dig around on Youtube and public archive sites like Internet Archive and Media Burn. Research is nice because it’s not always about finding samples but learning about musicians, activists, and events that have occurred and noticing cycles within current and historical events. Recently, I learned a lot about the late Dovie Thurman and her community work here in Chicago during the 60’s which then led me to Studs Terkel’s work, which then led me to the Chicago blues and jazz musician Blind John Davis–the research channel continues to grow deeper. I used these samples for my first two live DJ sets.

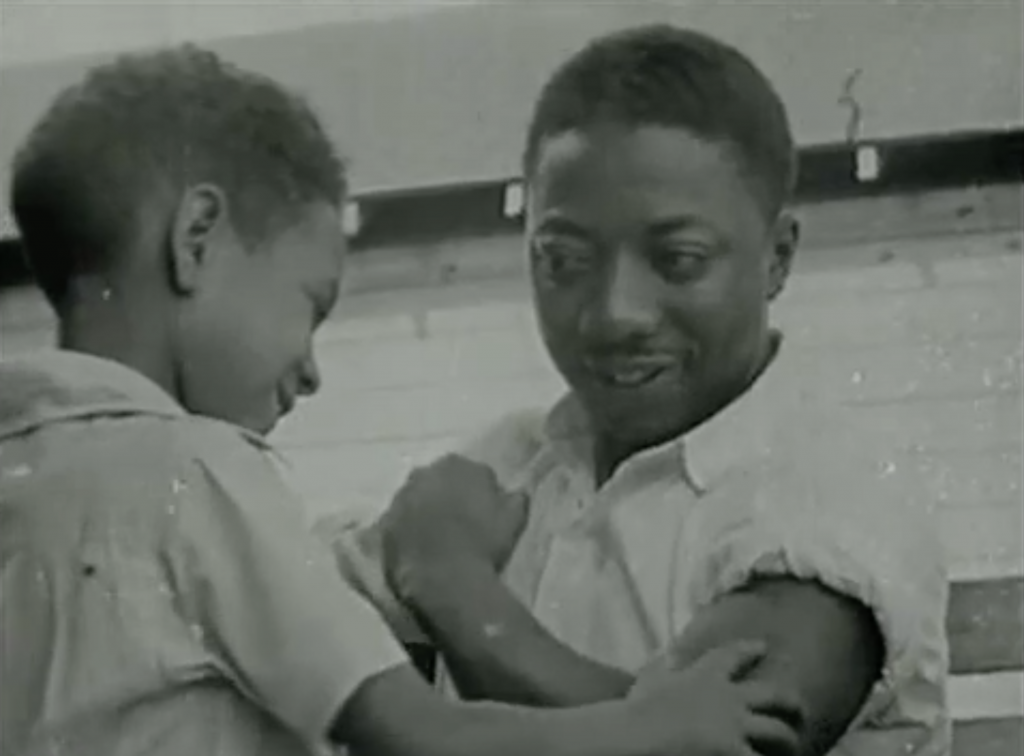

For my last video, Black Water Midnight, I interviewed a few friends and my grandmother about their experiences swimming as Black people and used their voices with found video footage that sampled a hearing from the Lead Contamination Control Act of 1991 at the Supreme Court as well as footage from Castle Films’ Sportbeam. I really enjoyed the approach of sampling voices of people that I know and interact with beyond myself.

TH: You’ve made or shown your work all around the city in places like Chicago Filmmakers, Defibrillator, ACRE, Woman Made Gallery, BING Art Books, Nightingale–the list goes on. As a transplant to the city, how has a varied practice like yours been supported? How has your experience been finding places to support your practice?

AJM: I feel like moving to another city as a student made it easier to initially find support and community, which has been a privilege–to have the opportunity to transition in that way. Beyond school, it has been very valuable to learn how to write and talk about my work. I have learned that mostly from sending out applications and documentation. Like any artist, I have to continue to remember to not get discouraged by rejections and to stand behind my work. And to allow room for the evolution, collaborations, and community that comes along with making and creating.

All in all, I have felt supported and as someone not originally from Chicago I enjoy and value discussions with people who are from here about the differences and similarities between east coast cities and those in the Midwest, and [also discussing] the waves of gentrification sweeping the country and the entanglements of art spaces and artists within these waves.

TH: Outside of being a maker, you also help provide space for other people to make work, right? Tell me about your involvement in Beauty Breaks.

AJM: Beauty Breaks was originally founded by Amina Ross during her research and residency at the Stony Island Arts Bank and as it has continued to grow. I work as the co-organizer along with Amina and the Community Program Apprentice, Jamillah Hinson. Beauty Breaks is a participatory art project that has taken the form of an experimental workshop series. The workshops bring together artists, educators, and beauty + wellness practitioners to break open what Black beauty and wellness means to Blackness today. These workshops and participatory performances center Black femininities and are free and open to the public. Workshops have ranged from sessions on hair braiding and intimacy, to workshops on indoor vegetable farming, original vegetable and bone broth making to spiritual cleansing through meditation.

We create a learning exchange with communities from various backgrounds, gender spectrums, and age groups where feminist thought and Blackness lie at the crux. Facilitators and attendees must identify with both cruxes. Beyond a growth that we find within ourselves and those involved, and beyond a geographical growth, we will evolve and learn from the communities that provide us with the gifts of intimate collaboration.

TH: And, finally, there’s F4F. Can you talk a bit about that space?

AJM: F4F is a domestic venue. We cultivate a femme community, we center Blackness, and we expand upon understandings of what domestic space can be. F4F is a living space where local Chicago artists and community organizers, Ally Almore, Jory Drew, Janelle Miller, Zach Nicol and Amina Ross curate, host and organize events and performances in our attic space in Little Village. We all have deep desires to bridge a gap between the Chicago artist transplant community with those that have been here already.

Experience more of AJ McClenon’s work by visiting ashleyjmcclenon.com, and learn more about the collectives of people making embracive space to explore ideas/practices centered around beauty, wellness, Blackness, and migration of all kinds by visiting beautybreaks.info and femme4fem.me (F4F).

Featured Image: Portrait of AJ McClenon at Beauty Breaks. Photo by Ally Almore.

Tempestt Hazel is a curator, writer, and founding editor of Sixty Inches From Center. Her writing has been published by Hyde Park Art Center and the Broad Museum (Lansing), in Support Networks: Chicago Social Practice History Series, Contact Sheet: Light Work Annual, Unfurling: Explorations In Art, Activism and Archiving, on Artslant, as well as various monographs of artists, including an upcoming book by Cecil McDonald, Jr. published by Candor Arts. tempestthazel.com (Photo by Zakkiyyah Najeebah.)

Tempestt Hazel is a curator, writer, and founding editor of Sixty Inches From Center. Her writing has been published by Hyde Park Art Center and the Broad Museum (Lansing), in Support Networks: Chicago Social Practice History Series, Contact Sheet: Light Work Annual, Unfurling: Explorations In Art, Activism and Archiving, on Artslant, as well as various monographs of artists, including an upcoming book by Cecil McDonald, Jr. published by Candor Arts. tempestthazel.com (Photo by Zakkiyyah Najeebah.)