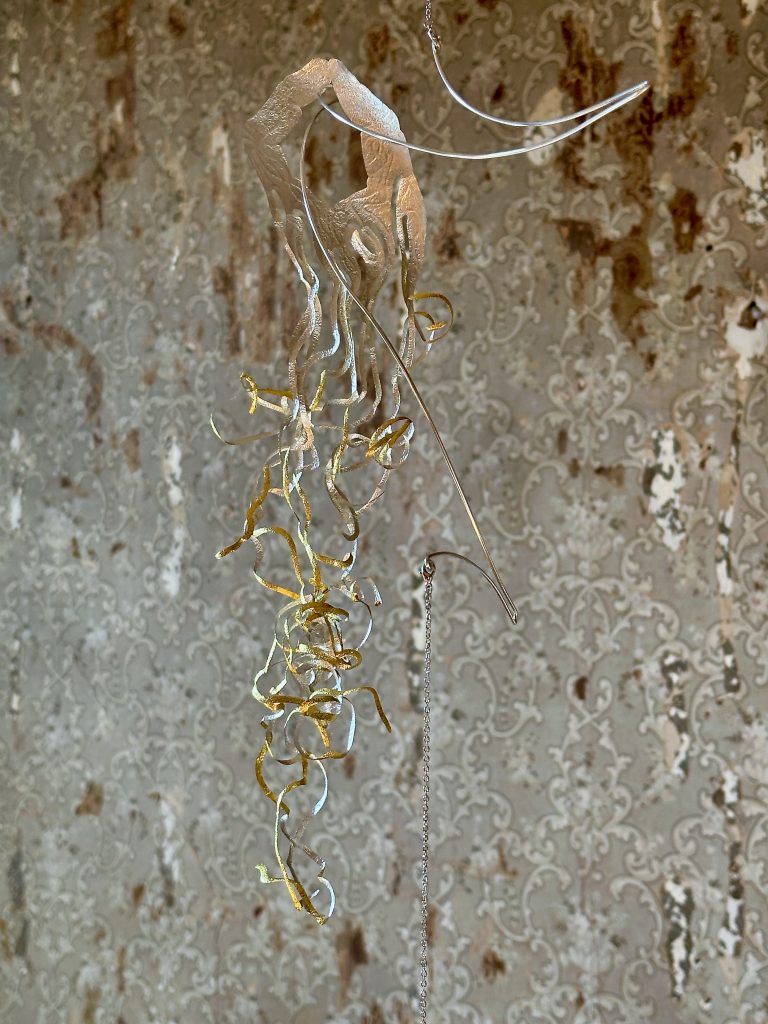

Blas Isasi opened his latest show, El viento will bring us home, at SHED Projects in Cleveland, Ohio, in early June. The show features a series of minimalist sculptures composed of metal, chain, and textured aluminum foil, set against the backdrop of SHED Projects’ historic landmark base of operations.

The show stems from a pivotal moment in 1533, when Europeans invaded ancient Peru and plundered over forty thousand pounds of Incan gold and silver. The precious metal artifacts were melted down and transformed into standard gold bars used for trade. In Isasi’s show, the spirit of all the stolen metal objects has paired with the cosmic force of the wind to travel on a journey towards home.

Isasi pushes beyond the transactional nature of repatriation and reparations. El viento depicts an ancient and material reckoning that will happen whether we humans are there to witness it or not. To witness the work of Blas Isasi is irresistible.

The light of the sun spilling in through the windows of SHED Projects refracts off the aluminum foil pieces as they rotate in the wake of your movement. If you stop to rest alongside the metallic pieces as they journey, you can feel the past glinting back at you, beckoning you to face it—face history, face the root harm, face the reckoning. The materials are finding resolve, repair, and a new relationship to the past—will we follow their lead?

In this conversation, Isasi and I cover the role of speculative storytelling and deep time in Isasi’s repair work, the limits of the repatriation of cultural objects, and the ways ancient Andean cosmology and epistemology influence his art practice. We touch on Isasi’s monumental Prospect 6 exhibition to learn more about the impact of a triennial on his artistic career and his ongoing desire for more opportunities for rigorous experimentation and play.

. . .

The following interview has been edited for clarity.

Kortney Morrow (KM): I thought we could start with where you’re at in this moment in your career. You just had this stellar show through Prospect 6, 1,001,532 CE. You’ve gotten rave reviews. I’m curious what it’s been like to get back into the studio and be creating after a triennial?

Blas Isasi (BI): It’s obvious that 1,001,532 CE has been by far my most ambitious project ever. I was pushing my own limits, learning how far I could push my own practice in conceptual terms and also physical and material terms. At the same time, a very important aspect of my practice is that I have to enjoy it. I have to have fun. I have to retain this capacity and ability to surprise myself. I don’t like working with a rigid blueprint. I like to experiment and improvise a bit. I really had a great time making my show for Prospect and I’m hungry for more opportunities like that.

I had to stop working on my art for a few months after Prospect, but then I got this fellowship at Wash U, and I had the chance to get back to making again. At first, it was kind of scary. Was this a one-hit wonder kind of situation, or is this actually a new chapter in my life and my practice as an artist? It took me a few weeks, but then after those few weeks, I was back in the game. I will have a solo show at the St. Louis Art Museum in February [2026]. I’ve been as ambitious as I can be. I’m taking the lessons that I learned from Prospect, and I’m taking it a little bit further…or sideways. I’m feeling more confident about being able to work on bigger and more ambitious kinds of projects.

In that process, I had this show at the SHED. I knew I wanted to experiment. I wanted to try a different approach to the same subject matter, but from a different angle. I was not sure what that would look like, but I knew one thing—I knew I wanted to work with aluminum foil. A very important part of my practice is establishing a relationship with a new material, exploring it, and getting to know it; getting to know each other, in fact. I believe that materials and objects have their own subjectivity, so it’s an exchange. It took me a while to understand the right approach to this project. SHED granted me the opportunity to be playful and whimsical and try different things that I probably wouldn’t have allowed myself to try in a bigger, more grandiose type of project.

“I was not sure what that would look like, but I knew one thing—I knew I wanted to work with aluminum foil. A very important part of my practice is establishing a relationship with a new material, exploring it, and getting to know it; getting to know each other, in fact.”

KM: I love SHED projects for that reason. They’re fostering this rigorous sense of play and experimentation. That experimentation shows up in your new show. Something I wanted to talk through was materiality—you’ve worked with everything from paper to foam to wood to metal. I wondered if you could talk a little bit about the history that sparked your interest in aluminum foil.

BI: What I loved about aluminum foil is its ability to shine. It’s so thin and forgiving as a material. I like making very detail-oriented work, but also very labor-intensive work. Extremely labor-intensive. It sets me in a meditative mindset. It allows me to connect with materiality in almost a spiritual way. I’m also very much aware of the fact that with this kind of labor intensiveness and detail-oriented work, I’m taking a risk of making something that is too precious. That preciousness leads to commodification and fetishization and whatnot. That’s what I want to avoid. And that’s why I normally choose materials that are very ephemeral or perishable or very fragile, because it counters that preciousness. That’s a very important poetic operation or gesture in my work that is a conceptual and spiritual engine. Why aluminum foil? It’s shiny, it’s flimsy. After the fact, I connected the dots, and I realized the silver and gold connect to the conquest of the Incan empire and Atahualpa’s ransom.

KM: You mentioned fragility, which is something I wanted to touch on. I find your work extremely poetic. As a poet, poetry is just as much about the words on the page as it is about the white space around the words. There’s a level of restraint to your work that I find incredibly intriguing. It allows the history that you’re grappling with to show up in a different way. There’s a stillness and openness to what you create that allows the viewer to re-see. I wanted to hear a little bit about the role of restraint in your work and in your process.

BI: My body has learned to do that. It happens very organically. My body and my eyes, they just tell me—okay, this is enough. That’s why you see a lot of little accents in my work of extremely detailed, very fragile, very complex, very colorful moments, and then a lot of space, blank space, silence, and stillness. As I get older, I become more aware of the tricks that I have under the sleeve. One of them is this. It activates meaning, space, and ideas in a way that refreshes the world and refreshes reality. It reveals and unveils things that are just hidden at open sight.

KM: Could you talk a little bit about the role of the speculative in your work? Your last show had an element of collapsing time, blending history with the future. Your work creates a new sense of time. What does the role of the speculative afford you in your creative process?

BI: I’m obsessed with non-Western understandings of the world or systems of beliefs, and these different ontologies and epistemologies. I’m obsessed with Andean epistemology. However, I have to be careful not to idealize and romanticize these alternative ways of understanding the world. I’m not in favor of or advocating for a nostalgic view of the past, like a lost paradise situation. There’s this radical shift of mindset that we need to do in the Western world. We need to break away from very linear and rigid ways of understanding how time works, how history works, and this very artificial nature/culture divide that is getting in the way of things. I’m trying to suggest this idea of the past as an actual future. Time is not this linear and progressive thing; it’s a circular thing that is very holistic. I want to use these other ways of understanding the world to try to imagine different ways of moving forward.

KM: When I was in SHED and looking at the pieces, the aluminum foil in “El viento” almost looks like it’s stopped or stuck or resting, and that it hasn’t fully completed its journey. It got me thinking about this larger topic of the repatriation of cultural objects. I thought, what would it look like if all of the Spanish accumulation of ancient Andean gold could be returned? But repatriation is rooted in a harm that you can’t entirely undo. You can’t undo the colonization that happened. I felt that your work was speaking to something more profound. There’s almost a reconciliation that is happening with the objects themselves, almost like they have their own memory. The landscape has its own memory. Could we talk a bit about the concept of reconciliation?

BI: Most people think in very transactional terms when thinking about reparations. There’s this idea that you can just write a check, and it’s going to be good. And of course, it’s not. My work is not about the actual material gold being repatriated to Peru. Peru is also a colonial country, a colonial project too, like the whole of Latin America. Do we, as the Republic of Peru, have the right to claim this heritage that belongs to an ancient culture that is alive, yes, but not in its original form? It’s a very complicated and problematic conversation if you set it in those very transactional terms. The idea is to go beyond that. This goes back to my talk about trying to acknowledge and see the world through these non-Western epistemologies and acknowledge the cosmic forces at play. That’s why you have el viento, the wind, in the title of the project. The wind is a cosmic force that originates in the sun, which activates all of these complex systems that make up the climate on this planet. We must acknowledge that reparations or reconciliation involves everything. Every single entity that exists on this planet, not only humans, but non-sentient, sentient beings, everything. The damage that was created by colonization and European imperialism cannot be undone, but we can return to a more holistic relationship with the rest of the entities with which we share this reality on this planet.

KM: There’s also this element to your work that’s saying—it’s not reconciliation, it’s not repatriation. It’s almost like a reckoning or a facing it, which will happen whether we’re here to see it or not.

You mentioned ancient cosmology and the sun. I know in past talks you’ve mentioned that installation for you is a playful part of your process. What was it like to install your work at SHED? It’s such a gorgeous space with so much life. How did the light and architecture inform the installation?

BI: I had so much fun installing this show. It reminded me of my P.6 project because I was working with a very complex space with its own history. It was like a negotiation of sorts. It was not just me posing my project in a very neutral white cube kind of situation. SHED is a very rich, complex space. I had to be very intentional, but also very intuitive, and apply some of those deep listening skills that I have been developing in the last few years towards materiality and space, and other than human and non-sentient things.

I had this great conversation with John while he was studying the work. I told him that the work is coming into existence right now, as we speak. I had the materials I had been working on for all this time, but they’re only coming to life right now. This is when and where the magic is happening. This is when and where the work is coming into existence. I always say that the install is one of my favorite moments because it’s like a playground, and the moment when I finally get to play with the toys that I’ve spent so much time making.

KM: I’m excited to keep visiting the space and seeing how at different times of the day, the light sort of shapes the work.

BI: The light is also a super important element, especially in a space that’s so complex as SHED. As the day progresses and the sun changes its position, the space changes radically. It’s almost like a different space in the morning than it is in the afternoon. Thinking about the shininess of aluminum foil, I knew I wanted to activate those intrinsic qualities of the material with light. It’s almost like a song in a way. Certain pieces are activated at certain times of day, and as the day progresses, other pieces are activated and others become silent. It’s almost like a musical piece of sorts, but a visual one. That also brings me back to ancient and Andean practices of using light to activate certain sacred places, certain sacred rock formations in the landscape. That was a very important practice that especially the Incans mastered. I want to bring some of that into my work. I hope to keep experimenting with that in the future. This project has been a very important learning lesson in that specific aspect of interest to me.

KM: I was listening to one of your past lectures, and you were speaking of the role that nature played in ancient Andean material culture. You spoke of the ways that architecture was informed by the natural forces. There was an understanding that natural forces would shape the things that they were creating. When we spoke at SHED, we talked a little bit about the role of gravity in the pieces in El viento. You seem so at peace with the tiny evolutions that will happen in the space over time because your work is in conversation with the earth, the climate, and natural forces such as gravity. Have you always had that understanding that the work will evolve and change, or did you have to arrive at that?

BI: I had to arrive at that. It took me a while. The first time that I dealt with this kind of situation was when my practice underwent its first major transformation. That’s like 10 or 11 years ago. I was at this year-long residency program in the Netherlands. I shifted from a very photorealistic kind of painting artistic practice to soft sculpture. I started working with paper. That’s the first time that I allowed myself to be super intuitive in the making of work. I was paper weaving in a very intuitive way. I wanted to be a kid again. The work grew and grew over days and weeks. I had no plan. I was just going with the flow, and I ended up with a very big piece that was kind of collapsing under its own weight. I had to come up with a solution for that. I came up with these cardboard structures that would support this growing entity of sorts. But then again, these cardboard structures would bend under the weight of the wheat paper pieces. The work was actively changing over time, and that was kind of out of my control. And that felt so liberating. But also, that’s the first time that I was like, okay, so the material has some agency in the creative process. It’s not just me. This is a conversation, this is a negotiation. There are some tense moments and there are some easier moments, but this is alive. In the past 10 years, I’ve been perfecting this ability to pay attention to materials under their ability to exert their agency, to allow it at times, and to sort of restrain it at other times. It’s almost like dancing, in a way.

KM: It does sound like dancing. It sounds like the deep listening that you’ve been able to practice allows you to know which way to go. SHED projects invited you to list some books that were inspiring you as you were creating the show. We talked about two of them, but we didn’t talk about one of them, which was a short story by Borges called “The Exactitude of Science.” That piece is satire that explores the futility of trying to document empire building and the tension between the documentation of place and the actual place. I wanted to hear from you how Borges has inspired you.

BI: You have to understand that he’s like a classic, especially in Latin America, you cannot avoid his presence. What I love about Borges is that it’s so obvious that he was having so much fun writing. He was so precise with the language, but to the extent that it becomes sort of absurd. I feel like he’s just been playing a joke, and people have been taking it seriously. On the Exactitude of Sciences has been the source of so many philosophical speculations, you know about Baudrillard and the simulacra theory. I don’t think that my inspiration from Borges has been straightforward and obvious; I just like his playfulness and his humor. That’s another aspect that I feel like is so, so important to an existential degree—and that’s humor. We need more humor in contemporary art. Sometimes it’s just too serious. I do play my personal jokes in my work, for sure.

KM: I’m wondering if, during the creation of this show, you had an aha moment or a moment in the studio where things just started to click. Could you describe that a little?

BI: I had plenty of those moments. The aluminum foil pieces came first. I started working on them last year, in my very rare moments of free time, but I had no idea how to present them or how to display them in a gallery space. I knew I wanted to activate these aluminum fold pieces with wind, but I didn’t know how. First, I thought about letting them be and just laying them down on the floor, opening the windows, and allowing the wind to do its thing. It was super poetic but not very practical. In the last three months or four months, I have been trying to figure out the way to incorporate the idea of activating these pieces with the wind, but with a device that is strong enough to hold them. It just came to me one night. What about hanging pieces? This is my first time making hanging pieces. I’ve always avoided that. At some point, I considered making a hanging piece for my P.6 project, and I decided not to. But I decided to try it this time. It just happened naturally. I just started to play with the materials. I had a ton of chains and these very thin and flexible aluminum sticks, rods, and I started to play with them and see where I could take this. I was just in my studio trying new things. I had this moment of, hey, I can hang these aluminum foil pieces. I had another eureka moment when I was just walking by the piece, and the piece just moved, and they became almost like motion detectors of sorts or ghosts. They were activated in a very vital way. I had plenty of those eureka moments, but it wasn’t until the final install that the full magic happened.

KM: You have a solo show in 2026 that you’ve been working on. I thought I’d give you space to share anything you would like about that show or where your creative energy is at right now in the studio.

BI: When I get too comfortable in a given material or technique, I kind of just leave it and let it go. I always try to incorporate something new. This time around, it’s bones. I’m carving animal bones and I’m fleshing them out with this modeling clay. It feels very exciting. My sand stones, which are these sun-coated sculptures, are evolving into new forms, shapes, and things that I find exciting. I’m also back into working with steel, but also looking at it in a different way. The new show at St. Louis Art Museum will be a distant cousin to my P.6 project; they’re related. This will be my first solo museum show. So far, it’s been a great journey.

KM: Anything you want to share or say that we haven’t covered?

BI: I just want to say that we need more spaces like SHED. It’s such a vital part of the art ecosystem. The work that Jon Gott and Gabrielle Banzhaf are doing is just amazing. We need more of that. Those are the spaces where the sparks come from, the sparks that set the fire.

. . .

El Viento Will Bring Us Home was a study in movement and memory, hand-formed in aluminum by Blas Isasi and presented at SHED Projects from June 7-July 19, 2025.

About the Author: Kortney Morrow is a poet and writer creating from her studio in Cleveland, Ohio. Her work has received support from 68to05, The Academy of American Poets, The Studio Museum in Harlem, Prairie Schooner, Tin House, and Transition Magazine. Her debut poetry collection, Run It Back, was the winner of the 2024 Saturnalia Books Poetry Prize, judged by Carmen Giménez and will be released in 2026. Kortney is represented by McKinnon Literary.