Tuning Away from Mechanized Listening features Midwest’s music ecosystems—listening cultures where thoughtful curation, collective engagement, and storytelling still shape what and how we hear. This series is meant to be a reminder: listening can be more than a passive, prescriptive experience.

Introducing Madeleine Aguilar and Jordan Knecht’s (un)learning Center

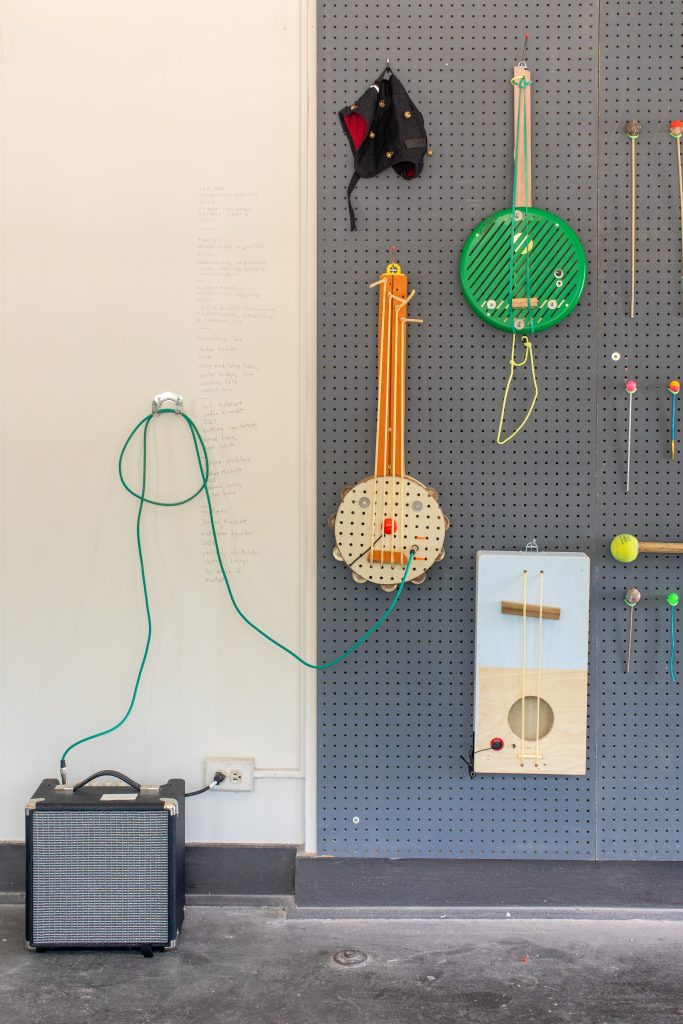

Located at Comfort Station in Chicago, the (un)learning Center is a collaborative exhibition by Madeleine Aguilar and Jordan Knecht, shaped through years of improvisation, responsiveness, and iterative creation. Featuring modular sound-making structures built both individually and together, the show encourages collective exploration. Visitors of all ages are invited to engage with these works where roles of artist, audience, and collaborator fade. Also included in the exhibition are books and garments available in a decentralized, trust-based store, with new works created specifically for this context.

The responses for this interview were gathered using voice-to-text transcription of a conversation that we had with each other in response to the questions. The responses were lightly edited for clarity. We worked simultaneously on a document in the same manner that we have written all of our proposals and copy for the exhibition being discussed.

Livy Snyder: When you arrive at the (un)learning Center, the first structures that greet you are wind chimes made with found objects that are installed on the front of Comfort Station. These were created by 10 artists and take a variety of shapes and forms, but of course, they’re all activated by the blowing wind. My eyes and ears are immediately drawn to the wind chime on the far left by Dionne Eskridge and David Sprecher. Made from chicken wire shaped like a birdcage with a piece of loose paper, it created a soft flapping sound, like the wings of a bird. These wind chimes set the tone for what’s inside: a space that invites collaboration, invention, improvisation, and play with sound. How did you arrive at this open, collaborative framework for making and listening? I think about the way you describe your process as a kind of intuitive parallel play—can you tell me more about this way of working together?

Jordan Knecht: I don’t think that I personally would have decided to invite everyone to do the wind chime element, but because you come from a lineage where every solo show also includes 20 people, it seemed very natural to follow that lead.

Madeleine Aguilar: I think that’s also very reflective of your practice. Everything you do is like “I’m inviting my friend to DJ with me” or “I am part of a collective performance”. You’re very much somebody who I recognize as a friend of many people. That spirit is very clear in your practice, because it’s just it’s never just you. It’s you plus all the people around you who are in your circle.

JK: I never thought of it like that before. I guess you’re right. I love that it’s something that we both do and both did before we even knew of each other.

MA: Yeah, it’s something we immediately recognized in each other, like “oh, you work this way too!”.

The thing I’m also thinking about in terms of our collaborative spirit, which is reflected in something that actually just happened right now while we were sitting here deciding how to answer these interview questions. I feel like every time I say “what if we did this?”, you are always like “yes, that’s a great idea!” I think that I do the same when you give me a suggestion.

JK: Mmhm!

MA: It’s that spirit of “yes, I trust you to make the decision that feels like it makes sense and you trust me to make the next decision.” We never really have to question where the power is or how the decisions are being made. We also work very fast in this way. We make decisions very quickly, so we’re able to work through ideas rapidly to get to the next one, which is why our collaboration is so generative. It’s more based in that I really do trust your aesthetic decisions. I also like the way you make things and put things together and create spaces and I feel like that feeling is mutual.

JK: Absolutely. The only “no” I experienced throughout our process was us about our own ideas. Then the other person would come in with a louder “YES”, dislodge the “no”, and we would keep going forward.

MA: Yes, that’s a really good point. We used that same system to invite other people into our space. In terms of like, “I know that you can make a beautiful chime, because I love your work and I trust you to take this prompt and handle it with care and make something beautiful with it.” Or with amateur H|O|U|R – “I trust you to be in this space of unknowing and be willing to feel uncomfortable playing on our sound structures for the first time in front of an audience.” I think that trust was very well received by all the people that we asked, because we intentionally asked friends who would be responsive to that calling.

[amateur H|O|U|R was an event of improvised music that the artists hosted in the exhibition featuring Andy Hall, Liz Flood, Chaz Prymek, Nick Turner, Oui Ennui, Mauricio López F, and ourselves.]

LS: There’s a quote from Aidan Seery and Éamonn Dunne in their book Pedagogies of Unlearning that came to mind when thinking about the experience: “A subsidiary sense of the verb ‘to learn’ refers specifically to an act of memory… Learning by heart is a wonderful phrase for acts of memory. The phrase compresses the notion of acquisition into a temporal vacuum. But it also spirals into questions of sense and sensibility. Does it mean that I understand or that I feel something? Does it mean both simultaneously? Or does it mean one or the other intermittently? If I learn a poem by heart, for instance, does it mean I acquire its meaning, that I can summarize it, or does it mean that I don’t know what it essentially means for others, only for me? After all, it’s my heart, right?”

This stood out to me because Seery and Dunne ask us to untangle and critically reflect on the process of learning—something the (un)Learning Center also seems to encourage, especially in relation to sound. What I took away was the possibility of imagining learning without a predetermined outcome, and of embracing joy, absurdity, and failure as serious tools for rethinking knowledge systems.

How do you see these elements—joy, absurdity, failure—shaping your approach to sound and knowledge-making? And how might they help us rethink what it means to learn by heart?

JK: I like the part where Livy is talking about using joy, absurdity, and failure as serious tools. Something that I see in both of us is that, even though what we’re doing is very playful, we do take it very seriously.

MA: I think that makes me think back to an early experience that I had with one of the first mobile music makers that I built at Compound Yellow. This group of jazz musicians had performed a set there and afterwards they saw the mobile music maker in the side gallery and asked if they could play it. We brought it out and I was showing them all of the elements. They were so into it and we were jamming for a while. It felt really powerful, that moment of somebody who’s discovering this object that I built for the first time, but who has a very trained understanding of music and is playing it in ways I couldn’t have played it myself.

After we played, one of the musicians was like, “oh, the harmonics in this thing & the way that this note is interacting with this note is so amazing. Did you arrange the instrument in this way so that these notes from the xylophone relate with these notes on the bells…?” I forget exactly how he worded it, but basically he was bringing up music theory as it related to the mobile music maker as if I had constructed it with that knowledge in mind. And I was like, “I know nothing about what you’re talking about, but I love that you see that!”

JK: [laughing heartily]

MA: It was that moment where I realized that there is such a beauty in not knowing, because somebody who knows the technical side could see something really profound, and somebody who doesn’t know could also approach the instrument intuitively because it feels inviting and easy to walk up to and start playing. And the fact that the mobile music maker could speak to such a range of people and such a range of skill sets is very reflective of that quote.

JK: Definitely, I love that story so much. Something that I think that we both do very well is nullify expertise or change the framing of what expertise is. It’s not this virtuosic singular individual pursuit that we’re after. It can be in relation to expertise, but we’re just not focused on that. It’s a focus on “how expanded can your mind be? How flexible can you be? How responsive can you be?” That’s what this work values.

MA: Totally. I think we made a bunch of silly decisions that felt almost like “we could probably secure this piece to this other piece in a way that makes more sense but wouldn’t it be so funny if it hangs off the end like this.” I think the “unfinished” nature or the “scrappy” nature of everything in the show allows for things to be so much more than just what they are. It allows the viewers’ or the participators’ imaginations to fill in the gaps.

JK: There’s so much where it could be seen as we’re being lazy or being silly, but to make things that don’t have explicit intention is also a really clear design decision where that scrappiness and openness creates a relationship which becomes collaborative with the object. It’s no longer just the object being acted with or upon, but it’s the object reciprocally acting on and with someone.

We’re also not just designing objects, obviously. We spent all this time in the space, designing the way people maneuver. We designed [a] system where things can move throughout the space on wheels to create new interactions—where object relations aren’t all fixed.

I think if success is this minute destination and failure is everything that is not that destination, failure seems like a much richer, more rewarding landscape to be in, because you have an infinite amount of options. Success is the… it’s like it feels like death…

MA: … of an idea…

JK: … and engaging with these open designs is embracing the failure, which is the constantly expanding landscape of potential and ideas.

MA: I also want to bring that back to queerness. That is queer design, in terms of creating objects that maybe don’t serve the intended purpose, but through use, the purpose is discovered as it applies to the individual. Like approaching each object in terms of “I create at the same time that I’m using.” That’s a really beautiful way to think about all the things that we made, in that we are inviting people to be creators at the same time that they are users.

JK: It saddens me, the way that people talk about queerness as this codified identity rather than speaking of it as this expansive potential for relations. I definitely think that our show is “queer design”, though. That’s a great way to put it. I love that there’s so many different words for it, but it’s exciting that it also inhabits the space where words aren’t necessary.

You can see when someone is prepared to enter into that mode of interaction and when they’re not. I’ve watched people walk in, touch a thing and be scared, because it didn’t do what they expected, and they walk right out. Then I saw people fall into a hole with an object and come out two hours later.

MA: Yeah, like when friends that we didn’t realize had a previous relationship with music entered the space and engaged with it with such joy and exuberance. The objects were fueling them at the same time that they were putting themselves into the objects. That’s a really beautiful part about making work that’s interactive. It’s like observing people in the different ways that they inhabit such a queer space.

JK: I think we also not only saw people that we didn’t know had musical inclination, but we saw people who personally didn’t know that they had musical inclination or had never been given permission to enact it. Two moments that really stuck out was Hai-Wen[-Lin] completely reinventing every single thing they touched, in a way that I could have never fathomed. And then also there was Nadia [John]. Every single time I’d come in, no matter when, they were on the turntables doing something completely possessed. It was great.

MA: I think of the fact that our opening and our closing was just like a 3 hour long jam session with everyone who entered the space.

JK: [laughing heartily]

MA: I think that’s a really beautiful representation of the show as a whole.

JK: Yeah, definitely [laughing] yeah

MA: We gotta put your hearty laugh in the answer of this question.

JK: [hearty laugh] “Hearty laugh.”

[both laughing heartily]

LS: Along similar lines, during my time at the (un)learning Center, I noticed how often people said “oops” or “sorry” when they made a loud or unexpected sound. I probably said it myself more than once. Did you notice this too? It reminded me how learning—especially when it’s unstructured—can feel disruptive, a little unsettling, even interruptive. How do you think about those moments of discomfort or messiness?

MA: I didn’t really hear “oops” or “sorry” very much. The moments that I did experience that feeling of “oh I did something wrong” in somebody was when somebody broke something. Usually what they were breaking were the mallets, which is funny because we had made so many of them with the idea that we would lose some over time. There would usually be a moment where I would see this look on their face, where they’re freaking out and look at me. This happened with a little kid one time. It happened actually with a friend, too. I would always feel like, “oh don’t worry they break all the time.” I was very conscious of trying to make them feel like, “it’s okay that you’re breaking one of our artworks in our show”, which is like a pretty big thing. It’s just expected with something being so interactive.

JK: Anytime I saw someone break something, I would look at them and start laughing. It was the funniest thing to me. I love that our show interrupts the expectation of what an exhibition is and how you interact with it…

MA: … because also we had a self-serve gift shop with books that I was selling through my press and clothing that you were selling through yours, and the idea of itself being self-serve was that we were trusting people to pay for it, but we’re also okay if they stole it. To have a show where it’s okay to steal and also break things is pretty radical.

JK: I was a little bummed that nobody stole anything. I was also a little bummed that nobody stole from the exhibition.

MA: I wasn’t. [laughing]

JK: The only person I know who walked away with the records was Nadia [John] who I told to take any records that they wanted.

I just gave a talk specifically about our show in relation to my teaching practice. I talked a lot about when you visited the first grade class I was working with. That, I feel like, is the exact environment that the show exists in. There were students who had to learn how to play or have to learn how to have fun, because they had no way to register whether or not they were doing something right. They were used to preparing for a test and then all of a sudden the only success was through alignment with themselves or alignment with their environment or their peers.

MA: That’s beautiful.

JK: There’s something I saw happen with adults plenty of times in our exhibition. People who were awful at jamming because they didn’t know how to listen. Which was okay, cuz they were also having a blast. It didn’t seem to stop anyone else from jamming or having a great time. It was just something I observed. It didn’t feel good or bad. It was that they hadn’t developed the skill of being in relation to other people with sound. They would do their thing and other people would either try to join along or just ignore them. I’m grateful that I actually didn’t see that much discomfort. The people who were discomforted just didn’t participate.

MA: Yeah, that reminds me of when Chris Reeves was visiting and I was sort of shadowing him around the space. Every time he’d pick up an instrument, I would go to another instrument and start playing alongside anything he was doing. At a certain point he was like, “Is this what you do? Just fall into a jam with anybody…”

JK: [laughing]

MA: “… or you can listen to anything that anybody is doing and you’re able to communicate with that?” I thought that that was such a funny question to ask, because I was like, “yes, exactly, that’s the point of this whole show!” That’s everything that me and you [Jordan] did. It’s listening deeply to one another and getting into some sort of jam, whether it be working on an instrument side by side and watching what the other person is doing. Whether it’s putting prompts out into the world to other people so that they can jam with our ideas. Whether it’s physically putting ourselves in uncomfortable situations like giving an artist talk with each other without any plan or knowledge of what the other person was showing. That’s exactly what we did—fall into a jam with everyone who entered this space, especially each other.

JK: Does that kind of jamming ever feel uncomfortable to you?

MA: I think it only feels uncomfortable when it seems like the other person is resistant or not willing to be in that space with you. When it feels like I’m forcing somebody to do something that they don’t want to do. That’s never a good feeling. But being responsive and being in an unknowing space I think always feels very exciting to me personally if all parties are down.

What about you?

JK: Yeah, I think if there’s a misalignment, that dissonance can feel disorienting, can feel stressful, but generally I feel like I’m at my best when I’m in a state of unknowing.

MA: Same.

JK: I feel like the space we created truly became the playground. Everything was happening and not everything was happening together, but nothing stopped anything else from happening. Sometimes that was pure chaos, like when you’re walking down the street and you see a playground of kids. It looks like mayhem, but it’s just a bunch of different things happening with no relation to each other.

MA: Not everybody has to be in alignment in order to have fun.

JK: Sometimes everyone was playing simultaneously and having fun. Sometimes everyone was listening to each other and having fun and it sounded really good. But it was always fun.

MA: Yeah.

JK: Hopefully if it wasn’t fun people just left. That’s the ideal.

LS: One of the most memorable details from the exhibition was a dying flower glued to a bouncy ball. It was such an unexpected combination—something that made me smile immediately—but it clearly made sense to the person who created it. It felt like a small but powerful example of the kind of vision and intuitive logic at work throughout the (un)learning Center. Can you share a moment, encounter, or performance—however small or surprising—that shifted how you think about the (Un)learning Center, your sound practice, or your way of being in the world?

JK: My friend Matt visited the exhibition with his daughter who is maybe 3 years old. More than anyone that I interacted with in the exhibition, she knew exactly what to do. I would show her that you could rub something and she would take a mallet and rub it on every surface she could find. With anything that she unlocked, she would try it in every variation that you could imagine. When they arrived, I was sitting there with my hot glue gun and my drill just drilling holes in things and shoving different sticks in them to make more mallets. She really wanted me to make the mallets that she wanted. I had been going out and taking garbage from the construction site and making mallets… drilling into rocks and things… and her dad was like, “oh yeah go get some sticks for some mallets.” The first stick she got was just a dandelion. I was super excited, so I drilled into the bouncy ball and shoved the dandelion into it. She was really stoked and I was really stoked and then over the course of the exhibition, the dandelion stem dried and became very sturdy. I had no clue what would happen, but it’s still intact. I also glued a dandelion on the top. The most fun I had in the show was hanging out with a three-year-old, because she understood the show in a deep intuitive way, more than any adult.

MA: And you collaborated with her too.

JK: She made so many decisions in the show which is really great. I really can’t take credit for that object.

I love using broken AI, especially voice-to-text transcription for the ways that it enters into non-syntactical space that humans can’t fathom, because we’re limited by our rules of language. Working with kids feels similar in that they’re unencumbered by all of these rules that they eventually become indoctrinated with. So [Matt’s daughter] was kinda like AI, just going through all the variables, where all variables had equal weight.

MA: Oh wow, yeah. She didn’t have any “no’s” yet.

JK: Except she likes flowers!

[both laughing]

MA: Yeah I was thinking about how after like three weeks of our show being up and I had gallery sat for a few days already. We’d had events where we would jam with people after performances or talks that we gave. I was thinking about how I felt so practiced at this intuitive responsiveness, because we were doing it so often with so many different people. That feeling was surprising, because it’s something that I think we both consider ourselves very good at—being responsive, being open to making sounds with somebody else. But the fact that all of the instruments existed in one space just opened up exponentially more possibility for sounds and collections of sounds to be made, versus one of the structures existing individually which is usually how I’m engaging with them or how we’re engaging with them together. I think that was such a special part to me about having a show with all of these objects in one space. That somebody can be across the room from you making a sound on an object and you can be communicating with that person from the opposite side of the room on another object that was made by another person at another period of time. It almost felt like time traveling. Or the condensing of time into one space.

JK: Yeah. Deep time.

MA: Deep time, yeah.

I think also jamming with my parents for the first time–

JK: That was the first time?

MA: It was! Jamming with both of them for the first time was really shocking, because I didn’t realize it was the first time until I was in the moment with them and I was like, “whoa I’ve never like jammed with my dad before” or, “oh, I’ve never jammed with my mom before”.

I had a moment during one of the events where I was jamming with my back turned and I heard somebody playing something really cool on Mobile Music Maker IV. I remember thinking, “oh that’s so good” and I was responding to it from across the room and really jamming to it. And I turn around to be like, “who is that?”. When I turn around, I realize it’s my mom!

JK: Wow. Oh that’s incredible.

MA: I think in working together with you, I was very surprised sometimes about how simple a solution was for a problem that felt really big. That happened pretty consistently. What we pulled off felt really big, especially while we were planning it and talking about it. It just felt like a lot of components and a lot of work. I think the thing that you brought up pretty often is that what both of us care about and stress about at different times is sometimes the opposite thing. That lent itself very well to what we ended up pulling off, because sometimes we needed somebody to make the quick and easy decision which actually made a lot more sense than the big and complex one. And sometimes we did need a more complex knot to hold something on the wall versus the quick & easy one. Those moments felt like we had picked the right person or we were heading in the right direction or it’s all going to come together in the end even if it feels insurmountable. I think that was the coolest part—in the end we pulled it off and it was more than we could have imagined.

JK: There’s this myth that I’ve had to unlearn—that in order for something to be worthwhile it has to be a challenge. I had to remind myself often throughout making this show that when things felt easy, it wasn’t because we weren’t doing a good job, it was because we were in alignment with what needed to be done. It felt like a very taoist practice, not in some predetermined way, but in that we always found the easiest way. Sometimes the easiest way was complicated or complex, because there was no other solution. But even when the way was complex, the complexity wasn’t hard.

MA: I think that was reflective in the way that we balanced the workload too. At times, it felt like one of us was carrying a lot of responsibility. And at other times, it felt like when one person actually needed a break and had other things to do, the other person started carrying that responsibility. By the end of the show, it felt like we were finally carrying equal responsibility at the same time. Whereas throughout the show that sort of ebbed and flowed as our availability did. I thought that was really cool how that worked out.

JK: Definitely.

MA: I don’t know how important that is to this interview, but it feels significant.

JK: I think it’s really important. I see all these people who are just killing themselves to do a thing. I just feel like it doesn’t have to be that way.

MA: Yeah, you do a thing and it brings you more life, hopefully.

JK: I think this might be the first show that I’ve finished where I didn’t get sick after it [laughs] in my entire life. I feel like I got reenergized every time I’d go into the space.

MA: I feel reenergized after this show in terms of what my work looks like at the end of this. It feels completely changed because I understand now the power in what we’re making and the importance of the spaces that we’re building. I think I felt a little lost in general with making for a little while. This show definitely feels like a helpful reminder of why it’s so important for it to exist in the world right now. And why it’s so necessary to create spaces for collective joy and collective exploration and collective unknowing.

JK: I don’t think I can say it better. Yeah, that’s great.

Madeleine Aguilar and Jordan Knecht’s (un)learning Center was on view at Comfort Station from May 4, 2025 – June 1, 2025.

Madeleine Aguilar is a multidisciplinary artist + musician from Chicago. her work is often mobile / modular / interactive and can be found in backyards, libraries, storefronts, homes, galleries & book fairs. @__bench_press

Jordan Knecht is an artist, educator, DJ, musician, and systems designer, surfing the wave of unknowing. @jordanknecht

About the author: Livy Onalee Snyder’s writing has appeared in the journal of Metal Music Studies, DARIA, Newcity, Ruckus, TiltWest, and more. She graduated with her Masters from the University of Chicago in 2021. Currently, she holds a position at punctum books and serves on the board of the International Society for Metal Music Studies. Listen to her live on WHPK 88.5 FM Chicago. Read more of Livy’s writing for Sixty here

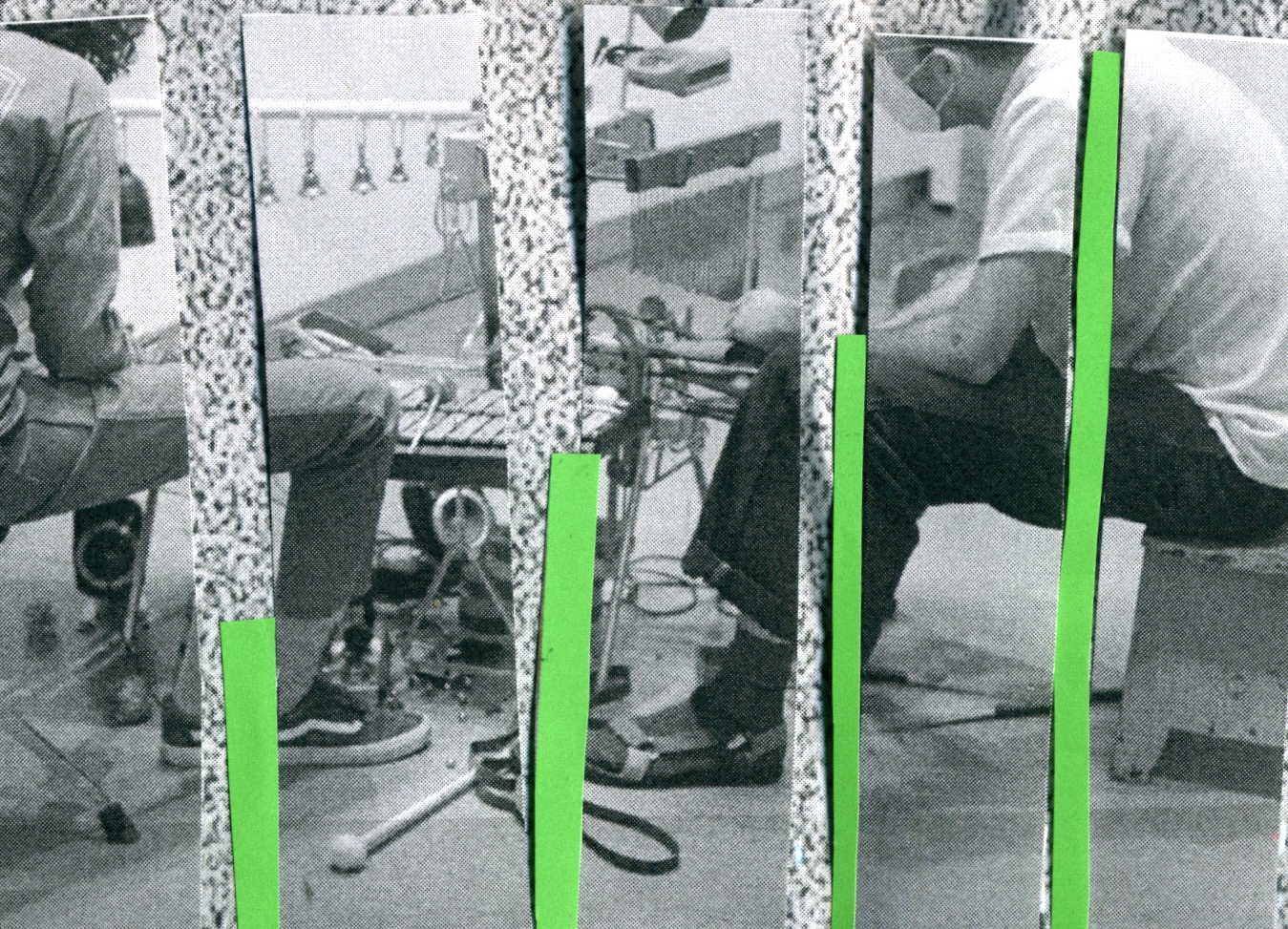

About the illustrator: Bri Robinson is a mixed media artist, analog collagist, sculpture artist, and historian who weaves intricate narratives of love, loss, and identity across the expansive Midwest. Through their unique process of cutting, pasting, and layering, Bri deepens the meaning of these found objects, transforming them into evocative works of art. Bri’s practice is deeply rooted in the exploration of identity, relationships, and the constant evolution of self. By merging archival materials with elements of popular culture, they create thought-provoking narratives that invite viewers to engage with the complexities of the queer experience. Through their work, Bri honors the past while also pushing the boundaries of contemporary art history, crafting pieces that are as introspective as they are expansive. Check out their work on instagram @niq.uor.