Time to admit an embarrassing truth: even though I play music on the radio—a role that suggests some kind of authority or expertise—I’m truly terrible at remembering the names of albums, artists, and songs. When someone asks what I’m currently listening to, I say, “I don’t remember, but their album art looks like”. Maybe it’s because I listen to so much music that it’s impossible to remember it all. But more likely, it has something to do with the listening infrastructure I’ve used and been submerged in for over a decade.

I don’t want frictionless and forgettable encounters with music and sound. I want messy, personal, weird listening experiences that sink in and that I can recall. So, lately, I’ve been trying to change my listening habits into a listening practice. To reorient and slow my attention, I keep a notebook. I jot down what I hear, take notes on music books I’m reading, paste in my favorite reviews from music magazines, sketch out concerts I attend, and log the tracks I play on my show. It’s not just about holding onto memory. It’s about resisting the way streaming platforms and the attention economy flatten the listening experience, and relearning how to listen with more care.

In 2013, a Spotify advertisement featured two young people sharing a pair of headphones, about to kiss. The tagline read: “Because mixtapes still work.”1 It was an early attempt by Spotify to frame their playlists as akin to the mixtapes of the past—handcrafted, intimate, and personal. But, as the author Liz Pelly argues about this example in Mood Machine: The Rise of Spotify and the Costs of the Perfect Playlist, despite Spotify’s claim to engender human connection, their model has shaped a passive, mechanized listening culture that pushes us further apart.

After being misled by these false promises, it’s time to disentangle ourselves from these omnipresent streaming platforms and the attention economy. I ask you to reinvest in alternative infrastructures for sonic connection. Exit the Spotify app and turn up the FM radio, talk to your local record store owner, follow a music substack, exchange messy mixtapes with a friend, go on a sound walk, purchase a music zine. Engage with sound infrastructures where your listening habits aren’t just data to be optimized or the AI DJ creates playlists riddled with ghost artists. If you’re already doing this, do it more.

Tuning Away from Mechanized Listening features Midwest’s music ecosystems—listening cultures where thoughtful curation, collective engagement, and storytelling still shape what and how we hear. This series is meant to be a reminder: listening can be more than a passive, forgetful experience.

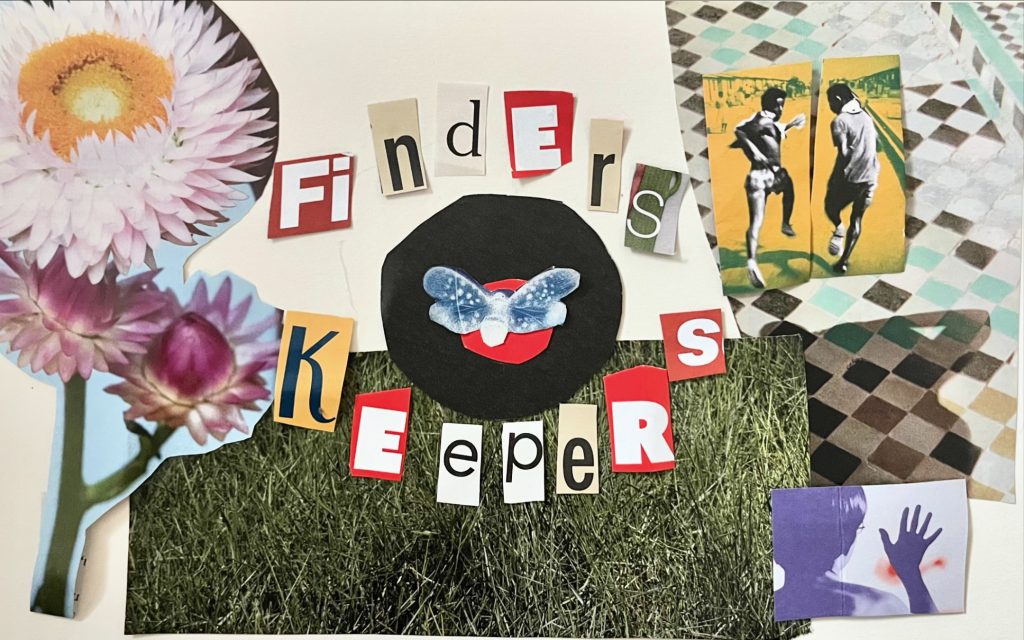

Introducing Finders Keepers

On Wednesday mornings at 11 am, WHPK 88.5 FM DJs Léa Sainz-Gootenberg and Rhea Madhogarhia host a variety of guests on their show, Finders Keepers. Guests select two or three songs to share over the course of an hour with personal stories and anecdotes. This year, Finders Keepers specifically featured DJs from WHPK to learn more about its community and history.

Livy Snyder: Tell me how you first came to WHPK and developed the show Finders Keepers.

Léa Sainz-Gootenberg: I started as a DJ at WHPK the fall of my first year of college and I would come in once a week, do my show or go into the station to plan it out, but it was definitely very solitary, and I only knew a couple of people at the station. Then, Rhea and I met in the summer of second year—we talk about this on the show a lot.

Rhea Madhogarhia: Yeah, Léa and I really got to know each other on a summer trip to New Orleans. Some of our mutual friends, like my roommate and some WHPK DJs, had already known each other and we went to New Orleans—obviously for the jazz—and we spent so much quality time together. And I was like, ‘oh my God, I’m so glad I’ve gotten to know this person.’

Also, I did web radio in high school and wanted to do radio at UChicago, but first year just wasn’t the time for me. At the beginning of second year, I approached Léa and asked “how can I get a show?” I wrote a proposal for a music talk show, and asked Léa if she wanted to be my cohost. And she said, sure. That was the birth of the show!

We started off Finders Keepers in my Snitchcock dorm room where we did a practice show.

LSG: It was just the two of us, and we listened to Arthur Russell, Planted A Thought. We talked about it for like forty-five minutes.

RM: It was honestly our best show and it’s nowhere, but we needed to know how it [the show] was going to work. And it worked. So, our first show [at the station] was just us, Léa brought Not by BigThief. Then we started bringing our friends and other DJs onto the show, asking them to bring some music. We decided not to listen to the songs beforehand.

LSG: It’s officially been over a year now.

RM: And I feel like we’ve just gotten more courageous with who we reach out to. We even invited someone Léa met at a Wicker Park cafe.

LSG: Yeah, I met this lady [Cindy] at a cafe, and she’s an artist and illustrator. She was talking to me and somehow we got on the topic of radio and I told her that I have a show on WHPK and she should come by.

RM: We also cold call. This summer we invited this writer, Peter C. Baker. He writes for the New Yorker. He’s also a novelist and has a Substack that’s very similar to our show, but in a written format and it’s not interview-based, so we decided we should have him on [Finders Keepers]—he’s based in Evanston. It was a crazy coincidence.

We also had Travis Jackson!

LS: I remember listening to that one! It was really good.

LSG: He was amazing. He’s such a good professor.

RM: And then we had DJ Erick Hampton. Erick was the start of our community DJ guests. We became friends with him and he would listen to our shows so we asked him to come on and we learned so much about the station. We realized we should talk to more community DJs because obviously they know more about the station and its history. I mean we just don’t know the history. I’ve only been here for a year. And, you know, we have our own little pocket of the station, but I didn’t know how WHPK runs.

Next, we had Track Master Scott. He’s so involved. We also had Taigo and we just had in Laurence. All of them brought a different perspective.

LSG: And I’m also learning about Chicago history, music history. WHPK was with so many of these people before they were DJs at the station. It was such an important part of their childhood. Everyone listened to it growing up, it’s amazing to see. They know so much.

RM: They’re so connected to it. WHPK eats, breathes, and lives through them. And why wouldn’t it? It’s an awesome community when you actually get to know it. We hear a bit of nostalgia about like, the rap battles and all that good stuff.

LS: I feel like everyone’s like, “oh, the rap battles put WHPK on the map!” And it’s definitely a highlight, but it’s one part of a long history with WHPK. Since its beginning, the station pushed to play every kind of music, it’s so free and experimental—that’s why the rap battles came naturally. WHPK wasn’t just open to new types of music, it was encouraged!

To your point about WHPK DJs growing up listening to the station and feeling nostalgic—it brings me to another question. For new listeners and DJs like yourselves, why radio now? Especially with so many options for streaming. For folks who didn’t grow up listening to WHPK, why are you drawn to it?

LSG: It’s a good question. When you have so many choices, being able to listen to anything on WHPK makes music even more special to us. I’m going to listen to music that’s curated and gives a slice of the DJ’s own personality and tells a story with their musical taste. Spotify DJ is just a meaningless droning of music.

Something special about WHPK is that every single week at the same time, you know there’s going to be a certain sound or that you’re going to find a song that you would have never found on your own, and maybe it isn’t even online. And I think that’s something that [way of discovery] is dying and it has to be preserved.

And it’s special that it isn’t just a community station. It’s not just a student station, but you have students and community DJs back to back. Every hour is so different and it never gets old.

LS: I really feel like it’s impossible to get that kind of scope you need to explore and experiment with your musical taste on your own—you just can’t. Sure, you can try to go on Spotify, but it’s biased and riddled with ghost artists and production companies. And what you said about the shared live listening, the human element, I think there’s a real appetite for that because we’re so isolated by technology and enclosed in our own echo chambers. When young new listeners discover WHPK it’s like oh, there’s something to this.

RM: Honestly, I know that DJs are supposed to be these elite curators of music, but I’m really not picky. One thing I’ve been doing this year is whenever I go home to Los Angeles, I don’t really listen to my own music. I find myslef only listening to radio. Whether it’s KISS FM (102.7 FM) or KJazz (88.1 FM) I just scroll through the channels until I find something good for the moment.

The reason is because I just want to know what people are picking—that’s the sole thing I care about. And that’s also the spirit of our show. It’s not about how good the music is. It’s about why they picked it and how it informed their taste. What draws them to a song? When you can just turn on the radio and flip to any station and there’s a person behind that choice, that’s inherently pretty special to me. And maybe that makes me lax with my taste, but I see radio as getting to know a person.

For WHPK specifically, it’s not like other university stations because of the amount of community DJs we have. And we have people playing Taylor Swift, you have people playing jazz, you have people playing metal, you have people playing everything. But the station is not defined by the music, it’s defined by the people who play it.

LS: It’s true. It’s always a gamble with what you’re going to hear and I am always curious to know more about the person who picked it! I think to myself, I have to know more about this person.

RM: At first, I was super scared of joining WHPK because I didn’t have that musical background, but listening to WHPK made it easier to join because I realized I could play anything. And the appreciation of the DJs for all types of music, especially the hip hop tracks that have been played on our show, you can tell that their musical influences are so wide. It is soul. It is Jazz. It is R&B. It is pop. It is rock. Like, Taigo loves everything.

LSG: We started with one song for every show and now we’ve switched to two or three songs so people have the option to show the little slices of what they listen to. I feel like that gives us a wider range.

And things have changed a little bit in the sense that we used to ask really, music-specific questions. And now it’s a lot more about the person and the memories that they have with that song and it’s more of a story.

RM: We wanted to give them the chance to talk about their musical journey more on the macro rather than with the micro specific questions, because people process music differently. The word that comes to mind for WHPK is amalgamation. It’s everything.

LS: Did you grow up listening to the radio a lot?

LSG: No, not very much. I mean, I was obviously a little bit of pop radio, and my parents were chronically NPR people but that’s not the same as community radio. My dad really likes records. So we’d go to a lot of record shops. And so growing up around physical media made me want to join the radio station in college. But I think it’s become so much more than that.

RM: As kitschy as it is, I only listened to radio growing up. My parents don’t know anything about music. They’re immigrants and when I ask them what songs they listened to in high school, they can’t name a thing. So when we were driving to school, it would only be radio, and it was like KISS FM (102.7) billboard top one hundred and Disney (1110. AM). But I was listening to Ryan Seacrest do his Ryan’s Roses thing, and him and Kelly interact on the air and, in addition to music, I loved listening to people talk—it was radio, and it was all I listened to. So yeah. Radio was important.

LSG: It’s fun to think about who’s listening. Part of the fun is that we have no idea where the people are, and the people who are listening don’t know what they’re going to get.

LS: It’s interesting to think about geography in relation to the history of radio, because before the internet, the geographical scope of the broadcast was limited. With WHPK, for instance, the broadcast only reaches the South Side of Chicago without the internet. Now it’s much different because we have access to the broadcast in so many different ways. The community has expanded. Now, when I travel, I can tune in to hear my favorite DJs. Or my folks can tune in to hear me during my show even though they’re several states away. I think a lot about who the WHPK community is; who has access. I see a lot of potential in that. I also wonder if you could talk about the challenges?

LSG: What the community DJs are talking about is how the neighborhood is literally unrecognizable. These songs [that guest DJs choose] take them back to a time in Hyde Park and Woodlawn when they were growing up and there’s always a subtext. There is definitely a strange dynamic between the community DJs and the student DJs. It’s not something that can be easily resolved, but it’s genuinely a reason I like having people come together, having people, hang out more and bond over the one reason why we’re all here, which is just sharing music with people.

I mean, [when we get together] we talk about that love for sharing music and keeping the station alive. The university is giving the radio station less and less money, like they’re defunding any arts club, any arts program. But I like hearing the history of the station and the importance of it for the neighborhood. So like hip hop and jazz [history] there is more widely available information and I think even just by having a community share their music in their own way. The fact that there are DJs who have been here forever. Like Marta Nicholas has been here since the 60s. That’s impressive.

RM: Getting any DJ to talk about the past, is super informative, not only for us, but also, there’s no other way, or at least an easy avenue that’s publicly available for people, to share it [history of the community and station]. There’s some writing, books and stuff, but there’s a financial barrier, radio is quickly accessible to the community.

So that’s also been a push for myself. I’m not just going to the studio when it’s our show. I go and get my recordings at a random time during the week so that I can see who’s on. Or I’m going to play the station on my pocket radio so that next time I go to the station at that time, I know the DJs name.

It’s hard to build a new community unless you realize what the old one was, because you’ve got to respect what they already have. And obviously we don’t want to recreate what they had. That’s not a realistic expectation, but to make a new community that works for both the community DJs and the student DJs. For student DJs, you’ve got to understand where they’re [community DJs] coming from.

LSG: I mean, you just have to listen. Like to listen—it’s literally that simple. It does feel strange to me that WHPK is student-run. Like of course, that’s how it functions and like how the school gives us funding. But when I look at us like we’re essentially teenagers we’re trying to run the station and they’re [community DJs] saying wait, we can totally help you. We just have to listen to community DJs.

LS: Agreed! Knowledge sharing is super important between community and student DJs. It’s how the station survives.

I also wanted to point out that physical space like the Hyde Park and Woodlawn neighborhoods, will always change, but the frequency of WHPK remains the same. So that’s something we can hold on to. And that’s why we have to maintain that sonic space, because that airwave like it’s going to remain open for the community despite everything else. Physical space will change, but you tune into that frequency 88.5 FM and WHPK is always going to be there.

LSG: I also love the ritual with the call sign. 88.5 FM Chicago, Pride of the South Side. Like you have to say it. It’s my favorite part. If you’re a first-year student and it’s your first time on air or if you’ve been here for 40 years, it’s the same ritual that you say 88.5 FM Chicago every time.

Finders, Keepers – WED 11:00-12:00 https://whpk.org/show_info/?showid=97

Public Affairs – DJ: Finders, Keepers with Léa & Rhea

Finders, Keepers is a public affairs interview show on WHPK. Each week, hosts Léa and Rhea invite a different guest to share a song on air with them, and spend the next hour unraveling the musical complexity of the piece while encouraging their guests to share the threads of memory attached to their song. Previous guests have included close friends but also strangers, who encourage them to explore new and unheard music, memories and ideas.

Footnotes

- See the full add here: Paul Sloan, Spotify tries to go mainstream, launches splashy ad campaign,” CNET March 25, 2013. Referenced in Liz Pelly’s Mood Machines. ↩︎

About the author: Livy Onalee Snyder’s writing has appeared in the journal of Metal Music Studies, DARIA, Newcity, Ruckus, TiltWest, and more. She graduated with her Masters from the University of Chicago in 2021. Currently, she holds a position at punctum books and serves on the board of the International Society for Metal Music Studies. Listen to her live on WHPK 88.5 FM Chicago. Read more of Livy’s writing for Sixty here.

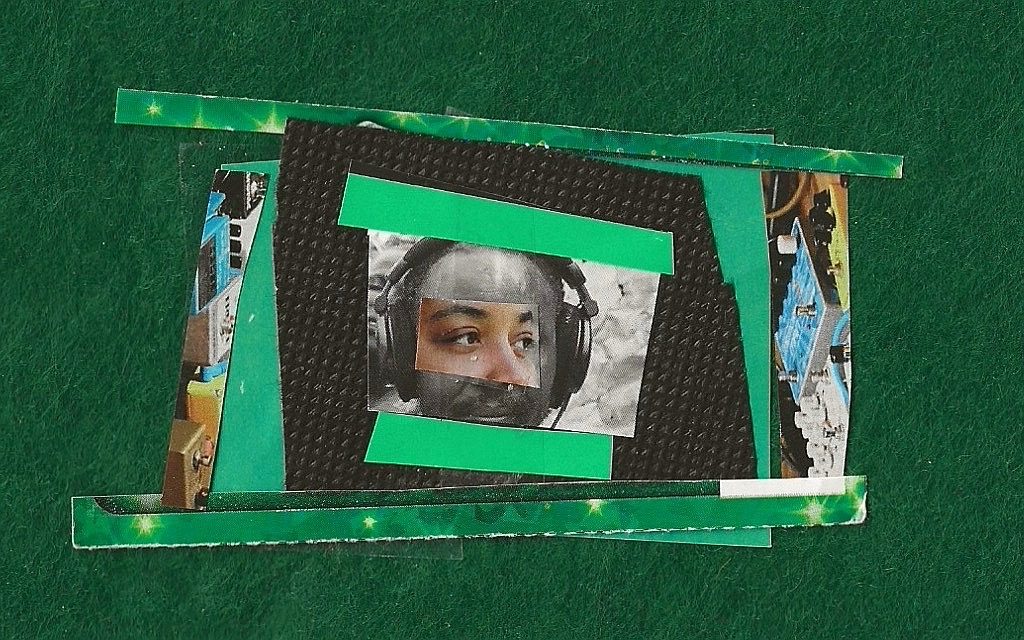

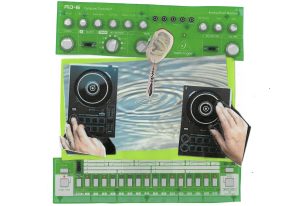

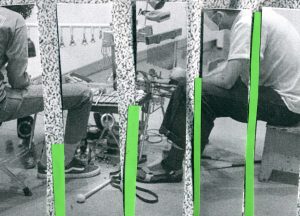

About the illustrator: Bri Robinson is a mixed media artist, analog collagist, sculpture artist, and historian who weaves intricate narratives of love, loss, and identity across the expansive Midwest. Raised in Ohio and now based in Chicago, Bri’s work reflects the rich cultural tapestry of the region, combining personal history with broader societal concepts. Brought up by a large, close-knit family, Bri draws inspiration from the everyday moments and memories that shape our lives, using images found in family photo albums, adult magazines, and personal portraits. Through their unique process of cutting, pasting, and layering, Bri deepens the meaning of these found objects, transforming them into evocative works of art. Bri’s practice is deeply rooted in the exploration of identity, relationships, and the constant evolution of self. By merging archival materials with elements of popular culture, they create thought-provoking narratives that invite viewers to engage with the complexities of the queer experience. Through their work, Bri honors the past while also pushing the boundaries of contemporary art history, crafting pieces that are as introspective as they are expansive. Check out their work on instagram @niq.uor.