Tuning Away from Mechanized Listening features Midwest’s music ecosystems—listening cultures where thoughtful curation, collective engagement, and storytelling still shape what and how we hear. This series is meant to be a reminder: listening can be more than a passive, prescriptive experience.

Introducing Allen Moore’s Sound Walk Hear Below

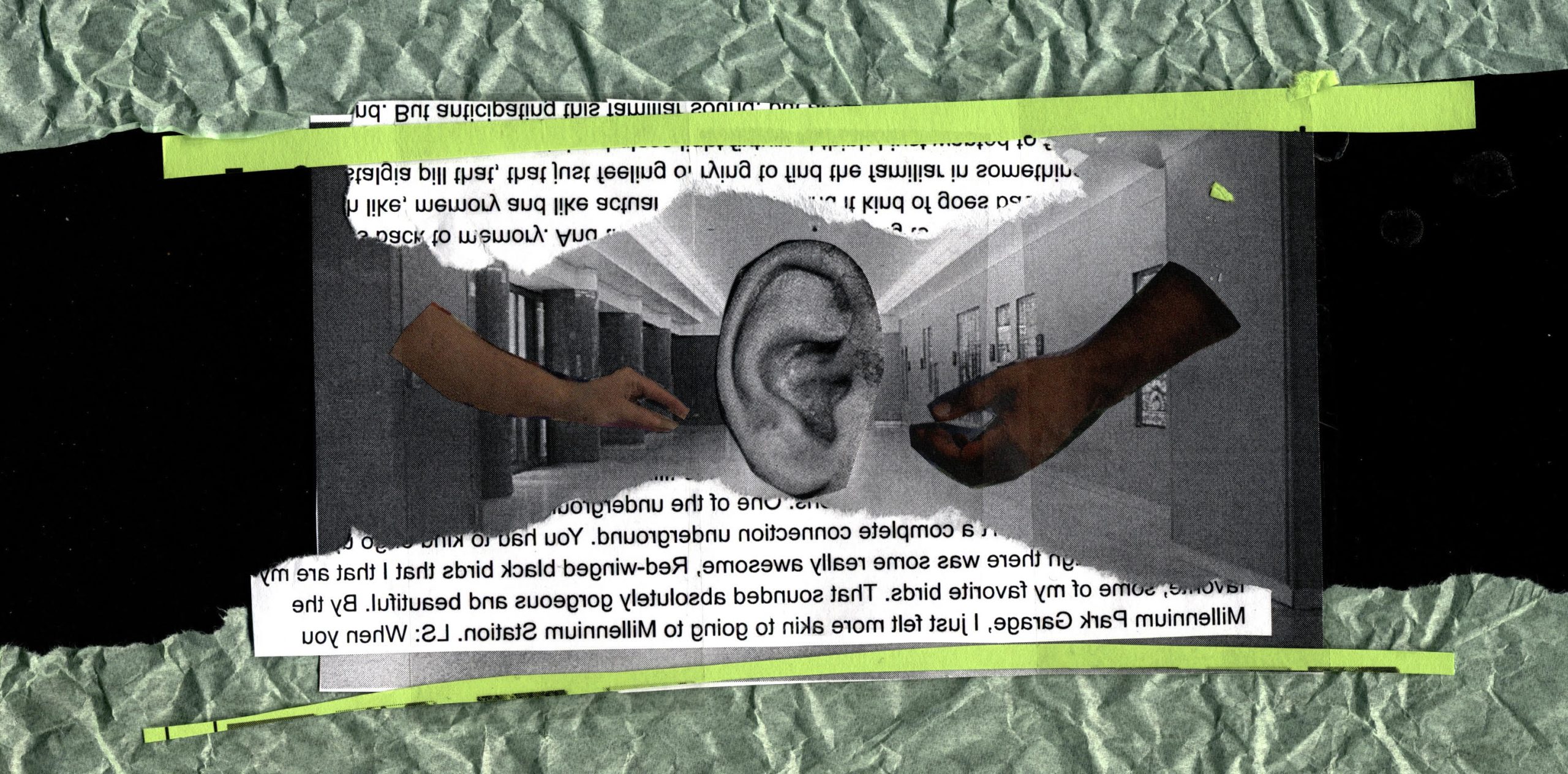

People gather at the Block 37 mall, downstairs, and across from the elevators. We’re directed to look for the sound artist Allen Moore, dressed in a yellow skull cap, blue backpack, grey sweatshirt, and black Adidas pants. Eventually, a small group forms with the intention of walking through and listening to Chicago’s Pedway System. We introduce ourselves with the songs from the radio’s top one hundred blasting in the background. We slowly move towards the sliding glass doors. As they create a swoosh sound, the loud music of the mall fades into the background, and we emerge in the busy entryway of the redline station. The group disperses around the space to explore every creak, bang, ding, bell, tick, and hum. The attendant takes notice of the crowd. As we explain that we’re on a sound walk, she shares her own observation about the bustling area: It’s noisy, and it never stops. After a while, we move on through the long halls and pass multicolored stained glass window displays that are installed next to Macy’s under Wabash Ave. We listen closely to see if the lights behind the stained glass buzz, we meditate to the white noise of the air filter, and shuffle our footsteps to figure out the sound effects of the textured floor.

Along the quieter parts of the hall, I feel very aware of my keys clipped on my jeans, jangling with every step. Does this sound interfere with the sounds that normally occur in the environment? I alter my pace so the keys don’t sound as loud. Down the hall, a couple of baseball fans are shouting, but they quickly shift to a whisper as they pass our listening group. A woman talking on the phone eyes us and speaks to the person on the other end of the line, “hold on, something’s going on here.” More people alter their sound as they pass us. Try as we might, we aren’t quiet, anonymous observers in the soundscape: We are part of it.

Eventually, we turn the corner of the long hallway into Millennium Station: music, bar sounds, footsteps, train whistles, conductors and passengers shouting, loudspeakers repeating announcements over and over. We gather to hear a final train whistle before making our way outside, beneath bridges and roads. With the rumble of cars and footsteps overhead, the sound walk comes to a close—but the group keeps listening.

Livy Snyder: I had the opportunity to participate in your sound walk through Chicago’s pedway system, and I think I can speak for all the participants when I say it was a truly special experience. Everyone walked away feeling joy and gratitude to you for bringing it all together! Speaking of which—how did the project come together? What was the process like? And what ultimately led you to choose the pedway system? Were there other locations you considered?

Allen Moore: This project started with Christophe [Preissing], for NON:op. We worked on a few different projects in the past actually. Though I had not led a sound walk for Hear Below, I did recordings for the project through the pedway. This was pre-pandemic. I also really felt compelled to do a sound walk at this particular time. I have a real nostalgic appreciation for Millennium Station and for the different areas of sound. When I was still in college, an undergrad, I was working downtown, and taking the train from my hometown, Robbins, to downtown Chicago, to the Illinois Center. And I got introduced to the pedway that way. It saved me trouble and it saved me a lot of time going into work.

I found that Millennium Station was really important to me, because that was the station that I would take, you know, going, coming, all the time. It’s one of the places that I would always go. My entire life, my family, we would take that train whenever we would go downtown to the Taste of Chicago or any kind of Chicago event, museums, things like that. We didn’t go super often, but the Taste Chicago was one of the venues that, like, my mom really, really enjoyed because she was a really great cook. Millennium Station always held a special place in my heart. And I was there before they renovated it, and I remembered how it was.

And then I remember how it was, the sounds of the train, the sounds of bells overlapping, like calls for which train is leaving where, always just charged me with the feeling of home in a way. I love the hum of the trains. I love it. Everything just seems so cinematic to me. I really appreciate a lot of the Chicago subway/pedway system, but I have to say that Millennium Station and the South Shore line holds a lot of intrigue for me because I just really appreciate the idea of us being these passengers, huddled in one station but going to different places and us having completely different origins. And so as singular as our everyday movements in our lives can be like in and just monochromatic and in my, like, as I try to illustrate these emotions to think about somebody else coming from someplace totally different, having the, the same or just a different life but the same kind of like routine that you have.

It really just made me think a lot about connection, a lot about where we all come from. So, looking at those trains, really watching them kind of leave the station, it’s hard to explain, but there’s just a lot of wonderment, if that’s the right word for it. And just joy, and intrigue because the sounds, you know, are important to me. Like, sounds have been important for me my entire life. Sounds create, like, an entire bodily experience. You know, I feel it, I taste it, I smell it. it’s a very dominant sensory experience for me.

And, I have to say, I really appreciated the whistle of those trains. I really did like some of the smaller areas where we got to hear the clicking/dripping of the air conditioning through the vents. I had previously considered the Millennium Parking Garage, and I considered being closer to the Illinois Center, but part way I found that there weren’t a lot of connections. It wasn’t a complete connection/path underground. You had to kind of go up. Even though there was some really awesome, Red-winged black birds, which are some of my favorite birds, I didn’t want us to have to go outside until the very end. I just felt more akin to going to Millennium Station.

LS: When you recall the sounds of the pedway system, what sounds stand out the most in your memory? And I’m curious, now that you’ve led a sound walk through the pedway system with a group of people, how did that memory of the sound differ from the experience itself?

AM: There was a lot more sound than I realized as a commuter. It was easier to discover with a group of deep listeners than you can, I think, alone.

At least that’s how I felt. And I felt nothing but gratitude, to be honest with you about that, because the way we decide to listen isn’t going to always be the same each day. I think it’s going to be different, depending on your mood, depending on your environment.

And so the environment itself doesn’t change. It’s the people that change. So having different people, having an awesome group that we had together, I think it made me slow down even more because I realized that I move a lot faster when I’m listening at the same time as watching. I’m moving, at a consistent pace, but really having to slow down and do deep listening with a group of people really made it that much more enriched.

And there were so many more layers to it.

LS: I find the expectation of sound to be a very revealing aspect of sound walks. For instance, when you and I were putting our ears next to the American Victorian stained glass windows in the Chicago Pedway to see if the light behind the glass would make a sound. We expected there might be a noise from the light itself based on our visual senses. There probably was a faint buzz, but it was drowned out by the music emanating from Macy’s across the hall. I’m wondering if you could share a little more about your thoughts on expectations and sound.

AM: Well, I think and if I don’t get too philosophical here, I think that we can definitely look at something and have this feeling. I think it triggers memory in a way, when we see something we want to hear something, we see something we want to smell, taste, touch with all senses.

Our brain can fill in the gaps and can kind of make up things that we think we are going to experience. And I do specifically remember looking at those stained glass panels and feeling like I could hear a hum. That to me was just a connection to a hum that I heard from my past growing up.

So it always goes back to memory. And that expectation is just trying to fill that gap and conjure connection with an actual experience. And it kind of goes back more to that, like a nostalgia pill that just feels like trying to find the familiarity in something, even as small and distant as a stained glass light fixture. I think I just wanted to find a familiar sound. Anticipating a sound but being okay that we couldn’t hear “what we wanted”. I still feel like there was something there. And again,. I know I’m repeating myself, but just, it really just makes me feel kind of that feeling of nostalgia, you know, those memories, those sensations, those feelings back in the day, you know, from some completely separate experiences. We’re just trying to find or connect them like constellations. Actually, I cheated and pressed the elevator button very early in the sound walk. I too felt the impulse to want to, like, make sound. I couldn’t help it.

I am an experimental musician, so I absolutely love making improvised sounds. And just letting that sound be on it’s own, whatever it needs to be. Looking back, pressing the elevator button was a bit comical, especially when you’re trying to be quiet and listen to natural sounds. We were as much a part of that environment as we affected the sound in that space. We affected other people’s curiosity, even though we didn’t realize we would elicit that response..

We became part of the environment. A lot of people started to slow down with us, and I found that to be interesting. I don’t know if I would have done the same walking past a group of people standing still, unless I felt like there was something bad that was going to happen.

But I thought that was really just an awesome interaction. Just us affecting the space and being affected by the space at the same time. I don’t think that we get to be as passive as we think that we all are. We mistakenly think we are observers that are not to be seen. But I think our curiosity is always going to make us lean in and listen more than we want to admit, therefore, we are part of something bigger. Even if you’re looking out the window at someone in the distance, you know, You’re kind of creating this connection. Someone or something is always watching. There’s a squirrel that’s probably watched me more than I’ve watched the sunset in my backyard. You know what I mean? There’s just a lot of observation and watching what happens. And yes, whether you want to or not, you are participating in observations that are bigger than just you. So I believe.

LS: I was doomscrolling on Instagram the other day when I came across a quote from a Dazed article that said: “Why are some young people ‘quitting’ music? In a world of constant noise and algorithmic influence, stepping away from music isn’t about rejecting the art form itself but resisting the passive, often compulsive habits surrounding it… The point isn’t necessarily to abandon music, but to relearn how to listen—with intention and the understanding that silence can be just as meaningful.” These quotes stood out to me because they echo a similar observation I’ve had. The intention of this series is to think more deeply about the sounds we consume—musical or not (whatever that distinction might mean). As a sound artist, what advice do you have for listeners—young, old, and in between? What practices or philosophies guide the way you listen?

AM: I truly believe there is no such thing as silence.

I think silence is a choice. And in the context of, you know, speaking up, or speaking against something. But as far as nature itself, there’s no such thing as silence. And I think I’ve got that from Nick Cave, but I think [that] for me, when I’m playing noise shows, I’m delighted at how many young people tune in and find improv or music intriguing. I know that when I was way younger, I was still listening to a lot of radio music, a lot of the prescribed rhythmic music.

I think that if you are a young person and you’re already tired of what you are hearing in mainstream media, and you are willing to step away and do deep listening, you are fucking awesome. How they tell us to do things and you know, how we’re being led, kind of like lulled to sleep by capitalism, we’re not deep listening enough. We’re not watching deeply, intently. We’re just kind of moving through. I just think that everyone needs to really take some time and find what it is you want to hear.

Apart from the mainstream media, I grew up watching a lot of TV. And I realize even now how much that shaped my opinions and my thoughts. You realize, like, how deep it can go into you and it can control or, like, make you conform to society or whatever people think that you should do. To break away from that, you need to put yourself in natural situations and in places that you don’t necessarily go. I’m not saying put yourself in danger, but exposing yourself, culturing yourself. Sound is just one avenue. Why should we not use our imagination? Or why should we be hesitant to do so? What we’re feeling when we’re doom scrolling isn’t all that’s out there. I don’t think that we have to prescribe that.

And I do really find it refreshing that people are moving away from it and finding relief in nature and natural things, I get it. And I don’t want to make the distinction between young and old, but I get it being older, meaning that, like, now the things that I took for granted and walked past them. I now slow down for the trees, the grass, the sunsets, they all mean something. Because now I know that they are not as limitless as I once thought they were when I was younger, and mortality is here. We have a beautiful world. And I just think that we need to take more time to really listen to it, see it, feel it. I think listening to that will guide us in a better direction than what we hear or see, because I feel like even now, especially with AI and how we’ve used social media, it’s curated in a way that we don’t have full control. We don’t have as much as we think.

LS: When’s your next sound walk?

AM: So my next sound walk is going to be in Palmer Square in Logan Square. And we’re going to walk around the park, and we’re going to really take some time and do some really nice deep listening. It’s roughly about a quarter mile around the park. There are some great sculptures. That’s going to be for the Midwest Society for Acoustic Ecology on June 15th.

* * *

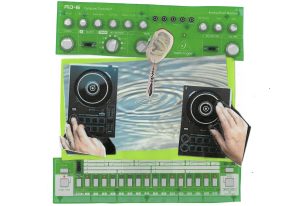

Allen Moore (he/him/his) is a Black Interdisciplinary Visual Artist, Experimental Turntableist, Sound Artist, Educator and Youth Mentor born and raised in the Historic Village of Robbins, IL. His conceptual premise is to analyze the signifiers of Blackness through performative Improvisation and experimentation.

Footnotes

1. See the full add here: Paul Sloan, Spotify tries to go mainstream, launches splashy ad campaign,” CNET March 25, 2013. Referenced in Liz Pelly’s Mood Machines. 2. Non:op Arts and Humanities is a Chicago-based non-profit organization that creates experimental art experiences by and for all Chicagoans. Read more about the organization here: https://nonopera.org/

About the author: Livy Onalee Snyder’s writing has appeared in the Journal for Metal Music Studies, DARIA, Ruckus, TiltWest, Signal, and more. She graduated with her Masters from the University of Chicago in 2021. Currently, she holds a position at punctum books and serves on the board of the International Society for Metal Music Studies. Listen to her live on WHPK 88.5 FM Chicago. Read more of Livy’s writing for Sixty here.

About the illustrator: Bri Robinson is a mixed media artist, analog collagist, sculpture artist, and historian who weaves intricate narratives of love, loss, and identity across the expansive Midwest. Bri draws inspiration from the everyday moments and memories that shape our lives, using images found in family photo albums, adult magazines, and personal portraits. Through their unique process of cutting, pasting, and layering, Bri deepens the meaning of these found objects, transforming them into evocative works of art. Bri’s practice is deeply rooted in the exploration of identity, relationships, and the constant evolution of self. By merging archival materials with elements of popular culture, they create thought-provoking narratives that invite viewers to engage with the complexities of the queer experience. Through their work, Bri honors the past while also pushing the boundaries of contemporary art history, crafting pieces that are as introspective as they are expansive. Check out their work on instagram @niq.uor.