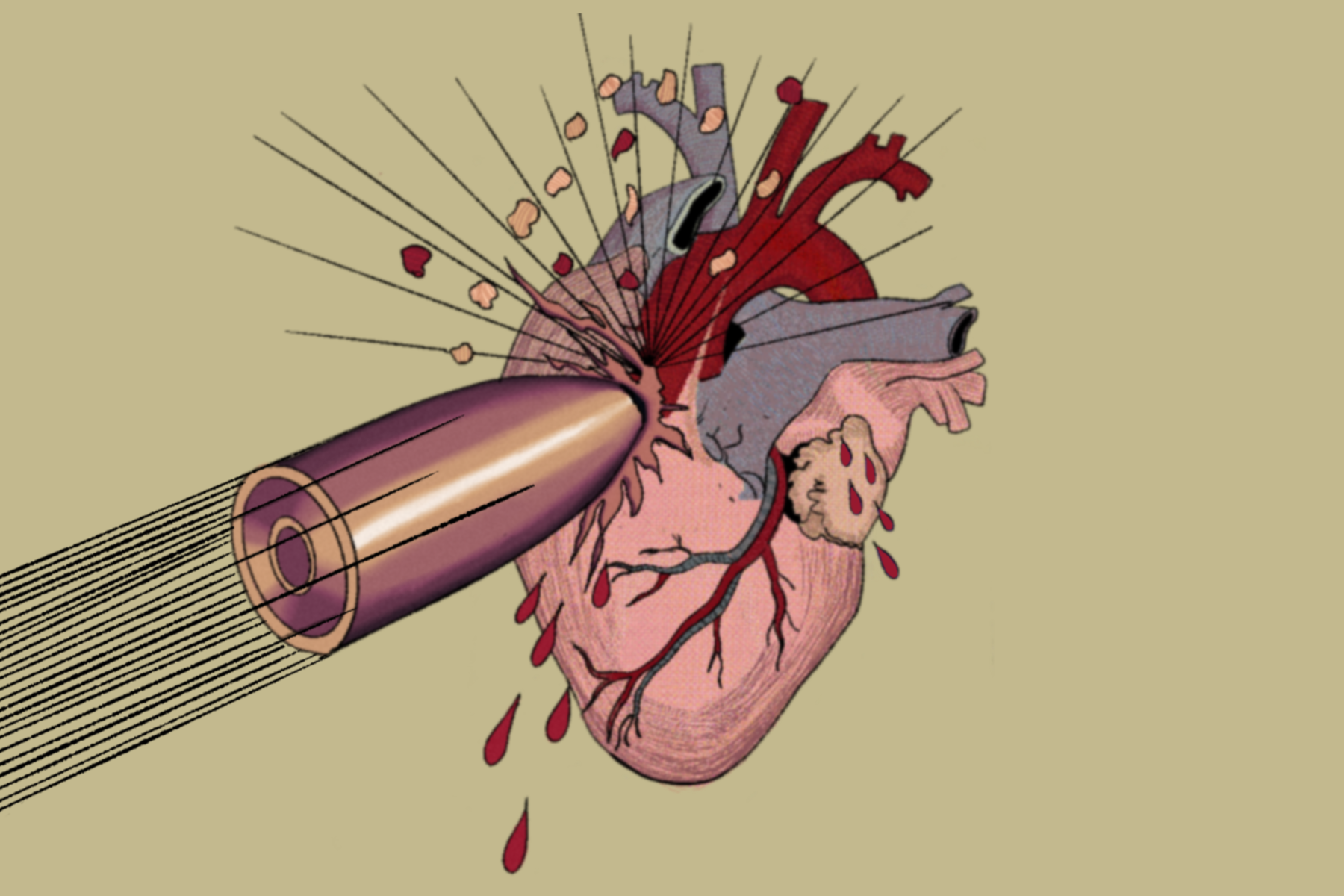

There is a dime-sized hole in my chest. Its edges are jagged and pink, and it smells like an overused, souring dish rag. If I crane my neck far enough, I can see the circular face of the bullet where it buried itself in the damp, burgundy muscle of my heart. Despite my exhaustive attempts to pinpoint the exact moment I was struck, I don’t remember being shot. I know I’ve carried the bullet since I was a child, rarely mentioning it to anyone. I naively believed my injury was unique, that I shouldn’t speak about it to anyone in order to avoid becoming defined by it — afraid that others might only see my wound. I was unnerved to discover that strangers had nearly identical wounds and was even more stunned to realize that they were also able to recall and describe early memories where they became aware of the projectiles nestled between their ribs. The Spanish writer Paul B. Preciado recounted a similar experience, “I was three years old when I felt the weight of the bullet for the first time. I knew I was carrying it when I heard my father call two girls walking hand-in-hand in the street ‘disgusting, dirty dykes.’”

I was 15 years old when I felt the weight of the bullet for the hundredth time. I was riding in the backseat of my father’s Jeep Wrangler. My father was driving, and my uncle was sitting in the passenger seat. We were on our way to the office of the automotive robot repair business they started together. I cleaned the office bathroom once a week for some money. It was the day before my 16th birthday, and I was trying to decide between having my parents take me to Outback Steakhouse or Red Robin for my birthday dinner. Fox News was playing on the radio. The host criticized President Obama, who had reversed course and announced he supported same-sex marriage in the face of re-election. The host condemned the move, insisting that marriage is a union between a man and woman. My uncle scoffed and said, “I think we should send all the gays and lesbians to a remote island. The men are all effeminate, and the women are masculine, so they would be a perfect match for one another. That or natural selection will run its course and they’ll all die.” He enunciated each word so forcefully that droplets of spit flew from his mouth and landed on the dashboard like campfire ash slowly drifting to the ground. I stared out the window, nervous that my uncle might catch my eye in the rearview mirror and accuse me directly.

I worried that he might somehow know how often I fantasized about being a girl, the hours I spent in my room wrapping my bedsheets and tying them in a tight knot around my chest, walking back and forth with a gentle sway in my hips, pretending to be Drew Barrymore as Dylan Sanders in Charlie’s Angels when she volunteers to spend the night with Eric Knox — a software genius played by Sam Rockwell — under the guise of guarding him from his kidnappers. The two have sex and Dylan emerges from his bedroom swaddled in a sheet. Eric confronts Dylan and reveals that his kidnapping was a ruse designed to hoodwink her and the other two angels before he shoots her. The bullet narrowly misses Dylan. She tumbles backwards, saved by the bedsheet snagging on a shard of broken glass, which allows her to fall, roll down the hillside, and land roughly in a stranger’s backyard. Dylan uses cleverly placed pool floats to hide her naked body before knocking on the back door to ask for help from two teenage boys — who offer their ill-fitting clothes and miniature scooter.

I fantasized about that scene many times, although my fantasies weren’t the pornographic daydreams of a teenage boy who also wishes a naked Drew Barrymore might appear at their door in the middle of the night and beg for help. When I wrapped myself in my cotton sheets, I cast myself as Barrymore. I tried to imagine what it felt like to be flushed with pleasure after sex, giddily following after your lover without feeling the need to conceal your nakedness. I wanted to know what it felt like to be a woman who is desired, who might be the object of some teenage boy’s fantasy.

My uncle mimicked the stereotypical, high-pitched vocal fry of a gay man, which didn’t sound much different than my voice at the time; I was always being mistaken for my mother on the phone, even by her own sister — a fact that both excited me and made me feel ashamed. He caught my eye in the rearview mirror and grinned at me. The bullet felt enormous, as if it had expanded, swelling until the rounded edges of the shell pressed against the insides of my rib cage. The pain was unbearable. I felt as though the bullet might sprout like a seed, the shoot splitting me open like a slab of concrete that lost its long war against nature. Yet, I managed to ignore it. I paved over the fractures, convinced that I could feel nothing if I persuaded myself that the wound was childish curiosity, a fun game that I would lose interest in as I matured. This wasn’t the first time I decided to feel nothing, and it wouldn’t be the last.

I felt nothing when my brother told me that my mother asked if I was transgender after she saw photos of me performing at my university’s drag show in a limp, blonde bob wig, comically overapplied eye makeup, and a red satin minidress I thrifted and occasionally wore about my apartment. Like a passive aggressive teenager trying to be subversive, I posted the photos to my Facebook knowing my mother would see them. I laughed about it on the phone with my brother and insisted that I wasn’t trans. But, when I hung up, I felt uneasy, like after telling a harmless white lie that I know will unravel and embarrass me; I couldn’t help but wonder, why does it always feel like other people are able to recognize and name my identity before I can?

I felt nothing the frigid March night my first boyfriend, who I had been dating for three months, told me that he didn’t like when I wore heels or feminine clothes after we got home from a poetry reading at Women and Children First bookstore. He suggested that identifying as non-binary was a phase that I would grow out of. He insisted that he was gay and therefore only attracted to men. When I asked what that meant for our relationship, he said “We’ll just have to see.” He kissed me goodnight in the doorway of my studio apartment and told me that he loved me for the first time. After he left, I waited until I heard him reach the bottom of the stairs to quietly lock the door. I broke up with him the next day, subconsciously knowing that, despite all the hours he spent admiring my body, he had not seen the bullet hole, could not smell it festering with a sickly-sweet scent like a cheap cake from the supermarket, could not feel the sweltering heat radiating from the inflamed wound like an old steam radiator.

I felt nothing the time a man I had been dating for a few months walked me home from dinner and, while we were standing and flirting outside my apartment, he groped me and said, “Just wanted to make sure that you didn’t cut it off since the last time I saw you.” I drily replied, “Not yet.” He continued to talk, but I felt like I had lost any ability to understand language at that moment. I deflected his suggestion that we could hang out in my apartment for a bit and told him that I had to be up early the next day. He begrudgingly ordered an Uber and asked, “Do I at least get a kiss before I go?” I gave him a quick peck on the lips and stepped inside. I swiftly locked the door behind me. Later that night, I stood in the bathroom and tucked my genitals between my legs, squeezing my thighs together to give the illusion that I had a neat, triangular vagina. I squinted, stared at my naked body with my semi-blurred vision, laid my hand over my groin, and forcefully pressed until I felt one of my testicles retract into my groin. My legs started to tremble. A notification lit up my phone. It was the groper. He wrote, “I had a nice time tonight. Wish you were here in bed with me.” I separated my thighs and watched my dick hang dispiritedly between my legs before snatching my phone off the edge of the sink and blocking him on every platform.

Feeling nothing became unbearable. I instinctively followed every trans person that came up on my social media feeds. I googled “best trans books,” made a list of all the titles from an Oprah Daily article titled “12 of the Best Books by Trans Authors That You Need to Read,” and bought copies of each. I started idly researching hormone replacement therapy. But then I started dating a boy and became infatuated, so I made a bargain and convinced myself that I should wait to see how the relationship developed before deciding whether to medically transition because I believed that revealing my desire to transform my body would cause him to break up with me. Except he ended things anyway, making me realize how juvenile and asinine these rationalizations had been. After we said goodbye, I walked to the liquor store and bought a bottle of wine, which I quickly downed before curling up in a fetal position on my bed and watching the hour-long special episode of Euphoria centered around Jules Vaughn, a trans teenager played by Hunter Schafer. Jules makes a confession to her therapist: “I feel like I’ve framed my entire womanhood around men… I just, like, look at myself and I’m like how the fuck did I spend my entire life building this. Like, my body and my personality and, like, my soul around what I think men desire? It’s just embarrassing. I feel like a fraud.”

I cried deep, body-seizing cries. She was describing a feeling that I couldn’t shake; I also felt like I had framed my entire personhood around what I thought men desire. Admitting that I wanted to transition was unthinkable because I had decided that being desirable to men was the most important thing in my life and that, if I wasn’t desirable, I would be nothing. I knew how to date cis gay men, that older men liked my pubescent, boyish body, my flat stomach, my angular jawline, my peach fuzz-like facial hair. But none of my relationships lasted longer than a few months. I eventually began to feel like I was putting on a performance, playing a fictionalized version of myself I thought they would find attractive. Unsurprisingly, I felt like my partners didn’t understand me and balked at the idea of sharing that I frequently fantasized about having breasts, wearing dresses in public to somewhere other than the gay club, growing out my hair — so I sabotaged my relationships in other ways to avoid potential rejection if I revealed I might be trans. Despite all the years I spent obsessively observing women, I realized I didn’t know how to be desirable as a woman and that frightened me more than anything because who would I be if I wasn’t desirable? But I might never have an answer to that question. I had to surrender to the unknown.

I needed to transition. Or at least try.

I played that Euphoria episode two more times and then paced around my bedroom. I caught sight of myself in my mirror and scanned my body from head to toe for the first time in nearly two decades. I let my gaze linger on my wound, its shiny mauve edges, and I looked straight down the tunnel the bullet bore through my chest and saw a world I had seen nothing of before reflected in the mirrored face of the cartridge. I looked straight at my wound and saw myself taking my estradiol pills for the first time in a park while my friend films me. “I hope these make my ass fat,” I joked and tipped my head back, dropping the two oblong, baby-blue pills into my mouth, and washed them down with a swig of prosecco.

I saw myself being apprehended by a friendly but slightly misguided airport worker, who insisted I was mistakenly going into the men’s restroom and politely pointed out the women’s restroom, the first time I can recall passing as a woman. I saw myself at a gay go-go bar in New Orleans where one of the dancers offered to give me a massage. He slid his hands underneath the skirt of my minidress and pressed his thumbs against my lumbar and whispered in my ear, “Are you wearing lotion? Your skin feels like velvet.” I was dangerously tipsy at this point in the night, but I managed to have the common sense not to tell him “It’s because of the estrogen.”

I saw my great aunts calling me beautiful at my brother’s wedding while I was wearing a sage green turtleneck dress, a pair of black heeled mules, and a flower crown made of baby’s breath. I saw myself in my parents’ kitchen, zesting so many limes and washing dishes under scalding water for so long that my hands cracked and bled along the furrows of my finger joints the next day. Except, the minor wounds felt like a badge of honor — proof that I had adopted the domestic role of the daughter by feeding and cleaning up after my family. I saw myself slowly walking along Lake Michigan, trying to modulate my breathing as I prepared to call my parents after I sent a brief text to both of them asking if they were both free to talk. I explained that I was on hormone replacement therapy, and reassured my mother that there were no scary side effects — besides blood clots, which I could easily combat by taking an aspirin every so often. My mother replied, “I’m on hormones, too, although mine is for menopause.” I laughed and asked her if it was estrogen or progesterone, surprised she made the connection that we were both undergoing HRT without me drawing attention to it. As they prepared to say goodbye, my mother added, “I hope you know how much we love you.”

While I look straight at my wound, I see an afternoon from my childhood. My friend and I are play acting husband and wife in the basement — he is the husband, and I am the wife. I can’t remember how we decided who would be the man and who would be the woman, whether he claimed the clip-on tie first and I meekly acquiesced, or if I volunteered eagerly to be his wife. I pretend to cook and serve him a meal of plastic spaghetti, corn, and apple juice.

I dote on him, asking if everything tastes okay while he assures me it is perfect. I wear my mother’s pair of aquamarine pumps she set aside so my siblings and I could play dress up. They are ostentatious relics of the 80’s eye-straining style. When I slide my tiny, eight-year-old feet into the shoes, the heel of my foot barely extends beyond the toe, but I manage to follow my friend up the carpeted stairs. He complements the clip-on tie with a bowler hat. We peer down the hallway, trying to figure out if either of my parents are in the kitchen, and giggle, nervous at the idea of being seen in our costumes while secretly hoping my parents might notice and praise us for imitating their dull, domestic adult lives. We can hear my mother loading dishes into the dishwasher — the water turning on and off and the clink of plates accidentally grazing another. We wait for her to finish and walk our way, but several minutes pass and she doesn’t walk our way, so we prod each other and work up the courage to stand in the entryway of the kitchen without saying anything.

My mother laughs and yells for my father to grab his camera. We pose and my father takes a picture. This might be the moment I am struck by the bullet, but it’s an easy memory to confuse. A camera’s blinding flash is so similar to the incensed muzzle flash of a gun that’s just been fired.

Afterwards, we return to the basement, put one of my mom’s old dresses on the slightly damp concrete floor and lay on top of it. We don’t say anything. Our playful demeanor has faded, replaced by a stony seriousness. He leans in so close I can feel the wetness of his breath on my lips. I don’t move. He kisses me, a curt, uninspired kiss, like politely waving at someone you’d prefer to leave unacknowledged. But he kisses me again, a softer, eager kiss, this time like brushing your arm against an attractive stranger in a large crowd, hoping they’ll notice you. He raises his hand and pretends to fondle my breasts as we had seen actors do in the R-rated movies we sneakily watched from the second-floor balcony while my parents thought we were asleep. I realize a truth about myself at that moment: I want real breasts so I can feel the rush of his hands, any man’s hands really, brush across my nipples again, to feel like a swatch of upholstery fabric being stroked and caressed and admired — waiting to hear them exclaim, “You’re so soft and velvety. I would run my hands over you forever.”

My friend stares at me with his brown calf-like eyes and whispers, “You’re beautiful. I love you.” That was the day the red-hot bullet pierced my heart.

Acknowledgement:

Two years ago, during a very odd lunch, Fred Eychaner gave me a copy of Paul B. Preciado’s “An Apartment on Venus.” I shelved the book without reading it and finally cracked it open on a whim recently and finished it in a single afternoon. While I think he gifted it to me with a different idea of what I might learn from Preciado, the book led me somewhere else entirely and inspired this essay, so I owe my gratitude to Fred for this small act of generosity.

Riley J. Yaxley is a writer whose tenderhearted work evokes memories in order to contemplate the self and the ways we make sense of the world and our place in it. Their writing broaches topics such as motherhood and trans maternity; gender, sexuality, and desire; and the imperial history of philanthropy in the US. Riley’s work has appeared in Sixty Inches from Center, Chicago Gallery News, ADF Web Magazine and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago’s journal of arts administration & policy. The middle child of seven, Riley was born and raised in a Detroit suburb and currently lives in Chicago on the traditional unceded homelands of the Council of Three Fires. They earned their BA and MA in Writing, Rhetoric and Discourse from DePaul University.