“All I ask for is peace…”

I almost didn’t hear the words because they were delivered like a deep sigh into the exhibition space. As the line was being digitally exhaled into the room, three generations of Hazels rounded the corner of the main gallery to see the other half of Making Our Space: Members of the Peoria Guild of Black Artists, an exhibition curated by Jessica Bingham at University Galleries at Illinois State University. The show brings together the work and words of Kevin J. Bradford, Krystopher Dudley Brown, Alexa Cary, Kameron Hoover, David L. Jennings, Chantell Marlow, Alexander Martin, Erick Minnis, Morgan Mullen, Hannah Offut, Brenda Pagan, Rose de Peoria, Kayla Thomas, and Quinton Thomas–all early and founding members of the group lovingly known as PGOBA.

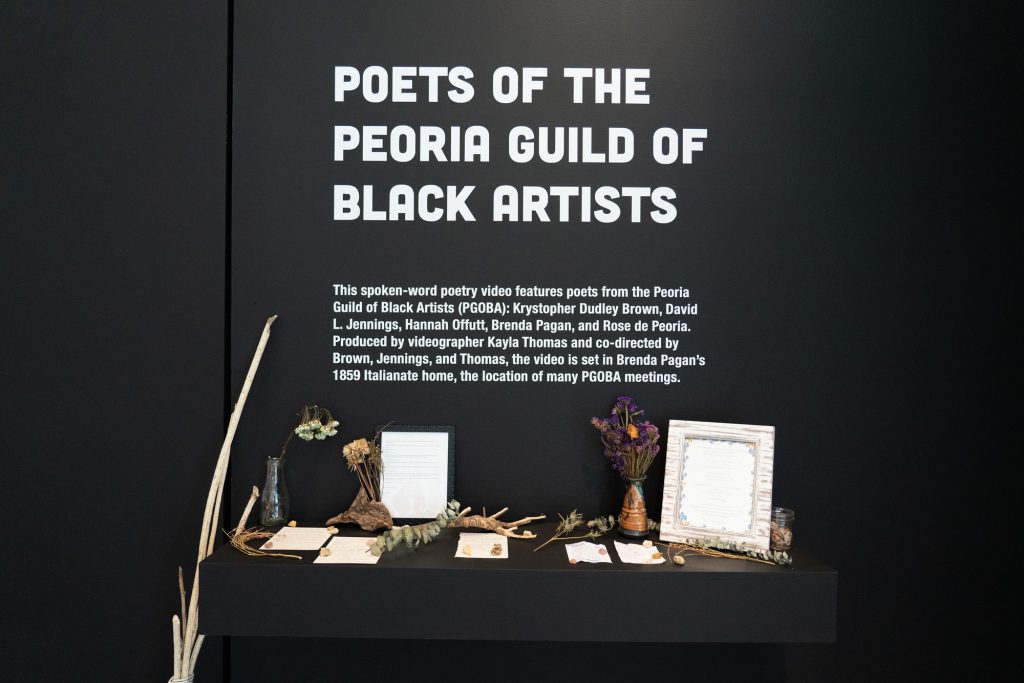

In between time spent with each piece and while on converging and diverging paths with my mother and niece, I was trying to catch and kept missing the source of the sigh. Finally, the three of us came together at an installation and video that was set up as a kind of rest area and centerpiece where a seat, a small end table with books and dried flowers, and a live plant stretching out next to a golden bird statue all faced a monitor on a free-standing wall that was painted black.

We listened to each of the poems, the last in the group being the piece “Young” by Krystopher Dudley Brown–the source of the sigh–which came with a series of quietly spoken but potent lines that I had to close my eyes to hear. On the wall adjacent to the video was a shelf that held an altar of poetry on paper, dried flora, rocks, and vessels. Among the materials was “Open for a Reason,” a framed poem by David Jennings (a.k.a. Anonymous Rain). Planted within his poetry was a line that forced a pause from me:

“A finite bit of any gift received can be enough.”

These words got me thinking. Spending Juneteenth in this space with two people I love comprehensively and in the company of the subtle and resounding work of the Peoria Guild of Black Artists (PGOBA) was a gift. Watching my mother take on the role of interpreter for her favorite pieces and seeing my niece silently spinning a mental and visual response to the work she was experiencing was a gift. But, too, I was reminded of the gift I received about one month prior when I spent time with Alexander Martin (they/them), Erick Minnis (he/him), and Brenda Pagan (she/they) at the East Bluff Community Center in Peoria, Illinois. What was supposed to be one hour of questions turned into three, and in that time they each gave me new reasons to fall back in love with the city I was born and raised in. That was a gift.

It’s often the poets who literally and metaphorically bring me home. Making Our Space reminded me of this truth.

The following longread is part of Testimony, a series of essays, interviews, and first-person accounts of the interior lives and exterior experiences of Black trans, Black women and girls, Black femme, and Black non-binary artists and friends. It is an edited version of my interview with Alexander, Erick, and Brenda where we discuss life, death, rejecting the masterwork, and world-building–a conversation that I hope never ends.

* * * *

Tempestt Hazel: Let’s begin with introductions. How would you introduce yourself and your practice to someone who doesn’t know you?

Erick Minnis: My name is Erick Minnis. I’m still trying to navigate what type of artist I am. I would say I’m mostly an experimental artist. I like to dive into different types of mediums. I often stick with the same themes, which are existentialism and the Black struggle. I’m a deep lover of existentialism–I love questioning the purpose of life and why or how we navigate it daily.

Brenda Pagan: I’m Brenda Pagan and I am a painter, sculptor, writer, and photographer. I work with plants, arrange things, and I document in any way that I can. I do portraiture and I like to paint big when I can. I’ve done some murals and work in arts education.

Alexander Martin: I’m Alexander Martin. I’m an artist, performer, and I make work about the intersections of my identity–being Black, trans, nonbinary. My work takes shape in collages, paintings, and mixed media work, but also through performance, ritual, and drag.

TH: I want to start by asking you all a pretty basic and potentially cliché question: When did you decide that art was the thing you wanted to do?

EM: For me it was back in 2013. I’m a huge anti-capitalist and I hate working for corporations. [At the time], at both of my jobs at K-mart and Goodwill workers were underappreciated and I just could not find my way out from the corporate world. I felt like if I couldn’t work in those places, then art was probably my creative outlet. I’ve always been an artist and I grew up in a family of artists. One of my grandma’s brothers was a photographer who had his own studio back in the 60’s. All of my aunts sew and create art themselves currently and always have. My mom was a seamstress at the former Cohen’s that was downtown across the street from what is now the Peoria Art Guild and she used to paint in high school; I have this beautiful self-portrait she did when she was a Junior in high school. My Pops utilizes his graphic design skills for his business. So much of my family is also musically talented. It’s literally in my blood, so I might as well just go for it and be an artist. Not only that but to be a collaborator, too. I like to work with other people and talk to other people about their life–and I really feel you can’t do that when working for those corporations and putting on a facade for them. That’s how I found what my true calling was–because fuck capitalism, fuck colonialism, and fuck imperialism.

TH: Say it with your full chest!

EM: [laughs] Art is the best way towards revolution.

BP: I always drew with my siblings. I barely spoke when I was a kid, and all through high school really. I also struggled academically. I’m dyslexic but I’m also narcoleptic–I would fall asleep in every single class, every single day and there wasn’t any helping it. Drawing in my notebooks always kept me a little more present though. When I went to community college and was deciding what to major in, I realized that when I do something physically it keeps me awake, whereas sitting through a class I’ll fall asleep regardless. I didn’t know I was narcoleptic at that time, but I knew art classes would keep me awake. I originally wanted to go into writing or film but I knew I would fall asleep in any other classes.

I’m also not as good at expressing myself verbally. Now I can do it a little bit more. But I have to make with my hands. I think [the typical format of] school is not made for everyone.

AM: My mom was going to college as I was growing up and she was studying oral communication and theater. She would take us to plays all the time–ones that happened at her school. She would practice her stage make up on us at home because she wasn’t living in a dorm setting, she was coming home to three kids. She always encouraged creativity. I think it was the teacher in her and her creative spark. I have early memories of my sister and me drawing on that old copy machine paper with the tear-off edges. Or watching cartoons with my brother who is ten years older than me. I loved those created worlds. As I got older, imagining these worlds, these heroes, and these characters gave me a place to fit in [within] my headspace. There aren’t a lot of Black people where I’m from, and my family is mostly white. I knew I was different, without [knowing exactly that I was a queer person], but by three years old I knew there was something going on. So a lot of my life had to be performative because of the microaggressions I would face in mostly white, straight spaces. The best way to survive it was to make these created worlds.

I always liked my art classes. I met all of my best friends through music and art–I was in band and theater classes. So, these imaginative spaces, worlds, and characters I made allowed me to daydream, and if I didn’t get them out they would just cloud my head. Art is how I got it out.

In middle school when we had to pick a career–which I don’t know why they were asking 11 year olds what they want to do with the rest of their lives–I would say I want to be a marine biologist or a doctor, but really I just enjoyed drawing all the things in those books. Then I realized that maybe I wanted to be a videogame designer. In high school, my goals became music and art. Then, when I got to college, the music department felt like such a colonized space–like the jazz department was completely white and academic. I was coming from [being a band kid] and that was a space to be weird, honk loudly on my horn, and run around in a uniform. It was a weird space, so to see it colonized [turned me off]. But in the art department I was seeing more freedom, all these wildly dressed people and cool paintings. I liked the community. So I ended up doing an art major. I realized that art is the universal catch-all that would let me do everything. I fell in love with language and linguistics. I studied Japanese. I fell in love with performance, weird sciences, and physics. I don’t want to be an expert in those spaces, but I can get obsessed with them and put it into my artwork.

Now, as an adult (I guess), I can use art to make sense of everything, to make sense of the experiences I had growing up and the in-between spaces I exist in–and share that with people. No one will know exactly what each piece of mine is about but you can tell when someone puts emotion into something. There’s a resonance and a connection. It’s how I fight my way to being in a space, and being seen and heard in my truth.

TH: What’s in the well of influence and inspiration for your work and practice? Who and what are some of your points of reference?

BP: What Alexander was talking about when it comes to creating worlds–I think that’s what got me started, especially when I was a kid. I think I got discouraged against that in college, though…

TH: But why?

BP: Teacher wise, I noticed that my teachers–painting teachers–encouraged a kind of masculinity in paintings. Whenever I would do something more illustrative, ones where I’m creating worlds and beautiful places, or paintings that tell a story, rather, it was often discouraged.

AM: People in academia love trauma.

BP: Yes! I am most inspired by nature and I had to get over the idea of that being cheesy. Even just painting in bright colors and wanting to paint a beautiful world was discouraged by academics in college.

TH: Which is really interesting because over the past year within the movements that are continuing to swell, there’s a growing, resounding, and repeated call for world-making and creating a world that imagines something different from and counters the violence of the world we currently live in. Understanding our relationship to the land and environment as Black people is the growing conversation. World-building in the face of all the things and systems that are working to take us down, and how capitalism is interwoven within all of this–a design that doesn’t fully encourage you to imagine, create, or daydream new worlds then bring them to existence–that is the current conversation. I’m always curious about what makes those spaces–of capitalism and academia–feel so threatened by creative energy and world-making. I appreciate you saying that.

EM: When I think of nature, I think of beauty. When you go outside and see nature, there’s a lot of color. And that brings us joy–being outside and enjoying the natural environment that has existed way before us. These educational institutions and the businesses they thrive off of want to tell us that this beauty doesn’t mean anything. But [they tell you that] getting a job as a graphic designer at a company that exploits you for your talent is where they want you to be. And that [kind of situation] limits people’s creativity.

I remember there was a painting teacher at community college who would require us to recreate classical art pieces.

AM: You have to recreate the “master work…”

BP: That’s not what I got at all! I’m not a terribly feminine person, but I definitely noticed in art classes–most of which were taught by men–I tended to think of creation, nature, and using brighter colors as feminine. It didn’t fly with those teachers–they didn’t like things to be [too feminine]. That was definitely something I had to get over after college.

The first time I showed works to [people I knew in college] after I left college, I was asked, “aren’t you concerned that people will think you can’t paint?” because my paintings were bright, beautiful, and illustrative. I was embarrassed about it being girly.

I think my teachers wanted me to always focus on the edgy, dully dark, and unfinished ideas that were filled with trauma and death, thinking that was deeper and more meaningful. Looking back, though I made some good marks, those paintings are lifeless to me.

One of the last paintings I created in my last painting class in college actually was the first painting that strayed from [the aesthetic preferences of my teachers] and it won first place painting at the annual juried show at [the school] that year. It’s an image of a dead deer I had found on the side of the road, but it was beautiful and full of color, painted in a careful, loving manner. It was death but it wasn’t grotesque at all. I think that overall the masculine-led interest in death by both teachers and fellow students was almost disrespectful and performative, which I guess is [part of] “toxic” masculinity.

Sometimes I view the bringing of death as part of earth’s more masculine traits, and the bringing of life as more feminine. And I admit I tend to view nurturing and healing as more feminine traits. But both are part of the circle that all humans, regardless of gender, participate in.

Also, from my experience with men in the arts, they are often obsessed with the problem, and art being about the question, so I tend to see hope and solution-focused art as feminine. And that may not be fully right, but it’s how I tend to think of the world. Maybe it was too much of how I was taught or pushed to view the world as well. Maybe masculine isn’t the right word–maybe just more “trauma-focused,” “performatively grotesque,” or “problem/question-focused” kind of art? That’s what was more often pushed by men.

EM: That’s a problem I have with art classes in general. There’s a predetermined definition of what art is. And art really shouldn’t have a concrete definition. Art is whatever the creator puts out. It’s so subjective. Brenda, when you’re saying that your classes taught more masculine pieces, that’s absurd.

AM: When you’re in academia, the people that go through it are often in the mindset of when you’re creative you should be encouraged to speak your mind. But at the same time, they come from the school of, “well, I learned it this way so this is how you should do it, too.” I remember in undergrad, I started making minimum, crisp, and performative work, even though I like messy, grossness, and crust. But I was trying to mimic all these people I was looking at in classes, and in grad school we had to write entire papers on our historical references. Knowing your [academic] context is important, and what’s around you or where you came from. But that shouldn’t be the only emphasis of your work. At the time I was influenced by artists like Ed Ruscha. But then, I saw Basquiat and was envious of how chaotic his work was [within the mainstream art world].

Now, my influences include a drag queen that I love who does sculpture and chaotic performances. I love video games, comics, and literature. Yes, there are artists I look at, but I’ve completely removed that [academic master artists] mentality. I look for work that is visually tasty and pulls me in–and I want to make work like the work that makes me feel that way. When I see work I like, I feel it in my jaw. I can almost taste it. I had to unlearn putting limits on the artists I’m looking at and feeling the need to cover my work in a ton of research [and academic references]. I just want to make a mess and have a good time doing it.

I just made a 3 minute video of me lip syncing to Japanese lyrics of a cartoon that I watch. It was the most fun I’ve had in forever, cackling to myself because no one knows what’s going on in the piece but me. In school they would have asked, “but why are you doing this piece?” I know the why, but for me the why is more of a conversation and not an elevator speech.

BP: Can’t art just be about bringing forward the world that you want?

AM: Art is the answer to a question that we don’t know.

BP: It can be part of the solution, it doesn’t have to even be the question.

EM: And it doesn’t always have to have an answer either. From what you said, Alex, about making a mess, that’s a huge part of my influence as well. Like the Japanese term wabi-sabi, which looks at the beauty of destruction, natural decay, and imperfection. In academia they teach us to [strive for] perfection and this world is far from perfect. I like the challenge of imperfectionism and destroying things on purpose and not making it look pretty because people expect art to be pretty. This is why I was greatly opposed to painting classical paintings because everything is so perfectly put together in the painting–I don’t want that.

Another huge inspiration of mine is skulls. I love them because of my dad–he loves them too, and he always talks about how people attribute skulls to death, but it actually should be attributed to life because the skull houses one of the most sensitive and crucial parts of your body–your brain–which gives you consciousness and allows you to sense the world around you. Skulls are a huge thing for me because it houses our existence. And death is a part of life.

TH: What you’re saying about skulls reminds me of the ways that skulls show up as a representation and celebration of life throughout so many cultures. Of course one of the first that comes to mind is Día de los Muertos. What you’re saying also reminds me of why Sixty was created, which was out of all of the frustrations that you’re expressing. We saw the way that all of these references and methodologies were being imposed upon us, even when they clearly did not fit. All the while our own references, which were often fundamentally different in intentions, origins, and processes, weren’t welcomed, given space, or valued in academia. We were also frustrated at the ways we were told to believe that the only important arbiters and bearers of culture are straight white men–not everyone is a straight white man!

AM: [laughs] Can that be the title of the interview? “Not everyone is a straight white man…”

TH: I’m coming at things from an art history standpoint, so my classroom space wasn’t the studio space where artists were creating. In the art historical space, which is a space that I realize has some overlap in the studio space, there’s so much implied in what and who we’re taught. A lot of art history, for me, appeared to ask that you take a step back from the world and visual culture in order to analyze it. I don’t want to call it a privilege, because it’s not like other folks outside of mainstream art historical canons don’t do it, but I’ve always felt like the history that has been taught to us had an air of luxury and privilege involved in it. These theorists were often able to keep the world at arms length and analyze and over analyze it rather than be in it and experience it within the body. That body knowledge and experiential knowledge isn’t often prioritized. Instead of learning techniques and then deciding for yourself what your citations and references are, which could be anything, you’re expected to take in the ‘masters’ and use them as your jumping off point, when in fact your jumping off point might be completely different.

AM: How can you walk into a classroom, especially one full of artists of color, and say, “we’re going to paint a master work today! And let me tell you about these masters: they are all white, they are all European, and they are all men.” How many women or Black works have been recreated? Why do they lump the entire continents of Asia and Africa together?

I’ve seen so many people get burnt out. And I’ve also met people who are enthralled with the academic art world, but have a punk attitude about it, believing it’s all a scam but still participating in it and still fitting into their system. You have to make a new way. People are afraid to be wrong and mess up, but you can release that pressure! No one will come after you for it. It’s perfectly fine to not know everything.

In the art history classes I’ve taught, I’ve always [been willing to admit] when I don’t know the answer. When a student asks a question about an artist, I’ll say I have no idea and pull up G*ogle. I found that students then are less afraid to ask more honest questions [when I show that I, too, don’t know everything].

Even teaching American art history, I would tell my students that we have to talk about colonial paintings. I would say, “I hate it, you’re probably going to hate it, but I’m going to try and make it as exciting as possible. But the only reason we’re going to talk about this is so that you have context for when we get to the juicy stuff later in the class. Just know that I’m as bored teaching it as you are listening to it…”

No one usually has those conversations with students saying that history and context are important, but sometimes it sucks and it doesn’t look like you most of the time. Just be honest and be vulnerable! What is it that Ms. Frizzle [from Magic School Bus] says? “…take chances, make mistakes, and get messy!”

TH: Why weren’t you my art history teacher?! I probably would have cried tears of joy if someone said that at the start of some of my art history classes. I want to bring the conversation into the present moment and ask you all about how the past year or so has impacted you and your practice.

EM: It’s been the most enlightening thing ever for me, as strange as that might sound. This ties into my existential beliefs; I’ve always thought that without purpose, everything is meaningless. This past year proved that. With the pandemic happening, businesses shutting down, and corporations making so much money off of the pandemic through our obsessions and addictions over materialistic goods just proved that every thing is kind of meaningless unless we [as people] give it an actual, meaningful purpose. So, when Brenda reached out to me about the Peoria Guild of Black Artists, that gave me purpose. It made me want to work and collaborate with other artists in order to express myself to the fullest extent possible. At this point, I think we’re still at a low point (*cough* late-stage capitalism *cough*) in this country or kingdom–whatever the fuck you want to call it. I’m now at a point where nothing can stop me. We’re able to use our art as a form of revolution against a world that tries to push materialistic things, and to, as artists, show how connection and relationships to one another and nature are so important–more important than the newest iPhone or latest car that’s come out. Art can show those connections. That’s the biggest thing that has come out of the past year for me.

AM: I always feel kind of guilty saying this because of the trauma everyone has faced over the past year, but this past year was a time of immense growth and thriving for me. I think, as a community we are always faced with trauma and we adjust to it. When people [who aren’t part of our communities] hear that, they will say, “my life’s hard too!” I’m not saying that other people’s lives aren’t hard, but my life shouldn’t be hard just because of how I look or how I express myself.

But I’m also happy and unbothered.

Yes, it’s scary. I’m always afraid that I or people I love could get shot by police. I’m afraid of being murdered for expressing myself. I get nervous on dates because I’m worried about a person hurting me. But also, I walked outside the other day while it was raining and walked past the lilac bushes and the smell of warm spring rain and lilacs made my serotonin explode and had me thinking, “this is why I’m alive–to smell these flowers!” I find joy everyday. And while the pandemic disproportionately affected [Black and trans people], I also feel like more people are experiencing what we go through. The past year has also given me space to grieve loss that I’ve suffered. Instead of being in survival mode, I had time to sit at home and process that–the universe told me, “you need to cry now, honey. You need to feel it and not just put it off.” I ended up doing a lot artistically, but it wasn’t always just about getting in the studio and making work. I also spent a month just playing Animal Crossing and not leaving the house. I was drinking wine and baking. I was just at home trying to rest. And that rest was exactly what I needed to have the momentum to do things like this.

And seeing people finally pay attention to the plight of people of color and the LGBTQ+ community and acknowledge it made us realize that we should strike while the iron is hot because people are paying attention. We have to make a space for us because no one else is. And since people are paying more attention now, maybe we will get the resources to make this space happen.

Emotionally, it was a hard year and we will be unpacking this for a long time. But growth, creativity, community, and collaboration-wise, it was amazing. I no longer have any tolerance for not being seen, even though in the Black community there is a lot of machismo, homophobia, and transphobia. I can’t expand my bubble when it’s not safe, but now I’m around people who see me in my truth and are nurturing. Now, I’m worried about coming off as mean or self-centered in spaces because I have the confidence to demand that I not settle or tolerate people who aren’t there to celebrate me. I’m not very agro (aggressive) and I’m not a fan of confrontation, but now I’ll leave or shut something down because when I’m able to be in a community like [PGOBA], why would I settle for anything less? We only need someone’s living room in order to start something like this. The past year has taught me about the importance of the spaces we make.

EM: Community is everything. Relationships with people are everything, truly.

BP: I feel like I hear more talk about capitalism now. And the best we have to combat that is community and forming communities that support one another. The more we isolate ourselves, the more dependent we are on the time and money we don’t have.

This year, all the shit that’s been going down has been here [before the pandemic happened]. Before the pandemic I was depressed and isolated. I hadn’t seen much of anyone. I was also dealing with immobility–I have a bad foot. At the beginning of 2020 I ended a relationship of seven years, couldn’t walk very well, and had to leave my job. I wasn’t making art. Then, as certain issues were getting much more attention and white people started noticing more of what was happening [to Black people], some people started randomly reaching out to apologize.

TH: You too?!

EM: I had a neighbor reach out to apologize.

AM: People from high school reached out to me saying, “I didn’t know [this was happening to Black people]…”

BP: I had spent so much time [in the past] arguing with some of these people, and suddenly they were reaching out saying, “Sorry I didn’t listen. I want to hear more from you.”

TH: The labor of it all–essentially reaching out to ask you to do work to help them do better.

BP: I’ve been becoming more vocal. We got asked to paint a Black Lives Matter mural without payment…

AM: “…for exposure, to honor your community…”

EM: “…in February…”

[All laugh]

BP: I think I’m just done with [those kinds of asks]. At a time when people are asking us to educate them, it felt so much better to just get together with a group of Black artists and not have these arguments and discussions. To not have to argue about our humanity. Forming a supportive community that is on my same page helped me begin to focus on the things I want to see in the world. By creating a space that focuses on supporting each other and making sure we’re all okay, and a space where we can focus on our growth and joy–I think that’s extremely important. I’m focusing on how to take care of each other and be there for each other.

AM: We’ve been burned by the art world. We’re applying for nonprofit status to support our reclusive community and because we’re doing things that other organizations [in Peoria] don’t do. We have private quiet practices that [counter] the barriers that the ‘professional’ art world creates. We try to create a space that is [non-hierarchical] and based on people’s strengths.

BP: We don’t have experience in this being our profession. We focus on early-career artists and we’re all learning this together. We share knowledge, skill sets, and resources…

EM: All of us have different expertise in different things. We can all learn from each other and absorb information from each other–not just as artists but also from working with other nonprofit organizations and doing community work in general.

AM: Together, it’s also easier to protect ourselves and gaslight-proof ourselves. As someone who doesn’t like conflict, I never realized how much I hold back on a lot of things. And as someone who grew up in a white family and surrounded by white people, there’s a lot [that I’ve held in]. But now I have a supportive Black community and the floodgates have been opened! We’ll close our meetings but then it will keep going for like three more hours because as a group we can talk about [these issues]. We validate each other. We listen. We’re safe.

TH: I want to go back to something that you said, Brenda, about forming the Guild. I’m sometimes reminded that for some non-Black folks there’s a false sense that when Black people get together in private spaces and are in community with one another, all we talk about is how the world treats us as it relates to our Blackness. And we don’t talk about or think about so many other things. That may be a little extreme, but I’m curious about what PGOBA provides each of you when you know there’s a shared understanding of the Black experience that can remain unspoken? Does that open up the opportunity to have different conversations among one another that aren’t always possible when you’re in mixed company in the art world and have to frontload your work and your conversations with an education on Blackness or the Black experience?

BP: Alex and I were just talking about how when two of us are in shows, it’s usually about Black history or being a woman of color. That’s when people want us, when it’s about being Black. As an artist, I focus a lot on portraiture–a lot of us focus on portraiture–because we didn’t see a lot of that growing up. We want to see Black faces in art. But being in a group of Black artists we don’t have to focus on being Black. I can think about painting landscapes. I love painting nature. For the [show at Illinois State University’s Gallery] I made a painting of a bird. [laughs] I don’t have to just paint portraits of Black people to ensure we’re represented. We’re all here.

When Alex sent in a bio for [the ISU exhibition] about being a Black artist, I said we don’t have to use that [version that focuses on their race]. We all have different interests and parts of ourselves that we can focus on instead of just trying to represent. We can explore all the different parts of ourselves.

EM: Even at our last general meeting, we had a huge conversation about anime. For the longest time growing up I thought only white people [and Japanese people] watched anime! Then, I was with this group of Black folx [who also love anime]. And even celebrities–like Thundercat dressing up as an anime character. Black culture is real tight with anime! Also, things that are considered ‘white.’ I love listening to punk music. And other members also love listening to things that are outside of what is considered ‘Black music.’ They listen to traditional Japanese music, classical, or country music. It’s nice to hear one another talk about stuff we like that’s considered white but has a Black history. We’re tight with all of these different mediums [and genres].

AM: For being a Guild of Black Artists, we really don’t talk about being Black that much. We talk more about making and doing.

EM: We already know what we go through. We live it. We hear from each other all the time. So, we just talk about things that we love to do.

AM: Like Brenda was saying, I’m so used to applying to mostly white spaces that my bio or statement has to give them context because I don’t want them to misinterpret my work. But I don’t have to add that context to this group.

BP: Even queerness.

AM: We had a conversation that was facilitated by a filmmaker in our group who is a cisgender, straight, Black woman. We were talking about a friend who was having issues coming out to their parents. [From that came] a whole conversation about the shared trauma of being queer, and members of the group who aren’t queer were saying, “I didn’t know you had it like that growing up…” But in having this conversation, facilitated by someone who didn’t have that experience, we felt genuine support and curiosity. It’s not scary to talk about these things [with them]. It doesn’t feel colonizing. It feels like it’s out of respect and wanting to get to know one another more. Our space is nothing like ones I’ve seen and experienced in the art world.

At any given moment there’s so much to talk about and to do.

TH: Brenda, it sounds like you are the initiator and instigator of the Guild. What was the origin story?

AM: Brenda is one of the most radical out of all of us but also the most soft spoken. She has tried multiple times and has always wanted to facilitate space for Black creatives. She’s always the one saying let’s get a show outside of Black history month. She’s always the one reaching out and doing work–like writing and archiving Black creativity in Peoria.

Then, I am good at talking to people and making folks outside of our community feel comfortable. I use my palatable Black privilege to talk to folks outside of our communities. [laughs] Through my work with Project 1612, I became used to knowing that if we wanted to see something happen then we would just need to do it [ourselves].

Brenda had this spark, and then I’m just loud! So we took Brenda’s vision–her nurturing the arts, her being involved in ceramics, and her desire for [an arts] family that supported one another–and said let’s do it.

BP: I have tried to organize things in the past. Sometimes everyone left, and sometimes I have an idea and tell that to one person, but then I get in a big group of people and don’t want to say anything because I get nervous. But then Alex and I met. We talked for a long time about what we wanted–with Quinton, too. We contacted everyone and then once we were all in a room together, I suddenly got nervous at the idea of explaining. Once everyone was there, I couldn’t say anything and that’s when Alex just took over and I was so relieved. [laughs]

AM: I really like communication and accessibility. With teaching, I feel it’s always about trying to make things accessible. So, with Brenda, she has strong opinions, powerful ideas, and lots of energy but people don’t always see that. But I can translate that for her.

So, it was initially a meeting. We talked to Morgan [Mullen], a friend of ours who lives with Brenda. We made a list of people we wanted to contact and artists we wanted to reach out to, and people showed up. The first meeting we had was a big venting session, but we also talked about spirituality and ancestry, there was a lot of laughing. Then we posed on Brenda’s front porch and took a photo. Then we posted that photo saying, “Be ready Peoria, something is coming.” We also put a hashtag of #GuildofBlackArtists. It was just a social gathering, but after we posted that it put the fear of God in the Peoria community. People started messaging us wanting to know what the group was. Our friend Mae [Gilliland Wright] who works for Peoria Magazine reached out wanting to write an article for the magazine–even though we’d only literally just met in Brenda’s living room once. She’s a really awesome writer and wrote an article. That was our catalyst to make a website to tell people who we are and to provide resources for other Black artists and advocate for being paid for our work. When the article was released, people started reaching out. We’re right now reaching the end of these initial collaborations, which has been a lot more reactive. We did a whole lot. Now that we’re finishing those, we’ll start doing our own thing as a guild. It’s been a wildfire.

EM: We started from the jump. We were contacted by the Art Guild and we only had three weeks to create new pieces for an exhibit. That was rough. But we had one of the biggest openings they’ve had in a very long time.

I came into the Guild through a phone call from Brenda–and I hadn’t talked to her in years.

BP: I was gone!

EM: She called me for this opportunity to join a group of Black artists and I said I was down and ready for it. I was really excited and am still excited about it. We need this.

TH: I want to ask two questions together: How did you decide on the name Peoria Guild of Black artists? And now, as you start to close out on these external requests that have dictated your work since you first announced the group, and as you start to move out of that reactionary space, what do you want the Peoria Guild of Black Artists to be?

AM: The name was Brenda’s doing. Art school ruined me, so I originally said “Black Artists Collective.” She was like, “I don’t want it to be ‘collective.’”

BP: It’s definitely a collective, but I want to go beyond a collective. I want to go beyond my experience with collectives. A guild feels like something we don’t have.

TH: It sets a different tone, and I think it draws on a certain kind of artistic history.

AM: Also, in wanting to create worlds, I kept geeking out thinking about video games and books where guilds were kind of these collective societies with a secret ring and a secret handshake. It’s not just an organization, it’s a foundation that focuses on a certain skill. We envisioned using Brenda’s garage to train people in ceramics and share supplies with the community. We want to create a medieval guild. Morgan, who is a graphic designer [in the group] is working on a sigil rather than a logo. We want to create an insignia and make rings. [laughs] It’s nerdy and fun, but we feel powerful. Brenda wanted to emphasize Peoria because she sees the loss potential in people who leave here. She wants to show that there’s a lot of Black creatives here and there’s a community that supports that.

At first we were thinking “Peoria Black Artists Guild” but we didn’t like the acronym PBAG. [laughs] Then, someone suggested GBA, “Guild of Black Artists,” and we were going to do a GameBoy logo with that one. [laughs] We had a group text where Brenda suggested Peoria Guild of Black Artists and Morgan was like, “PGOBA!” And everyone was like, “Yea!”

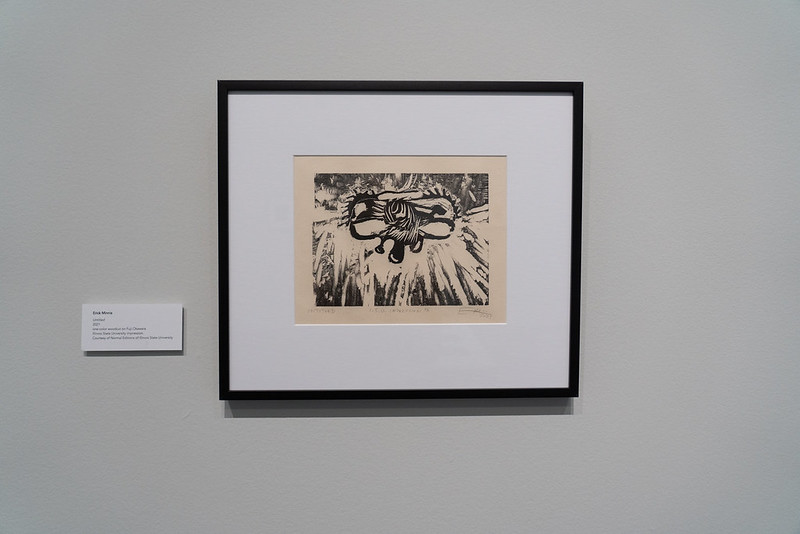

We do that shit a lot. For the ISU show we did a collaborative woodblock print with Normal Editions, and I jokingly said we should call it “New Kids on the Block” and Morgan went “That’s it!”

EM: And then Hannah [Offutt] said “Carving our Space.” And so we just put it together as “New Kids on the Block: Carving Our Space.”

AM: When everyone said, “That’s it!” I was like, “Really?!” And I told Morgan that she would have to be the one to email Normal Editions because I don’t think I could say it with a straight face. So she did, and now there’s a wall vinyl being printed with that title.

BP: To be fair, most of us had never done printmaking.

AM: I feel like a lot of folks of color have good intuition because we’ve been surviving and trying to live longer than this society wants us to. We plan, but we also [use our intuition]. We’re working together in our truth in a way that I’ve never done before.

BP: Going back to the question of where we’re going from here. A number of us were asked to do Black Lives Matter murals and they weren’t offering money [for us to do them]. Then, I was talking to Alex about people reaching out to Black artists when it looks good to do that. We started talking about how we need to make a list of demands…

TH: So there’s a PGOBA manifesto coming?

AM: Yea. So, we’re doing what we want to do in getting paid opportunities for artists. Like we’re doing a collaboration with Ameren–and finally seeing a big check come through for an artists’ work and time, and them being able to bill for their work and labor has set a standard. I almost cried when that first check from Ameren came through because it’s going to single Black mothers and young Black artists, and they’re being paid a living wage for their work. We really want to emphasize that. Now that things are opening up, we’re trying to hang out more. We want to make space for us to collaborate among the group and provide tools for the community. We also want to make our list of demands–something we release like the Guerilla Girls report card. We want to make a Black artists report card. So, if you want a rapport with our Black communities and Black creatives, here is what you need to do. Like, don’t come to us when it’s convenient. Make space for us. Or we will come to you.

BP: We’ve had a chance to say our piece to an organization or two.

AM: It feels good [to be able to set our own terms]. We’re not going to jump at every [offering of] money.

BP: We want to do projects that we can be proud of and where we can be creative.

AM: We’ll support community work, of course, but we’re also trying to get our artists paid. A lot of people are highlighting Black voices of high school students right now and a lot of it is unpaid. And we’re like, “No!” We’ve been colonized once, we’re not going through that again!

TH: We need to get people in the practice of mentioning dollars from the beginning.

BP: We don’t want anyone to be taken advantage of, so we band together [to keep that from happening].

AM: We will be doing our work always and anyways. If someone [outside of the group] wants to be part of that then they need to do these things. If things aren’t done in a certain way, we will pull out.

TH: That’s so important. And if there’s any time to do it, it’s now. Also, there are a lot of people who are worried about being on “the wrong side of history.” So, now is the time to ask for what you need. How many artists are in the Guild?

EM: I think about 18…

AM: We also have some at-large folks who are from Peoria but not here and want to be involved.

BP: And we’re going to get an application process started. We started during the pandemic, so we’re starting small.

AM: We’re also trying to make a solid and equitable foundation so that if any of us move or step away, it can sustain itself. We don’t want to see this momentum stop. It’s a lot of work but we don’t see anyone doing it, so it feels good.

BP: Administrative stuff is so out of my comfort zone. I hate emails.

TH: If you need an administrative shoulder to lean on, I’m here. At Sixty, that’s how we do it. We have a distributed leadership model and decentralize. I’m continually working to ensure that our survival doesn’t rely on one person. As a co-founder, it means releasing a lot of daily things and creating new internal pieces and processes.

EM: I’m also in the process of taking business classes, which I hope will help not only for the group, but also for any businesses we might want to start in the future. We talked a lot about starting up businesses–like a Black coffee shop or cafe. And we all agreed…

BP: With a gallery space!

AM: There are a few people who have their own businesses, and they can bring in some business and legal insight, which sounds like internet dial up noise to me! There’s a broad range of skill sets and talents.

TH: I love this. You’re talking about all of the things I’m interested in. And it’s wonderful to hear where you’re going. Once you open the flood gates, it becomes clear that all of these ideas and opportunities have been waiting there to be tapped. Now, I want to bring this conversation back to place. What does it mean for you to be doing this work in Peoria?

AM: I’m from a small town in West Virginia and I always imagined living in a densely populated area like Chicago or San Francisco. But Peoria is still a bigger city to me. It’s the size where there’s enough room to make things happen. A lot happens in this city. I fell in love with being here. I’m trying to get my family to move here. And I know that if I ever leave, this is where I will come back to for the holidays. Peoria has become important [to me]. I’m not a fan of metro-normativity. I want people to get out of the mindset that they have to go to [a big city] to be happy. You can make your happiness anywhere. Oppression and depression can be steeped in environment. And sometimes in a big city, your voice can get lost. Being in Peoria lets me increase the bubble of love and make it bigger. But then also, it lets me set a standard for other people. You can make a space for you and your community–it doesn’t matter if it’s here or in rural Nebraska. You can just meet one day in someone’s living room. You don’t have to follow the rules–like Marsha P. Johnson and William Dorsey Swann fought for our right to gather. It’s powerful. And I hope when people see the work that we’re doing here, they know that it can happen anywhere. Black people are everywhere. Black people are in West Virginia. We have Afro-Lachians!

TH: Yes, Afro-Lachians!

EM: Being born and raised here, I hated the city with a passion until about a year ago. I grew up in a failed school system. There’s the idea of having to make a living through the corporate world, and as a society we are told we need to move into bigger cities to achieve our goals. I tried to do that and I was miserable. That depression [and oppression] follows you wherever you go. I felt stuck. About seven years ago I realized living in a city that’s smaller is not so bad because you can have those connections with people and it helped me realize the importance of community. It’s important to be tied with people–and not just friends and family, but the people you see at the grocery store or on the street. Having those relationships is important, and in bigger cities sometimes those relationships are harder to come by.

Being Black and going through a school system that doesn’t focus on the arts was one of the reasons we formed the Guild, too. To show kids that they can make a career out of being an artist. You can be an artist, get paid for it, survive off of it, and still have fun with it. And instead of waiting for something to happen, just get out there and do it. Make something happen–especially in places where opportunities are limited. I’ve always been someone who has waited for something to happen; for a reason for me to be included because I felt like I didn’t belong. That has ended. I’ve waited too long and now I’m breaking down the door to create something and to force inclusion. Peoria has always been home and people need to realize that it’s home for the unheard.

BP: Peoria is my home and it is literally a place for roots. I’m a plant person. I have no desire to leave, to be honest. And I think Peoria is the right size. I can live near downtown and also there’s a river where there are bald eagles, herons, and beavers just a walk away. I wouldn’t necessarily want to live in a smaller or bigger town–Peoria is the size where you can build your space. If it wasn’t the goal for every millennial to leave Peoria, we could make a big difference in how the city is run and how things are done. Compared to bigger cities, it’s affordable–especially in the arts. There’s a chance to make a big difference. And you can also get some nature without being surrounded completely by white people.

Someday, I would love to move to the mountains, but right now, I’m here. I found myself here, so this is where I’m doing what I’m doing.

TH: My last question is a lovefest question. What is it that you appreciate about each other individually and as a collective?

EM: I love to have connections with people. I’m a spiritual person and I believe we’re all created from the universe and we harness that energy. Our energy levels differ from one another, but with PGOBA it’s on a whole different spectrum. I love our members like my own family. I call them my PGOBA Family.

AM: Once you get that ring on, you don’t leave!

EM: (to Brenda) I’ve known you since my first community college tenure in 2008 and you went to school with my older sister in elementary school. I’ve always had a connection with you as a family member. I love talking to you and hearing you talk. I love the calmness about you, but you also have the energy of fire! You embody the flames themselves and you create flames.

TH: Are these literal or metaphorical fires?

EM: Both! (to Brenda) You’re a dear sister to me, for sure. And you’re an amazing person.

And Alex, I’ve known you for a very short time but I have seen you around. I’m very aware of that. The first time I saw you was at the Richard Pryor statue revealing. You were butch Alex, in a butch phase at that time. I’d never talked to you. Then, ironically, the next time was a Black History Month show at what’s now Lit on Fire. And we have mutual friends who I would always see you with. We never spoke, though. And I always wanted to talk to you because you seemed like such a cool person. I always wanted to learn more about you. And now knowing you and having this connection, I absolutely love the energy that you bring and what you stand up for. And I always got your back if anyone tries to fuck with you–you too, Brenda! I got y’all. I may be cis, but I support my queer people. We all Black. I love you both very dearly.

AM: PGOBA is the Black family I never had. It’s the proof that I’m not crazy. It’s a community connection that’s letting me explore parts of myself that I didn’t even know I was repressing. There’s so much rooted in us as a community. Even growing up in white spaces, it was there. I couldn’t see it until I found people to share it with. It’s enriching and validating. It just feels so good.

Erick, you are such a good balance of the realistic understanding that being alive sucks sometimes. Not a cold perspective. Not the white male nihilistic view. It’s a realistic view that [acknowledges that] it can be painful to exist but then why not fill that space with love because we’re part of something bigger? You balance the fact that things are hard and won’t always be nice, but leading with love and community makes it worth surviving. I think you really embody that. We’re Black and wearing skulls, but we can geek out around video games and cute shit. You’re this perfect balance of ideals I have, the realness and pain of being alive as a person of color. But then you make it possible to experience the love.

Brenda, you have consistently, from the moment I met you, surprised me. You give off this aura. It’s true when you say you’re a plant person. I view you as a mother nature, literally working with plants but so connected to the environment. You give a vibe of nurturing and growth, and a comforting aura. I remember one of our first conversations at Broken Tree where we were talking about the ways that people try to prolong their lives–paying money to do all the crazy stuff to live longer. And Brenda said, “No, everyone is supposed to die. We shouldn’t go to outer space to [colonize] other planets. Once Earth’s time is up, it’s up.” And I was [stunned]. Now, getting to know her more, there’s a balance. I’m on the Leo side of the Leo/Cancer cusp, and she’s on the Cancer side of the Leo/Cancer cusp, so it’s our different proximities to water and fire. I am constantly surprised by Brenda. She’s one of the most heated, powerful, and strong people I’ve ever met, but no one would know that from your external demeanor–which has developed in a world where you have to survive. Even your texts and emails give a snippet [of that fire]. The anxiety and performance aspects are completely removed. Especially when you’re angry, I can feel the strength coming off of those messages. There’s so much life. You remind me of all the gods from Hindi beliefs who create and nurture life. And ones that act as warriors with so much passion. I’m always surprised by how deep your reservoir runs. I sometimes get mad when people don’t see that, and as our love grows. There’s so much there. I love that about you, and I love you.

BP: I wasn’t in a good place. And this definitely is a family. It’s a big motivator of my life right now and it helped to pull me out of a bad place–a pit of despair. I didn’t have much motivation to create on my own, so PGOBA helped me get back to my art. We’re working towards something together. This group is perfect.

Erick, I identify with you a lot. We’re both pretty reclusive and we both are always wearing black [laughs]. Erick and I have worked on putting together a photography studio, and we’ve known one another for a long time, but we hadn’t had extended one-on-one conversation. [When we did talk], it was so good. You add so much to everything you do. And you’ve got really cool style–you and your work. You’re great.

And Alex, you do so much. I don’t even understand how you do all you do. You give so much energy to things. Without your force, PGOBA would have never gone beyond [our conversation]. You speak, you make things happen with your voice and your energy. You also make people feel heard. To hear me is not an easy thing. And it’s not easy for me to speak to people. You’ve made it easier for me and I feel very safe to speak with you–that’s a power.

AM: Tempestt has this witchcraft in interviews that makes you leave so much of yourself [in the interview] every time!

EM: I’m feeling all of it right now!

BP: It’s true!

TH: I really appreciate that. I don’t get to do interviews very often but I love them. I want to thank you for being so generous with your time and your stories. I’m beyond inspired. The work you’re doing hits me pretty deep and has given me so much to think about when it comes to my own relationship with Peoria. So, I thank you.

Featured Image: Ten members of the Peoria Guild of Black Artists stand together outside on the front stairs of the home of artist and founding member Brenda Pagan. Photo by Erick Minnis.

Tempestt Hazel (far right) is a curator, writer, artist advocate, and co-founder of Sixty Inches From Center, pictured here with her niece, Simone, and mother, Sherry. Find more of her work at tempestthazel.com. Photo by Sherry Hazel.